PRINT VERSION

JUMP TO

TRANSLATE

INTRODUCTION

Our federal government is expansive and integrated into much of our everyday lives. We receive the mail, pay taxes, drive on federally funded highways, store our food refrigerators that comply with federal-mandates for efficiency, are paid a federal minimum wage, put on seat belts required by law and plan to pay for college in part with government scholarships.

This was not always the case. In fact, when the nation was founded the only interaction most Americans had with their federal government at any point in their entire lives was when they sent or received the mail. Over time, the government took on more and more responsibility, but at the dawn of the 1930s, few Americans paid federal taxes, and there was little regulation of banking or business. All that changed with the new president’s New Deal. For Hoover, the primary responsibility of caring for people fell to the people themselves. For Roosevelt, that responsibility rested with the government.

This is a radical idea that has become less radical in the ensuing decades. Today we take for granted the idea that the government exists to watch out for us. We know that our government will protect us from dangerous foods, dangerous drivers, shady business practices, and support us when we lose our jobs and suffer through natural disasters. But, is this the right role of government? Should we expect our government to take care of us, or are we our own our personal responsibility?

What do you think? Should the government be responsible for the welfare of everyone?

THE ONLY THING WE HAVE TO FEAR

March 4, 1933, dawned gray and rainy. Roosevelt rode in an open car along with outgoing president Hoover, facing the public, as he made his way to the Capitol Building. Hoover’s mood was somber, still personally angry over his defeat in the general election the previous November. He refused to crack a smile at all during the ride among the crowd, despite Roosevelt’s urging to the contrary. At the ceremony, Roosevelt rose with the aid of leg braces equipped under his specially tailored trousers and placed his hand on a Dutch family Bible as he took his solemn oath. At that very moment, the rain stopped and the sun began to shine directly on the platform, and those present would later claim that it was as though God himself was shining down on Roosevelt and the American people.

Bathed in the sunlight, Roosevelt delivered one of the most famous and oft-quoted inaugural addresses in history. He encouraged Americans to work with him to find solutions to the nation’s problems and not to be paralyzed by fear. Roosevelt called upon all Americans to assemble and fight an essential battle against the forces of economic depression. He famously stated, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” Upon hearing his inaugural address, one observer in the crowd later commented, “Any man who can talk like that in times like these is worth every ounce of support a true American has.” Foregoing the traditional inaugural parties, the new president immediately returned to the White House to begin his work to save the nation.

BANK RELIEF

In days past, depositing money in a savings account carried a degree of RISK. If a bank made bad investments and was forced to close, individuals who did not withdraw their money fast enough found themselves out of luck. Sometimes a simple rumor could force a bank to close. When depositors feared a bank was unsound and began removing their funds, the news would often spread to other customers. This often caused a panic, leading people to leave their homes and workplaces to get their money before it was too late.

These runs on banks were widespread during the early days of the Great Depression. In 1929 alone, 659 banks closed their doors. By 1932, an additional 5,102 banks went out of business. Families lost their life savings overnight. Thirty-eight states had adopted restrictions on withdrawals in an effort to forestall the panic. Bank failures increased in 1933, and Franklin Roosevelt deemed remedying these failing financial institutions his first priority after being inaugurated.

Within 48 hours of his inauguration, Roosevelt proclaimed an official bank holiday and called Congress into a special session to address the crisis. The resulting Emergency Banking Act of 1933 was signed into law on March 9, 1933, a scant eight hours after Congress first saw it. The law officially took the country off the gold standard, a restrictive practice that, although conservative and traditionally viewed as safe, severely limited the circulation of paper money. Those who held gold were told to sell it to the U.S. Treasury for a discounted rate of a little over $20 per ounce. Furthermore, dollar bills were no longer redeemable in gold. The law also gave the comptroller of currency the power to reorganize all national banks faced with insolvency, a level of federal oversight seldom seen prior to the Great Depression. Between March 11 and March 14, auditors from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, the Treasury Department, and other federal agencies swept through the country, examining each bank. By March 15, 70% of the banks were declared solvent and allowed to reopen.

On March 12, the day before the banks were set to reopen, Roosevelt demonstrated his mastery of America’s new form of communication and gave his first radio address to the American people, explaining what the bank examiners had been doing over the previous week. He assured people that any bank open the next day had the federal government’s stamp of approval. The combination of his reassuring manner and the promise that the government was addressing the problems worked wonders in changing the popular mindset. Just as the culture of panic had contributed to the country’s downward spiral after the crash, so did this confidence-inducing move help to build it back up. Consumer confidence returned, and within weeks, close to $1 billion in cash and gold had been brought out from under mattresses and hidden bookshelves, and re-deposited in the nation’s banks. The immediate crisis had been quelled, and the public was ready to believe in their new president. Primary Source: Government Document

Primary Source: Government Document

The official plaque placed in banks announcing that they participate in the FDIC and that a depositor’s money is guaranteed by the US government. The FDIC was an essential part of the New Deal and helped prevent future bank runs.

In June 1933, Roosevelt replaced the Emergency Banking Act with the more permanent Glass-Steagall Act. This law prohibited commercial banks from engaging in investment banking, therefore stopping the practice of banks speculating in the stock market with deposits. This law also created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, or FDIC, which insured personal bank deposits up to $2,500. With FDIC protection, Americans knew that if their bank failed, the government would reimburse them. The effect was an end of bank runs. The amount insured has since been increased.

Other measures designed to boost confidence in the overall economy beyond the banking system included passage of the Economy Act, which fulfilled Roosevelt’s campaign pledge to reduce government spending by reducing salaries, including his own and those of the Congress. He also signed into law the Securities Act, which required full disclosure to the federal government from all corporations and investment banks that wanted to market stocks and bonds. Roosevelt also sought new revenue through the Beer Tax. As the Twenty-First Amendment, which would repeal the Eighteenth Amendment establishing Prohibition, moved towards ratification, this law authorized the manufacture of 3.2% beer and levied a tax on it.

HOMEOWNERS

The final element of Roosevelt’s efforts to provide relief to those in desperate straits was the Home Owners’ Refinancing Act. Created by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), the program rescued homeowners from foreclosure by refinancing their mortgages. Not only did this save the homes of countless homeowners, but it also saved many of the small banks who owned the original mortgages by relieving them of the refinancing responsibility. Later New Deal legislation created the Federal Housing Authority (FHA), which eventually standardized the 30-year mortgage and promoted the housing boom of the post-World War II era. A similar program, created through the Emergency Farm Mortgage Act and Farm Credit Act, provided the same service for farm mortgages. The FHA remains an important government agency in today’s housing market – one of the legacies of the New Deal.

JOBS

Out of work Americans needed jobs. To the unemployed, many of whom had no money left in the banks, a decent job that put food on the dinner table was a matter of survival. Unlike Herbert Hoover, who refused to offer direct assistance to individuals, Franklin Roosevelt knew that the nation’s unemployed could last only so long. Like his banking legislation, aid would be immediate. Roosevelt adopted a strategy known as pump priming. To start a dry pump, a farmer often has to pour a little water into the pump to generate a heavy flow. Likewise, Roosevelt believed the national government could jump-start a dry economy by pouring in a little federal money. The first major help to large numbers of jobless Americans was the Federal Emergency Relief Act (FERA). This law gave $3 billion to state and local governments for direct relief payments. Under the direction of Harry Hopkins, FERA assisted millions of Americans in need. While Hopkins and Roosevelt believed this was necessary, they were reticent to continue this type of aid. Direct payments were important in preventing starvation and homelessness, but simply giving away money could stifle the initiative of Americans seeking paying jobs. Although FERA lasted two years, efforts were soon shifted to work-relief programs that would pay individuals to perform jobs, rather than provide handouts.

The first such initiative began in March 1933. Called the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), this program was aimed at over two million unemployed unmarried men between the ages of 17 and 25. CCC participants left their homes and lived in camps in the countryside. Subject to military-style discipline, the men built reservoirs and bridges, and cut fire lanes through forests. They planted trees, dug ponds, and cleared lands for camping. They earned $30 dollars per month, most of which was sent directly to their families. The CCC was extremely popular. Listless youths were removed from the streets and given paying jobs and provided with room and shelter. Many of the nation’s parks and trails were built or improved by the men of the CCC. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

A CCC work team stopped to eat lunch while on a job in Virginia. Hundreds of parks were improved during the 1930s as part of this innovative program.

There were plenty of other opportunities for the unemployed in the New Deal. In the fall of 1933, Roosevelt authorized the Civil Works Administration. Also headed by Hopkins, this program employed 2.5 million in a month’s time, and eventually grew to a multitudinous 4 million at its peak. Earning $15 per week, CWA workers tutored the illiterate, built parks, repaired schools, and constructed athletic fields and swimming pools. Some were even paid to rake leaves. Hopkins put about three thousand writers and artists on the payroll as well. There were plenty of jobs to be done, and while many scoffed that the government was simply inventing busy work as an excuse to give away money , it provided vital relief during trying times.

The largest relief program of all was the Works Progress Administration (WPA). When the CWA expired, Roosevelt appointed Hopkins to head the WPA, which employed nearly 9 million Americans before its expiration. Americans of all skill levels were given jobs to match their talents. Most of the resources were spent on public works programs such as roads and bridges, but WPA projects spread to artistic projects too.

The Federal Theater Project hired actors to perform plays across the land. Artists such as Ben Shahn beautified cities by painting larger-than-life murals. Even such noteworthy authors as John Steinbeck and Richard Wright were hired to write regional histories. WPA workers took traveling libraries to rural areas. Some were assigned the task of transcribing documents from colonial history while others were assigned to assist the blind.

Critics called the WPA “We Piddle Around” or “We Poke Along,” labeling it the worst waste of taxpayer money in American history. But most every county in America received some service by the newly employed, and although the average monthly salary was barely above subsistence level, millions of Americans earned desperately needed cash, skills, and self-respect.

Another government program designed to provide jobs was the Public Works Administration (PWA). The PWA set aside $3.3 billion to build public projects such as highways, federal buildings, and military bases. Although this program suffered from political squabbles over appropriations for projects in various congressional districts, as well as significant underfunding of public housing projects, it ultimately offered some of the most lasting benefits of the NIRA. Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes ran the program, which completed over thirty-four thousand projects, including the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco and the Queens-Midtown Tunnel in New York. Between 1933 and 1939, the PWA accounted for the construction of over one-third of all new hospitals and 70% of all new public schools in the country.

FARMERS

While most Americans enjoyed relative prosperity for most of the 1920s, the Great Depression for the American farmer really began after World War I. Much of the 1920s was a continual cycle of debt for the American farmer, stemming from falling farm prices and the need to purchase expensive machinery. When the stock market crashed in 1929, sending prices in an even more downward cycle, many American farmers wondered if their hardscrabble lives would ever improve.

The first major New Deal initiative aimed to help farmers by attempting to raise farm prices was the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). One method of driving up prices of a commodity is to create artificial scarcity. Simply put, if farmers produced less, the prices of their crops and livestock would increase. The AAA identified seven basic farm products: wheat, cotton, corn, tobacco, rice, pigs, and milk. Farmers who produced these goods would be paid by the AAA to reduce the amount of acres in cultivation or the amount of livestock raised. In other words, farmers were paid to farm less!

The press and the public immediately cried foul. To meet the demands set by the AAA, farmers plowed under millions of acres of already planted crops. Six million young pigs were slaughtered to meet the subsidy guidelines. In a time when many were out of work and tens of thousands starved, this wasteful carnage was considered blasphemous and downright wrong.

But farm income did increase under the AAA. Cotton, wheat, and corn prices doubled in three years. Despite having misgivings about receiving government subsidies, farmers overwhelmingly approved of the program. Unfortunately, the bounty did not trickle down to the lowest economic levels. Tenant farmers and sharecroppers did not receive government aid; the subsidy went to the landlord. The owners often bought better machinery with the money, which further reduced the need for farm labor. In fact, the Great Depression and the AAA brought a virtual end to the practice of sharecropping in America.

The Supreme Court put an end to the AAA in 1936 by declaring it unconstitutional. By this time the Roosevelt administration decided to repackage the agricultural subsidies as incentives to save the environment as a response to the Dust Bowl. The Soil Conservation And Domestic Allotment Act paid farmers to plant clover and alfalfa instead of wheat and corn. These crops return nutrients to the soil. At the same time, the government achieved its goal of reducing crop acreage of the key commodities.

Another major problem faced by American farmers was mortgage foreclosure. Unable to make the monthly payments, many farmers were losing their property to their banks. Across the Corn Belt of the Midwest, the situation grew desperate. Farmers pooled resources to bail out needy friends. Minnesota and North Dakota passed laws restricting farm foreclosures. Vigilante groups formed to intimidate bill collectors. In Le Mars, Iowa, an angry mob beat a foreclosing judge to the brink of death in April 1933.

FDR intended to stop the madness. The Farm Credit Act, passed in March 1933 refinanced many mortgages in danger of going unpaid. The Frazier-Lemke Farm Bankruptcy Act allowed any farmer to buy back a lost farm at a low price over six years at only 1% interest. Despite being declared unconstitutional, most of the provisions of Frazier-Lemke were retained in subsequent legislation.

In 1933, only about one out of every ten American farms was powered by electricity. The Rural Electrification Authority addressed this pressing problem. The government embarked on a mission of getting electricity to the nation’s farms. Faced with government competition, private utility companies sprang into action, sending power lines to rural areas with a speed previously unknown. By 1950, nine out of every ten farms enjoyed the benefits of electric power.

COMMUNICATION

Roosevelt believed that his administration’s success depended upon good communication with voters and the best way for him to do so was through radio. Roosevelt’s opponents had control of most newspapers in the 1930s which meant that his messages were filtered before the public read them. Historian Betty Houchin Winfield wrote, “He and his advisers worried that newspapers’ biases would affect the news columns and rightly so.” Historian Douglas B. Craig wrote that by using radio, Roosevelt “offered voters a chance to receive information unadulterated by newspaper proprietors’ bias…” Primary Source: Photograph

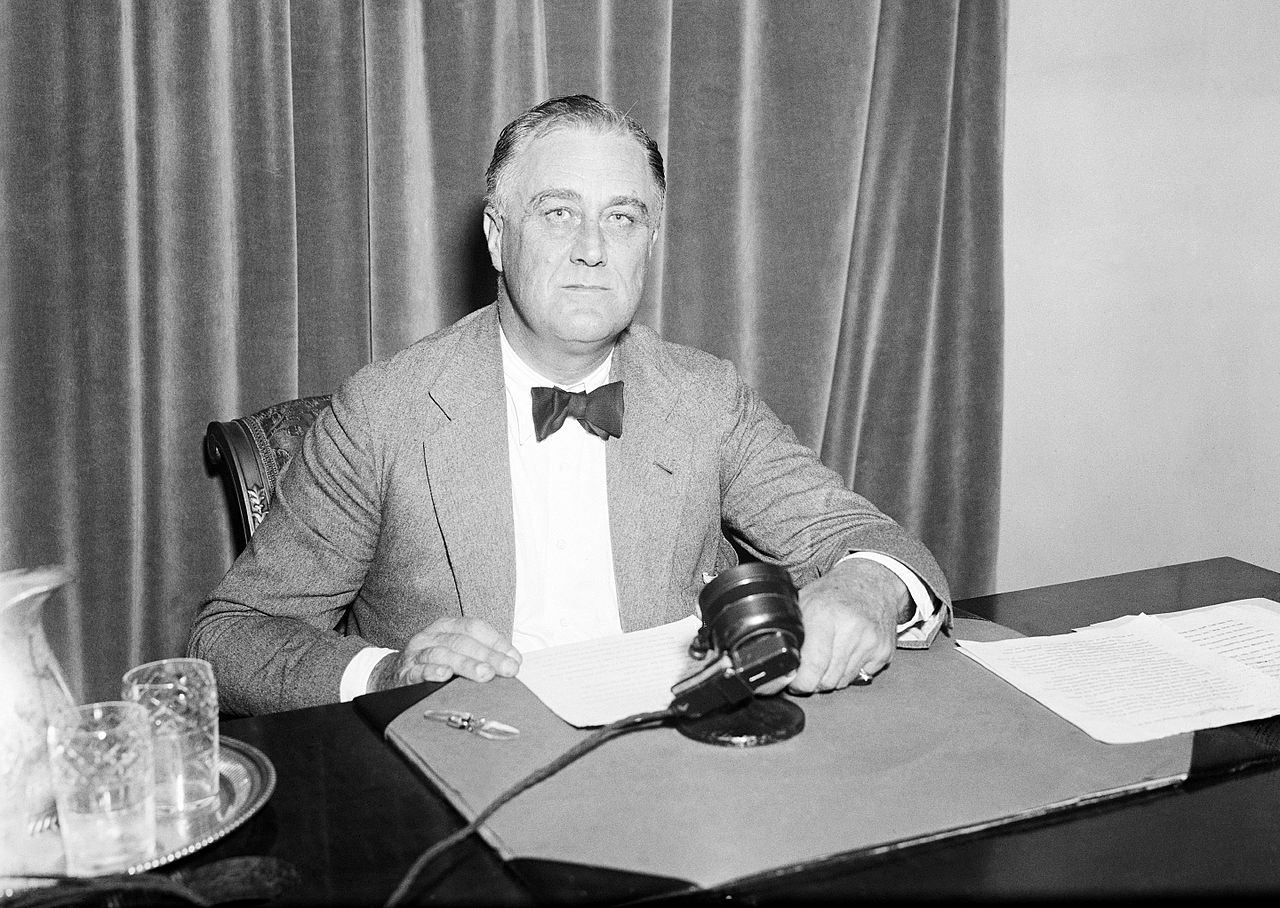

Primary Source: Photograph

FDR sitting down for one of his fireside chats. Appearances mattered little during these speeches since they were heard on the radio. Their effect was tremendous since the president’s soothing tone put many voters concerns to rest.

Roosevelt offered his messages in the form of simple conversations he imagined friends might have sitting by the fireside in the evening after dinner. These fireside chats eventually numbered 30 between 1933 and 1944. Roosevelt spoke about New Deal initiatives, and later the course of World War II. On radio, he was able to quell rumors and explain his policies. His tone and demeanor communicated self-assurance during times of despair and uncertainty. Roosevelt was regarded as an effective communicator on radio, and the fireside chats kept him in high public regard throughout his presidency. He is remembered as a master of communication, both for the content of his messages and for his ability to effectively make use of the new medium.

EVALUATING THE FIRST NEW DEAL

It would be a mistake to give the president solo credit for all of the good things that the New Deal accomplished, just as it is unfair to blame Hoover for all of the ills of the Depression. Roosevelt certainly did not do everything himself. It was the hard work of his advisors – the so-called Brain Trust of scholars and thinkers from leading universities he tapped to help plan and implement that New Deal – as well as Congress and the American public who helped the New Deal succeed as well as it did. Ironically, it was the American people’s volunteer spirit, so extolled by Hoover, that Roosevelt was able to harness. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

FDR signs a bill surrounded by members of his cabinet and other advisors and supporters. The new president’s team were nicknamed the Brain Trust since many of them had come from academia.

The first hundred days of his administration was not a master plan that Roosevelt dreamed up and executed on his own. In fact, it was not a master plan at all, but rather a series of, at times, disjointed efforts made from different assumptions. But after taking office and analyzing the crisis, Roosevelt and his advisors felt that they had a larger sense of what had caused the Great Depression and thus attempted a variety of solutions to fix it. They believed that it was caused by abuses on the part of a small group of bankers and businessmen, aided by Republican policies that built wealth for a few at the expense of many.

The answer, they felt, was to root out these abuses through banking reform, as well as adjust production and consumption of both farm and industrial goods. This adjustment would come about by increasing the purchasing power of everyday people, as well as through regulatory policies like the NRA and AAA. While it may seem counterintuitive to raise crop prices and set prices on industrial goods, Roosevelt’s advisors sought to halt the deflationary spiral and economic uncertainty that had prevented businesses from committing to investments and consumers from parting with their money.

Many Americans were pleased with the president’s bold plans. Roosevelt had reversed the economy’s long slide, put new capital into ailing banks, rescued homeowners and farmers from foreclosure and helped people keep their homes. The New Deal offered some direct relief to the unemployed poor but more importantly, it gave new incentives to farmers and industry alike, and put people back to work. The total number of working Americans rose from 24 to 27 million between 1933 and 1935. Perhaps most importantly, Roosevelt’s first term New Deal programs had changed the pervasive pessimism that had held the country in its grip since the end of 1929. For the first time in years, people had hope.

CONCLUSION

During the first 100 days of the Roosevelt Administration the role government played in the lives of everyday Americans radically shifted. People had always entrusted their leaders with the responsibility of protecting them from outside attack and preserving peace within their borders, but had not viewed their government as being responsible for protecting them from hardship. The idea that the government would help you find a job, or make sure you were paid a living wage, was entirely novel. And it has been a responsibility the government has never given back. If anything, we have become more accustomed to the idea that our leaders owe us protection from unemployment, or protection when we cannot pay our mortgage.

Is this a good thing? Should we live in a nation in which we expect our government to behave as a sort of mother hen, watching carefully over her flock of citizens? Is this power we never should have given away? Or, is it a just and wise expansion of government?

What do you think? Should the government be responsible for the welfare of everyone?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: FDR tried to deal with the immediate problems facing the country by creating many new government programs. These stabilized the banking system, gave people jobs and addressed food shortages.

President Franklin Roosevelt told Americans the only thing they had to fear was fear itself. He implemented many new programs to try to solve the problem. Most involved spending large amounts of government money to jumpstart the economy.

His programs became known as the New Deal. In the first 100 days of his presidency, FDR implemented programs to help solve the banking crisis, to give people jobs, and to support farmers. Many of the New Deal programs are known by their acronyms. (FDIC, FHA, CCC, WPA, AAA, etc.)

FDR was an excellent communicator. He was known for his speeches on the radio in which he explained his ideas in simple terms that regular Americans could understand.

Part of the New Deal were laws to fix the banking system. One program gives insurance to people who deposit money in banks so they will not lose it if their bank fails. This program prevents bank runs. Other financial programs provided regulation for the stock market.

New government programs helped people get loans to buy houses.

To help people find jobs, FDR created programs building roads, bridges, dams, parks, trails, painting murals, writing, acting, and much more.

For farmers, FDR signed laws paying farmers to grow less. This stabilized food prices. The New Deal also included programs to provide electricity to rural areas.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Harry Hopkins: Secretary of Commerce and one of Franklin Roosevelt’s closest advisors. He was one of the architects of the New Deal.

Harold Ickes: Secretary of the Interior who ran the Public Works Administration and was an important advisor to Franklin Roosevelt.

Brain Trust: Nickname for the group of advisors Franklin Roosevelt assembled to help solve the Great Depression. Many had come from universities, thus giving rise to the nickname.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Pump Priming: Idea that the government should spend during an economic downturn, thus putting money into the economy which will in turn be spent by individuals and private businesses. Without the government’s initial investment, recovery would not have been possible.

First Hundred Days: The nickname for the first few months of Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency in which he was able to work with Congress to pass numerous laws that established the beginning of the New Deal.

![]()

GOVERNMENT AGENCIES

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC): Government agency with provides insurance for individual depositors at commercial banks, thus preventing bank runs.

Federal Housing Authority (FHA): Government agency that provides backing for home loans and helped stabilized the housing market during the Great Depression, as well as spur the housing boom in the post-WWII era.

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC): New Deal program that provided jobs to young men building parks, trails, reservoirs, bridges and fire lanes.

Works Progress Administration (WPA): Major New Deal program that provided jobs to 9 million Americans building major infrastructural projects such as bridges, and roads, but also writing and painting murals as well.

Public Works Administration (PWA): New Deal program that provided jobs building highways, federal buildings and military bases. Among the programs projects were the Golden Gate Bridge and Queens-Midtown Tunnel. Over 1/3 of all hospitals and 70% of all new schools built in the 1930s were completed by workers in this program.

Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA): New Deal agency that provided payments to farmers to lower agricultural production. The program broke a cycle in which farmers increased output in an effort to increase returns. In reality, excessive output drove up supply and drove down prices.

Rural Electrification Authority: New Deal agency that worked to provide electricity to rural areas.

![]()

SPEECHES

FDR’s First Inaugural Address: Famous speech given on March 4, 1933 in which incoming President Franklin D. Roosevelt said “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

Fireside Chat: Nickname for President Franklin Roosevelt’s radio speeches in which he tried to use plain language to explain his ideas.

![]()

LAWS

Emergency Banking Act of 1933: One of the first pieces of New Deal legislation. It took the country off the gold standard and helped stabilize the banking system.

Glass-Steagall Act: Replacement for the Emergency Banking Act of 1933. This law prohibited commercial banks from engaging in investment banking and created the FDIC.

Federal Emergency Relief Act (FERA): New Deal legislation that gave $3 billion to state and local governments for direct payments to needy Americans. It provided help to prevent people from losing their homes or starving, but did not provide work.

If Roosevelts advisors, Brain Trust, didn’t exist, would there have been a big difference?

If a set of programs like the New Deals were implemented today, what kind of reaction would there have been in society now?

Looking back now and seeing what each initiative’s impact was, were they all actually effective in their goals? Was there more that they could have done or other angles to take to improve the situation of the Great Depression?

Looking back on how little attention farmers received for many of the problems brought by the Depression, it’s great to see how far the government has gone to make a difference. Especially having electricity to step in by then.

If a situation like the Great Depression never happened, would something like a President running for more than two terms be accepted by the people?

I wonder if Hoover would be disappointed in FDR’s plan to help the Depression because he did things to help the people directly, while Hoover just gave Americans a push in the rights direction.

What are some of the more recent Acts that helped out the people?

If Roosevelt didn’t have all of those advisor especially Brian Trust, would he be able to make the new deal?

Did the CCC give jobs to all men or just white men?

What if Roosevelt didn’t create the New Deal? Would he have brought down America like Hoover did?

The CCC gave jobs to men, but what about women?

How much of an impact have FDR’s idea of the government being a mother hen to us played in todays world?

If it wasn’t for President Hoover, would President Roosevelt be disliked and clueless during his time as president? His actions as president were based off of Roosevelt’s because he knew what the people wanted and hated from Roosevelt’s time as president.

Were there any other president(s) that was at least remotely close to carrying out many tasks like how President Roosevelt did?

What made FDR’s inaugural address speech so impactful?

Were there ever rumors revolving around President Roosevelt that he was able to dismiss using his fireside chats?

I feel like Hoover and Roosevelt are like opposites. Hoover doesn’t want to be direct and tries to let the problems fix itself, while Roosevelt makes so many of the programs to help the people directly. He even talks directly to the people with his fireside chats

I completely agree. Thats how Hoover had his downfall, he relied way too much on individualism while Roosevelt was able to read the problem and help the country rise from the depression

How did these new acts affect those apart of marginalized groups? Did it help those who lived in wealthy areas/ were white/ privileged more?

If President Hoover ran another term, would he have been as successful as President Roosevelt?

LOL let me rephrase. If he was given a second chance, would he have taken advantage of it and fix his past mistakes???

Did the CCC create any jobs for women so that they could try to make money for their family as well, and not just the men?

What would have happened if Roosevelt didn’t have his Brain Trust?

If Roosevelt had not said “The only thing we have to fear itself.” What do you think he would have stated to get his point across to the people?

Were there people that weren’t able to get help from the New Deal?

I notice the many different projects and legislations the New Deal had created. This kind of looks similar to the time when slavery end, and the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments were created. I feel like it’s similar because first of all, both of the things made were to help solve problems, such as slavery and the Homeless. Along with that, it is kind of like in a pattern, where slowly things got better and better.

If tenant farmers and sharecroppers did not receive government aid, how did they receive money or get by? Was it just from the crops or livestock that they sold?

Similar to how Hoover was blamed for the Great Depression, was FDR blamed for the cause of WWII?

What does Roosevelt mean when he stated, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself?”

When Roosevelt stated “The Only Thing We Have To Fear is Fear Itself’ he meant to tell the American people that their fear was making things worse. He was implying that it was their fear/terror that made the situation worse.