INTRODUCTION

Even before the War for Independence ended, his comrades were already calling George Washington the “Father of his Country.” This is an honorific employed in many countries and even in the United States loosely applied to many of the other men who helped Washington create the United States. These Founding Fathers were all important, but perhaps none was more consequential than George Washington. He was one of the wealthiest men in America, successful military commander, and first president. Just about the only thing he didn’t do was to write or sign the Declaration of Independence, which is excusable since he was busy at the time leading the Continental Army.

He walked away from power twice, first when he resigned as commander of the army and went home to Mount Vernon, and then again when he retired after eight years as president. In doing so, he laid a firm foundation for civilian leadership and a regular, peaceful transition of power.

But Washington was human, and subject to all of human flaws. He was an only sometimes successful military tactician, failed to guide the nation away from bitter political divides, and most notably, a slave owner. Meanwhile, many of his contemporaries did brilliant things to help guide the nation toward independence. John Adams doggedly fought the political battles to bring the motion for independence into being. Thomas Jefferson articulated the ideals of the age, Thomas Paine convinced Americans to support the patriot cause, James Madison worked his magic to craft the Constitution, and Alexander Hamilton helped convince the states to support it. Certainly, they are heroes in their own right.

What do you think? Is Washington really the “Father of our Country?”

THE YOUNG GEORGE WASHINGTON

Believe it or not, George Washington was once a kid. He rode horses. He thought about running away from home and going off to sea.

Not only does our assessment of Washington begin before he was famous, but it also starts before the distortions of mythmakers whose accounts of Washington led them to make up stories to explain his greatness. Relatively little information about his early childhood survives, but it’s clear that the story of the cherry tree and that young Washington never telling a lie is itself a fabrication.

He was born in 1732 into a Virginia family of modest wealth. Although not among the richest or most politically powerful families of the day, the Washington household property included 20 slaves by 1743. Had the family fortune continued to expand, Washington might have found himself beginning to enter the top rank of Virginia society. However, inheritance was not to be his route to greatness. George’s father died when he was only 11 and he ended up moving in with Lawrence Washington, his older half-brother.

Lawrence became an important role model for young George. He was particularly impressed by his half-brother’s service in an American regiment of the British Army in a campaign against the Spanish in Colombia, South America.

Another important influence on George was a local boy named George William Fairfax who hailed from a prominent family. Washington’s skill at horseback riding won the favor of the visiting Lord Fairfax. When a surveying party went west to measure the Fairfax’s vast new royal grant of land, 16-year-old George went along for the adventure. More than just fun times, the experience began Washington’s life-long interest in western lands and equipped him with surveying and backwoods skills that would serve him well in the future.

As often happened in the colonial period, early death struck the Washington family once more when Lawrence died in 1752. By the age of 20, George had suffered the death of both his real and surrogate fathers. With his brother’s death, also died George’s hopes to get an education in England, part of the required training for elite men in colonial Virginia.

Instead, George inherited Lawrence’s 2600-acre estate and 18 slaves who made the Mount Vernon plantation profitable. In a colonial world where connections to powerful people and family tradition played an important role in securing public office, George managed to win the title of major in the Virginia militia that had previously belonged to Lawrence. Although lacking significant military experience, George Washington was about to ride into a public career that would carry him to national fame. First, he would have to ride to the frontier and make a name for himself battling French and Native American foes.

THE MILITARY COMMANDER

George Washington carried himself with a grave dignity often described as aloofness. Quite the opposite of being an informal joker, Washington held people at a distance. A central part of his personality included strong self-control that avoided excessive camaraderie. Surely, his long military service played a significant role molding this character. First as a militia officer on the Virginia frontier preceding and during the Seven Years War and then again as the commander of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, Washington believed that familiarity could weaken the respect an officer needed for effective command.

During his first military term, the colonial Governor of Virginia sent Washington west by to try to keep the French out of newly claimed Virginia land on the western side of the Appalachian Mountains. Such an expedition required great skill, not only in order to deal with the French and difficult frontier conditions, but also an awareness of the importance of Native Americans in shaping the balance of power in the contested region. The youthful Washington, in his first significant command, clearly lacked the necessary experience. His rash killing of members of a French diplomatic mission and then his defeat at the Battle of Fort Necessity in July 1754 made for a disastrous start to the Seven Years War. Primary Source: Painting

Primary Source: Painting

George Washington in 1772 as a member of the Virginia militia painted by Charles Willson Peale.

Matters were made worse by the sharp divisions that separated Virginia militia traditions from those of the regular British Army. Where Washington naively thought he had performed rather well and hoped to receive a commission to become a full-fledged British officer, the British saw him as an incompetent provincial officer who lacked the aristocratic birth, the wealth, and the skill required of a proper British officer.

Washington’s experience in the Seven Years War later included some bright moments and he became Virginia’s most celebrated hero of the war, thanks in large part to several remarkable escapes from heavy gunfire. Washington’s leading knowledge of frontier conditions and enormous personal energy had made him a charismatic figure. Overall, his leadership in this first long war was badly flawed.

When Washington returned to active military leadership at the start of the Revolutionary War in 1775, he again faced enormous challenges. However, he also had matured in the decade and a half between conflicts and had developed a much more sophisticated understanding of the political dimension of military leadership. Washington had married the wealthy widow Martha Custis in 1759, and with her money had expanded Mount Vernon and turned it into an impressive plantation. He had served several terms in the Virginia legislature and had become a much more experienced leader.

Washington’s key strategic insight as a wartime leader was to realize that independence depended more on keeping an army in the field than on winning major battles. In spite of a persistent lack of adequate funding from the Congress and in the face of growing conflict from his own officers and enlisted men, Washington held the army together through a skilled combination of discipline and personal example. The army’s survival at Valley Forge in the harsh winter of 1777-1778 is the classic example.

Washington’s greatest contribution to the Revolutionary War, however, was his consistent acknowledgment of the preeminence of civilian leadership. When other military leaders might have been tempted to seize political power and rule as a more efficient strong man, Washington’s respect for the preeminence of civil authority over martial authority kept the republican experiment alive.

In this, he has often been called the “American Cincinnatus,” comparing him to the legendary Roman general who also turned in his sword to once again take up civilian life.

PRESIDENT WASHINGTON

Washington happily resigned his military command at the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783. He saw himself living out his days as a farmer at Mount Vernon. However, he would be called on to lead the country again, this time not in war, but peace.

During the critical period of the 1780s, Washington privately feared that the weak central government dictated by the Articles of Confederation threatened the long-term health of the nation. He supported the call for a Constitutional Convention and after some hesitation attended as a delegate where he was elected the presiding officer.

He took a relatively limited role, however, in the debate that created the proposed Constitution. Nor did he publicly favor ratification. It seems that his sense of personal reserve prevented him from actively campaigning. As he was likely to become the first president, he avoided the appearance of self-serving motivation by not aggressively supporting the Constitution in public.

The significance of the first presidential administration under the Constitution is hard to overstate. The Constitution provided a bare structural outline for the federal government, but how it would actually come together was unclear. The precedent established by the first president would be enormous. Washington generally proceeded with great caution. For the most part, he continued precedents that had been established under the Articles of Confederation. For instance, he carried over the three departments of the government that had existed before the Constitution.

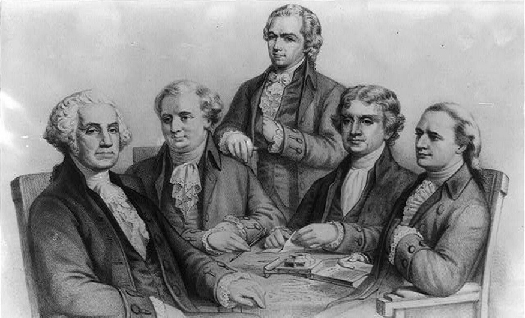

But the nationalist Washington favored a stronger central government and made sure that executive authority was independent from total legislative control. For instance, Washington appointed his own head to each department of government whom the legislature could only accept or reject. Furthermore, Washington identified the three leaders – Thomas Jefferson as secretary of state, Alexander Hamilton of the treasury, and Henry Knox of war – as his personal cabinet of advisers, thus underscoring the executive’s domain. Particularly in his first term as president from 1789-1792, Washington’s enormous personal popularity and stature enhanced the legitimacy of the modest new national government. Secondary Source: Drawing

Secondary Source: Drawing

Washington and his first cabinet. From left to right: President Washington, Secretary of War Henry Knox, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, and Attorney General Edward Randolph.

Unfortunately for Washington, events in his second term somewhat clouded his extraordinary success. For one, his own cabinet split apart as Thomas Jefferson increasingly dissented from the economic policies proposed by Alexander Hamilton, most of which Washington supported.

Even more disturbing to Washington was the emergence of a new form of political activity where the public divided into opposing parties. Although now a fundamental feature of modern democracy, Washington and many others perceived organized opposition to the government as treasonous!

Challenges like the difficulties of his first military command in the 1750s remind us that even this most stellar of the Founding Fathers hardly glided through public life without controversy. As impressive and even as indispensable as Washington had been to the creation of the new nation, he remained a leader with qualities that could not appeal to all of the people all of the time. Most interestingly perhaps is that some of the personal qualities that made him extraordinarily effective are also ones that made him unpopular.

THE WHISKEY REBELLION

One of the most important challenges Washington faced during his presidency, was a rebellion against the power of the new federal government. Much like other rebellions of colonial era, and Shays’ Rebellion, which was very much still a recent event, the Whiskey Rebellion pit Westerners against their government.

New taxes placed on whiskey to increase federal revenue cut deeply into ordinary people’s livelihood. In the newly settled backcountry, poverty was widespread. For farmers to survive economically, they needed to convert bulky corn and grain into more easily transported whiskey. The new taxes debilitated this crucial economic resource for many frontier settlers from New York to Georgia.

In addition, as was the case before, many backcountry settlers simply resented distant rule from the more populous East. For example, anyone in western Pennsylvania facing charges in a federal court had to travel to Philadelphia to stand trial. Moreover, renewed attacks by Native Americans in the early 1790s made Westerners resentful of what they saw as Easterners’ indifference to the risks of life on the frontier. Secondary Source: Painting

Secondary Source: Painting

President Washington directs the federal army during the Whiskey Rebellion. His overwhelming use of force and willingness to lead the army himself while president, are both choices criticized then and now.

The violent climax occurred in the area around Pittsburgh in the summer of 1794. Following a pattern established in the American Revolution, local farmers had begun holding special meetings to discuss their opposition to the tax as early as 1792. A mass meeting in Pittsburgh declared that the people would prevent the tax from being collected and one tax collector was even tarred and feathered in protest.

President Washington declared such meetings unlawful, but among ordinary settlers in western Pennsylvania he was often seen as just another large-scale landowner from the East who didn’t understand local conditions. Many men would not back down in the face of what they considered an oppressive and unjust tax. Matters came to a head when an angry crowd who refused to pay the tax harassed a federal marshal, tax collector, and a handful of federal soldiers. The troops surrendered and the marshal’s house was torched. Other minor protests swept western Pennsylvania and there were rumors of holding a convention to discuss secession from the United States.

Washington reacted dramatically to the violence and the possibility of it spreading to other backcountry areas. Alexander Hamilton had long supported military mobilization to suppress the tax resistance in the west and supported Washington in raising a 13,000-troop force, larger than the Continental Army had ever been. When they arrived in the Pittsburgh area, the resistance dissolved and the federal force had to search hard to arrest twenty men that they accused of involvement in the Whiskey Rebellion.

The rebellion of the summer of 1794 ultimately took on more important symbolic significance than anything else. The federal government had shown itself willing to mobilize militarily to assert its authority. Washington made it clear that the Constitution was the law of the land, and that the federal government would enforce its authority.

But many perceived the sweeping actions of the federal government as going too far. Even an ardent Federalist as Fisher Ames observed that, “Elective rulers can scarcely ever employ the physical force of a democracy without turning the moral force or the power of public opinion against the government.” Like the Shays’ Rebellion eight years earlier, the Whiskey Rebellion tested the boundaries of political dissent. In both instances, the government acted swiftly, and militarily, to assert its authority.

WASHINGTON’ FAREWELL ADDRESS

Washington departed the presidency and the nation’s then capital city of Philadelphia in September 1796 with a characteristic sense of how to take dramatic advantage of the moment.

As always, Washington was extremely sensitive to the importance of public appearance and he used his departure to publicize a major final statement of his political philosophy. Washington’s Farewell Address has long been recognized as a towering statement of American political purpose and until the 1970s was read annually in Congress as part of the national recognition of the first President’s birthday. Although the celebration of that day and the Farewell Address no longer receives such strenuous attention, Washington’s final public performance deserves close attention.

The Farewell Address embodies Washington’s core beliefs that Washington hoped would continue to guide the nation after his presidency concluded. Several hands produced the document itself. The opening paragraphs remain largely unchanged from the version drafted by James Madison in 1792, while Alexander Hamilton penned most of the rest. Although the drawn out language of the Address follows Hamilton’s style, there is little doubt that the core ideas were Washington’s.

The Address opened by offering Washington’s rationale for deciding to leave office and expressed mild regret at not having been able to step down after his first term. Unlike the end of his previous term, now Washington explained, “choice and prudence invite me to quit the political scene, patriotism does not forbid it.” Washington was tired of the demands of public life, which had become particularly severe in his second term, and he looked forward to returning to Mount Vernon.

The fact that he left office after two terms set an important precedent. The Constitution did not specify how long a president could serve. There was nothing preventing Washington from seeking a third term, a fourth, or fifth. However, because he voluntarily stepped down after eight years on the job, all subsequent presidents also followed this tradition, at least until 1940 when Franklin Roosevelt won a third term. After Roosevelt’s fourth election, Americans passed the 22nd Amendment, which limits presidents to two four-year term in office.

Although he might have closed the Address at this point, Washington continued at some length to express what he hoped could serve as guiding principles for the young country. Most of all Washington stressed that the national union formed the bedrock of “collective and individual happiness” for American citizens. As he explained, “The name of American, which belongs to you, in your national capacity, must always exalt the just pride of patriotism, more than any appellation derived from local distinctions.”

Washington accurately foresaw the dangers of regionalism. If Americans identified first with their state, they would not hold together as a single nation. His defense of national unity lay not just in abstract ideals, but also in the pragmatic reality that union brought clear advantages to every region. Union promised “greater strength, greater resource, [and] proportionately greater security from danger” than any state or region could enjoy alone. He emphasized, “your union ought to be considered as a main prop of your liberty.” When American fatally ignored Washington’s advice in the 1850s, Civil War ensued.

The remainder of the Address, delivered at Congress Hall in Philadelphia, examined what Washington saw as the two major threats to the nation, one domestic and the other foreign, which in the mid-1790s increasingly seemed likely to combine. First, Washington warned of “the baneful effects of the spirit of party.” To Washington political parties were a deep threat to the health of the nation for they allowed “a small but artful and enterprising minority” to “put in the place of the delegated will of the Nation, the will of a party.”

Yet, it was the dangerous influence of foreign powers, judging from the amount of the Address that Washington devoted to it, where he predicted the greatest threat to the young United States. As European powers embarked on a long war, each hoping to draw the United States to its side, Washington admonished the country “to steer clear of permanent Alliances.” Foreign nations, he explained, could not be trusted to do anything more than pursue their own interests when entering international treaties. Rather than expect “real favors from Nation to Nation,” Washington called for extending foreign “commercial relations” that could be mutually beneficial, while maintaining “as little political connection as possible.” Washington’s commitment to neutrality was, in effect, an anti-French position since it overrode a 1778 treaty promising mutual support between France and the United States.

Washington’s philosophy leadership, sense that duty and interest must be combined in all human concerns whether on an individual level or in the collective action of the nation permeated the Farewell Address. This pragmatic sensibility shaped his character as well as his public decision-making. Washington understood that idealistic commitment to duty was not enough to sustain most men on a virtuous course. Instead, duty needed to be matched with a realistic assessment of self-interest in determining the best course for public action. Secondary Source: Painting

Secondary Source: Painting

A painting of Washington on his Mount Vernon Plantation completed in the 1800s by Julius Brutus Sterns. His membership in the Virginia planter society is one of the stains on his legacy, at least from a modern perspective.

WASHINGTON AND THE QUESTION OF SLAVERY

George Washington, like most powerful Virginians of the 18th century, derived most of his wealth and status from the labor of African and African American slaves. At his father’s death in 1743, eleven-year-old George inherited ten slaves. His property grew larger with the death of his half-brother Lawrence in 1754, which brought him the 2600-acre plantation of Mount Vernon along with another 18 slaves.

Greater still, was the wealth that Martha Custis brought to the marriage. While most of her slaves remained on other properties, she brought 12 personal slaves with her when she moved to Mount Vernon in 1759. Washington was energetic and purposeful in all aspects of life, which included being a successful plantation master. By 1786 his careful management had increased his property to 7300 acres and 216 slaves.

Washington’s ability as a planter placed him within the traditional gentry elite of Virginia. His wealth rested on the exploitation of humans as property, but he expressed no qualms about benefiting from what we now see as a fundamentally immoral institution. However, the American Revolution challenged Washington’s traditional acceptance of slavery on both pragmatic and idealistic grounds. When Washington arrived in Massachusetts in 1775 to take command of the patriot militia that was surrounding the British in Boston, he was surprised to discover that New Englanders had begun to allow free African Americans as well as slaves to join their ranks as soldiers.

After meeting with his officers, Washington reversed this policy and tried to make an all-white Continental Army. The following month the British Army in Virginia declared that any slave of a patriot master who fled to fight the patriots would gain his freedom.

Washington immediately grasped the strategic crisis posed by this British promise of freedom in a country where one in every five people was black. In fact, seventeen Mount Vernon slaves fled to join the British during the war. Pragmatic concerns quickly led Washington to reverse his policy and by December 1775 the Continental Army, in the North at least, included black soldiers.

Washington’s Revolutionary ideals also helped transform his attitude toward slavery. When contemplating the British actions that compelled him to join the patriot cause, Washington explained to his old friend George Fairfax that British “custom and use shall make us as tame and abject slaves as the blacks we rule over with such arbitrary sway.”

Like many other patriots of the period, Washington described British tyranny as threatening to enslave white Americans. Slavery was the condition that everyone knew to be the most extreme example of human oppression. While the invocation of the slavery metaphor was widespread, Washington went a major step further than most of his fellow slave masters. He decided to limit the severity of his plantation discipline and, ultimately, he even freed his slaves.

Washington’s emancipation of his slaves was an unusual and honorable decision for a man of his day. No other Virginia Founding Father matched his bold steps. By the early 1770s, Washington clearly tried to lessen the evils of slavery on his plantation. From this point on, he rarely bought a slave and never sold them away from Mount Vernon without their consent. Washington hoped to act as a humane master by keeping slave families together. However, he soon discovered that slavery was only profitable when operated in a brutal fashion. Mount Vernon became increasingly inefficient in Washington’s final two decades.

Five months before his death, Washington drew up a will that included a detailed and exact description of how his slaves were to be freed. Beyond freedom, those slaves who were children were to receive occupational training and to learn to read and write, while elderly slaves were to receive financial support. Knowing full well that some heirs would dislike this loss of their potential inheritance, Washington insisted that “this clause respecting Slaves, and every part thereof be religiously fulfilled … without evasion, neglect, or delay.”

In spite of these far reaching and unusual actions, Washington was still a man of his time. At his death in 1799, Mount Vernon included 317 slaves, but only 124 of them belonged to George and only these would be freed. The rest were Martha’s. Temporarily inherited from her deceased first husband, they would pass to her heirs upon her death and could not be legally controlled by George. More significantly, however, Washington never publicly explained his new belief that slavery should end.

In a private letter in 1786 he stated, it is “among my first wishes to see some plan adopted, by the legislature by which slavery in this Country may be abolished by slow, sure, and imperceptible degrees.” Even his private commitment was to a cautious and gradual process, but he never allowed even this moderate anti-slavery position to be known publicly. In the end, Washington’s commitment to national unity prevented him from throwing his enormous public stature behind the radical cause of emancipation. He feared that such action would deeply divide the new nation.

Could Washington have forged an anti-slavery coalition that might have ended the evil institution and avoided the bloodshed of the Civil War? Might public action on his part have caused an earlier civil war that would have wrecked the nation still in its infancy? Those are questions that history cannot answer and that we can never know, but it is clear that in his own cautious way Washington struggled with the most profound question of the Revolutionary Era and ultimately decided, as did all the member of the Founding Generation, that a union with slavery was preferable to disunion without.

CONCLUSION

Like many of the members of the Founding Generation, Washington is a bit of a mixed bag. He was careful about the precedent he was establishing and did his best to set a good example, but as a product of his time, he acted on the assumptions and prejudices that we find abhorrent today.

Maybe this is what makes us most uncomfortable. In a recent debate about removing statues of Confederate generals, President Trump wondered if we should take down statues of all slave holders. Most historians were quick to argue that there is a difference between the Southerners of the Civil War and the Southerners of the Revolution, but Trump has an interesting point, albeit expressed in a rather crude manner.

Can good acts outweigh participation in the slave system of the pre-Civil War Era? Should we mythologize some slave owners and demonize others? What makes Washington different? Why should he be the “Father of the Nation” while others are relegated to secondary or pariah status?

What do you think? Does he deserve his title?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: It is difficult to understate the importance of George Washington on the founding of the United States. He led the army in the War for Independence and served as the nation’s first president.

George Washington had been a surveyor in Virginia. He was not poor, but not rich until he married into a wealthy family. He played an important part in the start of the Seven Years War, which gave him credibility with Congress who appointed him leader of the Continental Army during the Revolution.

Washington was not a brilliant military commander but was charismatic and inspired confidence and loyalty. Importantly, he respected the idea of civilian leadership and refused to become king, although he certainly could have used his army, and popularity to take power for himself.

Washington generally supported the Federalist idea of strong central government, although he did not like political parties and discouraged them during his eight years in the presidency.

Washington understood the importance of precedent and made careful choices as the first president. He created the cabinet of advisors, a tradition still in place today.

When farmers in the mountains of Virginia rebelled against a tax on whiskey, Washington led an army to put down the rebellion, thus reinforcing the new federal government’s power.

At the end of two terms Washington refused to be elected again. This created an important tradition that was respected for almost 200 years. When leaving office, he gave a farewell address that encouraged his countrymen to avoid forming political parties or engaging in alliances with foreign nations.

A persistent criticism of Washington is that he was a slave owner. However, Washington had mixed feelings about slavery. At the end of his life, he believed slavery should end and in his will he emancipated his slaves.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Cabinet: The leaders of the various executive branch departments and agencies that advise the President. This group is not established by the Constitution, but was a precedent established by President Washington.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Precedent: An established tradition based on the first time an event occurred. Washington was cognoscente that his actions would establish these.

Emancipation: The act of freeing slaves.

![]()

SPEECHES

Washington’s Farewell Address: Letter and speech by President Washington at the end of his tenure summarizing his political philosophy and outlining his recommendations for the nation. Most remembered, he warned against entering into foreign alliances.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Mount Vernon: George Washington’s plantation in Virginia.

![]()

EVENTS

Whiskey Rebellion: An uprising in 1794 in the backcountry of Virginia against a government tax on whiskey production. President Washington responded by leading the army to enforce the tax, establishing the power of the new federal government to enact and collect taxes.

![]()

LAWS & RESOLUTIONS

22nd Amendment: Constitutional amendment ratified in 1951 limiting the president to two four-year terms. It legalized the precedent established by President Washington and broken only by Franklin Roosevelt.

Did Washington set any other precedents?

What would have happened if Washington had stepped down after his first term?

Good for Washington coming out of retirement for America but I could never once I retire you will never see me take on any high-stress activity and I’ll happily be doing nothing all day.

Why cannot George Washington write his own speech?

What if Washington didn’t have any remorse for his slaves and still kept them?

How would the country change if Washington had only served one term? Most of the following presidents would have served one term creating a larger variety of leaders.

How does the Whiskey Rebellion relate to protests seen today? Does this pattern often repeat when it comes to modern day protests?

Why did Washington still keep some of his slaves?

I understand why Washington was not publicly and explicitly open about his views on slavery because as the first president, it would making people strongly for or strongly against him.

In what ways did Washington’s horseback riding and surveying/ backwood skills translate to the battle field?

Even though Washington only stayed for 2 terms there was nothing in the Constitution at the time that wouldn’t allow other Presidents to do more than that, so what made the other Presidents follow that same rule? Was it the respect they had for Washington?

How did Martha feel about Washington setting all of his slaves free?

If such a prominent figure such as Washington were to voice against slavery publicly, would everyone follow or would have the Civil War began sooner?

How did Washington get the title major in the Virginia militia with Zero military experience?

How did American farmers know to create whiskey from grains and corn? Was this tradition brought by the Scottish- Irish?

Why was there such a big difference between what some people thought of slaves and their actions? I would assume that Washington was not the only one to think that slavery was wrong. Why couldn’t they just take the risk to help free the slaves?

How did George washington treat his slaves?

did he ever regret having slaves?

If George Washington had publicly spoken about how cruel and evil slavery was back then, would anything have changed today?

Why did Washington not want his anti-slavery stand to be private? Did he want it to be private so that other slave owners don’t judge him and criticize him?

Was it necessary for Washington to keep slaves? Could he have done the work on his plantation by himself or did he really need the slaves? Why?

I imagine since all the wealthy large-land owners had used the act of slavery to benefit themselves, it seemed only right for Washington to follow this method too. George Washington was the first ever president of the United States of America. This enormous role alone would direct his entire focus on uniting the nation, paying little attention to and leaving little time for him to be at Mount Vernon. Although it was wrong, using slaves allowed him to maintain his business while focusing on other issues.

I agree with Katie, He had a big role being a president to the United States and other things. I also don’t think its humanly to possible to do work that is done by 100s of people in a 7300 acre land alone.

how did george washington get elected? and considered as the first president?

I think he was elected by Electoral College. I know he did many things for the United States, but I’m also curious on why he was considered as the first president since many people did many things for the United States too. What made him so special that his actions establish things (precedent)?

What caused Washington to stay for another term? Did he really want to be president?

He feared that such action on anti-slavery would deeply divide the new nation. In what ways would it divide the nation?

I think he feared diving the nation into two parts, pro-slaves and anti-slaves. Especially when the states finally came together to make one central government, such division was not beneficial.

Why did Washington prevent his anti-slavery stance from becoming public? Was it for the purpose of his reputation? If he spoke out about his stance would more people have agreed to the act of slavery being wrong? If he announced his new stance on slavery, would there have been an effect on when the abolishment of slavery would have been later on?

Although Washington disliked British’s ways, he understood what their intentions were, he was able to make a change to not do and do what the British’s did. He understood British’s promised ⅕ slaves freedom, and changed his attitude. Like in his will he wanted to emancipate all his slaves.

Why didn’t Washington want to get involved in foreign relations and why did Washington think that this was a treat to the nation? Washington had a huge commitment to neutrality, and what would have happened if during 1778 we as a nation did not sign a treaty promising mutual support between France and the United States.?

Why wasn’t Washington open to supporting the ratification of the Constitution, even though he was a federalist? Did he do this to avoid conflict from Anti-federalists and instead, gain public admiration?

Did Washington keep his views on slavery private in order to avoid conflict in the nation or was it because he feared that others would disagree and not follow him?

I believe that both are correct about Washington’s reasons as to why he never announced his perspective about slavery. In the reading, it mentioned that George Washington had feared that publicly releasing his views about emancipation would “deeply divide the new nation.” In other words, this meant that Washington was considering the possibility of more rebellions, violence, or some states seceding from the US if he ever publicly announced his opinion. Examples of Washington’s fears could be the actions of the Southern States, especially since their economy rode on slave labor. I still feel that Washington should’ve attempted to announce his opinion because it could’ve prevented the deaths of many people during the Civil War. However, it could’ve started an early civil war, that would’ve left our new country in shambles. Although big actions to stop slavery did not occur until later on, I’m still very appreciative that Washington came to his senses about how immoral slavery was, and how he took a small step to emancipate and support the slaves on his own end.

Why did Washington’s viewpoint of slavery take such a drastic turn after he saw the British giving incentives for slaves to join their army? (I know that the British was getting stronger because of the higher numbers, but why did that make him in the end emancipate slaves and turn his previous viewpoint around 180)

Maybe he was afraid all the slaves would leave to get an incentive for siding with the British.