PRINT VERSION

JUMP TO

TRANSLATE

INTRODUCTION

The characters of Warner Brothers’ cartoon Anamaniacs once sang a song listing the presidents including the line “and then in 1929 the market crashes and we find, it’s Herbert Hoover’s big debut. He gets the blame and loses too!”

Poor President Hoover is the butt of so many jokes, and certainly was the source of much derision during his own four years in the White House. We tend of think of him as the president who saw the economy fail, and Franklin Roosevelt who defeated him in the election of 1932 as the one who guided the economy back to health. Like many things, this is an oversimplification. As historians, we can make closer inspection of what happened when the Depression was at its worst and form a more informed judgement of the 31st president and his legacy.

Does he deserve the mounds of criticism that have been heaped upon him? Did he create the Depression? Did he really fail to address the problem? Did he not care? Did he deserve to lose his bid for reelection?

What do you think?

A NEW REALITY

For most Americans, the crash affected daily life in myriad ways. In the immediate aftermath, there was a run on the banks, where citizens took their money out, if they could get it, and hid their savings under mattresses, in bookshelves, or anywhere else they felt was safe. Some went so far as to exchange their dollars for gold and ship it out of the country. A number of banks failed outright, and others, in their attempts to stay solvent, called in loans that people could not afford to repay. Working-class Americans saw their wages drop. Even Henry Ford, the champion of a high minimum wage, began lowering wages by as much as a dollar a day. Southern cotton planters paid workers only twenty cents for every one hundred pounds of cotton picked, meaning that the strongest picker might earn sixty cents for a fourteen-hour day of work. Governments struggled as well. When fewer citizens were earning money and paying taxes, elected leaders made hard decisions about how to spend the reduced tax revenues and laid off teachers and police officers.

The new hardships that people faced were not always immediately apparent. Many communities felt the changes but could not necessarily look out their windows and see anything different. Men who lost their jobs did not stand on street corners begging. They might be found keeping warm by a trashcan bonfire or picking through garbage at dawn, but mostly, they stayed out of public view. As the effects of the crash continued, however, the results became more evident. Those living in cities grew accustomed to seeing long breadlines of unemployed men waiting for a meal. Companies fired workers and tore down employee housing to avoid paying property taxes. The landscape of the country changed.

EFFECTS ON FAMILIES

The hardships of the Great Depression threw family life into disarray. Both marriage and birth rates declined in the 1930s. The most vulnerable members of society—children, women, minorities, and the working class—struggled the most. Parents often sent children out to beg for food at restaurants and stores to save themselves from the disgrace of begging. Many children dropped out of school, and even fewer went to college. In some cases, the schools and colleges themselves went bankrupt and closed. Childhood, as it had existed in the prosperous 20s, was over.

Families adapted by growing more in gardens, canning, and preserving, wasting little food if any. Home-sewn clothing became the norm as the decade progressed, as did creative methods of shoe repair with cardboard soles. Yet, one always knew of stories of the “other” families who suffered more, including those living in cardboard boxes or caves. By one estimate, as many as 200,000 children moved about the country as vagrants due to familial disintegration.

Women’s lives, too, were profoundly affected. Some wives and mothers sought employment to make ends meet, an undertaking that was often met with strong resistance from husbands and potential employers. Many men derided and criticized women who worked, feeling that jobs should go to unemployed men. Some campaigned to keep companies from hiring married women, and an increasing number of school districts expanded the long-held practice of banning the hiring of married female teachers. Despite the pushback, women entered the workforce in increasing numbers, from ten million at the start of the Depression to nearly thirteen million by the end of the 1930s. This increase took place in spite of the twenty-six states that passed a variety of laws to prohibit the employment of married women. Several women found employment in the emerging pink collar occupations, viewed as traditional women’s work, including jobs as telephone operators, social workers, and secretaries. Others took jobs as maids and housecleaners, working for those fortunate few who had maintained their wealth.

FARMERS

From the turn of the century through much of World War I, farmers in the Great Plains experienced prosperity due to unusually good growing conditions, high commodity prices, and generous government farming policies that led to a rush for land. As the federal government continued to purchase all excess produce for the war effort, farmers and ranchers fell into several bad practices, including mortgaging their farms and borrowing money against future production in order to expand. However, after the war, prosperity rapidly dwindled, particularly during the recession of 1921. Seeking to recoup their losses through economies of scale in which they would expand their production even further to take full advantage of their available land and machinery, farmers plowed under native grasses to plant acre after acre of wheat, with little regard for the long-term repercussions to the soil. Regardless of these misguided efforts, commodity prices continued to drop, finally plummeting in 1929, when the price of wheat dropped from two dollars to forty cents per bushel.

While factory workers may have lost their jobs and savings in the crash, many farmers also lost their homes, due to the thousands of farm foreclosures sought by desperate bankers. Between 1930 and 1935, nearly 750,000 family farms disappeared through foreclosure or bankruptcy. Even for those who managed to keep their farms, there was little market for their crops. Unemployed workers had less money to spend on food, and when they did purchase goods, the market excess had driven prices so low that farmers could barely piece together a living. A now-famous example of the farmer’s plight is that, when the price of coal began to exceed that of corn, farmers would simply burn corn to stay warm in the winter.

THE DUST BOWL

Exacerbating the problem was a massive drought that began in 1931 and lasted for eight terrible years. Dust storms roiled through the Great Plains, creating huge, choking clouds that piled up in doorways and filtered into homes through closed windows. Even more quickly than it had boomed, the land of agricultural opportunity went bust, due to widespread overproduction and overuse of the land, as well as to the harsh weather conditions that followed, resulting in the creation of the Dust Bowl. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

A great dust cloud rolls toward a farm. Storms of dust that were blown up in the Dust Bowl buried crops, equipment, animals, and even buildings. They were the result of poor farming practices and the resulting economic and ecological disaster drove thousands of farmers out of Oklahoma and the surrounding states.

Livestock died, or had to be sold, as there was no money for feed. Crops intended to feed the family withered and died in the drought. Terrifying dust storms became more and more frequent, as black blizzards of dirt blew across the landscape and created a new illness known as dust pneumonia. In 1935 alone, over 850 million tons of topsoil blew away. To put this number in perspective, geologists estimate that it takes the earth five hundred years to naturally regenerate one inch of topsoil. Yet, just one significant dust storm could destroy a similar amount. In their desperation to get more from the land, farmers had stripped it of the delicate balance that kept it healthy. Unaware of the consequences, they had moved away from beneficial techniques such as crop rotation in which different plants are grown on a field each year in order to avoid depleting nutrients. And worse of all, farmers had tried to maximize output by abandoning the practice of allowing land to regain its strength by permitting it to lie fallow between plantings, working the land to death.

For farmers, the results were catastrophic. Unlike most factory workers in the cities, in most cases, farmers lost their homes when they lost their livelihood. Most farms and ranches were originally mortgaged to small country banks that understood the dynamics of farming, but as these banks failed, they often sold rural mortgages to larger banks in the cities that were less concerned with the specifics of farm life. With the effects of the drought and low commodity prices, farmers could not pay their local banks, which in turn lacked funds to pay the large urban banks. Ultimately, the large banks foreclosed on the farms, swallowing up the small country banks in the process. It is worth noting that of the 5,000 banks that closed between 1930 and 1932, over 75% were country banks in locations with populations under 2,500. Given this dynamic, it is easy to see why farmers in the Great Plains remain wary of big city bankers even today. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

The great photographer Dorothea Lange captured this image of an Okie mother and her children during the Great Depression. It has become one of the enduring images of the era.

Even for farmers who survived the initial crash and avoided the devastation of the dust storms the situation continued to decline. Prices continued to fall, and as farmers tried to stay afloat, they produced still more crops, which increased the supply of food in the nation and with fewer consumers able to purchase an increasing supply, food prices collapsed. Farms failed at an astounding rate, and farmers sold out at rock-bottom prices. One farm in Shelby, Nebraska was mortgaged at $4,100 and sold for $49.50. One-fourth of the entire state of Mississippi was auctioned off in a single day at a foreclosure auction in April 1932.

Not all farmers tried to keep their land. Many, especially those who had arrived only recently, in an attempt to capitalize on the earlier prosperity, simply walked away. In hard-hit Oklahoma, thousands of farmers packed up what they could and walked or drove away from the land they thought would be their future. They, along with other displaced farmers from throughout the Great Plains, became known as Okies. Okies were an emblem of the failure of the American breadbasket to deliver on its promise, and their story was made famous in John Steinbeck’s novel, The Grapes of Wrath.

Many of the Okies drove to California along the famous Route 66. Once there, they worked on large farms for minimal pay and lived on the edges of the farms, and the edges of society, in shanty houses and camps without plumbing. Due to the lack of sanitation in the migrant camps, disease ran rampant.

AFRICAN AMERICANS

Most African Americans did not participate in the land boom and stock market speculation that preceded the crash, but that did not stop the effects of the Great Depression from hitting them particularly hard. Subject to continuing racial discrimination, African Americans nationwide fared even worse than their hard-hit White counterparts. As the prices for cotton and other agricultural products in the South plummeted, farm owners paid workers less or simply laid them off. Property owners evicted sharecroppers, and even those who owned their land outright had to abandon it when there was no way to earn any income.

In cities, African Americans fared no better. Unemployment was rampant, and many Whites felt that any available jobs belonged to Whites first. In some Northern cities, Whites would conspire to have African American workers fired to allow White workers access to their jobs. Even jobs traditionally held by African Americans, such as household servants or janitors, were given to Whites. By 1932, approximately one-half of all African Americans were unemployed.

Racial violence also began to rise. In the South, lynching became more common again, with 28 documented lynchings in 1933, compared to eight in 1932. Since communities were preoccupied with their own hardships, and organizing civil rights efforts was a long, difficult process, many resigned themselves to, or even ignored, this culture of racism and violence. Occasionally, however, an incident was notorious enough to gain national attention.

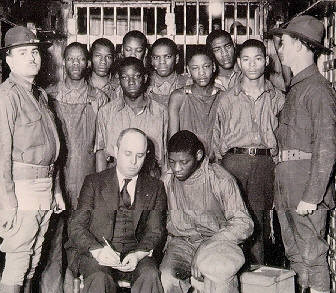

One such incident was the case of the Scottsboro Boys. In 1931, nine Black boys were arrested for vagrancy and disorderly conduct after an altercation with some White travelers on the train. Two young White women, who had been dressed as boys and traveling with a group of White boys, came forward and said that the Black boys had raped them. The case, which was tried in Scottsboro, Alabama, illuminated decades of racial hatred and illustrated the injustice of the court system. Despite evidence that the women had not been raped at all, along with one of the women subsequently recanting her testimony, the all-White jury convicted the boys and sentenced all but one of them to death. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

The Scottsboro Boys meet with one of their lawyers while in prison.

The verdict broke through the veil of indifference toward the plight of African Americans, and protests erupted among newspaper editors, academics, and social reformers in the North. The Communist Party of the United States offered to handle the case and sought retrial and the NAACP later joined in this effort. In all, the case was tried three separate times. The series of trials and retrials, appeals, and overturned convictions shone a spotlight on a justice system that provided poor legal counsel and relied on all-White juries. In 1932, the Supreme Court ruled in the case Powell v. Alabama that the defendants had been denied adequate legal representation at the original trial, and in 1935 in Patterson v. Alabama that due process as provided by the Fourteenth Amendment had been denied as a result of the exclusion of any potential Black jurors. Eventually, most of the accused received lengthy prison terms and subsequent parole, but avoided the death penalty. The Scottsboro case ultimately laid some of the early groundwork for the modern American civil rights movement. Alabama granted posthumous pardons to all defendants in 2013.

ORGANIZED LABOR

In 1932, a major strike at the Ford Motor Company factory near Detroit resulted in over sixty injuries and four deaths. Often referred to as the Ford Hunger March, the event unfolded as a planned demonstration among unemployed Ford workers who, to protest their desperate situation, marched nine miles from Detroit to the company’s River Rouge plant in Dearborn. At the Dearborn city limits, local police launched tear gas at the roughly 3,000 protestors, who responded by throwing stones and clods of dirt. When they finally reached the gates of the plant, protestors faced more police and firemen, as well as private security guards. As the firemen turned hoses on the protestors, the police and security guards opened fire. In addition to those killed and injured, police arrested 50 protestors. One week later, 60,000 mourners attended the public funerals of the four victims of what many protesters labeled police brutality. The event set the tone for worsening labor relations in the nation.

THE BONUS ARMY

Demonstrations grew in the nation’s capital as well, as Americans grew increasingly weary with President Hoover’s perceived inaction. The demonstration that drew the most national attention was the Bonus Army March of 1932.

In 1924, Congress rewarded veterans of World War I with certificates redeemable in 1945 for $1,000 each. By 1932, many of these former servicemen had lost their jobs and fortunes in the early days of the Depression. They asked Congress to redeem their bonus certificates early. Led by Walter Waters of Oregon, the so-called Bonus Expeditionary Force set out for the nation’s capital. Hitching rides, hopping trains, and hiking finally brought the Bonus Army, 15,000 strong, into the capital in June 1932 where President Hoover refused to meet them. Despite Hoover’s rejection of their demand, a debate began in the Congress over whether to fund the bonuses early.

As deliberation continued on Capitol Hill, the Bonus Army built a shantytown across the Potomac River in Anacostia Flats. When the Senate rejected their demands, most of the veterans dejectedly returned home. But several thousand remained in the capital with their families. Many had nowhere else to go. The Bonus Army conducted itself with decorum and spent their vigil unarmed. However, many believed them a threat to national security. On July 28, Washington police began to clear the demonstrators out of the capital. Two men were killed as tear gas and bayonets assailed the Bonus Marchers. Fearing rising disorder, Hoover ordered an army regiment into the city, under the leadership of General Douglas MacArthur. The army, complete with infantry, cavalry, and tanks, rolled into Anacostia Flats forcing the Bonus Army to flee. MacArthur then ordered the shanty settlements burned. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Part of the camp built by the Bonus Army marchers in Washington, DC. The camp was later cleared violently and burned by the army. The perceived callousness toward the veterans on the part of President Hoover helped destroy his chances for reelection.

Many Americans were outraged. How could the army treat veterans of the Great War with such disrespect? Hoover maintained that political agitators, anarchists, and communists dominated the mob. But facts contradict his claims. Nine out of ten Bonus Marchers were indeed veterans, and 20% were disabled. Despite the fact that the Bonus Army was the largest march on Washington up to that point in history, Hoover and MacArthur clearly overestimated the threat posed to national security. As Hoover campaigned for reelection that summer, the image of the president ordering the army to fight veterans haunted him.

THE HOMELESS

Millions of Americans were made homeless by the Great Depression. Of these, many wandered the country looking for work, often travelling by hopping on freight trains. These travelers were known as hobos. It is unclear exactly when hobos first appeared on the American railroading scene. With the end of the American Civil War in the 1860s, many discharged veterans returning home began hopping freight trains. Others looking for work on the American frontier followed the railways west aboard freight trains in the late 1800s. In any case, riding the rails was a well-established practice by the time the Great Depression started. Most frighteningly, 250,000 of the hobos during the Depression were teenagers.

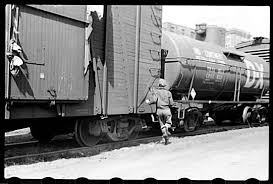

Life as a hobo was dangerous. In addition to the problems of being itinerant, poor, and far from home and support, plus the hostility of many train crews, they faced the railroads’ security staff, nicknamed bulls, who had a reputation for violence. Moreover, riding on a freight train was dangerous in and of itself. It was easy to be trapped between cars, fall, choke on smoke from the engines, overheat in summer or freeze in winter. At least 6,500 hobos died each year, either in conflicts with bulls or from accidents. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

A young boy runs to climb aboard a freight train as it pulls out of the yard.

CRIME

The Great Depression brought a rapid rise in the crime rate as many unemployed workers resorted to petty theft to put food on the table. Suicide rates rose, as did reported cases of malnutrition. Prostitution was on the rise as well. Alcoholism increased with Americans seeking outlets for escape, compounded by the repeal of prohibition in 1933. Cigar smoking became too expensive, so many Americans switched to cheaper cigarettes. In general, health care was not a priority for many Americans, as visiting the doctor was reserved for only the direst of circumstances.

HOOVER’S RESPONSE

In the immediate aftermath of Black Tuesday, Hoover sought to reassure Americans that all was well and reading his words after the fact, it is easy to laugh at how wrong he turned out to have been. In 1929 he said, “Any lack of confidence in the economic future or the strength of business in the United States is foolish.” In 1930, he stated, “The worst is behind us,” and in 1931, he pledged to provide federal aid should he ever witness starvation in the country.

Hoover was neither intentionally blind nor unsympathetic. He simply held fast to a belief system about the economy and the role of government that did not change as the realities of the Great Depression set in.

Hoover believed strongly in the ethos of American individualism: that hard work brought its own rewards. His life story testified to that belief. Hoover had been born into poverty, made his way through college at Stanford University, and eventually made his fortune as an engineer. This experience, as well as his extensive travels in China and throughout Europe, shaped his fundamental conviction that the very existence of American civilization depended upon the moral fiber of its citizens, as evidenced by their ability to overcome all hardships through individual effort and resolve. The idea of government directly intervening to help individual Americans was repellant to him. Whereas Europeans might need assistance, such as his hunger relief work in Belgium during and after World War I, he believed the American character to be different. In a 1931 radio address, he said, “The spread of government destroys initiative and thus destroys character.”

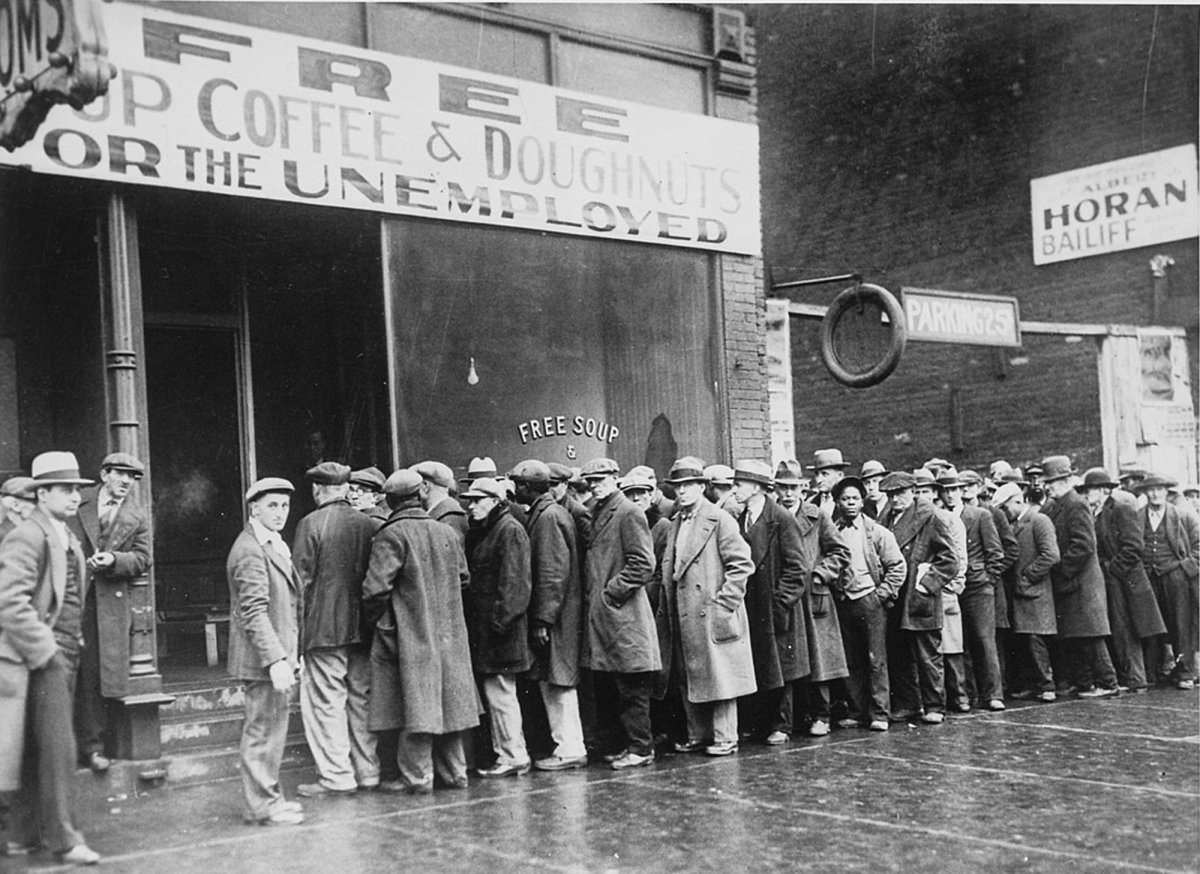

Likewise, Hoover was not completely unaware of the potential harm that wild stock speculation might create if left unchecked. As Secretary of Commerce, Hoover had repeatedly warned President Coolidge of the dangers that such speculation engendered. In the weeks before his inauguration, he offered many interviews to newspapers and magazines, urging Americans to curtail their rampant stock investments, and even encouraged the Federal Reserve to raise the discount rate to make it more costly for local banks to lend money to potential speculators. However, fearful of creating a panic, Hoover never issued a stern warning to discourage Americans from such investments. Neither Hoover, nor any other politician of that day, ever gave serious thought to using the power of government to regulate of the stock market. Staying out of other people’s business was a core belief that pervaded his work in government and his personal life as well. Hoover often lamented poor stock advice he had once offered to a friend. When the stock nose-dived, Hoover bought the shares from his friend to assuage his guilt, vowing never again to advise anyone on matters of investment. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Hungry men line up for free food. President Hoover preferred that charitable organizations address the problems of the Great Depression rather than spending government money.

In keeping with these principles, Hoover’s response to the crash focused on two very common American traditions. First, he asked individuals to tighten their belts and work harder, and second, he asked the business community to help sustain the economy by voluntarily retaining workers and continuing production. He summoned a conference of leading industrialists to meet in Washington, DC, urging them to maintain their current wages while America rode out this brief economic panic. The crash, he assured business leaders, was not part of a greater downturn and they had nothing to worry about. Similar meetings with utility companies and railroad executives elicited promises for billions of dollars in new construction projects, while labor leaders agreed to withhold demands for wage increases and workers continued to labor. Hoover also persuaded Congress to pass a $160 million tax cut to bolster American incomes, leading many to conclude that the president was doing all he could to stem the tide of the panic. In April 1930, the New York Times editorial board concluded that, “No one in his place could have done more.” It turned out that he could have done much more, since mostly he relied on a volunteerism in which he asked others to volunteer to make choices that would benefit the nation, rather than using the power of government, which he did lead.

Despite his best intentions, these modest steps were not enough. By late 1931, when it became clear that the economy would not improve on its own, Hoover recognized the need for some government intervention. He created the President’s Organization of Unemployment Relief (POUR). In keeping with Hoover’s distaste of what he viewed as handouts, this organization did not provide direct federal relief to people in need. Instead, it assisted state and private relief agencies, such as the Red Cross, Salvation Army, YMCA, and Community Chest. Hoover also strongly urged people with wealth to donate funds to help the poor, and he himself gave significant private donations to worthy causes.

Congress pushed for a more direct government response but Hoover refused to support any measure that gave direct relief. The president’s adamant opposition to direct-relief federal government programs should not be viewed as one of indifference or uncaring toward the suffering American people. His personal sympathy for those in need was boundless. Hoover was one of only two presidents to reject his salary for the office he held. Throughout the Great Depression, he donated an average of $25,000 annually to various relief organizations to assist in their efforts. Furthermore, he helped to raise $500,000 in private funds to support the White House Conference on Child Health and Welfare in 1930. Rather than indifference or heartlessness, Hoover’s steadfast adherence to a philosophy of individualism as the path toward long-term American recovery explained many of his policy decisions. “A voluntary deed,” he repeatedly commented, “is infinitely more precious to our national ideal and spirit than a thousand-fold poured from the Treasury.”

Unable to receive aid from the government, Americans thus turned to private charities such as churches, synagogues, and other religious organizations as well as aid from state governments. But these organizations were not prepared to deal with the scope of the problem. Private aid organizations were suffering along with everyone else. Since they relied on donations to fund their work and their donors were struggling as well, they did not have the funds to carry out the regular operations they had done during the good times of the 1920s, let along increase their services to provide for the enormous needs of the Depression.

Likewise, state governments were particularly ill-equipped. City governments had equally little to offer. In New York City in 1932, family welfare allowances were $2.39 per week, and only one-half of the families who qualified actually received them. In Detroit, allowances fell to fifteen cents a day per person, and eventually ran out completely as the city ran out of tax revenue to fund the program. In most cases, relief was only in the form of food and fuel. Charitable organizations provided nothing in the way of rent, shelter, medical care, clothing, or other necessities. There was no infrastructure to support the elderly, who were the most vulnerable, and this population largely depended on their adult children to support them, adding to families’ burdens.

During this time, local community groups, such as police and teachers, worked to help the neediest. New York City police, for example, began contributing 1% of their salaries to start a food fund that was intended to help those found starving on the streets. In 1932, New York City schoolteachers also joined forces to try to help. They contributed as much as $250,000 per month from their own salaries to help needy children. Chicago teachers did the same, feeding some 11,000 students out of their own pockets in 1931, despite the fact that many of them had not been paid a salary in months. These noble efforts, however, were scattered rather than comprehensive and failed to fully address the level of desperation that Americans everywhere were facing.

As conditions worsened, Hoover finally began to see the need for government action and formed the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) in 1932. Although not a form of direct relief to the American people in greatest need, the RFC was much larger in scope than any preceding effort, setting aside $2 billion in taxpayer money to rescue banks, credit unions, and insurance companies. The goal was to boost confidence in the nation’s financial institutions by ensuring that they were on solid footing. This model was flawed on a number of levels. First, the program only lent money to banks with sufficient collateral, which meant that most of the aid went to large banks. In fact, of the first $61 million loaned, $41 million went to just three banks. Small town and rural banks got almost nothing. Furthermore, at this time, confidence in financial institutions was not the primary concern of most Americans. They needed food and jobs. Many had no money to put into the banks, no matter how confident they were that the banks were safe.

ESCAPE TO THE MOVIES

In the decades before the Great Depression, and particularly in the 1920s, American culture largely reflected the values of individualism, self-reliance, and material success through competition. Novels like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Sinclair Lewis’s Babbit portrayed wealth and the self-made man in America. The rags-to-riches fable that Americans so loved was also a key feature in silent movies such as Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush. It would seem that with so little money to spend, Americans would skip the added expense of the movies, but this turned out not to be the case. While box office sales briefly declined at the beginning of the Depression, they rebounded. Movies offered a way for Americans to think of better times, and people were willing to pay twenty-five cents for a chance to escape, at least for a few hours. And, with the shift in fortunes, came a shift in values. During the Great Depression, movies revealed an emphasis on the welfare of the whole and the importance of community in preserving family life.

Even the songs found in films reminded many viewers of the bygone days of prosperity and happiness, from Al Dubin and Henry Warren’s hit “We’re in the Money” to the popular “Happy Days are Here Again.” The latter eventually became the theme song of Franklin Roosevelt’s 1932 presidential campaign. People wanted to forget their worries and enjoy the madcap antics of the Marx Brothers, the youthful charm of Shirley Temple, the dazzling dances of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, or the comforting morals of the Andy Hardy series. The Hardy series—nine films in all, produced by MGM from 1936 to 1940—starred Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney, and all followed the adventures of a small-town judge and his son. No matter what the challenge, it was never so big that it could not be solved with a musical production put on by the neighborhood kids, bringing together friends and family members in a warm display of community values. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Judy Garland stared as Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz. The 1939 movie tells the story of a girl transported to the mythical land of Oz and her quest to return home. Many movie who watched it understood it as an allegory for the nation’s journey through the Great Depression.

All of these movies reinforced traditional American values, which suffered during these hard times, in part due to declining marriage and birth rates, and increased domestic violence. At the same time, however, they reflected an increased interest in sex and sexuality. While the birth rate was dropping, surveys in Fortune magazine in 1936–1937 found that two-thirds of college students favored birth control, and that 50% of men and 25% of women admitted to premarital sex, continuing a trend among younger Americans that had begun to emerge in the 1920s.

THE ELECTION OF 1932

Undoubtedly, the fault of the Great Depression was not Hoover’s. But as the years of his Presidency passed and the country slipped deeper and deeper into its quagmire, he would receive great blame. Urban shantytowns were dubbed Hoovervilles. Newspapers used by the destitute as bundling for warmth became known as Hoover blankets. Pockets turned inside out were called Hoover flags. Somebody had to be blamed, and many Americans blamed their President. Running for President under the slogan “Rugged Individualism” made it difficult for Hoover to promote massive government intervention in the economy.

In 1930, succumbing to pressure from American industrialists, Hoover signed the Hawley-Smoot Tariff which was designed to protect American industry from overseas competition by adding a tax to imported goods. The theory was that the tax would make foreign-made products more expensive and people would then buy things made in America. Passed against the advice of nearly every prominent economist of the time, it was the largest tariff in American history. The Hawley-Smoot Tariff proved to be a disaster. Instead of helping American manufacturers, it hurt them when other nations responded with tariffs of their own. As foreign markets for American-made products dried up, the entire world suffered from a slowdown in global trade.

Nearly anyone could have beaten Hoover in the 1932 presidential election. New York Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt won the Democratic nomination promising “a new deal for the American people” that included a repeal of prohibition. The Republicans renominated Hoover, perhaps because there were few other interested GOP candidates.

Roosevelt was born in 1882 to a wealthy New York industrialist. The fifth cousin of Theodore Roosevelt, FDR became involved in politics at a young age. A strong supporter of Woodrow Wilson and the League of Nations, Roosevelt was the unsuccessful Democratic candidate for Vice-President in 1920. The following year he contracted polio, and although he survived the deadly illness, like many other Americans who suffered from the dreaded disease, he could never walk without crutches again.

Election day brought a landslide for the Democrats, as Roosevelt earned 58% of the popular vote and 89% of the electoral vote, handing the Republicans their second-worst defeat in their history. Bands across America struck up Roosevelt’s theme song “Happy Days Are Here Again” as millions of Americans looked with hope toward their new leader.

CONCLUSION

The Great Depression was certainly terrible, but it was also not the fault of any one person, so it is unfair to blame the president who happened to be sitting in the Oval Office at the time for creating the problem.

It is altogether appropriate, however, to consider his performance in office in terms of the way he addressed the problem. Every president deals with unexpected problems, and although Hoover probably found himself in one of the worst positions of any president, it was still his responsibility to help guide the nation back to health. Did he do this? Was his approach correct? Did it work? Did he fail to care, or care enough?

In 1932, voters resoundingly rejected his leadership and looked to Roosevelt for something different. Looking back from the distance of nearly a century, what do you think? Did Hoover deserve the electoral drumming he endured? Did he deserve to lose?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The Great Depression was the worst economic disaster in the nation’s history and life was hard for all Americans, especially minorities. In the end, people turned to Franklin Roosevelt who promised new ideas.

The Great Depression affected everyone. Even people who did not lose their jobs usually had their pay lowered. Hungry, jobless, homeless people became a common sight on the streets of American cities. Even the government struggled. With fewer people working, fewer people were paying taxes, and politicians struggled with hard decisions about how to solve the crisis.

Farmers who had bad loans from the 1920s lost their farms as banks foreclosed. In the middle of the country, a drought and poor farming techniques combined to form the Dust Bowl. People whose farms had been ruined by the dust fled to California and elsewhere looking for a chance to start over.

The Depression was especially hard for African Americans. The few jobs that were available were given to Whites first. In some places, anger and frustration boiled over and African Americans were targeted. Lynching increased. In one famous case, the Scottsboro Boys were tried for a crime that never happened. The experience of surviving the Great Depression inspired African Americans to begin the community organizing necessary for the later Civil Rights Movement.

Organized labor suffered during the Depression. In Detroit, hungry workers marched to a Ford factory and clashed violently with police.

Millions of Americans were left homeless. Many rode the rails looking for work. Among these, tens of thousands were teenagers. It was a dangerous life.

Families were hit especially hard. Divorce and separation increased. Birth rates fell. More women began looking for work in order to support their families. Many children dropped out of school.

During the Depression, Americans loved going to the movies. It was a chance to escape the hardships of daily life.

President Hoover tried to address the crisis by encouraging businesses not to raise prices or lower wages. In order to help the millions who were suffering, he encouraged churches and other civil groups to operate shelters and soup kitchens. This failed to solve the problem, simply because the problem was so large.

In Washington, DC, an army of World War I veterans gathered to demand early payment of a bonus. President Hoover ordered their camp cleared. It was a decision that cemented his unpopularity.

In 1932, Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt won the presidential election. He promised voters a new deal.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Okies: Families of farmers who fled the Dust Bowl during the Great Depression. Many went to California.

John Steinbeck: Author of The Grapes of Wrath which chronicled the plight of Okies during the Great Depression.

Scottsboro Boys: Group of nine African Americans who were accused of rape during the Great Depression. They were convicted but a series of appeals brought attention to injustices in the southern court system.

Bonus Army: Group of World War I veterans who travelled to Washington, DC during the Great Depression where the set up a temporary camp. They were demanding early payment of a bonus promised to them by congress, but were eventually evicted forcibly by the army.

Douglas MacArthur: American general who led the clearing of the Bonus Army camp during the Great Depression and went on to be a celebrated commander in the Pacific Theater during World War Two.

Hobos: Homeless people who rode freight trains during the Great Depression.

Marx Brothers: Comedians during the Great Depression.

Shirley Temple: Child movie star during the Great Depression. Her curly hair and cheery demeanor made her popular with people looking for an escape from their troubles.

Fred Astaire: Movie star and dancer during the Great Depression. He is famous for his routines with Ginger Rogers.

Ginger Rogers: Movie star and dancer during the Great Depression. She is famous for her routines with Fred Astaire.

Judy Garland: Movie star during the Great Depression. She is famous for playing Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz.

Mickey Rooney: Movie star during the Great Depression. His career stretched over many decades beginning in the silent film era.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt: American president first elected during the Great Depression. He promised a New Deal and went on to be elected a total of four times. He led the nation through most of World War II.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Crop Rotation: A farming practice in which fields are planted with different plants each season in order to prevent total loss of needed nutrients.

Lie Fallow: A farming practice in which a field is allowed to go unused during a season in order for nutrients to be replenished.

Riding the Rails: Illegally hitching a ride of a freight train. This common practice during the Great Depression.

![]()

GOVERNMENT AGENCIES

Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC): Government agency set up under the Hoover Administration that provided funding to support troubled banks in an effort to prevent bank failures.

![]()

COURT CASES

Powell v. Alabama: A Supreme Court case in which the Scottsboro Boys argued that they had received inadequate legal representation in their trial.

Patterson v. Alabama: A Supreme Court case in which the Scottsboro Boys argued that their trial was unjust because all African American jurors had been excluded.

![]()

TEXTS

The Grapes of Wrath: Book by John Steinbeck which chronicled the plight of Okies during the Great Depression.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Dust Bowl: Area around Oklahoma in the early-1930s that suffered a devastating drought. The effects were exacerbated by poor farming practices that resulted in a catastrophic loss of topsoil and the exodus of many farm families.

Hooverville: Nickname for the homeless camps that developed in many large cities during the Great Depression.

![]()

EVENTS

Ford Hunger March: 1932 strike and march in Detroit by Ford workers that resulted in a confrontation with police and the deaths of four marchers.

![]()

POLICIES & LAWS

Volunteerism: President Hoover’s plan to deal with the Great Depression. He wanted private companies and organizations to provide help to the needy and continue to employ workers on their own.

Hawley-Smoot Tariff: Tariff law passed during the Hoover Administration during the Great Depression. It raised taxes on imports in an effort to help American manufactures. In retaliation, other nations also raised tariffs and American exporters suffered leading to a worsening of the Depression.

https://www.history.com/topics/great-depression/scottsboro-boys (More information about the Scottsboro Boys)

Was there an increase rate of death in farmers when the dust bowl took place?

Like how themes in popular media shifted to wealth, hope, and the better days as an escape during the Great Depression, are there similar shifts in themes for today’s media due to Covid?

What was the birthrate-death ratio during the Great Depression.

How are farmers today affected from the farmers in the past and how badly will another dust bowl be?

Other than forming private relief organizations, did Hoover take any other health-related actions?

Given that Hoover had made a lot of decisions that the citizens didn’t like, he didn’t seem to have any new ideas, and a lot of people blamed him for the Depression, why did the Republicans decide to put him up for reelection anyway?

If I was living during this time, as a struggling US citizen, I would be very mad at Hoovers approach to the Depression because it seemed like he cared about how bad Americans were struggling to just survive. Instead, he just saw the issue as a market crash and a slow economy.

Are there people in today’s society that believed Hoover caused the Great Depression?

What could Hoover have done differently to win the election of 1932?

Why did President Hoover hate direct government relief ?

Since President Hoover believed in American Individualism, would he also have supported Booker T. Washington’s Atlanta Compromise?

Was the panic that Hoover dreaded on if he were to warn Americans about stocks worth it to help lessen the depression?

How different would it be if Hoover did a better job? Would he have been reelected?

What do you think the punishment for the Scottsboro Boys would’ve been like today?

If President Hoover had relied on using volunteerism in which he asked others to volunteer to make choices that would benefit the nation, then why did he not listen to the people who told him to provide direct relief using the power of the government?

Why did the farmers keep on growing more and more resources that they couldn’t sell? If the demand was low, why did they keep on making the supply higher and higher?

I can’t help but wonder if Hoover’s perspective on how to solve the crisis of the Great Depression had an upper hand. I find it peculiar that he left little assistance to the people while making the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to just help large banks. He held off an intervention for a long time and did so without giving in to the mass public’s needs! Is this a sign of corruption?

How was Hoover able to come up with his poor stock advice?

What other movies were showcased during the Great Depression besides the ones mentioned in the text?

Why did they blame the president when the Great Depression even though no one was at fault?

I guess considering he was president and that his job is to help his people, he did poorly with it. He had poor ideas and responses to the Great Depression which led to his downfall

Were the Okies similar to the slaves who had fled to the North during slavery? I would say maybe because both groups are fleeing to try and find a better place, but they are doing it for different reasons.

A lot of immigrants were moving to the United States for a better life and job opportunities, so during the great depression, did they try to go back to their country? Did the number of immigrants decrease during the great depression

you’d think it would be at a decrease due to the events happening. here’s an article to read more about it: https://immigrationtounitedstates.org/527-great-depression.html

Were the farmers who actually tried to keep their land or farms eventually forced to leave, due to the hard circumstances they had to face?

Why were they named the “Scottsboro” boys?

The original case/trial took place in Scottsboro, Alabama. The boys got the name as a nickname during their trials.

Why did Hoover decide to get involved with stock investments and the Federal Reserve?