INTRODUCTION

The African American bid for full citizenship was surely the most visible of the battles for civil rights that took place in the post-war decades. However, other minority groups that had been legally discriminated against or otherwise denied access to economic and educational opportunities began to increase efforts to secure their rights as well. Mexican Americans, Native Americans, disabled Americans, and homosexual Americans all sought ways to improve their lives and win justice and respect.

Like the African American Civil Rights Movement in the South, some of these movements featured charismatic leaders, marches, legal victories, and captivating protests. Some were violent, while others embraced nonviolence. Some were successful, while others faced setbacks and ended with dreams unfulfilled.

In the end, we can look at these movements as a group and consider what factors made them similar and different, and in a larger sense, why some succeeded while others faltered.

What do you think? What makes a movement successful?

THE MEXICAN AMERICAN FIGHT FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

Like the African American movement, the Mexican American civil rights movement won its earliest victories in the federal courts. In 1947, in Mendez v. Westminster, the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that segregating students of Hispanic descent was unconstitutional. In 1954, the same year as Brown v. Board of Education, Mexican Americans prevailed in Hernandez v. Texas, when the Supreme Court extended the protections of the Fourteenth Amendment to all ethnic groups in the United States.

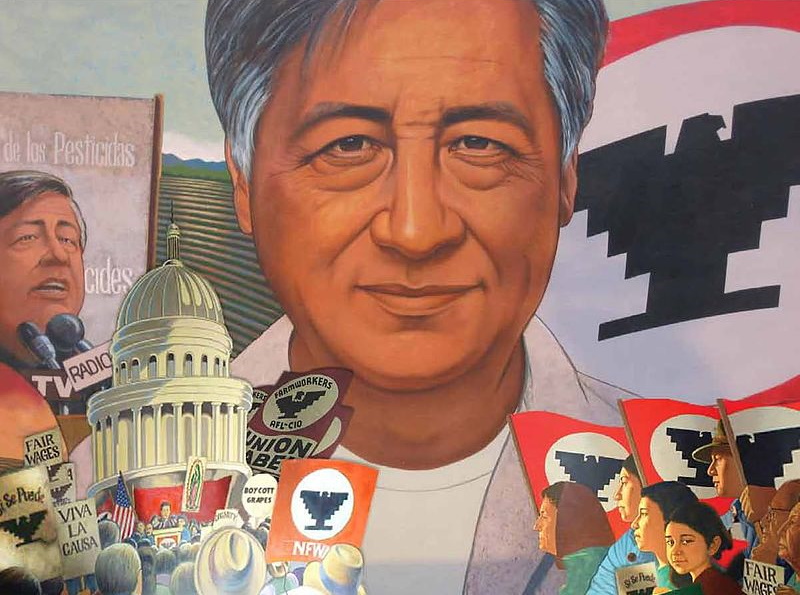

The highest profile struggle of the Mexican American civil rights movement was the fight that Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta waged in the fields of California to organize migrant farmworkers. In 1962, Chavez and Huerta founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA). In 1965, Filipino grape pickers led by Filipino American Larry Itliong went on strike to call attention to mistreatment of farmworkers in California’s Central Valley. The Filipino Americans and Mexican Americans who picked the nation’s food worked for tiny wages, had no health care, could not send their children to school, and endured humiliating working conditions. In many cases, there were no bathrooms and men, women and children had no choice but to relieve themselves in front of the other workers in the fields. Secondary Source: Mural

Secondary Source: Mural

A mural depicting Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers black eagle logo, as well as the marches and farmworkers he led.

Chavez, Huerta and the Mexican American farmworkers voted to join the strike and the two organizations merged to form the United Farm Workers. The farm workers under Chavez’s leadership used many of the same tactics that the African American protesters were using in the South. In 1966, they embarked on a 300-mile pilgrimage from Delano, California to the state’s capital of Sacramento in an attempt to pressure the growers and the state government to answer the demands of the Mexican American and Filipino American farm workers. The pilgrimage brought widespread public attention to the farm worker’s cause. The farmworkers also gained the support of the powerful AFL-CIO union.

However, despite the ongoing strike by the farmworkers, it was ultimately a boycott of California grapes that made the difference. Farmworkers convinced many Americans to stop buying grapes grown in California and grape sales dropped year after year. The Delano Grape Strike and Boycott finally ended in 1970 when California growers recognized the right of farmworkers to unionize. The farmworkers had been on strike for eight years. Most had lost everything, but felt that it had been worth it to regain a sense of human dignity.

The equivalent of the Black Power movement among Mexican Americans was the Chicano Movement. Proudly adopting a term that had once been used to insult Mexican Americans, Chicano activists demanded increased political power for Mexican Americans, education that recognized their cultural heritage, and the restoration of lands taken from them at the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848. One of the founding members, Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, launched the Crusade for Justice in Denver in 1965, to provide jobs, legal services, and healthcare for Mexican Americans. From this movement arose La Raza Unida, (Spanish for the United Race, or United People) a political organization that attracted many Mexican American college students. Elsewhere, Reies López Tijerina fought for years to recover lands that Hispanics lost to Whites when Mexican territory was taken by the United States in the 1840s. He also co-sponsored the Poor People’s March on Washington in 1967.

Some female Chicano activists worked on issues concerning Chicana women specifically. They formed the Comisión Femenil Mexicana Nacional and became involved in the case Madrigal v. Quilligan, obtaining a moratorium on the compulsory sterilization of women and adoption of bilingual consent forms. These steps were necessary because many Hispanic women who did not understand English well were being sterilized in the United States at the time, without proper consent. The prevalence of bilingual government documents is due in part to the work of these Chicano activist women.

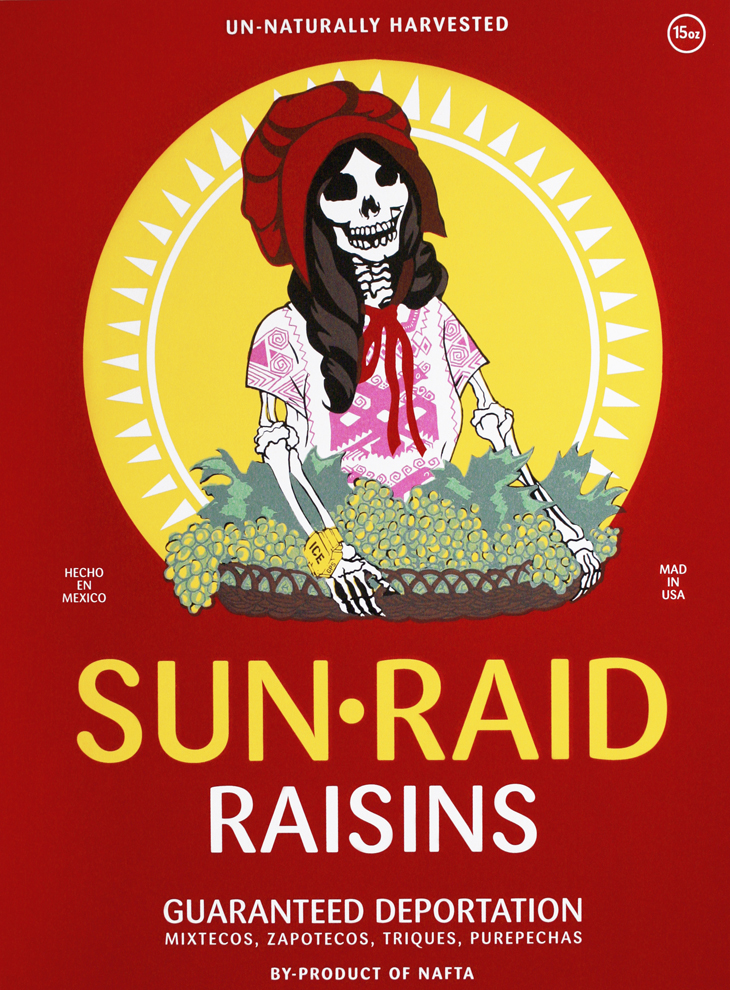

The Chicano Movement was important in the development of a sense of communal identity and pride. Part of that identity is based on the legacy of the American Southwest as the ancestral home of the Mexican people. This idea was promoted by Aberto Baltazar Urista Heredia who used the name Aztlán to refer to the lands of Northern Mexico that were annexed by the United States at the end of the Mexican-American War. Combined with the claim of some historical linguists and anthropologists that the original homeland of the Aztec peoples was located in the southwestern United States. The idea of Aztlán became a symbol for Chicano activists who believed they have a legal and primordial right to the land. In this sense, Hispanic immigrants moving into Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah and California are returning home rather than immigrating. Primary Source: Painting

Primary Source: Painting

Artwork with political themes is common in the Chicano Movement. This painting by Ester Hernandez criticizes the role of big business and government in the lives of farmworkers.

Like the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, the Chicano Movement was pushed forward by the work of talented artists and writers. Chicano artists have sought to affirm cultural identity by mixing Mexican, American and indigenous cultures. For example, the Virgin of Guadalupe, an important figure in Mexican culture, is used in a socio-political context by Chicano artists as a symbol of both hope in times of suffering, and empowerment, particularly when embodying an average woman or portrayed in an act of resistance. One of the most celebrated holidays in Mexican culture is the Day of the Dead and the symbols of the holiday have become a major component of the visual expression of the movement. Chicano art has drawn much influence from prominent muralists from the Mexican Renaissance, such as Diego Rivera and José Orozco, and has been similarly influenced by pre-Columbian art, where history and rituals were encoded on the walls of pyramids.

A favorite topic of Chicano artists is life in the barrios of Western cities. These Spanish-speaking neighborhoods have long histories of dislocation, marginalization, poverty, and inequity in access to social services. Chicano artists also use graffiti as a tool to express their political opinions, indigenous heritage, cultural and religious imagery, and counter-narratives to dominant portrayals of Chicano life in the barrios.

THE AMERICAN INDIAN MOVEMENT

The story of the first inhabitants of North America is long and tragic. Confronted with diseases from Europe, Asia and Africa, roughly 90% of all Native Americans died simply as a result of the joining of the Old and New Worlds. Over the centuries, Native Americans lost their land in a long series of failed wars and broken treaties. In the late 1800s, the last groups of Native Americans were forced onto reservations as their traditional way of life was destroyed. Official government policy was to assimilate them into mainstream White society, but they faced enormous hardships including poverty, lack of education, racism, and the fact that most Native Americans did not want to abandon their way of life.

In the 1930s, a set of laws known as the Indian New Deal was passed which officially ended the effort to destroy Native culture. While this was a positive step in the right direction, it did little to address the overwhelming poverty on the reservations. In 1970, the average life expectancy of Native Americans was 46 years compared to the national average of 69. The suicide rate was twice that of the general population, and the infant mortality rate was the highest in the country. Half of all Native Americans lived on reservations, where unemployment reached 50%. Among those in cities, 20% lived below the poverty line.

In 1968, a group of Indian activists, including Dennis Banks and George Mitchell convened a gathering of two hundred people in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and formed the American Indian Movement (AIM).

A year later, a small group of Native American activists landed on Alcatraz Island, the site of a notorious former federal prison, in San Francisco Bay. They announced plans to build a Native American cultural center, including a history museum, an ecology center, and a spiritual sanctuary. Supporters on the mainland provided supplies by boat, and celebrities visited Alcatraz to publicize the cause. More people joined the occupiers until, at one point, they numbered about 400. From the beginning, the federal government tried to persuade them to leave since the island was the property of the federal government. They were reluctant to accede, but over time, the occupiers began to drift away. Government forces removed the final holdouts by cutting off all water and electricity. Though fraught with controversy and forcibly ended, the 19-month occupation is hailed by many as a success for having attained international attention for the situation of Native Americans in the United States.

The next major demonstration came in 1972 when AIM members and others marched on Washington, DC in a journey they called the Trail of Broken Treaties. There, they occupied the offices of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The group presented a list of demands, which included improved housing, education, and economic opportunities in Native communities, the drafting of new treaties, the return of lands, and protections for Native religions and culture. One positive outcome of the political activism was the passage of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 which granted federal funds to tribes as grants which they could then administer as they believed was best suited for their needs. It was an important step in giving Native Americans control over their own affairs. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Members of AIM guard their positions outside the church at Wounded Knee during the standoff there in 1973.

The most dramatic event staged by AIM was the occupation of the town of Wounded Knee, South Dakota. In February 1973 they took control of the trading post and church and declared the town independent from the United States. Wounded Knee had historical significance for AIM since it was the site of a massacre of members of the Lakota tribe by the Army in 1890. The federal government surrounded the area. Armed only with rifles, the occupiers faced off with marshals, FBI agents and police armed with machine guns, helicopters, and armored personnel carriers. A siege ensued that lasted 71 days, with frequent gunfire from both sides, wounding a marshal as well as an FBI agent, and killing two Native Americans. When one of the occupiers was killed by a government sniper, tribal elders called an end to the occupation. Both sides reached an agreement to disarm and the occupiers began to leave the town.

Two AIM leaders, Dennis Banks and Russell Means, were arrested and put on trial, but charges were dropped when the jury was ready to acquit and the judge in their case ruled that the government had committed serious misconduct in the course of the trial.

By this time, the Nixon administration had already taken steps to address concerns AIM and other Native American activists had brought to their attention. The government restored millions of acres of land to tribal ownership, increased funding for Native American education, healthcare, legal services, housing, and economic development, and hired more Native employees in the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The greatest outcome of the standoff, however, was an increased sense of pride among Native Americans and public awareness of the plight of the nation’s first peoples.

The relationship between Native Americans and the federal government continues to be fraught. For many, the government is still viewed with suspicion. One member of AIM, Leonard Peltier has become a symbol of this mistrust. In 1977, he was convicted and sentenced to two consecutive terms of life imprisonment for the shooting of two FBI agents during a conflict on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Peltier’s conviction has been the subject of much controversy due to irregularities in his trial and campaigns to “Free Leonard Peltier” continue among Native American communities.

Contemporary Native American activists have criticized the use of mascots in sports, as perpetuating stereotypes. There has been a steady decline in the number of secondary school and college teams using such names, images, and mascots. Some tribal team names have been approved by the tribe in question, such as the Seminole Tribe’s approving the use of their name for the teams of Florida State University. Among professional teams, only the NBA’s Golden State Warriors discontinued use of Native American-themed logos in 1971. Controversy has remained regarding teams such as the NFL’s Washington Redskins, whose name is considered to be a racial slur, and MLB’s Cleveland Indians, whose usage of a caricature called Chief Wahoo has also faced protest.

Federal laws granted tribes to operate casinos on reservation lands even in states where gambling is illegal in an effort to provide reservations with a steady source of financial support. Although many Native American tribes have casinos, the impact of Native American gaming is widely debated. Some tribes, such as the Winnemem Wintu of California feel that casinos and their proceeds destroy culture from the inside out. These tribes refuse to participate in the gambling industry.

Sadly, even today Native Americans struggle to overcome the limitations of poverty on reservations and in larger society. Crime, alcoholism, drug use, lack of educational opportunities, and lack of access to financial resources all perpetuate the poverty that plagues modern reservations. For example, according to the Department of Justice, 1 in 3 Native women have suffered rape or attempted rape, more than twice the national rate, and in recent years, an alarming increase in teenage suicide has plagued many reservations.

DISABILITY RIGHTS

The idea of federal legislation enhancing and extending civil rights legislation to millions of Americans with disabilities gained bipartisan support in the late 1980s. In early 1989, both Congress and newly inaugurated President H. W. Bush worked separately, then jointly, to write legislation capable of expanding civil rights. Key activists played an important role in lobbying members of congress to develop and pass the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Patrisha Wright is known as “the General” for her work in coordinating the campaign to enact the ADA.

Although it may at first seem simple to legislate protections for people with disabilities, in fact, the law has proven to be controversial because it requires public accommodations to be made accessible. Included under the law are churches, private schools, motels, and restaurants. For many of these institutions, the cost of adding wheelchair ramps, lifts in swimming pools, or elevators was enormous. As a result, many church groups and business organizations lobbied against passage for the ADA. Pro-business conservative commentators in the media joined in opposition, writing that the Americans with Disabilities Act was “an expensive headache to millions” that would not necessarily improve the lives of people with disabilities.

Shortly before the act was passed, disability rights activists with physical disabilities coalesced in front of the Capitol Building, shed their crutches, wheelchairs, powerchairs and other assistive devices, and crawled and pulled their bodies up all 100 of the Capitol’s front steps. As the activists did so, many of them chanted “ADA Now”, and “Vote Now”. Some activists who remained at the bottom of the steps held signs and yelled words of encouragement. Jennifer Keelan, a second grader with cerebral palsy, was videotaped as she pulled herself up the steps, using mostly her hands and arms, saying, “I’ll take all night if I have to.” This direct action is reported to have convinced several senators to support the measure. While there are those who do not attribute much overall importance to this action, the Capitol Crawl of 1990 is seen by some present-day disability activists as a critical last push that made passage of the law a reality.

Certainly, there were supporters in Congress as well as champions of the law outside the Capitol. Senator Tom Harkin authored what became the final bill and was its chief sponsor in the Senate. Harkin delivered part of his introduction speech in sign language, saying it was so his deaf brother could understand.

Since passage, the law has remained controversial. Disabled rights activists have brought a long string of cases to court over such concerns as the failure to include enough accessible bathrooms in new buildings or poor website design that makes services unavailable to blind users. Although it seems unlikely that the ADA would be repealed, it remains a relatively new law in American life and the concerns of disabled Americans continue to be a subject the nation at large has not yet fully come to understand. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Members of the press and supporters gathered around Jennifer Keelan during the Capitol Crawl in 1990.

GAY RIGHTS

For most of America’s history, homosexuality was socially unacceptable and in most states, illegal. However, in the 20th Century, a gay community was active in many urban centers and after the end of World War II, a movement grew to eliminate the laws and customs which stigmatized and criminalized the lives of these Americans. A strong gay community grew in San Francisco especially, since it was the site of military bases were gay servicemen were dishonorably discharged.

During the Red Scare of the early 1950s, gay and lesbian government employees were also targeted. There was a concern that because they might not want others to know about their sexual orientation, they would be more susceptible to blackmail by Soviet agents. Whereas only a few people ever lost their jobs due to suspicion of actually being communist, many lost their jobs because they were homosexual. In 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower signed Executive Order 10450, which set security standards for federal employment and barred homosexuals from working in the federal government. Not only did the victims lose their jobs, but also they were forced out of the closet and thrust into the public eye as lesbian or gay. In 2004, historian David Johnson wrote about the era and coined the term the Lavender Scare to describe the persecution of homosexual federal employees that coincided with the more famous Red Scare. The term is derived from the euphemism “lavender lads” which Senator Everett Dirksen used for homosexuals at the time.

The catalyst for the modern gay rights movement took place not in San Francisco, however, but in New York City. Early in the morning of June 28, 1969, police raided a Greenwich Village gay bar called the Stonewall Inn. Although such raids were common, the response of the Stonewall patrons was not. As the police prepared to arrest many of the customers, especially transsexuals and cross-dressers, who were particular targets for police harassment, a crowd began to gather. Angered by the brutal treatment of the prisoners, the crowd attacked. Beer bottles and bricks were thrown. The police barricaded themselves inside the bar and waited for reinforcements. The riot continued for several hours and resumed the following night. Inspired by the brutality of the Stonewall Inn incident, various gay rights activist groups united to protest discrimination, homophobia, and violence against gay people, promoting gay liberation and gay pride.

With a call for homosexual men and women to come out, gay and lesbian communities moved from the urban underground into the political sphere. Gay rights activists protested strongly against the official position of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), which categorized homosexuality as a mental illness. This official classification often resulted in individuals being fired from their jobs or losing custody of their children. By 1974, the APA had ceased to classify homosexuality as a form of mental illness.

Public acceptance of homosexuality was advanced in 1974 when Kathy Kozachenko became the first openly lesbian woman elected to public office in Ann Arbor, Michigan. In 1977, Harvey Milk became California’s first openly gay elected man, although his service on San Francisco’s board of supervisors, along with that of San Francisco mayor George Moscone, was cut short by the bullet of a disgruntled former city supervisor.

While the Stonewall Inn incident may have catalyzed the homosexual community to mobilize for equal treatment, it was a health crisis in the 1980s that truly united them. In the early 1980s, doctors noticed a disturbing trend. Young gay men in large cities, especially San Francisco and New York, were being diagnosed with and dying from a rare cancer called Kaposi’s sarcoma. Because the disease was seen almost exclusively in male homosexuals, it was dubbed gay cancer. Doctors realized, however, that it often coincided with other symptoms, including a rare form of pneumonia, and they renamed it Gay Related Immune Deficiency (GRID), although people other than gay men, primarily intravenous drug users, were dying from the disease as well. The connection between gay men and the illness, later renamed Autoimmune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) led heterosexuals largely to ignore the growing health crisis in the gay community, wrongly assuming they were safe from its effects. The federal government also overlooked the disease, and calls for more money to research and find the cure were ignored. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

An ACT UP rally during the 1980s featuring signs with the pink triangle and Silence=Death slogan.

Tragically, the spread of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, was not well understood and the AIDS epidemic wreaked havoc in the gay community, the nation in general, and eventually in many parts of the world before governments found the political willpower to step in. Even after it became apparent that heterosexuals could contract the disease through blood transfusions and heterosexual intercourse, HIV/AIDS continued to be associated primarily with the gay community, especially by political and religious conservatives. Indeed, the Religious Right regarded it as a form of divine retribution meant to punish gay men.

With little help coming from the government, the gay community organized its own response. In 1982, New York City men organized a volunteer information hotline, provided counseling and legal assistance, and raised money for people with HIV/AIDS. Larry Kramer, one of the original members, left in 1983 and formed his own organization, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP). ACT UP took a more militant approach, holding demonstrations on Wall Street, outside the headquarters of the Food and Drug Administration, and inside the New York Stock Exchange to call attention to the crisis and shame the government into action. One of the images adopted by the group, a pink triangle paired with the phrase Silence=Death, captured media attention and became the symbol of the AIDS crisis. Primary Source: Photograph

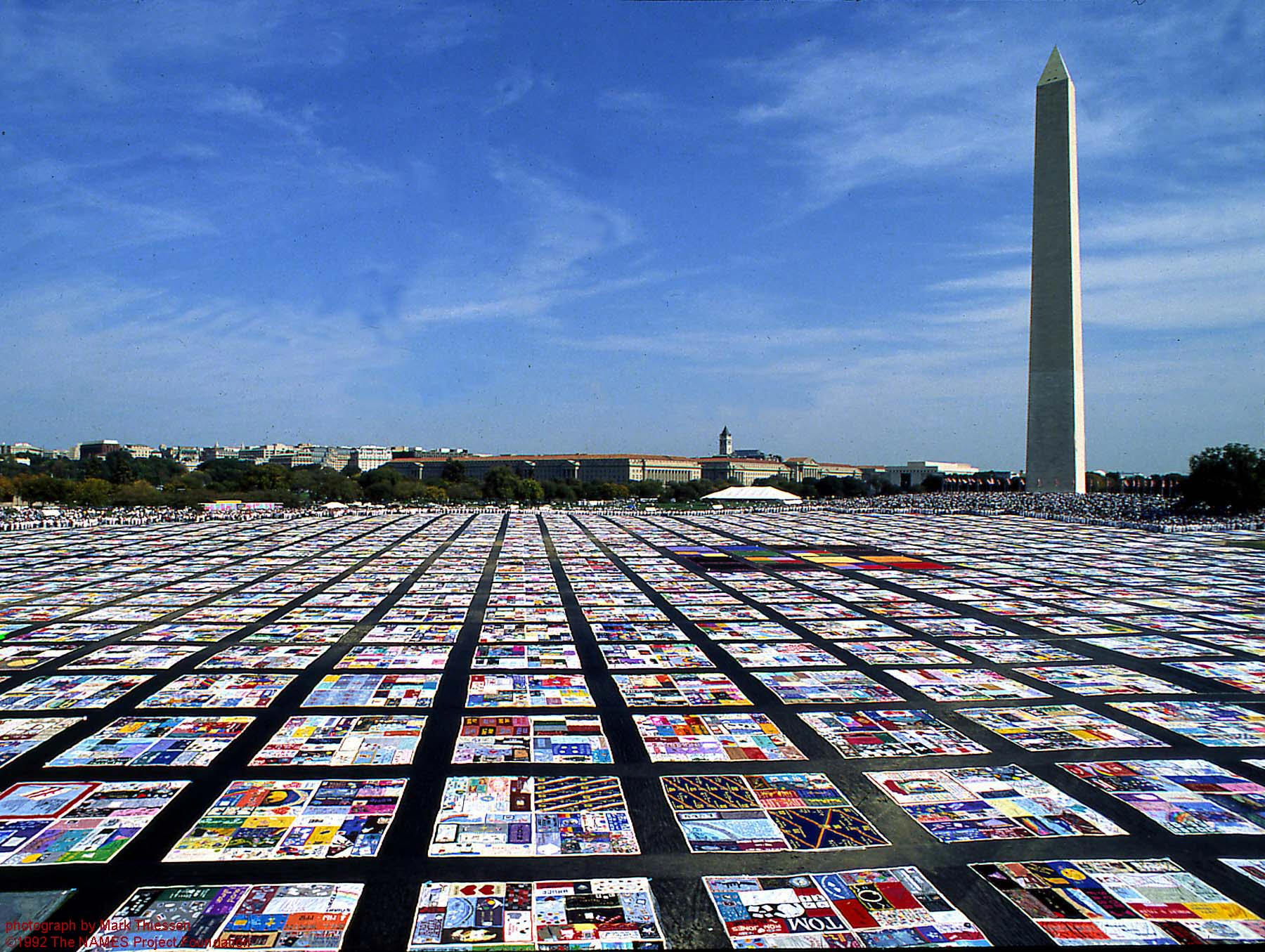

Primary Source: Photograph

The AIDS Memorial Quilt laid out on the National Mall in Washington, DC. The Quilt has become an important symbol for the gay rights movement and the movement to find a cure for HIV/AIDS.

One of the most powerful images associated with both the gay rights movement and the fight against AIDS has been the AIDS Memorial Quilt. The idea for the quilt was conceived in 1985 by activist Cleve Jones during the candlelight march in remembrance of Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone. For the march, Jones had people write the names of loved ones that were lost to AIDS-related causes on signs, and then they taped the signs to the old San Francisco Federal Building. All the signs taped to the building looked like an enormous patchwork quilt to Jones, and he was inspired to expand the project. At that time, many people who died of AIDS did not receive funerals, due to both the social stigma felt by surviving family members and the outright refusal by many funeral homes and cemeteries to handle the remains of those who had died from the disease. Lacking a memorial service or grave site, The Quilt became an opportunity for survivors to remember and celebrate their loved ones’ lives. The first showing of The Quilt was in 1987 on the National Mall in Washington, DC. The Quilt has since been displayed in sections around the world.

By the 1990s, the gay rights movement was beginning to find support in government. In January 1993, newly elected President Bill Clinton wanted to allow homosexuals to serve openly in the military, but to appease conservatives, adopted a policy of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. Under this policy, those on active duty would not be asked their sexual orientation and, if they were gay, they were not to discuss their sexuality openly or they would be dismissed from military service. This compromise satisfied neither conservatives seeking the exclusion of gays nor the gay community, which argued that homosexuals, like heterosexuals, should be able to live without fear of retribution because of their sexuality. Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell continued until 2011 when the military leadership, President Barack Obama and Congress all voted to end the policy and allow gay and lesbian military personnel to serve openly.

President Bill Clinton also proved himself willing to appease political conservatives when he signed into law the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), after both houses of Congress had passed it with such wide margins that a presidential veto could easily be overridden. DOMA defined marriage as a heterosexual union and denied federal benefits to same-sex couples. It also allowed states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages granted by other states. When Clinton signed the bill, he was personally opposed to same-sex marriage. Nevertheless, he disliked DOMA and later called for its repeal. Like many democratic politicians, he also later changed his position on same-sex marriage. On other social issues, however, Clinton was more liberal. He appointed openly gay and lesbian men and women to important positions in government and denounced discrimination against people with AIDS.

As the 2000s began, state governments began to challenge DOMA. Vermont became the first state to recognize civil unions, a legal agreement between two people that gave them the same rights as married couples. In this way, homosexual couples could own property together, adopt children, have next-of-kin access in cases of medical care, as well as seek financial support in the case of separation. For many, this was seen as a step forward and other states followed Vermont’s lead. Yet for many couples, a civil union would never mean the same as being married.

The first two decades of the new century saw same-sex marriage receive support from prominent figures in the African-American civil rights movement, including Coretta Scott King, John Lewis, Julian Bond, and Mildred Loving. In May 2011, national public support for same-sex marriage rose above 50% for the first time. In June 2013, the Supreme Court struck down DOMA in their United States v. Windsor decision, and finally in June 2015, the Supreme Court ruled in the case of Obergefell v. Hodges that the fundamental right of same-sex couples to marry on the same terms and conditions as opposite-sex couples is guaranteed by the Constitution. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

The = symbol and the slogan “Love Wins” became powerful images, especially in social media, during the campaign for marriage equality.

As with acceptance of gay marriage, the American public has grown increasingly accepting of homosexuality over the past two decades. Gay and lesbian actors have been cast in positive roles on television and movies. Professional athletes have come out and been accepted by teammates and fans. There are now Senators and Representatives in the Congress who are open about their sexual orientation. The corporate world has become equally accepting. In fact, in some ways the business community has pushed reluctant politicians toward acceptance because they do not want to lose potential customers.

CONCLUSION

The movements that were inspired by and followed the African American Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s varied in their makeup and success.

For the Mexican American farm workers of California, they found success through similar means. They marched and boycotted. They also were guided by charismatic leaders. However, they focused their efforts on working conditions rather than larger issues such as voting rights or police and housing discrimination.

The American Indian Movement took a decidedly more militant turn. Armed activists forcibly took possession of land and buildings and provoked confrontations with the government. Sometimes these standoffs were resolved peacefully, but tragically, not always. Similar to the African American community, the Native Americans found a sense of pride in their work, but only mixed results in courts and the halls of power.

Disabled Americans had a tremendous success with the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, but have had to go to court dozens of times to seek enforcement of the law’s provisions.

Most recently, homosexual Americans underwent a long struggle to advance their argument for a place at America’s table. Through protests, advocacy, and the courts, and in the face of health crisis and enormous prejudice, they have emerged in just the past few years with important victories at the national level.

What factors led to these successes, and what factors held these movements back? What combination of leadership, timing, method, and public support was responsible?

What do you think? What makes a movement successful?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: Other groups were inspired by the African Civil Rights Movement and worked to improve their own standing in society. Hispanics, disabled and LGBTQ Americans all worked successfully to advance their rights. While these movements were mostly peaceful, the American Indian Movement included violent confrontations with government.

Hispanic Americans had won important victories in the court system in the 1940s and 1950s similar to victories won by African Americans. However, the biggest victories were because of the work of Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers in California. They led a strike and boycott against grape growers and eventually won using nonviolence.

The Chicano Movement was a broader nationwide effort to promote Hispanic rights, identity and pride. It included organizing political groups, fighting for rights in the courts, and new music and art.

Native American activists formed AIM in 1968 to campaign for their rights. AIM occupied Alcatraz Island, led a march to Washington, DC where they occupied the offices of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and also led a standoff at Wounded Knee. In each of these cases, their movement was more violent than the African American and Hispanic efforts. However, laws were passed that gave Native American tribes more control over their land and finances, and the movement led to an increased sense of pride.

Disability rights activists worked to pass the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). They succeeded in 1990 and now business and organizations have to ensure that their buildings and services are accessible to people with disabilities. There is still some opposition to the law from groups who believe the requirements (such as installing elevators) are too expensive.

The gay rights movement stated in 1968 when police raided a gay bar in New York City and the customers fought back. The movement gained momentum due to the AIDS crisis in the 1980s when the disease first spread among gay men.

During the Red Scare of the 1950s, a law was passed to prohibit homosexuals from working for the government. In the 1990s, President Clinton implemented “don’t ask, don’t tell” which allowed homosexual Americans to serve in the military so long as they did not reveal their sexual orientation. This policy did not end until 2011. Today homosexual Americans can serve openly in the military and government.

Also during the 1990s, Americans started to debate gay marriage. Some states began allowing gay marriage while others banned it. A federal law allowed states to ignore gay marriages passed in other states. Eventually in 2015, the Supreme Court ruled that gay marriage was a constitutional right.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Cesar Chavez: Leader of the United Farm Workers and champion of the rights of Hispanic farm workers

Dolores Huerta: Co-founder of the National Farm Workers Association and champion of the rights of Hispanic farm workers.

Larry Itliong: Leader of the Filipino farm workers in California who merged his union with the Hispanic farm workers union led by Cesar Chavez to form the United Farm Workers.

United Farm Workers: Union of Filipino and Hispanic farm workers in California led by Cesar Chavez.

Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales: Mexican American boxer, poet, and one of the first political activists of the Chicano Movement.

La Raza Unida: Chicano political organization that was founded in the early 1970s and became prominent throughout Texas and Southern California where its members ran for office in local elections.

Reies López Tijerina: Chicano political activist who helped Hispanics reclaim lands their families had lost when the United States took the Southwest from Mexico in the 1840s.

Dennis Banks: Native American activist and co-founder of the American Indian Movement (AIM) along with George Mitchell.

George Mitchell: Native American activist and co-founder of the American Indian Movement (AIM) along with Dennis Banks.

American Indian Movement (AIM): Native American political organization founded in 1968. They organized various protests including the occupation of Alcatraz Island, Trail of Broken Treaties and occupation of Wounded Knee.

Russell Means: American Indian Movement activist and one of the leaders of the Wounded Knee occupation. He went on to a career in Hollywood but continued to advocate for Native American rights.

Leonard Peltier: Native American activist and AIM member who was convicted in 1977 of the murder of two FBI agents. He has become a symbol of the conflict between Native Americans and the federal government.

Harvey Milk: First openly gay man elected to a public office in the United States. He served on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors until he was murdered.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Aztlán: Mythical name for the lands of Northern Mexico that were annexed by the United States at the end of the Mexican-American War. The idea of Aztlán has been used to develop as sense of communal identity by Chicano activists.

Civil Union: A legal agreement between homosexual partners that served as a substitute for marriage in some states. It granted the same legal rights as marriage without the title.

![]()

SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY

AIDS: Illness caused by HIV that was first detected in the 1980s and mistakenly believed to infect only gay men. It devastated the gay community and because the federal government was slow to respond to the growing crisis, sparked organization and activism in the gay community.

![]()

COURT CASES

Mendez v. Westminster: 1947 court case that ended segregated schools for Hispanic students.

Hernandez v. Texas: 1954 Supreme Court case in which the court concluded that Fourteenth Amendment protections should be extended to all ethnic groups. Specifically in this case, Hernandez argued that he should not be tried by an all-White jury.

Madrigal v. Quilligan: Court case in which Spanish-speaking women had been sterilized after signing documents they could not read. The case resulted in forms being published in multiple languages.

Obergefell v. Hodges: 2015 Supreme Court case that declared gay marriage constitutional in all 50 states.

![]()

EVENTS

Delano Grape Strike and Boycott: Major strike and boycott during the 1960s in California by the United Farm Workers to win guarantees of humane treatment of workers and better pay.

Chicano Movement: Movement of Hispanic Americans beginning in the 1960s that focused on civil rights. It involved the development of political institutions and was marked by an increased sense of community pride as well as a flowering of artistic expression and literature.

Occupation of Alcatraz Island: Political occupation of an island in San Francisco by members of AIM in 1969-1970.

Trail of Broken Treaties: Pilgrimage from California to Washington, DC in 1972 organized by AIM and other Native American activists. Once in DC, they occupied the offices of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and presented a list of demands to be read by President Nixon.

Occupation of Wounded Knee: Violent 71-day standoff between AIM activists and the federal government in 1973.

Capitol Crawl: Protest in 1990 in which disabled Americans crawled up the steps of the Capitol Building in Washington, DC without their wheelchairs, canes, etc. to push for passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Lavender Scare: Persecution of homosexual federal employees during the early 1950s that coincided with the hunt for communists.

Stonewall Inn Riots: Violent confrontation between New York City police and gay men at a bar in 1969. The event sparked the modern gay rights movement.

AIDS Memorial Quilt: Collection of sewn memorials to Americans who died from AIDS and AIDS-related illnesses. It was first displayed in full in Washington, DC on the National Mall.

![]()

LAWS & POLICIES

Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975: Law passed in 1975 that gave federal money to Native American tribes in the form of grants that the tribes could spend as they wished. It was in important step in allowing Native Americans great self-government.

Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA): 1990 law that guaranteed protections to people with disabilities, including signage in Braille, wheelchair ramps, access lifts, handicapped parking spaces, etc.

Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell: Policy adopted by the Clinton Administration in the 1990s that allowed homosexual Americans to serve in the military so long as they didn’t reveal their sexual orientation. In turn, the military would not actively try to find out their orientation. It ended the days of an open ban on service.

Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA): Law passed in 1996 that defined marriage as between one man and one woman. It prohibited the federal government from recognizing gay marriages and allowed states to ignore gay marriages issued in other states. It was overturned in 2015.

After DOMA was signed, were there an increase or decrease of gay couples who went out to fight for a change?

Since people didn’t support ADA because it was costly, did the government do anything to help pay for the expenses?

Was there any companies or groups that emerged to go against the ADA?

How long did the change for Americans with Disabilities Act take to shift the ways businesses work?

Did people fight for gay rights during the lavender lads ages?

African Americans and other minorities today continue to fight for their rights. How have they used what they learn from these movement to advance their cause and what do they do differently?

What did it take for the homosexuality representatives to be elected in 1974?

What happened to Cesar Chavez?

Why was it that during that time the gay rights movement they were also prevented rights to fertility?

How influential was the Civil Rights movement around other parts of the world. Did anyone else take direct inspiration from the movement or King himself?

Did Clinton feel any guiltiness when he initiated DOMA?

I’d think them passing homosexuality as a “mental illness,” is just an excuse for them to not accept it.

I agree to be honest, like there was no freedom to be who they were.

Did people think being lgbtq+ was a mental illness because it was out of the “normal”?

Why do people think that it’s so wrong to like the same gender?

How was it proven that liking the opposite gender was a mental illness?

Where did AIDS and HIV originate?

What impact did the Native American cultural center at Alcatraz Island have?

Why were there so much discrimination and prejudice when this nation was built upon “all men are created equal”?

Approximately how many parents lost custody of their children due to being homosexual? This is a very unfortunate situation for parents and individuals who weren’t accepted in society.

What’s the average age that people come out during this time? Are there any cases of kids getting bullied at school because of their homosexual back in the day?

Do certain places or organizations still refuse to abide with the ADA?

Did the Wounded Knee return to US government control afterwards?

I think Wounded Knee did get returned to the US government afterward. I think that on the side of the Native Americans they didn’t want anyone else to get hurt and that they had to make an agreement.

Are there any other symbols such as the AIDS Memorial Quilt that represent any sort of group or movement, and why?

Through reading this whole chapter, and this section I could not help but think about the recent events that have occurred during the past year. I found this online resource that talks about the Civil Rights Movement of the past and it compares the events of the past to current social justice movements that are still occurring.

Link: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/what-is-unprecedented-about-this-years-racial-justice-protests

What was life like for a closeted person in the military during the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Policy”?

Would the issue of gay right disappear in the next few decades?