INTRODUCTION

There is no one alive today who was born before American politics was dominated by two great parties: the Republicans and Democrats. They are such a part of our lives that few can imagine a time before they existed. And yet, they haven’t always been our two parties. In fact, we have not always had two parties.

Having two political parties is actually unusual in the world. Many countries operate with multiple parties who team up to form coalitions. In other places, there is just one party, and all political debates are held between members of a single party.

But the United States has a two-party system.

Where did this come from? Why two parties? What were the first two parties? Did we have to have parties at all?

Why can’t we all just be American?

HAMILTON’S FINANCIAL PLAN

The first federal government under newly elected President Washington faced numerous challenges, including how to deal with the financial chaos created by the American Revolution. States had huge war debts. There was runaway inflation. Almost all areas of the economy looked dismal throughout the 1780s. Economic hard times were a major factor creating the sense of crisis that had prompted the creation of the stronger central government under the new Constitution.

George Washington chose the talented Alexander Hamilton, who had served with him throughout the Revolutionary War, to take on the challenge of directing federal economic policy as the treasury secretary. Hamilton is a fascinating character whose ambition fueled tremendous success as a self-made man. Born in the West Indies to a single mother who was a shopkeeper, he learned his first economic principles from her and went on to apprentice for a large mercantile firm. From these modest origins, Hamilton went on to become the foremost advocate for a modern capitalist economy in the early national United States.

The first issue that Hamilton tackled as Washington’s Secretary of the Treasury concerned the problem of public credit. Governments at all levels had taken on debt during the Revolution. The commitment to pay back creditors had not been taken seriously by some of the states. By the late 1780s, the value of such public securities had plunged to a small fraction of their face value. In other words, state IOUs, the money borrowed to finance the Revolution, were viewed as nearly worthless.

If the government would not pay back loans, no one would loan the government money. Even today, savings bonds are an essential way that the government raises money. Savings bonds are considered a good investment now because we trust that the government will pay them back. However, in the 1780s, almost no one had faith in the state governments’ willingness to pay off their loans.

Hamilton issued a bold proposal. The federal government should pay off all state debts at full value. Such action would dramatically enhance the legitimacy of the new central government. To raise money to pay off the debts, Hamilton would issue new securities, or bonds. Investors who purchased these new public securities could make enormous profits when the time came for the United States to pay off these new debts.

Hamilton’s vision for reshaping the American economy included a federal charter for a national financial institution. He proposed a Bank of the United States. Modeled along the lines of the Bank of England, a central bank would help make the new nation’s economy dynamic. At the time, banks could print their own money. By creating a large, stable bank that people trusted, the economy could thrive with a stable paper currency.

The central bank faced significant opposition. Many feared it would fall under the influence of wealthy, urban Northeasterners and speculators from overseas. In the end, with the support of George Washington, the bank was chartered with its first headquarters in Philadelphia.

The third major area of Hamilton’s economic plan aimed to make American manufacturers self-sufficient. The American economy had traditionally rested upon large-scale agricultural exports to pay for the import of British manufactured goods. Hamilton rightly thought that this dependence on expensive foreign goods kept the American economy at a limited level, especially when compared to the rapid growth of early industrialization in Great Britain.

Rather than accept this condition, Hamilton wanted the United States to adopt a mercantilist economic policy. This would protect American manufacturers through direct government subsidies and tariffs. By helping American manufacturers by giving them government money and protecting them from imports by increasing the price of imported goods by adding tariffs, local producers could stand a chance. This protectionist policy would help fledgling American producers to compete with inexpensive European imports. Secondary Source: Banknote

Secondary Source: Banknote

Alexander Hamilton’s role in stabilizing the economy is honored on the $10 bill. The Department of the Treasury Building in Washington, DC is on the back of the bill.

Hamilton possessed a remarkably acute economic vision. His aggressive support for manufacturing, banks, and strong public credit all became central aspects of the modern capitalist economy that would develop in the United States in the century after his death. Nevertheless, his policies were deeply controversial in their day.

Many Americans neither like Hamilton’s elitist attitude nor his commitment to a British model of economic development. His pro-British foreign policy was potentially explosive in the wake of the Revolution. Hamilton favored an even stronger central government than the Constitution had created and often linked democratic impulses with potential anarchy. Finally, because the beneficiaries of his innovative economic policies were concentrated in the northeast, they threatened to stimulate divisive geographic differences in the new nation.

Regardless, with the support of President Washington, Hamilton’s economic philosophies became touchstones of the modern American capitalist economy.

Thomas Jefferson, who was the secretary of state at the time, thought Hamilton’s plans for full payment of the public debt stood to benefit a “corrupt squadron of paper dealers.” To Jefferson, speculation in paper certificates threatened the virtue of the new American Republic. In his mind, what was valuable was land and the yeoman farmers who worked the land. Even Madison, who had worked closely with Hamilton in co-authoring The Federalist Papers, thought the public debt repayment plan gave too big a windfall to wealthy financiers.

There was a significant political element to Hamilton’s proposal. Many of the poor farmers who had purchased the state securities during the Revolution had sold them as they lost value. Wealthy investors purchased these securities at rock bottom prices. If Hamilton was going to pay off the debts at face value, the investors stood to make a handsome profit while the farmers and artisans would feel cheated. Once again it appeared that Hamilton was willing to help enrich his banker friends at the expense of the average American.

As a counter-measure Madison proposed that Congress should set aside some money for the original owners of the debts, the ordinary Americans and not new investors and speculators.

On a pragmatic level Madison’s idea would have been difficult to implement. It would be hard to know who the bonds first belonged to, and furthermore, nearly half the members of Congress were wealthy and had invested in public securities. They stood to benefit financially from Hamilton’s plan. Its passage was doubly assured.

Hamilton’s successful bid to charter a national Bank of the United States also brought strong opposition from Jefferson. Their disagreement about the bank stemmed from sharply opposed interpretations of the Constitution. For Jefferson, such action was clearly beyond the powers granted to the federal government. In his strict interpretation of the Constitution, Jefferson pointed out that the 10th Amendment required that all federal authority be expressly stated in the law. Nowhere did the Constitution allow for the federal government to create a bank.

Hamilton responded with a loose interpretation that allowed such federal action under a clause permitting Congress to make “all Laws which shall be necessary and proper.”

Neither side was absolutely right. The Constitution needed interpretation. In this difference, however, we can see sharply contrasting visions for the future of the republic.

Opposition to Hamilton’s financial policies spread beyond the cabinet. The legislature divided about whether or not to support the Bank of the United States. This split in Congress loomed as a potential threat to the Union because northern representatives overwhelmingly voted favorably, while southerners were strongly opposed. The difference stemmed from significant economic differences between the sections. Large cities, merchants, and leading financiers were much more numerous in the North and stood to benefit from Hamilton’s plans.

Keen observers began to fear that sharp sectional differences might soon threaten the Union. Indeed, the Bank ultimately found support in Congress through a compromise that included a commitment to build the new federal capital on the banks of the Potomac River in the South. In part, this stemmed from the fact that southern states such as Virginia had already paid off their war debt and stood to gain nothing from a central bank. While most of the commercial beneficiaries of Hamilton’s policies were concentrated in the urban Northeast, the political capital of Washington, DC would stand in the more agricultural South. By dividing the centers of economic and political power many hoped to avoid a dangerous concentration of power in any one place or region.

The increasing discord of the early 1790s pointed toward an uncertain future. The Virginian Jefferson and the New Yorker Hamilton serve as useful figureheads for the opposing sides. While Hamilton was an adamant elitist whose policies favored merchants and financiers, Jefferson, though wealthy, favored policies aimed toward ordinary farmers.

Their differences also extended to the branch of government that each favored. Hamilton thought a strong executive and a judiciary protected from direct popular influence were essential to the health of the republic. By contrast, Jefferson put much greater faith in democracy and felt that the truest expression of republican principles would come through the legislature, which was elected directly by the people. Their differences would become even sharper as the decade wore on.

THE NEW NATIONAL CAPITAL

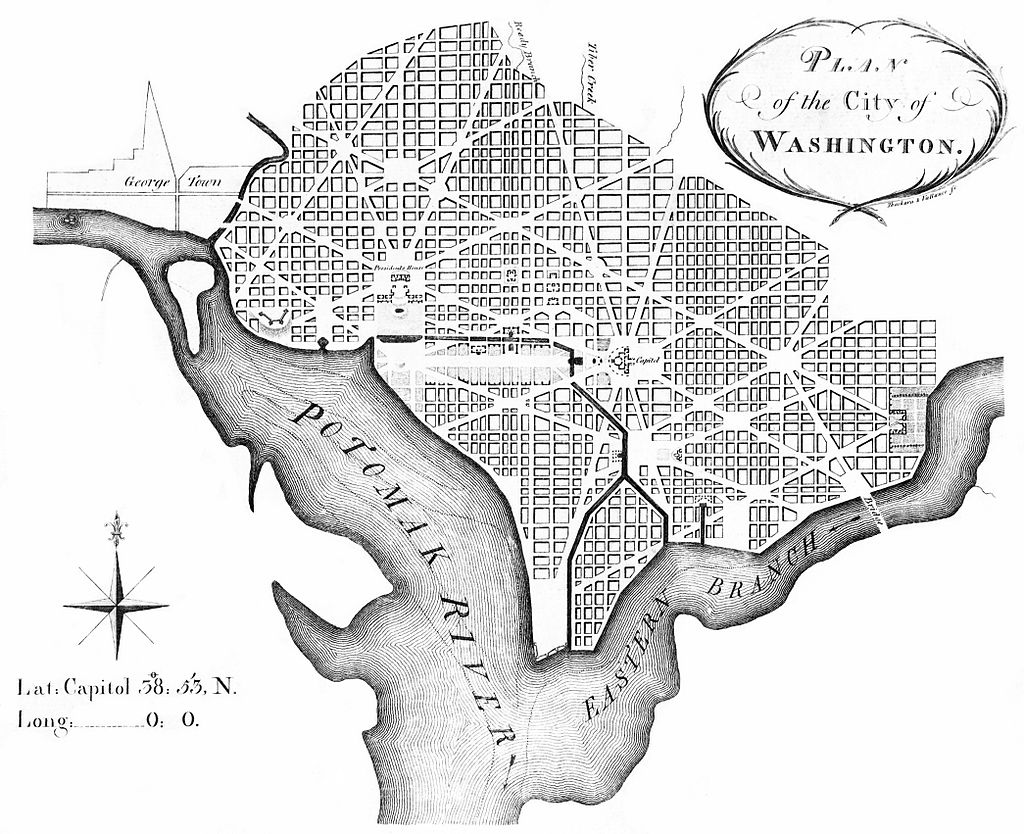

Focusing on how the capital city of the federal government changed in the early years of the nation reminds us of the limited nature of the early central government. Like so many other elements of the new nation, even the most basic features of the capital city were unsettled. President Washington first took office in New York City, but, when reelected in 1792, the capital had already moved to Philadelphia where it would remain for a decade. Fittingly, Jefferson was the first president to be inaugurated in the new and lasting capital of Washington, DC. Primary Source: Map

Primary Source: Map

L’Enfant’s original plan for Washington. Unlike the modern city, L’Enfant envisioned canals running through the center of the city to carry merchant traffic. The city never became the bustling economic metropolis he and George Washington hoped it would, but it is one of the largest cities in America, due mostly to the enormous size and importance of the federal government.

The site of the new capital was the product of political compromise. As part of the struggle over Hamilton’s financial policy, Congress supported the Bank of the United States, which would be headquartered in Philadelphia. In exchange, the special District of Columbia, to be under Congressional control, would be built on the Potomac River. The compromise represented a symbolic politics of the very highest order. While Hamilton’s policies encouraged the consolidation of economic power in the hands of bankers, financiers, and merchants who predominated in the urban northeast, the political capital was to be in a more southerly and agricultural region apart from those economic elites.

Once the site for the new capital was selected in 1790, President Washington retained Pierre Charles L’Enfant, a French engineer and former officer in the Continental Army, to design and lay out the new capital city. His grand plan gave pride of place to the capitol building which would stand on a hill overlooking the flatlands around the Potomac. A long open mall connected the legislative building to the river and was to be bordered by varied stately buildings. Radiating out from the capital were broad avenues one of which would connect with the president’s house. Much of L’Enfant’s grand vision was ignored during the 1800s, but starting in 1901 the plan was vigorously reborn.

Today, Washington, DC, is an impressive capital city that physically expresses the central values of the modern United States. It gloriously honors the nation’s commitment to democracy and political life in impressive government buildings. The capital also maintains the nation’s historical memory in monuments along the mall that commemorate key events and people. The city also announces the nation’s commitment to knowledge and human achievement in the spectacular Smithsonian museums. At the same time the capital also symbolizes less celebrated aspects of modern America. Washington, DC’s impressive center around the mall is surrounded by urban poverty, a crisis facing most large American cities. The gulf separating American success and failure is on display nowhere more sharply.

Today’s Washington, DC, however, is a far cry from the humble place that Jefferson entered in 1801. Then just beginning to emerge from a swampy location along the Potomac, the city claimed only 5,000 inhabitants, many of them temporary residents to serve the incoming politicians. The Senate building had been completed, but the building for the House of Representatives was still incomplete as was the president’s house.

On Saturday, November 1, 1800, John Adams became the first president to take residence in the building. During Adams’ second day in the house, he wrote a letter to his wife Abigail, containing a prayer for the house. Adams wrote, “I pray Heaven to bestow the best of blessings on this House, and all that shall hereafter inhabit it. May none but honest and wise men ever rule under this roof.” Americans may judge for themselves whether or not Adams’ prayer has come true.

The limited physical stature of the new capital city matched the modest scope of the federal government, which only included 130 officials in the days of the early republic. In fact, with the exception of the postal service, the national government provided almost no services that reached ordinary people in their everyday lives. For most people in the early republic, meaningful political decisions were made at the state and local level.

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

The French Revolution brought fundamental changes to the feudal order of monarchical and aristocratic privilege. Americans widely celebrated the French Revolution in its glorious opening in 1789, as it struck at the very heart of absolutist power. France seemed to be following the American republican example by creating a constitutional monarchy where traditional elites would be restrained by written law. Where the king had previously held absolute power, now he would have to act within clear legal boundaries.

The French Revolution soon moved beyond this already considerable assault on the traditional order. Pushed forward by a crisis brought on by war that began with Prussia and Austria, the French Revolution took a dramatic turn that climaxed with the beheading of King Louis XVI and the abandonment of Christianity in favor of a new state religion based on reason. The French Revolution became far more radical than the American Revolution. In addition to a period of extreme public violence, which became known as the Reign Of Terror, the French Revolution also attempted to enhance the rights and power of poor people and women. In fact, it even went so far as to outlaw slavery in the French colonies of the Caribbean.

The profound changes set in motion by the French Revolution had an enormous impact in France as well as through the large scale European war it sparked from 1792 to 1815. It also helped to transform American politics. While the French Revolution had initially received broad support in the United States, its radicalization led to sharp disagreement in American opinion. Primary Source: Painting

Primary Source: Painting

The French Revolution took a dark turn when the leaders of the Revolution began executing people in large numbers. Their preferred method was the Guillotine, which promised to be both quick and painless. Alas, the public spectacle also made the method a form of terror.

Domestic attitudes toward the proper future of the American republic grew even more intense as a result of the example of revolutionary France. Hamilton, Washington, and likeminded men who would soon organize as the Federalist Party saw the French Revolution as an example of homicidal anarchy. When Great Britain joined European allies in the war against France in 1793, Federalists supported this action as an attempt to enforce proper order.

The opposing American view, held by men like Jefferson, Madison and others who came to organize as the Democratic-Republican political party, supported French actions as an extension of a world-wide republican struggle against corrupt monarchy and aristocratic privilege. For example, some groups among the Whiskey Rebels in western Pennsylvania demonstrated their international vision when they rallied beneath a banner that copied the radical French slogan of “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité.”

The example of the French Revolution helped convince Americans on both sides that their political opponents were motivated by dangerous and even evil forces that threatened to destroy the young republic. Hamilton saw the chaos of the Reign of Terror as a warning to Americans. In his view, order imposed by a strong central government would prevent the worst excesses of the masses from destroying the nation. For Madison and Jefferson, the French Revolution symbolized the power of individuals in their quest for personal liberty against the tyrannical power of an absolute monarch.

TWO PARTIES EMERGE

The election of 1796 was the first election in American history where political candidates at the local, state, and national level began to run for office as members of organized political parties that held strongly opposed political principles.

This was a stunning new phenomenon that shocked most of the older leaders of the Revolutionary Era. Even Madison, who was one of the earliest to see the value of political parties, believed that they would only serve as temporary coalitions for specific controversial elections. The older leaders failed to understand the new conditions that had been created by the American Revolution. As the Preamble to the Constitution had clearly pointed out, “The People” now understood themselves as a fundamental force in legitimating government authority. In the modern American political system, voters mainly express themselves through allegiances within a competitive party system. 1796 was the first election where this defining element of modern political life began to appear.

The two parties adopted names that reflected their most cherished values. The Federalists of 1796 attached themselves to the successful campaign in favor of the Constitution and were solid supporters of the federal administration. Although Washington denounced parties as a horrid threat to the republic and tried to remain a unifying symbol of all Americans above the influence of parties, his vice president John Adams became the de facto presidential candidate of the Federalists. The party had its strongest support among those who favored Hamilton’s policies. Merchants, creditors and urban artisans who built the growing commercial economy of the Northeast provided its most dedicated supporters.

The opposition party adopted the name Democratic-Republicans, which suggested that they were more fully committed to extending the Revolution to ordinary people. The supporters of the Democratic-Republicans, often referred to as the Republicans (not to be confused with modern Republicans), were drawn from many segments of American society, especially farmers. The Democratic-Republicans enjoyed high popularity among German and Scots-Irish ethnic groups. Although it effectively reached ordinary citizens, its key leaders were wealthy southern tobacco elites like Jefferson and Madison. While the Democratic-Republicans were more diverse, the Federalists were wealthier and carried more prestige, especially by association with the retired Washington.

The 1796 election was waged with uncommon intensity. Federalists thought of themselves as the “friends of order” and good government. They viewed their opponents as dangerous radicals who would bring the anarchy of the French Revolution to America. The Democratic-Republicans despised Federalist policies. According to one Republican-minded New York newspaper, the Federalists were “aristocrats, endeavoring to lay the foundations of monarchical government, and Republicans [were] the real supporters of independence, friends to equal rights, and warm advocates of free elective government.” Clearly there was little room for compromise in this hostile environment.

The outcome of the presidential election indicated the close balance between the two sides. New England strongly favored Adams, while Jefferson overwhelmingly carried the southern states. The key to the election lay in the mid-Atlantic colonies where party organizations were the most fully developed. Adams ended up narrowly winning in the electoral college 71 to 68. A sure sign of the great novelty of political parties was that the Constitution had established that the runner-up in the presidential election would become the vice president.

John Adams took office after a harsh campaign and narrow victory. His political opponent Jefferson served as the new vice president.

THE ADAMS PRESIDENCY

The Adams administration faced several tests. It was a mixed administration. Adams was a Federalist. Jefferson, the vice-president, was a Democratic-Republican. Federalists were increasingly divided between conservatives such as Hamilton and moderates such as Adams who still saw himself as above party politics. Hamilton had opposed Adams as the Federalist candidate. This helped create the circumstances whereby Jefferson slipped past the Federalist candidate, Thomas Pinckney, to become vice president Although Hamilton resigned from the cabinet in 1795, he remained influential and his advice was sought and followed by many Federalists, even some who remained in Adams’ cabinet.

During his presidency, France began harassing American merchant ships who were doing business with Britain. Adams took strong steps in response including severe repression of domestic protests. A series of laws known collectively as the Alien and Sedition Acts were passed by the Federalist Congress in 1798 and signed into law by President Adams. These laws included new powers to deport foreigners as well as making it harder for new immigrants to vote. Previously a new immigrant would have to reside in the United States for five years before becoming eligible to vote, but a new law raised this to 14 years.

Clearly, the Federalists saw foreigners as a deep threat to American security. As one Federalist in Congress declared, there was no need to “invite hordes of Wild Irishmen, nor the turbulent and disorderly of all the world, to come here with a basic view to distract our tranquility.” Not coincidentally, non-English ethnic groups had been among the core supporters of the Democratic-Republicans in 1796.

The most controversial of the new laws permitting strong government control over individual actions was the Sedition Act. In essence, this Act prohibited public opposition to the government. Fines and imprisonment could be used against those who “write, print, utter, or publish… any false, scandalous and malicious writing” against the government.

Under the terms of this law over 20 Republican newspaper editors were arrested and some were imprisoned. The most dramatic victim of the law was Representative Matthew Lyon of Vermont. His letter that criticized President Adams’ “unbounded thirst for ridiculous pomp, foolish adulation, and self avarice” caused him to be imprisoned. While Federalists sent Lyon to prison for his opinions, his constituents reelected him to Congress even from his jail cell.

The Sedition Act clearly violated individual protections under the First Amendment’s protect of freedom of speech. However, the practice of judicial review, whereby the Supreme Court considers the constitutionality of laws was not yet well developed. Furthermore, the justices were all strong Federalists having been appointed by George Washington. As a result, Madison and Jefferson directed their opposition to the new laws to state legislatures. The Virginia and Kentucky legislatures passed resolutions declaring the federal laws invalid within their states. The bold challenge to the federal government offered by this strong states’ rights position seemed to point toward imminent armed conflict within the United States.

Federalists in government now viewed the persistence of their party as the equivalent of the survival of the republic. This led them to enact and enforce harsh laws. Madison, who had been the chief architect of a strong central government in the Constitution, now was wary of national authority. He actually helped the Kentucky legislature to reject federal law. By placing states’ rights above those of the federal government, Kentucky and Virginia had established a precedent that southern states used to justify succession in 1860 at the outset of the Civil War.

John Adams stands as an almost tragic figure.

Since 1765, Adams had been at the forefront of what would become the Revolutionary movement. Although not a striking speaker, his commitment and thorough preparation made him a key figure in the Continental Congress where he served on more committees than any other individual.

Unquestionably an ardent patriot, Adams felt so strongly about the rights of the accused to a fair trial that he represented the British troops who had fired in the Boston Massacre of 1770. Adams argued their case so well that they escaped criminal penalty. During the Revolution, as well as while president, John Adams allowed his principles to determine his course of action even when they made him deeply unpopular.

Adams’ life was marked by many deep contradictions. His conservatism led him to the top of the Federalist Party that by 1800 had become a minority group of elite commercial interests. However, he himself was a man of modest origins who had achieved great success through personal effort. The first in his family to attend college, as well as the first to enter a profession, Adams was caricatured by Democratic-Republicans as an elitist. Meanwhile, the slave-owning gentleman Jefferson successfully campaigned as a defender of the common man.

The new nation that Adams had done as much as any to bring into being was fast becoming a place whose values he did not share. Adams rightly felt misunderstood and persecuted. Writing to another aging patriot leader in 1812, he lamented, “I have constantly lived in an enemy’s Country.”

Toward the end of his long life, Adams renewed an earlier friendship with Jefferson that had understandably dissipated in the 1790s and with the election of 1800. In their waning years, these two towering figures began a rich correspondence that remains a monument of American intellectual expression. Adams’ conservatism exerted itself in a core belief that inequality would always be an aspect of human society and that government needed to reflect that reality.

Furthermore, Adams emphasized the limits of human nature. Unlike the more optimistic Jefferson, Adams stressed that human reason could not overcome all the world’s problems. Less celebrated in both his own day and ours, Adams’ quiet place among the Founding Fathers is related to the acuity and depth of his political analysis that survives in his extraordinarily voluminous writings. Adams persistently challenged and questioned the soft spots of a more romantic and mythical American self-understanding.

In Benjamin Franklin’s estimation, Adams “means well for his country, is always an honest man, often a wise one, but sometimes, and in some things, absolutely out of his senses.”

THE ELECTION OF 1800

The Election of 1800 between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson was an emotional and hard-fought campaign. Each side believed that victory by the other would ruin the nation.

Federalists attacked Jefferson as an un-Christian deist whose sympathy for the French Revolution would bring similar bloodshed and chaos to the United States. On the other side, the Democratic-Republicans denounced the strong centralization of federal power under Adams’s presidency. Republicans’ specifically objected to the expansion of the army and navy, the attack on individual rights in the Alien and Sedition Acts, and new taxes and deficit spending used to support broadened federal action.

Overall, the Federalists wanted strong federal authority to restrain the excesses of popular majorities, while the Democratic-Republicans wanted to reduce national authority so that the people could rule more directly through state governments.

The election’s outcome brought a dramatic victory for Democratic-Republicans who swept both houses of Congress, including a decisive 65 to 39 majority in the House of Representatives. The presidential decision in the electoral college was somewhat closer, but the most intriguing aspect of the presidential vote stemmed from an outdated Constitutional provision whereby the Republican candidates for president and vice president actually ended up tied with one another.

Votes for President and Vice President were not listed on separate ballots. Although Adams ran as Jefferson’s main opponent, running mates Jefferson and Aaron Burr received the same number of electoral votes. The election was decided in the House of Representatives where each state wielded a single vote.

Interestingly, the old Federalist Congress would make the decision, since the newly elected Republicans had not yet taken office. Most Federalists preferred Burr, and, once again, Alexander Hamilton shaped an unpredictable outcome. After numerous blocked ballots, Hamilton helped to secure the presidency for Jefferson, the man he felt was the lesser of two evils. Ten state delegations voted for Jefferson, four supported Burr, and two made no choice.

One might be tempted to see the opposing sides in 1800 as a repeat of the Federalist and Anti-Federalist divisions during the ratification debates of 1788-1789. The core groups supporting each side paralleled the earlier division. Merchants and manufacturers were still leading Federalists, while states’ rights advocates filled the Republican ranks just as they had the earlier Anti-Federalists. But a great deal had changed in the intervening decade. The Democratic-Republicans had significantly broadened the old Anti-Federalist coalition. Most importantly, urban workers and artisans who had supported the Constitution during ratification and who had mostly supported Adams in 1796 now looked to Jefferson. In addition, key Federalist leaders during the ratification debate like James Madison had changed his political stance by 1800. The Father of the Constitution, Madison now emerged as the ablest party organizer among the Republicans. At their core, the Democratic-Republicans believed that government needed to be broadly accountable to the people. Their coalition and ideals would dominate American politics well into the nineteenth century.

As the first peaceful transition of political power between opposing parties in American history, however, the election of 1800 had far-reaching significance. Jefferson appreciated the momentous change and his inaugural address called for reconciliation by declaring that, “We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.”

The harsh public antagonism of the 1790s largely came to an end with the victory of the Democratic-Republicans in the 1800 election. “The Revolution of 1800,” as Jefferson called it, was “as real a revolution in the principles of our government as that of 1776 was in its form.”

To Jefferson and his supporters, the defeat of the Federalists ended their attempt to lead America on a more conservative and less democratic course. Since the Federalists never again played a national political role after the defeat in 1800, it seems that most American voters of the era shared Jefferson’s view. Secondary Source: Drawing

Secondary Source: Drawing

One artist’s idea of what the famous duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr might have looked like.

Jefferson’s election inaugurated a Virginia Dynasty that held the presidency from 1801 to 1825. After Jefferson’s two terms as president, he was followed by two other two-term Democratic-Republicans from Virginia, James Madison and James Monroe. Regular Democratic-Republican majorities in Congress supported their long rule. Political leaders and parties played a pivotal role shaping the new nation because they could serve as outlets for large numbers of people to express their opinions about issues of public significance. For Jefferson, the Election of 1800 stands as a second revolution that protected and extended the gains achieved in the Revolution of 1776.

In one of the more unusual stories of American history, Aaron Burr, who had a long antagonistic relationship with Alexander Hamilton that was exacerbated by Hamilton’s role in the 1800 election, shot and killed him in a duel. Dueling at the time was falling out of favor in the North and evidence suggests that Hamilton purposefully missed on his first shot, assuming that the duel was an exercise in preserving honor. Burr, on the other hand, did not miss. The episode effectively ended Burr’s political career.

JEFFERSON

Jefferson’s lasting significance in American history stems from his remarkably varied talents. He made major contributions as a politician, statesman, diplomat, intellectual, writer, scientist, and philosopher. No other figure among the Founding Fathers shared the depth and breadth of his wide-ranging intelligence.

His presidential vision impressively combined philosophic principles with pragmatic effectiveness as a politician. Jefferson’s most fundamental political belief was an “absolute acquiescence in the decisions of the majority.” Stemming from his deep optimism in human reason, Jefferson believed that the will of the people, expressed through elections, provided the most appropriate guidance for directing the republic’s course.

Jefferson also felt that the central government should be “rigorously frugal and simple.” As president, he reduced the size and scope of the federal government by ending internal taxes, reducing the size of the army and navy, and paying off the government’s debt. Limiting the federal government flowed from his strict interpretation of the Constitution.

Jefferson also committed his presidency to the protection of civil liberties and minority rights. As he explained in his inaugural address in 1801, “though the will of the majority is in all cases to prevail, that will, to be rightful, must be reasonable; that the minority possess their equal rights, which equal laws must protect, and to violate would be oppression.” Jefferson’s experience of Federalist repression in the late 1790s under the Alien and Sedition Acts led him to define more clearly a central concept of American democracy.

Jefferson’s stature as the most profound thinker in the American political tradition stems beyond his specific policies as president. His crucial sense of what mattered most in life grew from a deep appreciation of farming, in his mind the most virtuous and meaningful human activity. As he explained in his Notes on the State of Virginia in 1785, “Those who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God.” Since farmers were an overwhelming majority in the American republic, one can see how his belief in the value of agriculture reinforced his commitment to democracy.

Jefferson’s thinking, however, was not merely celebratory, for he saw two dangerous threats to his ideal agrarian democracy. To him, financial speculation and the development of urban industry both threatened destroy the independence citizens maintained as farmers. Debt, on the one hand, and factory work, on the other, could rob men of the economic autonomy essential for republican citizens.

Jefferson’s vision was not anti-modern, for he had too brilliant a scientific mind to fear technological change. He supported international commerce to benefit farmers and wanted to see new technology widely incorporated into ordinary farms and households to make them more productive.

Jefferson pinpointed a deeply troubling problem. How could republican liberty and democratic equality be reconciled with social changes that threatened to increase inequality? The awful working conditions in early industrial England loomed as a terrifying example. For Jefferson, western expansion provided an escape from the British model. As long as hard working farmers could acquire land at reasonable prices, then America could prosper as a republic of equal and independent citizens.

In spite of the success and importance of Jeffersonian Democracy, dark flaws limited even Jefferson’s grand vision. First, his hopes for the incorporation of technology at the household level failed to grasp how poverty often pushed women and children to the forefront of the new industrial labor.

Second, an equal place for Native Americans could not be accommodated within his plans for an agrarian republic. Third, Jefferson’s celebration of agriculture disturbingly ignored the fact that slaves worked the richest farm land in the United States. Slavery was obviously incompatible with true democratic values. Jefferson’s explanation of slaves within the republic argued that African Americans’ racial inferiority barred them from becoming full and equal citizens.

Jefferson repeatedly acknowledged that slavery was wrong, but he never saw a way to eliminate the institution. To Jefferson, slavery meant holding “a wolf by the ears.” It was a danger that could never be released. Most disturbingly of all, Jefferson could not imagine America as a place where free blacks and whites could live together. To him, a biracial society of equality would “produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of one or the other race.”

Our final assessment of Jeffersonian Democracy rests on a profound contradiction. Jefferson was the single most powerful individual leading the struggle to enhance the rights of ordinary people in the early republic. His Declaration of Independence eloquently expressed America’s statement of purpose “that all men are created equal.” Still, he owned slaves all his life and, unlike Washington, never set them free. For all his greatness, Jefferson did not transcend the pervasive racism of his day.

CONCLUSION

Children often wonder why adults can’t get along. Why do politicians argue? As we get older we can understand how policies that benefit one group of people may be harmful to another. This make sense. Hamilton’s financial plan put the federal government on sound financial footing, but his method benefited his wealthy friends at the expense of the poorer farmers. Jefferson and Madison understood that playing politics could produce electoral victory and harnessed popular discontent to defeat the Federalists.

But did it have to be this way? If Hamilton, Jefferson and Madison had decided that the nation’s leaders need to stay above the level of political feuding, if they had made a point of putting unity over raw political maneuvering, maybe things would have turned out differently.

In the 1780s the nation was not particularly divided regionally. Certainly there was a divide between the East Coast and the Frontier which fueled the Federalist and Democratic-Republican divide, but a strong North and South split had not yet developed. What if the nation’s parties had developed by geographic region? Would the country have survived even a few years?

With all the possible outcomes, it is worth asking, why do we have two major political parties?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The United States has had two major political parties from the very beginning. These developed around the competing ideas of Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson.

As the first Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton proposed important plans to shape the American economy. His ideas reflected his idea that the federal government should be powerful. He wanted the federal government to absorb state debts. This helped northern states who still owed money after the Revolution. It also meant that people would support the federal government because they owned federal bonds.

Hamilton proposed chartering a Bank of the United States to hold federal funds. He believed this large bank would stabilize the economy. Hamilton believed the future of America was based on industry and trade. He wanted to increase tariffs on foreign products to protect American manufacturers. This would hurt Southerners who wanted to purchase imports. Hamilton believed in a loose interpretation of the Constitution. In his view, the Constitution enumerated powers but did not list every possible power of the government. Generally, Hamilton saw Great Britain as an ideal to copy. In his view, the chaos of the French Revolution was a bad example.

The Anti-Federalists changed their name to Democratic-Republicans and were led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison who had grown to distrust Hamilton. They believed the ideal Americans were farmers who were self-sufficient. They saw the French as ideological brothers and distrusted the British. After all, Americans had just finished fighting a war with Britain. Jefferson and Madison were both Southerners and Hamilton’s ideas about tariffs, the bank, and absorbing state debt all benefited northern states at the expense of Southerners. The Democratic-Republicans believed in a strict interpretation of the Constitution. They favored stated powers and feared a power-hungry federal government. In their view, if a power wasn’t listed in the Constitution, the federal government did not have that power.

The new federal government moved to Washington, DC, a brand-new city created in the South. In the beginning, the city was mostly swamp. Adams was the first President to live in the White House.

When John Adams took over as second president, he wanted to continue Washington’s tradition of staying above the growing debate between the two parties, but he failed and both sides turned against him. The XYZ Affair showed growing problems with France. Federalists in Congress passed laws to make criticizing the government a crime, which was a clear political move to silence opponents. In 1800, Democratic-Republicans engineered an electoral victory for Thomas Jefferson.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Alexander Hamilton: First Secretary of the Treasury. He was a Federalist, one of the authors of the Federalist Papers during the debate over ratification of the Constitution. His financial plans included assuming state debts, creating a national bank, and promoting manufacturing. He was killed in a duel with Aaron Burr.

Secretary of the Treasury: The leader of the Department of the Treasury and the person in the executive branch primarily responsible for guiding financial policy.

Pierre Charles L’Enfant: Frenchmen who laid out the street map of Washington, the new national capital.

Federalist Party: One of the first two political parties. They supported the Constitution, strong central government, Hamilton’s financial plans, and favored Britain over France. Washington and Adams were the only president’s from this party.

Democratic-Republican Party: One of the first two political parties. They were the successors to the Anti-Federalists, favored state power fearing tyrannical power concentrated in the federal government. Jefferson and Madison were their leaders.

Aaron Burr: Former Vice President who shot and killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel. Later he moved West and was accused of treason due to his role in a plot to help western states secede from the Union.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Public Securities: Bonds sold by the government. Essentially they are loans people make to the government with a promise of repayment with interest.

Bonds: Essentially an IOU sold by the government. Essentially they are loans people make to the government with a promise of repayment with interest.

Subsidies: Money paid to a certain group of farmers or producers by the government to help support that industry.

Tariffs: Taxes collected on imported goods.

Protectionism: Government policies meant to promote domestic business, either with direct help (subsidies) or by making imports more expensive (tariffs).

Strict Interpretation: A way of reading the Constitution that results in a belief that the government can only do with is expressly written.

Loose Interpretation: A way of reading the Constitution that leads to a belief that the Constitution outlines, but does not express every possible power the government has.

Political Party: A group of people who work together to affect public policy and support candidates for public office.

![]()

GOVERNMENT AGENCIES

First Bank of the United States: Bank created by an act of congress as part of Alexander Hamilton’s financial plan. He hoped that it would help stabilize the nation’s financial system by issuing a stable currency.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Washington, DC: The nation’s capital city, created in the 1790s and designed by Pierre Charles L’Enfant.

District of Columbia: The square area of land selected by President Washington and set aside by Maryland and Virginia for the new national capital. Today the city of Washington has grown to fill the entire area. The part on the Virginia side of the Potomac River was given back to the state of Virginia.

![]()

EVENTS

French Revolution: Uprising in France begun in 1789 by the people against the royalty and aristocrats. It was supported in America by the Democratic-Republicans but eventually dissolved into a reign of terror in which many people were accused and beheaded without a fair trial. It eventually ended with the rise of the dictator Napoleon Bonaparte.

Election of 1800: Presidential election between President John Adams and Jefferson. It resulted in the first transition of power from one party to another.

Burr-Hamilton Duel: 1804 event in which Alexander Hamilton was shot and killed by Aaron Burr.

![]()

LAWS

Alien and Sedition Acts: Laws passed in 1798 by the Federalist congress and President Adams designed to limit the influence of their political opponents. They severely limited the freedom of speech and were clearly in violation of the First Amendment.