INTRODUCTION

A quick glance at the tags on your clothes or the labels on products at our favorite stores will reveal that very few of the things we buy are actually produced in the United States. Instead, countries such as China, Taiwan, Japan, Vietnam, India and Bangladesh appear frequently. Why is this? What happened to the gigantic factories of the Midwest and Northeast that fueled the industrial revolution of the late 1800s? What happened to the workers who made the United States the Arsenal of Democracy during World War II?

Some might say that this is good for our country. We have more options. We can compare American cars with Japanese, Korean, and European imports and buy the one that is best. But, when did these foreign automakers start selling their cars in the United States to begin with? And, why didn’t the Detroit automakers do something to protect their market share? What about our presidents and congress? Why didn’t they do something to protect American business and workers?

Then, there is the question of America’s wealth. What’s happening to the money we spend when we go to the store? Is it leaving the country to pay foreign workers?

What do you think? Is it bad for America that so few of the things we buy are made here?

THE NIXON SHOCK

In 1944 in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, representatives from 44 nations met to develop a new international monetary system that came to be known as the Bretton Woods system. Conference members hoped to find a way to ensure global financial stability and promote economic growth. In the Bretton Woods system, countries agreed to settle their international accounts in American dollars. For example, France used American dollars to pay its debts to West Germany rather than using French Francs or German Marks. The dollar was fixed at $35 per ounce in gold, which was guaranteed by the United States Government. This system is called the gold standard. Thus, the United States was committed to backing every dollar with gold, and other currencies were pegged to the dollar.

For the first years after World War II, the Bretton Woods system worked well. Western capitalist systems thrived. With the Marshall Plan, Japan and Europe rebuilt from the war, and countries outside the United States wanted dollars to spend on American goods. Because the United States owned over half the world’s official gold reserves, the system appeared secure. Secondary Source: Chart

Secondary Source: Chart

This chart shows the number of banking crisis each year beginning in 1800. While the Bretton Woods System was in place, there were almost no incidents.

However, from 1950 to 1969, as Germany and Japan recovered and increased production, America’s proportion of the world’s economic output dropped significantly, from 35% to 27%. Furthermore, America began spending more on foreign goods than it sold. Money started flowing out of the United States. At the same time, public debt was growing as a result of spending on the Vietnam War, and monetary inflation by the Federal Reserve caused the dollar to become increasingly overvalued.

By the end of the 1960s, other nations were beginning to dislike the Bretton Woods system. As American economist Barry Eichengreen summarized, “It costs only a few cents for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to produce a $100 bill, but other countries had to pony up $100 of actual goods in order to obtain one.”

By 1966, the United States did not have enough gold on hand to back up all the dollars held by foreign governments. In May 1971, West Germany was fed up with the limitations of staying in the Bretton Woods system. Unwilling to revalue the Deutsche Mark, the West German government decided instead to abandon the system altogether. In the following three months, this move strengthened the West German economy. Simultaneously, the dollar dropped 7.5% against the Deutsche Mark. Other nations began to demand redemption of their dollars for gold. Switzerland redeemed $50 million. France acquired $191 million in gold. Under the Bretton Woods system, the American dollar was always valued at $35 per ounce of gold. As the European nations abandoned the system, the dollar fell in value.

To combat these problems, President Nixon decided to break up Bretton Woods by suspending the convertibility of the dollar into gold. This prevented a run on the American gold by foreign governments. To prevent panic in the markets, he also instituted a 90-day freeze on wages and prices.

The Nixon Shock, as his decision is now known, has been widely considered a political success, but had mixed results for the global economy. The dollar plunged in value by a third during the 1970s. In 1996, Nobel Prize winning economist Paul Krugman summarized the post-Nixon Shock era as follows: “The current world monetary system assigns no special role to gold; indeed, the Federal Reserve is not obliged to tie the dollar to anything. It can print as much or as little money as it deems appropriate. There are powerful advantages to such an unconstrained system. Above all, the Fed is free to respond to actual or threatened recessions by pumping in money. To take only one example, that flexibility is the reason the stock market crash of 1987 – which started out every bit as frightening as that of 1929 – did not cause a slump in the real economy. While a freely floating national money has advantages, however, it also has risks. For one thing, it can create uncertainties for international traders and investors. Over the past five years, the dollar has been worth as much as 120 yen and as little as 80… Furthermore, a system that leaves monetary managers free to do good also leaves them free to be irresponsible…”

The most immediate result of the Nixon Shock, was economic stagflation.

STAGFLATION

Americans were accustomed to steady economic growth since the end of World War II. Recessions had been short and were followed by robust economic growth. But in the 1970s, for the first time since the Great Depression, Americans faced an economy that could result in a lower standard of living for their children. The problem was a dangerous combination of three factors.

Inflation is the slow increase of prices over time. Some inflation is usually good for an economy, but inflation, which had crept along at 1% to 3% for the previous two decades, exploded into double digits. At the same time, the unemployment rate was nearing the dangerous 10% line. Not since the Great Depression of the 1930s had so many Americans been looking for work. Economic output also stalled. Americans were simply not able to produce and sell as much as they were accustomed to. This situation is stagflation, a disastrous blend of high inflation, high unemployment, and low economic growth.

Americans’ confidence faltered. They began to ask themselves what had gone wrong.

Richard Nixon tried to fight inflation first by cutting government spending, but ultimately by imposing wage and price controls on the entire nation. President Ford watched the inflation rate soar above 11% in 1974. He enacted a huge propaganda campaign called Whip Inflation Now (WIN), which asked Americans to voluntarily control spending, wage demands, and price increases. The struggling economy, along with his pardon of Nixon after the Watergate Scandal, led Americans to sour on President Ford and they handed the presidency to Jimmy Carter in the 1976 election.

Carter was viewed by many as a breath of fresh air. He was deeply religious, a peanut farmer, and the governor of Georgia. Unlike Nixon, Carter had the reputation of being an honest tell-it-like-it-is person. Carter tried tax and spending cuts, but the annual inflation rate topped 18% under his watch in the summer of 1980. At the same time, the unemployment rate fluctuated between 6% and 8%.

OIL, CARS, AND CRISIS

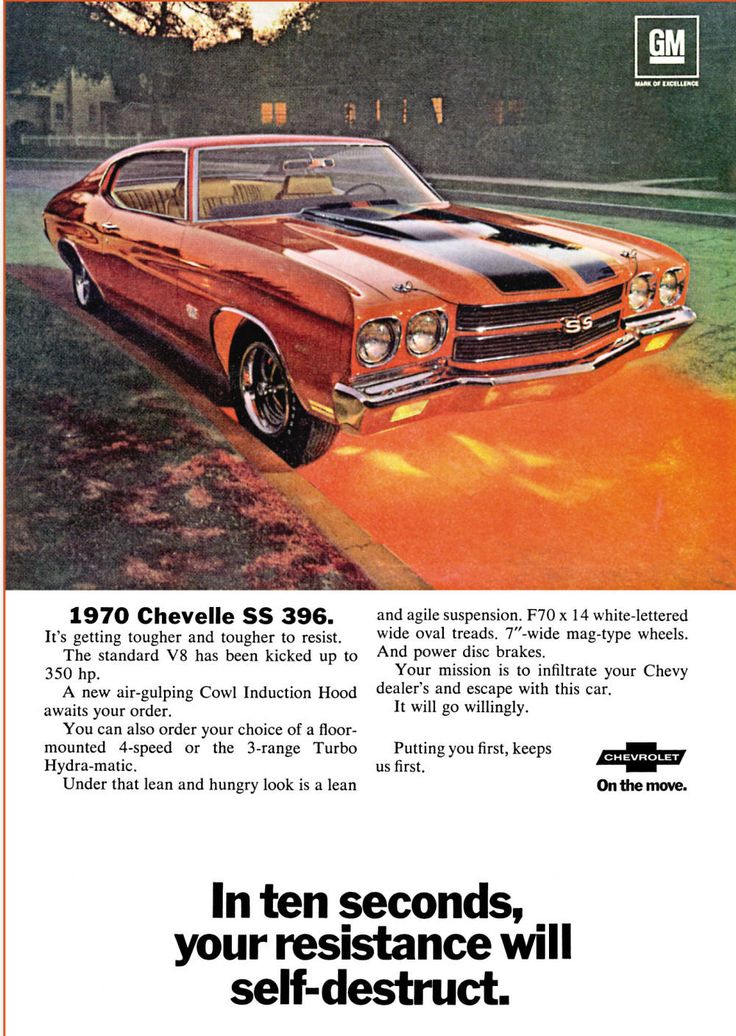

Before the 1970s, the most popular cars in America were large, heavy, and powerful. In 1971, the standard motor for the popular Chevrolet Caprice was a 400-cubic inch (6.5 liter) V8, which achieved no more than 15 highway miles per gallon. Detroit’s Big Three – General Motors, Chrysler and Ford – had dominated the automobile market for decades. Without competition, they had grown complacent, making ever larger, heavier and less efficient vehicles. To make matters worse, in the 1970s, Americans fell in love with big, powerful muscle cars that boasted the least fuel-efficient engines of all. They might have been fun to drive, but they were time bombs for America’s economy. Primary Source: Advertisement

Primary Source: Advertisement

The 1970s Chevelle SS 396, a classic example of the large, fuel-hungry, muscle cars popular in the late 1960s and early 1970s. They were fun to drive but terrible to own when gas prices soared.

When Israel defeated its Arab neighbors in the Yom Kippur War of 1973, Arab oil producers retaliated against Israel’s allies by leading the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to enact an embargo. They agreed to significantly limit the quantity of oil they exported to the United States. The prices of oil-based products skyrocketed in the United States as demand outstripped supply. Automobiles and drivers sat in long lines at service stations, and everyone felt the pain of paying more at the pump as the price of gasoline quadrupled.

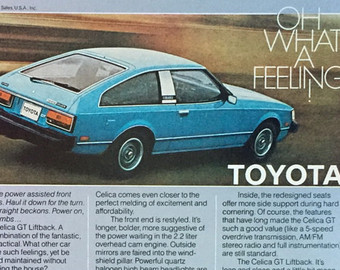

With skyrocketing prices, the much smaller, far more efficient Japanese and European cars that utilized four-cylinder engines, unibody construction, and front-wheel drive dramatically increased in popularity. American automakers’ attempts at compensating were relatively poorly received as they offered vehicles that were still less efficient and less well constructed than the imports. The Detroit automakers simple could not adapt fast enough. Some of the failed American cars of the 1970s such as the Chevrolet Nova and Ford Pinto are remembered as cautionary examples of hubris. It took General Motors, Christer and Ford a decade to recover. In the meantime, Japanese and European cars became common on American roads. Primary Source: Advertisement

Primary Source: Advertisement

A magazine ad for a Toyota. These smaller, more fuel-efficient imports became popular during the fuel shortages of the 1970s and were a major blow to the Big Three American carmakers.

The government’s response to the embargo was quick but had limited effectiveness. A national speed limit of 55 mph was imposed to help reduce consumption. President Nixon named William E. Simon as Energy Czar, and in 1977, a cabinet-level Department of Energy was created. The government established the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. Today the reserve holds roughly 700 million barrels of oil in tanks in Louisiana and Texas, enough to provide the United States with all the oil it needs for about a month.

But with demand high and supply low, gas stations were hurting. The American Automobile Association reported that in the last week of February 1974, 20% of American gasoline stations had no fuel to sell. Tens of thousands of local gasoline stations closed during the fuel crisis.

In an effort to reduce consumption and alleviate the pressure on gas stations, some state governments instituted rationing. Odd–even rationing allowed vehicles with license plates having an odd number as the last digit to buy gas only on odd-numbered days of the month, while others could buy only on even-numbered days. Americans loved their cars. American cities had been built with cars in mind. Americans drove from the suburbs to shopping malls and into downtowns to work. They took long vacations in their cars. Cars were to the modern American what horses had been to the cowboys. Americans hated rationing. Limits on gasoline even led to violent incidents when truck drivers chose to strike for two days in December 1973. In Pennsylvania and Ohio, non-striking truckers were shot at by striking truckers, and in Arkansas, trucks of non-strikers were attacked with bombs. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Lines of cars waiting to purchase gasoline during the oil crisis. Notice the rationing sign indicating even numbered cars only on that day.

THE GREAT MALAISE

In 1979, President Carter left for the presidential retreat of Camp David, conferring with dozens of prominent political leaders and other individuals to try to find a solution to the nation’s trouble. His pollster, Pat Caddell, told him that the American people simply faced a crisis of confidence stemming from the assassination of major leaders in the 1960s, the Vietnam War, and the Watergate scandal.

When he came back to the White House on July 15, 1979, Carter gave a nationally televised address in which he told the American people, “I want to talk to you right now about a fundamental threat to American democracy… I do not refer to the outward strength of America, a nation that is at peace tonight everywhere in the world, with unmatched economic power and military might. The threat is nearly invisible in ordinary ways. It is a crisis of confidence. It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will. We can see this crisis in the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives and in the loss of a unity of purpose for our nation…”

This came to be known as his Malaise Speech, although Carter never used the word in the speech. Carter juxtaposed crisis and confidence to explain how overconsumption in the United States was leading to an energy crisis. Although at first this resonated with the public and he went up in opinion polls, there was a boomerang effect and the speech prompted a public backlash. Some thought that Carter was blaming the American people for having lost a can-do spirit. Carter’s critics argued that it was the president himself who was suffering from a malaise. If he were actually a strong leader, they said, he would fix the energy crisis himself.

Three days after the speech, Carter asked for the resignations of all of his cabinet officers, and ultimately accepted those of five who had clashed with the White House the most. The Malaise Speech and the subsequent cabinet shake-up were poorly received by the public and media who viewed it as evidence that Carter didn’t have a clear plan to fix the nation’s ailing economy.

In the presidential election of 1980, former Hollywood actor and California governor Ronald Reagan easily defeated Carter. Americans were drawn to his confident, optimistic message. One of his campaign ads asserted that it was “Morning Again in America.” After years of scandal and economic hardship, Americans were indeed ready for a new start.

GLOBALIZATION

Trade between cities and nations has been a reality since ancient times. The United States was involved in international trade even before it was a nation. Spanish conquistadors exported gold and silver. French trappers sent beaver pelts home to Europe and the colonists in New England and Virginia shipped tobacco, fish and lumber to England. But for the most part, producers and consumers in the United States dealt mostly with products that were not from other countries. They ate food grown in nearby farms. Americans drove cars built in Detroit. They flew in planes built in Seattle. They toasted their bread, mowed their lawns, washed their clothes and cooked their food with appliances made in America.

All that changed in the last quarter of the 20th Century in a process dubbed globalization. Beginning in the 1970s, American manufacturing companies found it harder and harder to compete with foreign importers. Sometimes it was because of years of poor choices, as was the case of the Detroit automakers who simply were not designing cars that people wanted to buy. In other cases, larger factors such as the Nixon Shock changed the value of American money in the global marketplace and gave foreign companies an advantage. Without the Bretton Woods system maintaining the value of the dollar for example, Japanese electronics companies could sell televisions in the United States and make more money than before. Sony, Panasonic, Sharp, Pioneer, Casio, and Yamaha became familiar names on American store shelves. Secondary Source: Chart

Secondary Source: Chart

This chart shows the balance to trade for the United States beginning in 1895. Until 1970, America sold more products to the world than it purchased. After 1975, Americans have always imported more than exported. This is called the trade deficit.

As the years wore on, more and more products that had once been built in the United States were being made elsewhere. In the case of the auto industry, foreigners simply replaced American companies. In others, American companies outsourced their production to where the cost of labor was significantly less. This was especially true in the textile industry. During the 1970s and 1980s, 95% percent of the looms in North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia shut down. The effect was devastating for the local economies. In some towns everyone either worked in a textile mill, was related to someone who did, or worked in a business that supported these workers.

From coast to coast, the working class people of America faced growing competition from workers in distant countries and more often than not, the American workers were losing. Nowhere was this more evident than in the industrial heartland of the Midwest.

THE RUST BELT

In the 1800s, the cities of the Midwest boomed and immigrant workers flooded in to find work in the Industrial Revolution’s new factories. Carnegie’s steel mills and Henry Ford’s auto plants, Rockefeller’s oil refineries and Pullman’s railroad car company stood out as examples of the ingenuity that were hallmarks of the age. The industrial heartland of the United States reached its zenith during World War II when its factories transformed themselves into the Arsenal of Democracy.

With the decline of manufacturing jobs in the 1970s and 1980s, the great industrial cities of the Midwest were dealt a massive blow. Factories closed. Workers were laid off. People moved away to look for work. Business owners faced loss revenue as their customers had less to spend. City governments struggled to maintain services as tax revenue fell. Schools closed. In some places, whole neighborhoods were abandoned. Crime and drug abuse increased. Middle class families who could, moved into more prosperous suburbs leaving inner cities empty. In many cities only the poor African American families remained. Demographic maps of cities like Detroit or Cleveland show rings of mostly White suburbs around nearly 100% African American urban cores. Laws, government policies, and racist business practices ensured that neighborhoods remained segregated. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

One of the many abandoned houses in Detroit, Michigan. These were once thriving neighborhoods of row houses, but are now abandoned.

A new term was coined to describe the region of abandoned steel mills, railroad yards, automobile factories and manufacturing centers: the Rust Belt. What had once been a source of American pride, the region that had fueled the growth of the nation, became a symbol of its decline. Abandoned factories, boarded up storefronts, and graffiti-covered vacant homes continue to be scars that show how far America’s heartland fell. Secondary Source: Map

Secondary Source: Map

This map shows the rate of manufacturing job loss in the past four decades. The darker red the color, the greater number of manufacturing jobs disappeared.

Problems associated with the Rust Belt persist even today, particularly around the eastern Great Lakes states. From 1970 to 2006, Cleveland, Detroit, Buffalo, and Pittsburgh lost about 45% of their population. Median household incomes fell in Cleveland and Detroit by about 30%, in Buffalo by 20%, and Pittsburgh by 10%.

Not all production in the United States ended, however. In the late-2000s, American manufacturing recovered faster from the Great Recession of 2008 than the other sectors of the economy, and a number of initiatives both public and private, are encouraging the development of new technologies that will provide jobs for unemployed laborers. Despite its decline, the Rust Belt still composes one of the world’s major manufacturing regions. While there are examples all across the Midwest of decay, there are places where prosperity seems to be growing out of the ashes. The great Bethlehem Steel Works in Pennsylvania closed its doors in 1995 after 140 years of production, but the rusting hulk was torn down and the site is now the home to a hotel and casino.

THE FORMAL STRUCTURES OF GLOBALIZATION

In the wake of the Second World War, the major nations of the world sought ways to develop a more integrated, stable and peaceful world. The Bretton Woods system and the United Nations were aspects of this effort. In addition, the World Trade Organization (WTO), International Monitory Fund (IMF) and World Bank were established. The WTO provides a framework and forum for negotiating and formalizing trade agreements. In effect, the WTO exists to help eliminate barriers to trade between countries. The IMF was created to be a super-bank for the governments of the developing world to help them access funds when private banks were too weak, thus ensuring stability in global markets. The World Bank uses money loaned from wealthy nations to finance development projects such as constructions of airports, irrigation systems, or programs to fight hunger and disease in the Third World.

Like most nations, the United States has concluded many free trade treaties. Most famous of these is the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Concluded in 1994, the agreement between the United States, Canada and Mexico eliminates tariffs on products transferred between the three nations. For example, Canada will not charge a tariff, or tax, on pork products brought across the border from American farms and sold to Canadian consumers. Globally, the most famous of all such free trade zones is the European Union’s open market, which encompasses most of mainland Europe and many of the United States’ closest allies.

The leaders of the major industrial nations of the world meet every few years to discuss economic issues. These grand summits of the leaders of the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy and Japan are known as the G7, short for Group of Seven. For a while, it was the G8 while Russia was invited. Interestingly, China is not included although it is the world’s second largest economy.

ANTI-GLOBALIZATION

There are outspoken critics of the process of globalization, and the visible manifestations of globalization such as the IMF, WTO, G7 and NAFTA are their favorite targets. Sometimes called the anti-globalization movement, these activists base their criticisms on a number of related ideas. Some members of the movement oppose large, multinational corporations. Specifically, they accuse corporations of seeking to maximize profit at the expense of workers, pay, and environmental conservation. They point to examples of Third World workers being paid wages far less than American workers and being forced to work long hours in dangerous factories as evidence of unregulated corporate evil.

Other participants in the movement fear that globalization is leading to a decrease in democratic representation as more and more of the decisions that affect daily life are made by corporate executives and the leaders of multi-national organizations such as the World Trade Organization. Unlike a mayor who might be voted out of office for failing to maintain city roads, the leaders of global organizations seem far away from the ability of individual voters to control. For some, this is a threat to national sovereignty itself. What makes someone American if globalization has made markets and public policy a matter of international concern? These anti-globalists believe modern companies are manipulating even the United States government, just like American Dollar Diplomacy made use of corporate power to manipulate governments in Latin America. In 2010, the Supreme Court ruled in Citizens United v. FCC that corporations and organizations have an equal right to free speech under the First Amendment. This decision erased limits on political spending by companies. Without limits, the executives of a company like Exxon-Mobile can spend billions of dollars on political ads to influence an election. Although companies cannot vote, their leaders can use corporate money to control political debate in ways that everyday citizens cannot. Some of the people who worried about this loss of political control were motivated in 2016 to vote for Donald Trump with his promises of “America First” and “Drain the Swamp.” The Occupy Wall Street movement that started in New York City in 2011 is an example of people organizing against perceived influence of powerful banks.

Another criticism of globalization is the destruction of local culture. If Italians start drinking Starbucks instead of stopping at local cafes, local identity suffers. If people in the mountains of Bolivia give up indigenous styles of dress in favor of American jeans and t-shirts, local culture begins to fade. When Mongolian teenagers watch Hollywood movies and listen to American pop music, they are diluting their own culture with the global culture of the American entertainment industry. In these and many other cases, anti-globalists point to the loss of diversity and identity as downsides of globalization. Because of the title of Benjamin Barber’s famous book describing this process, it is often called “McWorld.”

Many anti-globalization activists do not oppose globalization in general. Rather, they call for forms of global integration that better provides for democratic representation, advancement of human rights, fair trade and sustainable development. For example, these people believe free trade agreements should include protections for the workers and the environment. Rather than anti-globalist, this group is now known as the Social Justice Movement. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

An activist at the Occupy Wall Street movement in New York City in 2011. The 99% rallying cry makes that case that only 1% of the world’s people control most of the world’s wealth. The protestors believed that this situation damages the democratic principle of one person, one vote.

It appears the process of globalization is irreversible. We seem to be more and more integrated with each passing year. The question that remains for both proponents and opponents of globalization is: what will the costs and benefits be, and for whom?

FIGHTING GLOBALIZATION

Some activists have taken to the streets to protest the injustices they feel are being done in the process of globalization. Most notably in the United States, when the World Trade Organization member nations met in Seattle, in November 1999, protesters blocked delegates from entering meetings and forced the cancellation of the opening ceremonies. Protesters and Seattle riot police clashed in the streets after police fired tear gas at demonstrators. In what protesters called the Battle in Seattle, over 600 people were arrested and thousands were injured. Three police officers were injured by friendly fire, and one by a thrown rock. Some protesters destroyed the windows of storefronts of businesses owned or franchised by targeted corporations such as a large Nike shop and many Starbucks locations. The mayor put the city under the municipal equivalent of martial law and declared a curfew. The Seattle protests shocked American leaders who underestimated public discontent and Americans in general were surprised to see images of peaceful protesters being attacked with tear gas in the streets. For many, it reminded them of the chaos of the 1960s. By 2002, the city of Seattle had paid over $200,000 in settlements of lawsuits filed against the Seattle Police Department for assault and wrongful arrest, with a class action lawsuit still pending. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Seattle police officers in riot gear spray protesters with tear gas during the Battle in Seattle. Police tactics in Seattle and Washington, DC were seen as evidence that governments were siding with corporations against the will of the people.

After the Seattle WTO protests, Canadian author Naomi Klein published a book entitled “No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies” which became the unofficial manifesto of the anti-globalist movement. In her book, Klein argued that corporations have used their economic influence to hurt workers, muzzle dissent, and enrich their shareholders at the expense of average citizens in both wealthy and developing nations.

Encouraged by the disruption they caused and media attention their actions received, protesters repeated their efforts in Washington, DC in 2000 when roughly 15,000 people demonstrated at the annual meeting of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. Police raided the activists’ meeting hall. DC police arrested more than 1,300 people and after lawsuits, $13.7 million in damages were awarded to the protesters who had been arrested and injured. In 2002, some 1,500 or more people gathered again to demonstrate against the annual meetings of IMF and World Bank in the streets of Washington DC. Again, hundreds of people were arrested, and just like before, the city had to pay the protesters to end a lawsuit.

Similar protests have erupted in cities around the world when economic summits were held in Genoa, Berlin, Paris, and Madrid, among others.

Despite the public attention these clashes have produced, they seem to have had little effect on the process of globalization itself. One argument often made by their critics is that a major cause of poverty among Third World farmers is the trade barriers put up by rich nations and poor nations alike. The WTO was created specifically to work towards removing those trade barriers. Therefore, they argue, people really concerned about the plight of the Third World should be encouraging free trade, rather than attempting to fight it. Indeed, people from developing countries have been relatively accepting and supportive of globalization while the strongest opposition to globalization has come from wealthy First World activists and labor unions.

In the past few years, however, anti-globalization activists have found a receptive ear among some politicians in Europe and the United States, especially regarding free trade agreements. In the United States, President Trump won popularity in his 2016 campaign by attacking NAFTA and as president renegotiated the agreement. In 2020, he signed the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) which is an update to NAFTA. As a candidate Trump also criticized another free trade agreement called the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) that was to include 12 nations on either side of the Pacific Ocean. Although former president Obama had committed the United States to joining the TPP, as president, Trump withdrew from the pact. Around the same time that Trump was capitalizing on fears of free trade in the United States, a movement developed in the United Kingdom to leave the European Union. A referendum held in 2016 led to a narrow victory for those seeking to leave and over the next four years British and European leaders had to negotiate the complicated legal details of separating European and British trade law. The entire event, nicknamed Brexit as a shortened version of British exit, has shown both the complications of international trade agreements and the fact that such deals are not universally popular among everyday citizens.

THE CASE FOR GLOBALIZATION

Globalization has had positive effects in the United States. The production of goods in foreign countries with lower labor costs mean lower prices for American consumers. Televisions, clothing, cell phones, fruit, and a myriad of the things for sale in America are all less expensive because of the globalization of markets.

Economic globalization has also made it possible for American businesses to make more money selling to foreign consumers. Coca-Cola, Pepsi, McDonalds, Starbucks, Microsoft, Apple, Google, Amazon, Visa, Nike, Levi’s and many more have become successful around the world.

Improvements in communications that have accompanied increased trade mean that journalism is now global. Social media networks are global as well. Email, online messaging, voice and video calls from one side of the world to another are now common. Only a decade ago such communication was the thing of wild imagination.

Despite the negative effects critics point to, globalization has benefited the developing world. People in the Third World have found jobs producing the things people in wealthy countries want to buy. And Third World consumers now have access to the same products Americans can buy. Overall, poverty around the world has decreased. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

A McDonald’s in Thailand. Anti-globalists point to these as evidence of the destruction multinational corporations have on local culture. Globalists argue that corporations such as these increase the standard of living in Third World nations.

CONCLUSION

The world is more integrated now than it was just a decade ago, and far more integrated than it was at the end of World War II. Great nations have done much to ensure that the world’s economic health remains stable. Although the Bretton Woods system of monetary stability is gone, major institutions such as the WTO, IMF and agreements like NAFTA have increased trade, lowered prices, created new opportunities and on average, decreased poverty.

But the cost of this change is dramatic in some places. The Rust Belt is clear, ugly, evidence that some Americans are the losers in globalization. American presidents, from Nixon, Ford and Carter in the 1970s up through Trump, have all made efforts to reverse these negative effects – often to no avail. Despite the sometimes flashy efforts of the anti-globalization activists, it seems that globalization is a process that is beyond anyone’s control.

What do you think? Is it bad for America that so few of the things we buy are made here?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: Beginning in the 1970s, American manufacturing started to move overseas as businesses looked for ways to lower production costs. Although globalization has been good for many, it has not been good for all Americans and has major critics.

The 1970s are remembered as a decade of difficult economic times. The United States abandoned the Bretton Woods system of international monetary policy and the gold standard.

An oil embargo forced Americans to pay higher prices for gasoline and other goods. A combination of high unemployment, low growth and high inflation ensued. Called stagflation, American political and financial leaders were unable to turn things around.

Imported cars that were more fuel-efficient made a significant impact on the American automobile industry and imported products became familiar sights on store shelves.

Global trade was increasing and in response, some Americans looked to their government for protection. These anti-globalists oppose trade for a variety of reasons and have sometimes mobilized huge rallies and during the Trump presidency, found some success in changing trade policy.

Globalization has hurt some Americans, especially in the Rust Belt of the Northeast and Midwest where manufacturing dried up and workers lost their jobs. On the other hand, globalization has resulted in lower prices and a higher overall standard of living.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Jimmy Carter: Democratic governor of Georgia who was elected president in 1976. He served only one term and was defeated by Ronald Reagan in 1980.

Big Three: The three large American automakers based in Detroit, Michigan. Ford, Chrysler and General Motors.

Ronald Reagan: Republican former governor of California who won the presidency in 1980, defeating Jimmy Carter. Reagan was seen as a confidant, optimist who could turn around the nation’s struggling economy.

Anti-Globalization Movement: A movement of protesters opposed to many of the aspects of globalization, including the growth of large corporations, environmental impacts, worker safety and pay, cultural degradation, etc.

Social Justice Movement: An aspect of the anti-globalization movement that focuses on human rights, fair trade, worker pay and good government rather than opposing globalization in general.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Bretton Woods System: An agreement between the leading nations of the world after World War II designed to stabilize the global economy. The US Dollar was set at $35/oz. of gold and the all nations set a fixed exchange rate for their currencies.

Gold Standard: When a currency is backed by the government in gold. The currency is always worth a certain amount of gold.

Inflation: The slow rise in prices over time.

Staglfation: I situation in which there is high inflation, high unemployment, and low economic growth.

Globalization: The process of increasing connections around the world of communication and trade.

Outsource: When a company attempts to save money by moving a factory to another location where labor is cheaper, or by firing workers and hiring an outside company to do the work for less. Ford building cars in Mexico, or a store hiring a cleaning company instead of their own janitors are examples.

McWorld: Nickname for the aspect of globalization in which certain brands, such as McDonald’s become common around the world and supplant local culture with American culture.

![]()

BOOKS

No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies: Book by Naomi Klein arguing that major corporate brands are bad for the world. It is the unofficial manifesto of the anti-globalization movement.

SPEECHES

Malaise Speech: Speech by President Carter on July 15, 1979 in which he discussed the energy crisis and blamed the problem on a loss of spirit. He was criticized for being overly negative.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Rust Belt: The region of the country across the Northeast and Midwest that includes the industrial centers of Detroit, Pittsburg, Cleveland, etc. They thrived during the Industrial Revolution of the late 1800s and early 1900s, but have struggled as manufacturing moved overseas.

![]()

EVENTS

Nixon Shock: The decision by Richard Nixon to abandon the gold standard and the Bretton Woods System.

1973 Oil Embargo: OPEC agreed to limit oil shipments to the United States in 1973. This caused a crisis as fuel prices increased dramatically.

Battle in Seattle: Clash between anti-globalization protesters and police in Seattle, Washington in 1999 during the meeting of the World Trade Organization. It was the first large-scale protest against globalization.

Washington DC Protests: Anti-globalization protests in Washington, DC in 2000 and 2002 that included clashes between protesters and police.

Brexit: Nickname for the referendum and legal negotiations between 2016 and 2020 in which the United Kingdom left the European Union.

![]()

COURT CASES

Citizens United v. FCC: Supreme court case in 2010 in which the Court decided that corporations have the right to free speech and that laws cannot be passed that restrict corporations from political advertising.

![]()

GOVERNMENT AGENCIES, INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AND AGREEMENTS

World Trade Organization (WTO): International organization developed to promote free trade agreements and to serve as a judge for trade disputes between nations.

International Monetary Fund (IMF): A super-bank for the governments of the developing world to help them access funds when private banks were too weak, thus ensuring stability in global markets.

World Bank: A bank that governments in the Third World can use to finance development projects such as constructions of airports, irrigation systems or programs to fight hunger and disease.

Group of Seven (G7): The United States, Canada, United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy and Japan. With the exception of China, they are the eight largest economies in the world.

Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC): A cartel of the major oil producing nations. They attempt to work together to set production rates and the price of oil on the world market.

Whip Inflation Now (WIN): President Ford’s campaign to encourage Americans to voluntarily control spending, wage demands and price increases in order to end the stagflation of the 1970s.

Strategic Petroleum Reserve: Government owned oil located in huge tanks in Louisiana and Texas. The reserve was created in 1977 in case of emergency and could supply the nation with oil for about one month.

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA): An agreement signed in 1994 between the United States, Canada and Mexico to eliminate tariffs.

United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA): A free trade agreement signed in 2020 that updated and replaced the former NAFTA trade deal.

How has globalization evolved to modern times?

Why was it that the government was unable to help those that were affected by the events of the rust belt, especially immigrants that had worked to provide themselves a comfortable life in America?

If globalization never existed, what would a third world country’s economy look like?

Are there any areas similar to the Rust Belt in foreign countries?

Would there be any way that the USD would go back to the gold standard, and would this be a better or worse thing for the economy in America, especially with the high inflation rates as of today?

What would happen if there was another oil crisis? Would we be able to survive that since we have a better and more modern source of electricity?

How popular is the company Ford compared to other asian car companies?

Was inflation the main reason for America’s economy crashing once again?

How much inflation is too much inflation?

I think to much inflation would be considered over 6%.

What did President Carter do after his presidency?

Why are the Nation’s leaders SO focused on what happens outside of their country, and not their own country?

I wonder the same thing. Would a country be much more great if their leaders only focused on their own country?

Did the country’s morale improve when Carter’s cabinet members were asked to resign and were replaced?

Do you think that anti-globalization made the support and viewpoints of globalization stronger?

Are there still some Anti-Globalists around today in the US?

Technically, yes because today, their group is known as the Social Justice Movement. Although they don’t necessarily oppose the government, they are still working for changes that they want to actually happen, such as human rights and fair trade.

Was the anti-globalization movement stronger than the globalization movement?

What’s the process of a country asking for imports from a certain country? For example, do they file an order with a list of things they need?

I found this article that goes through the process of importing goods from other countries.

Link: https://www.score.org/resource/importing-goods-other-countries

How does today’s pandemic affect globalization?

This was a question that I had as well, about how COVID-19 has impacted globalization, as the pandemic has brought a lot of things to a stop. I found an interesting abstract that talks about this from the points of mobility, economy, and healthcare systems. It has a free version in which people can download and view, the abstract of the paper lays a very nice foundation for the rest of the article. It was here that I learned about the true strain that the pandemic has placed an unprecedented burden on the world economy, healthcare, and globalization. It was through travel, events cancellation, employment workforce, food chain, academia, and healthcare capacity. I have linked the page down below if anyone is interested in learning more.

Link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33072836/#:~:text=The%20effect%20of%20globalization%20were,%2C%20economy%2C%20and%20healthcare%20systems.&text=The%20pandemic%20has%20placed%20an,%2C%20academia%2C%20and%20healthcare%20capacity.

What effect does globalization have on the United States’ role in global economic and political matters?