JUMP TO

TRANSLATE

INTRODUCTION

Historian Paul Kennedy has called the emergence of the United States as a player on world stage the most decisive change in late 19th Century. America saw herself as exceptional and felt justified in projecting influence beyond her borders. Americans still intended to avoid “entangling alliances” that George Washington had warned against but felt free to be more actively involved in the affairs of the world.

America had always been driven by the idea of manifest destiny, which at first meant expansion over the whole continent of North America. With the ending of the frontier and the completion of the settlement from sea to shining sea, however, the impulse for further expansion spilled out over America’s borders. American isolationism began to change late in the century for a variety of reasons.

First, the industrial revolution had created challenges that required a broad reassessment of economic policies and conduct. The production of greater quantities of goods, the need for additional sources of raw materials and greater markets all called for America to look outward.

But did this have to happen? It’s true that money is a powerful motivator and American business leaders naturally wanted places to sell their products and find raw materials, but the same is true today and we do not need to invade China to buy and sell with the Chinese. Couldn’t the same have been true 120 years ago?

What do you think? Did America need to be an imperial nation?

AMERICAN EXCEPTIONALISM

American Exceptionalism is the theory that the United States is inherently different from other nations. In this view, American exceptionalism stems from its emergence from the American Revolution, becoming what political scientist Seymour Martin Lipset called “the first new nation” and developing a uniquely American ideology based on liberty, egalitarianism, individualism, and the rule of “We the People.” Although the term American Exceptionalism does not necessarily imply superiority, many Americans came to see the United States as exceptional and therefore better than those other countries who are not exceptional. To them, the Unite States is the City upon a Hill, a shining example for other nations.

During the late 1800s, industrialization caused American businessmen to seek new international markets in which to sell their goods. Additionally, the increasing influence of Social Darwinism led to the belief that the United States was inherently responsible for bringing concepts such as industry, democracy, and Christianity to less developed savage societies. The combination of these attitudes and other factors led the United States toward imperialism.

Pinpointing the actual beginning of American imperialism is difficult. Some historians suggest that it began with the writing of the Constitution. Historian Donald Meinig argues that the imperial behavior of the United States dates back to at least the Louisiana Purchase. He describes this event as an, “aggressive encroachment of one people upon the territory of another, resulting in the subjugation of that people to alien rule.” Here, he is referring to policies toward Native Americans, which he said were, “designed to remold them into a people more appropriately conformed to imperial desires.”

Whatever its origins, American imperialism experienced its pinnacle from the late 1800s through the years following World War II. During this Age of Imperialism, the United States exerted political, social, and economic control over countries such as Hawaii, Russia, the islands of Micronesia, the Philippines, Cuba, Spain, Germany, Japan and Korea.

ALASKA

America’s first real foray into acquiring territory outside of what we now call the contiguous United States was Alaska. Often overlooked, the purchase of Alaska from Russia marks the opening of America’s Imperialist Era.

Russia owned the territory of Alaska and had ventured down the western coast of North America as far as Northern California, where they built Fort Ross, a mere two hour’s drive north of San Francisco. Anticipating, however, that holding on to a distant territory on a different continent might be difficult and unprofitable, the Russians were in the mood to get rid of the territory and sent a German negotiator to meet with the United States. In 1867, Secretary of State William Seward purchased Alaska for $7.2 million, a venture which critics referred to as Seward’s Folly.

Only if gold were found, newspaper editors decried at the time, would the secretive purchase be justified. That is exactly what happened. Seward’s purchase added an enormous territory to the country, nearly 600,000 square miles, and gave the United States access to the rich mineral resources of the region, including the gold that triggered the Klondike Gold Rush at the close of the century, and later vast reserves of oil. As was the case elsewhere in the American borderlands, Alaska’s industrial development wreaked havoc on the region’s indigenous and Russian cultures. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline now carries millions of barrels of crude oil from wells in along the Arctic coast to ports in the South where it is loaded onto tanker ships and carried to refineries in California and elsewhere. This discovery of gold and oil have made Seward’s purchase of Alaska from Russia appear to be one of the wisest and best deals America ever concluded.

ECONOMIC IMPERIALISM

While the United States slowly pushed outward and sought to absorb the lands in the American West and the indigenous cultures that lived there, the country was also changing how it functioned. As a new industrial United States emerged in the 1870s, economic interests began to lead the country toward a more expansionist foreign policy. By forging new and stronger ties overseas, the United States could gain access to international markets for export, as well as better deals on the raw materials needed domestically.

The concerns raised by the economic depression of the early 1890s further convinced business owners that they needed to tap into new markets, even at the risk of foreign entanglements. Because of these growing economic pressures, American exports to other nations skyrocketed in the years following the Civil War, from $234 million in 1865 to $605 million in 1875. By 1898, on the eve of the new century, American exports had reached a height of $1.3 billion annually. Imports over the same period also increased substantially, from $238 million in 1865 to $616 million in 1898. Such an increased investment in overseas markets in turn strengthened Americans’ interest in foreign affairs.

At a time when business leaders such as Carnegie and Rockefeller had tremendous influence over political decisions, it is no surprise that politicians bent to the will of business.

RELIGIOUS IMPERIALISM

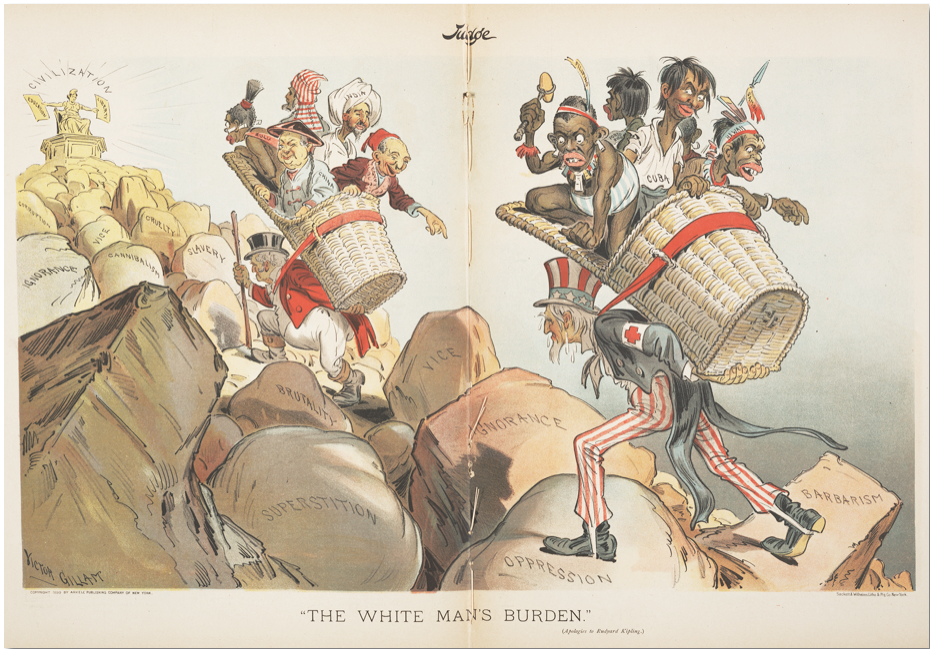

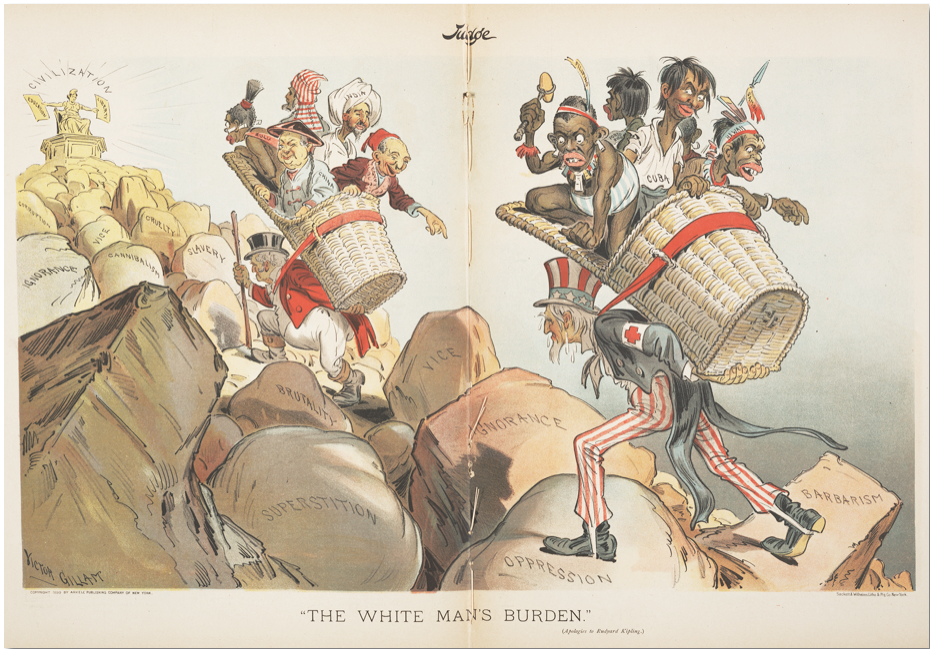

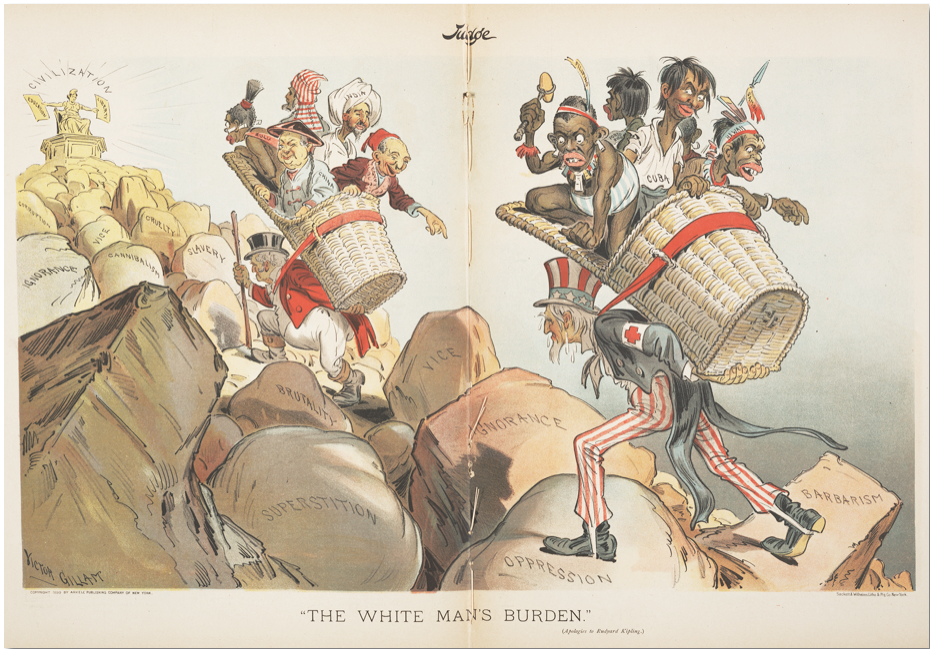

Businesses were not the only ones seeking to expand. Religious leaders and Progressive reformers joined businesses in the growing interest in American expansion, as both sought to increase the democratic and Christian influences of the United States abroad. Editors of magazines such as Harper’s Weekly supported an imperialistic stance as the democratic responsibility of the United States. Several Protestant faiths formed missionary societies in the years after the Civil War, seeking to expand their reach, particularly in Asia. Missionaries conflated Christian teaching with American virtues, and began to spread both gospels with zeal. This was particularly true among women missionaries, who composed over 60% of the overall missionary force. By 1870, missionaries abroad spent as much time advocating for the American version of a modern civilization as they did teaching the Bible. Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

Uncle Sam and John Bull, representing the United States and Great Britain, carry the people of their respective colonies toward civilization over rocks labeled “ignorance,” “oppression” and “superstition.” It is hard to image and more clear visualization of the racist idea of the White Man’s Burden.

THE WHITE MAN’S BURDEN

“The White Man’s Burden: The United States and the Philippine Islands”, an 1899 poem by the British poet Rudyard Kipling, invites the United States to assume colonial control of that country.

In the poem, Kipling, the acclaimed author of such classics as The Jungle Book, exhorts the reader to embark upon the enterprise of empire, yet gives somber warning about the costs involved nonetheless. Perhaps serious or perhaps satire, the poem describes the virtues of spreading Western Protestant Christian culture despite the financial and military costs incurred by the imperialist power. This, according to Kipling was the White Man’s Burden – that being superior implied the burden of teaching less civilized people. Clearly, it was a racist idea, but one held by many Europeans and Americans at the time.

EUROPEAN IMPERIALISM

Furthermore, even if Americans had reservations about expansionism, as many did, their doubts were often tempered by the fact that everybody seemed to be doing it. The late-1800s were a time of colonialism, when the European powers seemed bent on gobbling up all the underdeveloped areas of the world and turning them into colonies for military, commercial or political purposes. Europeans had divided Africa amongst themselves, without the consent of anyone in Africa. They were expanding into China. It was said that the sun never set on the British Empire since Britain controlled territory on every continent around the world.

Surely if the Europeans were doing it, many Americans figured, America could conquer foreign lands as well. Besides, if Britain, Italy, Germany or France got there first, Americans might be cut off from access to lucrative markets.

SEA POWER

Perhaps no one did more to promote the idea of empire than Alfred T. Mahan. Mahan was a former navy man and historian and in his 1890 book, The Influence of Seapower upon History, he suggested three strategies that would assist the United States in both constructing and maintaining an empire.

First, noting the sad state of the United States navy, he called for the government to build a stronger, more powerful version. Only a strong navy, he argued could protect American merchant ships as they plied the world’s oceans expanding American trade.

Second, he suggested establishing a network of naval bases to fuel this expanding fleet. This was vital, as the limited reach of steamships and their dependence on coal made naval coaling stations imperative for increasing the navy’s geographic reach.

Finally, Mahan urged the future construction of a canal across the isthmus of Central America, which would decrease by two-thirds the time and power required to move the new navy from the Pacific to the Atlantic oceans.

Overall, Mahan made a strong case for his thesis: great nations controlled distant territory to enrich the mother country and had strong navies to protect trade.

Heeding Mahan’s advice, the government moved quickly, passing the Naval Act of 1890, which set production levels for a new, modern fleet. By 1898, the government had succeeded in increasing the size of the navy to an active fleet of 160 vessels, of which 114 were newly built of steel. In addition, the fleet now included six battleships, compared to zero in the previous decade. As a naval power, the country catapulted to the third strongest in world rankings by military experts, trailing only Spain and Great Britain.

HAWAII

American interest in the Hawaiian Islands goes back to post-revolutionary days when American traders first started traversing the Pacific. Hawaii was a convenient stopping-off place for ships bound for China and Japan. American missionaries arrived in the islands in the early 19th Century. The scenery, climate and valuable crops like sugar and fruits attracted the attention of investors. In 1842, Secretary of State Daniel Webster recognized the importance of Hawaii for the United States. Native Hawaiians wanted to resist foreign intervention and saw the Americans as an ally in that effort. Although the United States made no move to annex or otherwise control Hawaii, American policy consistently sought to keep other nations from extending their influence over the islands. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Queen Liliuokalani, who gave up her throne peacefully rather than see bloodshed and then lobbied unsuccessfully for the United States to intervene to correct the injustice.

In 1875, the United States signed a reciprocity trade treaty with Hawaii that admitted Hawaiian sugar to the United States duty free. Under the terms of the treaty, no Hawaiian territory was to be disposed of to a third party. The Reciprocity Treaty was renewed in 1884, and in 1887, rights to a fortified naval base at Pearl Harbor were added to the agreement. Later that year a revolution of White, mostly American, planters forced Hawaiian King Kalakaua to create a constitutional government, which was dominated by minority White Americans. By 1890, American planters controlled two-thirds of the land in Hawaii.

The McKinley Tariff of 1890 ended the favorable sugar trade situation for Hawaii, resulting in large losses for American planters. Americans also lost power when Queen Liliuokalani, a strong Hawaiian nationalist, acceded to the throne in 1891 following the death of her brother, King Kalakaua. An educated woman, she claimed that “Hawaii is for the Hawaiians!” and opposed political reforms. In 1893, Sanford Dole, the son of an American missionary, formed a Committee of Safety to overthrow the native government. American Minister to Hawaii John L. Stevens violated international law by improperly ordering American Marines ashore from a warship, threatening the government. Dole became president of a new provisional government. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

US Marines in Honolulu helping to enforce the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy. The action was clearly a violation of international law and was reversed by the US government, but the damage had already been done.

An annexation treaty was hastily sent to Washington and then submitted to the Senate by President Harrison, but, recognizing the obvious illegality of the overthrow, Democrats in the Senate blocked it. When President Cleveland took office in March 1889, he withdrew the treaty and ordered an investigation. Cleveland sent former congressman James Blount to Hawaii. Blount reported wrongdoing against Queen Liliuokalani, and President Cleveland tried to have her restored to her throne. However, the provisional government refused to step down and Cleveland was unwilling to use force in the matter.

Despite opposition, annexing Hawaii fit well into Mahan’s plan for American expansion. The naval station at Pearl Harbor provided a critical stopping point in the middle of the Pacific and Hawaii’s plantations were the source of valuable agricultural products.

President McKinley negotiated a new annexation treaty, but it was blocked by anti-imperialists in the Senate, failing to get the necessary 2/3 vote. Congress then annexed Hawaii by a joint resolution of Congress, which required only a simple majority. President McKinley approved the resolution on July 7, and Hawaii became a United States territory on June 14, 1900.

THE PACIFIC

Hawaii was not the only Pacific Island to receive American attention. The United States also expanded its influences, most notably Samoa. The United States had similar strategic interests in the Samoan Islands as they did in Hawaii, most notably, access to the naval refueling station at Pago Pago where American merchant vessels as well as naval ships could take on food, fuel, and supplies.

Germany in particular showed a great commercial interest in the Samoan Islands, especially on the island of Upolu, where German firms monopolized copra and cocoa bean processing. Britain also sent troops to protect British business enterprise and access to Samoa’s harbors.

An eight-year civil war broke out, during which each of the three powers supplied arms, training and in some cases combat troops to the warring Samoan parties. The Samoan crisis came to a critical juncture in March 1889 when all three colonial contenders sent warships into Apia Harbor, and a larger-scale war seemed imminent. A massive storm damaged or destroyed the warships, ending the military conflict and giving the great powers a chance to find a diplomatic solution to their competing claims for Samoa.

The United States, Great Britain and Germany divided the island chain. The eastern island group was given to the United States and became American Samoa. The western islands, by far the greater landmass, became German Samoa. The United Kingdom gave up all its claims in Samoa and in return, Germany surrendered its claims to Tonga and the Solomon Islands.

After World War I German Samoa was granted independence, but American Samoa remains a territory of the United States.

OPPOSITION TO IMPERIALISM

Not everyone in the nation was happy with America’s new possessions. The Platform of the Anti-Imperialist League of October 17, 1899, opened as follows:

“We hold that the policy known as imperialism is hostile to liberty and tends toward militarism, an evil from which it has been our glory to be free. We regret that it has become necessary in the land of Washington and Lincoln to reaffirm that all men, of whatever race or color, are entitled to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. We maintain that governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed. We insist that the subjugation of any people is ‘criminal aggression’ and open disloyalty to the distinctive principles of our Government.”

The moral costs of creating an empire were not lost on many Americans. The American Anti-Imperialist League was an organization established in the United States on June 15, 1898, to battle the American annexation of the Philippines. The League also argued that America’s war with Spain in 1898 was a war of imperialism under the guise of a war of liberation.

The anti-imperialists opposed expansion because they believed imperialism violated the credo of republicanism, especially the need for “consent of the governed.” They did not oppose expansion on commercial, constitutional, religious, or humanitarian grounds, rather, they believed that the annexation and administration of third-world tropical areas would mean the abandonment of American ideals of self-government and isolation—ideals expressed in the United States Declaration of Independence.

The Anti-Imperialist League represented an older generation and was rooted in an earlier era. In the end, they lost their campaign to win over public opinion and in the 1900 election President McKinley and imperialists in Congress won by wide margins.

CONCLUSION

America became an imperial nation for many reasons. There were business interests, military interests, racist cultural interests, and sometimes simply the motivation of not losing out to European rivals. However, did this have to happen? American business relationships thrive today with nations that are fully independent. Americans maintain friendly relationships with governments who welcome American military personnel and host our military bases on their soil. American culture has been widely adopted in many places. In fact, it is hard to find a place on earth were one cannot buy Coca-Cola.

Certainly the present is an argument that the Imperialist Era was a mistake – a time when Americans succumbed to our most racist, greedy tendencies that were contrary to our founding ideals.

What do you think? Did America have to be an imperial nation?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: American leaders sought to expand and become an imperial nation for a variety of reasons, but most significantly to have access to natural resources and markets. There were some critics of imperialism.

Americans have believed for a long time that we are exceptional in the world. This idea has led American leaders to involve ourselves in other countries. Sometimes we think we can fix problems or can teach other people the best way to live or run their government. This idea might go as far back as the Pilgrims who believed that their success as a colony in the 1600s was because they had a special covenant with God.

The most common reason Americans took control of distant lands was to make money. Sometimes they were looking for raw materials. Sometimes they wanted to have access to markets with people who would buy American-made goods.

Sometimes imperialism was motivated by religion. Christian missionaries in the United States travelled abroad to spread their beliefs. Usually they looked down on the beliefs and traditions of the people they met. Hawaii is one example where this was true.

Other Americans (and Europeans) believed that their culture was superior to all others, and it was their responsibility to share their way of life with the lesser people of the world. This idea was nicknamed the White Man’s Burden. Clearly, it is based on racism.

An important reason politicians became interested in taking control of territory was to provide ports for the navy to stop and refuel their ships. The author Alfred Mahan argued that great nations need colonies and navies to protect trade. Theodore Roosevelt believed in this idea. Hawaii, Guam and the Philippines all had good harbors.

The United States began taking control of territory outside of the contiguous 48 states in 1867 when we purchased Alaska. Later in the 1890s we took control of more territory by annexing Hawaii and Samoa. The European nations also were involved in imperialism at this time in both Asia and Africa.

Not all Americans liked imperialism. Some believed it was bad to take land that belonged to other people. Some thought it was too expensive. Still others did not like the thought of foreign people moving to the United States after their homes became American territories.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Alfred T. Mahan: Author of the book “The Influence of Seapower upon History.”

Queen Liliuokalani: Last queen of the independent Kingdom of Hawaii.

American Anti-Imperialist League: Organization of Americans opposed to imperialism.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

American Exceptionalism: The idea that the United States is unique in the world, usually in the sense that the United States is better than all other nations due to our history and form of government.

City Upon a Hill: An image borrowed from the Bible by Puritan minister John Winthrop to describe the United States as a model society that the rest of the world should look up to as an example.

Social Darwinism: The idea that people, businesses and nations operate by Charles Darwin’s survival of the fittest principle. That is, successful nations are successful because they are inherently better than others. At the turn of the century, White culture was seen as superior to others because Europeans and the United States were imperial nations and had defeated the people of their colonies.

White Man’s Burden: The idea that White Americans and Europeans had an obligation to teach the people of the rest of the world how to be civilized.

![]()

BOOKS

The Influence of Seapower upon History: Book by Alfred T. Mahan in which he argued that great nations have colonies and navies to protect trade with those colonies. This book inspired Theodore Roosevelt and led to the acquisition of overseas colonies such as Hawaii, the Philippines, Guam and Samoa.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Contiguous United States: The 48 states that touch. In other words, all the states except Alaska and Hawaii.

Pearl Harbor: Naval base on Oahu in Hawaii. The United States annexed Hawaii in part to gain control over this important coaling station.

American Samoa: Island group in the Pacific annexed by the United States. It was divided with Germany and remains an American territory.

![]()

EVENTS

Seward’s Folly: A nickname for the purchase of Alaska, alluding to the idea that it was a mistake.

Annexation of Hawaii: June 14, 1900 resolution by Congress that made Hawaii a territory of the United States.