TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

Christopher Columbus is often labeled the discoverer of America and remembered as the man who set off an age of wealth and glory for Spain.

However, Columbus did not discover America. Native Americans had lived there for millennia. Nor was he looking for America. In fact, for years he was convinced he had landed in Asia, which was his intended destination. His sense of the world’s size was incorrect, a fact well known in his own time.

Columbus wasn’t even Spanish. He was from Genoa, Italy and had tried to sell his idea for an exploratory voyage west across the ocean to Asia to the kings of Italy and Portugal before the Spanish finally agreed to fund his venture.

And yet, he was celebrated in story and song. His image graces postage stamps and statues. Our nation’s capital (DC is short for District of Columbia) is named for him, as is a nation in South America.

In modern times Columbus has become a flashpoint for protests. Those who decry the cultural destruction of Native American societies have used Columbus Day as a day of protest, and changed its name in many places to Discoverer’s Day or Indigenous People’s Day. The victor has become the vanquished as we apply modern moral values to historical events.

Perhaps this is much ado about nothing. Columbus lived and died 500 years ago. What’s the point of celebrating or vilifying him now? If it hadn’t been Columbus, surely other Europeans would have done what he did eventually, and other European conquerors were far more brutal than Columbus. In reality, disease was the most significant destroyer of Native American societies. And after all, what Columbus did was enormously significant in his own time, and a history-changing event.

What do you think, does Columbus deserve his honored place in history?

EUROPE, TRADE, AND THE MIDDLE AGES

The story of Europeans arriving and settling in the Americas begins long before Columbus set sail in 1492. The reasons why the king and queen of Spain decided to spend precious resources to fund his voyage at all have their roots much further back in history. To understand Europe’s Age of Exploration, we need to explore a little more deeply into what was happening there in the 1400s, and why that century was so different from the thousand years that had preceded it.

The fall of the Roman Empire in 476 CE marked the end of an era in Europe. For hundreds of years, the Romans had maintained peace in the Mediterranean region through force and had provided a unifying, centralized government. They had also provided the conditions necessary for economic prosperity. After the fall of their empire, Europe had no dominant centralized power or overarching cultural hub and experienced political, social, and military discord. These were what historians called the Middle Ages, or sometimes more poetically the Dark Ages. Centers of learning, art, and innovation moved elsewhere in the world, most notably to the Middle East where Islam emerged, and Muslim leaders built a series of expansive and thriving empires.

After the bubonic plague swept through Europe in the 1300s, Europe experienced a period of bountiful harvests and an expansion in population. By 1450, a newly rejuvenated European society was on the brink of tremendous change. Martin Luther would soon write his 95 Theses and launch the Protestant Reformation. Artists and inventors such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo were beginning a period of innovation we remember as the Renaissance.

However, most importantly for our story, Europeans were rediscovering a taste for spices from far away places in Asia. Such flavors were not entirely new in Europe. In fact, Roman leaders had openly worried that their empire would go bankrupt as Roman elites spent their wealth on exotic flavors from the East. However, trade had diminished during the Middle Ages until Christian leaders and monarchs organized the Crusades. These were a series of military escapades in which they led armies to the Middle East in an effort to wrest control of Jerusalem from Muslims. Those who made it back home, told of the delicious spices that could be found in the markets of the Middle East, and savvy European traders realized there was a fortune to be made if they could find some way to bring those flavors to market in European towns and cities.

A lively trade developed along a variety of routes known collectively as the Silk Road, to supply the demand for these products. Brigands and greedy middlemen made the trip along this route expensive and dangerous. The fall of the city of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 was a pivotal motivation for European exploration, as trade throughout the Ottoman Empire was difficult and unreliable. By the late-1400s, Europeans were anxious to find new trade routes with the rest of the world. The lure of profit pushed explorers to seek new trade routes to the Spice Islands and eliminate Muslim middlemen.

EARLY TRAVELLERS

In the 1400s, few people anywhere in the world travelled more than a few hundred miles from their home at any point in their lifetime. But this did not mean that no one ever travelled great distances, or that people knew nothing of the wider world. Indian Ocean trade routes were sailed by Arab traders. Between 1405 and 1421, the Emperor of Ming China sponsored a series of long-range sailings missions led by Zheng He. His fleets visited Arabia, East Africa, India, Maritime Southeast Asia, and Thailand. There are some historians who speculate that Zheng He may have travelled much further, perhaps even around the world. But the Ming journeys were halted abruptly after the emperor’s death, and were not followed up, as the subsequent rulers of the Chinese Ming Dynasty chose isolationism instead of economic engagement and limited maritime trade. Early 17th Century Chinese woodblock print, thought to represent Zheng He’s ships

Early 17th Century Chinese woodblock print, thought to represent Zheng He’s ships

Some European Christian embassies travelled east during the Middle Ages. Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, journeyed to Mongolia and back in the 1240s. About the same time, Russian Prince Yaroslav of Vladimir, and subsequently his sons, Alexander Nevsky and Andrey II of Vladimir, traveled to the Mongolian capital. Though having strong political implications, their journeys left no detailed accounts. Other travelers followed, like French André de Longjumeau and Flemish William of Rubruck, who reached China through Central Asia. From 1325 to 1354, a Moroccan scholar from Tangier, Ibn Battuta, journeyed through North Africa, the Sahara desert, West Africa, Southern Europe, Eastern Europe, the Horn of Africa, the Middle East and Asia, having reached China. In total, Ibn Battuta was probably the most widely travelled person in the world in his time.

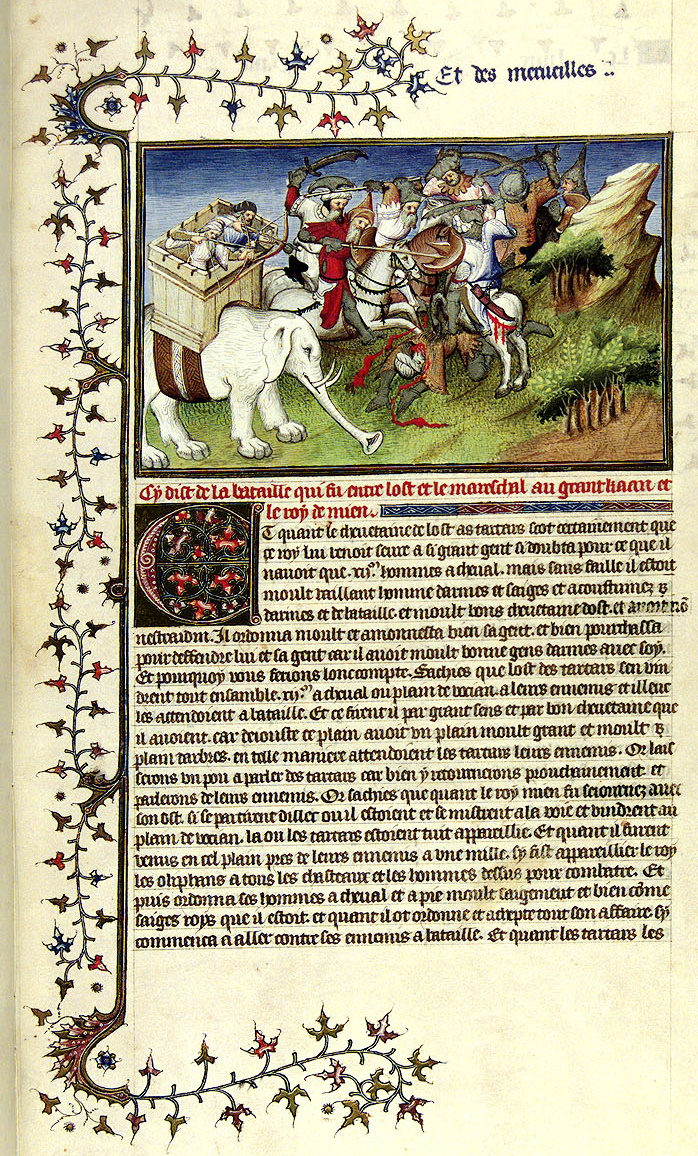

Despite the fact that others came before and probably covered more miles, Marco Polo, a Venetian merchant is the most influential of all of the people who spent years travelling in the Middle Ages, because it was Marco Polo who wrote a book that was widely available in Europe. His travels are recorded in Book of the Marvels of the World, (also known as The Travels of Marco Polo). Filled with some truths and a great deal of fiction, Marco Polo’s book told of meeting the Mongolian emperor and of the products available in Asia. He inspired Christopher Columbus and many other travelers. A page from Marco Polo’s Book of the Marvels of the World

A page from Marco Polo’s Book of the Marvels of the World

NORSE IN AMERICA

The Vikings, a group of Norse from Southern Scandinavia, are thought to be the first European explorers to arrive in North America. They sailed to what is now Newfoundland, on the far eastern end of modern Canada over 500 years before Columbus. Historical and archaeological evidence tells us that Norse people established colonies in Iceland, Greenland, and at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland.

Leif Erikson was an Icelandic explorer considered by some as the first European other than the Vikings on Greenland, to land in North America. According to the Sagas of Icelanders, Leif was the son of Erik the Red, who was the founder of the first Norse settlement in Greenland. Leif established a Norse settlement at Vinland, tentatively identified with the Norse L’Anse aux Meadows on the northern tip of Newfoundland in modern-day Canada. Later archaeological evidence suggests that Vinland may have been the area around the Gulf of St. Lawrence and that the L’Anse aux Meadows site was a ship repair station.

Unlike the more well-established settlements in Iceland and Greenland, however, continental North American settlements were small and did not develop into permanent colonies. While voyages, to collect timber for example, might have stretched as far south as modern-day New York and are likely to have occurred for some time, there is no evidence of enduring Norse settlements on mainland North America.

The Norse colony in Greenland began to decline in the 1300s, and it is probable that the settlements were defunct by the time Columbus set sail in 1492. Several theories have been advanced to explain the decline, such as the Little Ice Age, disunity within the Viking civilization due to the emergence of a unified Christian kingdom in Norway, and a series of devastating bouts of epidemic disease in Europe.

THE EUROPEAN AGE OF DISCOVERY

By the middle of the 1400s, Europeans, led by sailors from Italy, Portugal and Spain were looking for new routes to Asia. Their quest was aided by a collection of new innovations. Prior to the 1400s, Europeans largely relied on a ship known as the galley. Although galleys were fast and maneuverable, they were designed for use in the confined waters of the Mediterranean, and were unstable and inefficient in the open ocean. To cope with oceanic voyages, European sailors adapted a ship largely used in the Baltic and North Sea, which they improved by adding sail designs used in the Islamic world. These new ships, known as caravels, had deep keels, which gave them stability, combined with lateen sails, which allowed them to best exploit oceanic winds. The Portuguese capital city of Lisbon depicted in 1572. The harbor is filled with caravels and larger galleons, a ship design developed for trans-oceanic trade after the discovery of the Americas.

The Portuguese capital city of Lisbon depicted in 1572. The harbor is filled with caravels and larger galleons, a ship design developed for trans-oceanic trade after the discovery of the Americas.

The astrolabe was a new navigational instrument in Europe, one borrowed from the Islamic world, where it was used in the deserts by camel caravans. Using coordinates via the sky, one rotation of the astrolabe’s plate, called a tympan, represented the passage of one day, allowing sailors to approximate the time, direction in which they were sailing, and the number of days passed. The astrolabe was eventually replaced by the sextant as the chief navigational instrument in the 1700s. The sextant measured celestial objects in relation to the horizon, as opposed to measuring them in relation to the instrument. As a result, explorers were able to sight the sun at noon and determine their latitude, which made this instrument more accurate than the astrolabe.

While seafaring Italian traders commanded the Mediterranean and controlled trade with Asia, Spain and Portugal, at the edges of Europe, relied upon middlemen and paid higher prices for Asian goods. They sought a more direct route. And so they looked to the Atlantic. Portugal invested heavily in exploration. From his estate on the Sagres Peninsula of Portugal, a rich sailing port, Prince Henry the Navigator invested in research and technology and underwrote many technological breakthroughs. Although he never travelled himself, his nickname in history honors the fact that many of his investments bore fruit. Portuguese sailors established forts along the Atlantic coast of Africa, inaugurating centuries of European colonization there. Portuguese trading posts generated new profits that funded more trade and exploration. Trading posts spread across the vast coastline of Africa where the Portuguese learned they could use African slaves to grow sugarcane, a product that was rare in Europe. In doing so, the Portuguese encouraged Africans to go to war against other Africans in order to capture slaves to trade for European guns and iron. By the end of the 15th Century, Portugal’s Vasco de Gama leapfrogged his way around the coasts of Africa to reach India and lucrative Asian markets.

The vagaries of ocean currents and the limits of contemporary technology forced Portuguese and Spanish sailors to sail west into the open sea before cutting back east to Africa. As they did, they stumbled upon several islands off the coast of Europe and Africa, including the Azores, the Canary Islands, and the Cape Verde Islands. They became training ground for the later colonization of the Americas.

It was while the Portuguese were colonizing coastal settlements along Africa’s Atlantic coast that feudalism was starting to fade in Europe. Nation-states began to emerge under the consolidated authority of powerful kings. A series of military conflicts between England and France–the Hundred Years War–accelerated nationalism and cultivated the financial and military administration necessary to maintain nation-states. In Spain, the marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile consolidated the two most powerful kingdoms of the Iberian peninsula. Together they led la Reconquista, a war to expel Muslim Moors from what has become the nation of Spain.

THE VOYAGES OF COLUMBUS

Educated Asians and Europeans of the 1400s knew the world was round. They also knew that while it was technically possible to reach Asia by sailing west from Europe, the Earth’s vast size would doom even the greatest caravels to starvation and thirst long before they ever reached their destination. One Venetian sailor did not believe this. Christopher Columbus underestimated the size of the globe by a full two-thirds and therefore believed it was possible to arrive in the East by sailing west. After unsuccessfully shopping his proposed expedition in several European courts, he convinced Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand to provide him three small ships, which set sail in 1492. Columbus was both confoundingly wrong about the size of the Earth and spectacularly lucky that North and South America lay in his path. On October 12, 1492, after two months at sea, the Niña, Pinta, and Santa Maria and their 90 men landed in the modern-day Bahamas. Columbus, in what is probably one of the greatest examples of self-confirmation bias in history, believed he had landed in Asia and called the land India. Even today, the islands of the Caribbean are known as the West Indies. “The Landing of Columbus” by John Vanderlyn hangs in the Rotunda of the US Capitol Building in Washington, DC. Painted in 1846, Vanderlyn’s fictionalize portrayal of Columbus’s landing looks little, if anything, like the actual event.

“The Landing of Columbus” by John Vanderlyn hangs in the Rotunda of the US Capitol Building in Washington, DC. Painted in 1846, Vanderlyn’s fictionalize portrayal of Columbus’s landing looks little, if anything, like the actual event.

The indigenous Arawaks populated the Caribbean islands. They fished and grew corn, yams, and cassava. Columbus described them as innocent. “They are very gentle and without knowledge of what is evil; nor do they murder or steal,” he reported to the Spanish crown. “Your highness may believe that in all the world there can be no better people… They love their neighbors as themselves, and they have the sweetest talk in the world, and are gentle and always laughing.” But Columbus had come for the products Marco Polo had described in his book and little were to be found in the Bahamas. The Arawaks, however, wore small gold ornaments. Columbus left thirty-nine Spaniards at a military fort to find and secure the source of the gold while he returned to Spain to great acclaim and to outfit a return voyage.

Spain’s New World motives were clear from the beginning. If outfitted for a return voyage, Columbus promised the Spanish crown “as much gold as they need” and “as many slaves as they ask.” “They would make fine servants,” Columbus reported, referring to the indigenous Caribbean people. “With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.” It was God’s will, he said.

Columbus was outfitted with 17 ships and over 1,000 men to return to the West Indies. In all, Columbus made four voyages to the New World. Until his death, Columbus continued to believe he had landed in the East Indies. Although he proved to be a poor governor of Spain’s expanding colonies in America, which spread from the Bahamas to Hispaniola, Cuba, and eventually to Mexico and beyond, Columbus is remembered as the man who connected the Old and New Worlds. Although the Norse crossed the Atlantic before him, and many other more talented leaders followed and developed Spain’s New World empire, it is Columbus who is celebrated and vilified for his first fateful voyage of 1492.

THE TREATY OF TORDESILLAS

With Columbus’s journeys and the subsequent development of Spanish colonies in America, conflict emerged between the Spanish and Portuguese. Both nations were led by Catholic monarchs, and there was a danger that they would go to war over control of global trade and lucrative colonies. They turned to the Pope in Rome to fashion an agreement to divide the world between them. In 1494, they signed the Treaty of Tordesillas. In the treaty, the Portuguese received everything outside Europe east of a line that ran 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands (already Portuguese), and the islands reached by Christopher Columbus on his first voyage (claimed for Spain—Cuba, and Hispaniola). This gave them control over Africa, Asia, and eastern South America where they developed the colony of Brazil where Portuguese remains the predominant language.

The Spanish received everything west of this line. At the time, European maps west of the treaty line were blank as they still knew almost nothing of the Americas. However, because of the Treaty of Tordesillas, Spain gained unrestricted access to most of the Americas, plus the Philippines in the Pacific, which would also eventually fall under the reign of the Spanish Empire. Of course, when the Pope divided the world, he ignored the millions of Native Americans, Africans, Filipinos, and others who would eventually fall under the rule of these two great empires.

CONCLUSION

Columbus was not the first European to arrive in America, and he did not personally oversee the destruction of Native societies. In the grand scheme of things, Columbus was actually a minor player. The powerful kings and queens of Portugal and Spain, and the economic forces of world trade probably did far more to change history than Columbus.

Yet, we gravitate toward heroes, and being the first (or at least claiming to be the first) to do something is often reason enough to raise someone up as our champion.

Quite literally, Columbus has been raised up on numerous pedestals. He is the namesake of dozens of cities, a nation, a river, a time period in history, fountains and world fairs. His likeness graces paintings in our nation’s capitol building, postage stamps, and children’s history books.

But are the works of the real man worth the praise, or have we conflated Columbus with ideas much larger than the person himself?

What do you think? Does Columbus deserve his honored place in history?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: Europeans began exploring in the 1400s in search of new routes to Asia and the goods they wanted to buy. Both Spain and Portugal were leaders in the early years, sending their ships around Africa and across the Atlantic.

Exploration of the Americas by Europeans in the 1400s and 1500s was a result of historical trends that had begun long before. Spices and products from the Far East had been novelties in Europe and highly sought after, however, due to the disruptions of trade caused by wars in the Middle East, Europeans began searching for alternative routes to find these products.

The Portuguese began exploring the coast of Africa in an attempt to find a way to sail around that continent. This is why there are numerous nations in Africa that speak Portuguese and Portuguese-speaking ports in India and China. Portuguese sailors were swept across the Atlantic in storms and landed in Brazil, which later became a Portuguese colony as well, and the only Portuguese-speaking country in the Americas.

Spain as a nation did not exist as we know it today until the 1480s when two kingdoms were united by the marriage of their king and queen. Ferdinand and Isabella not only merged their two kingdoms, but also evicted the last of the Muslims from the Iberian Peninsula and funded an expedition by Italian sailor Columbus to find a way across the Atlantic Ocean to China.

Columbus and most Europeans understood that the world was round, he was just wrong about how big it was. When he landed on an island in what is now the Bahamas, he was convinced that he had arrived in China. Altogether, Columbus made four trips to America on behalf of Spain. Although he is remembered as the “discoverer” of America, Native Americans had been living there for thousands of years. He was also not a particularly good governor and lost his job as leader of the Spanish colonies in the New World.

Spain and Portugal were both Catholic nations, and to prevent conflicts they asked the Pope to divide the world between them. The resulting Treaty of Tordesillas split the world when the Pope drew a line north to south. The Americas, except Brazil, fell to the west of the line and were given to Spain. Africa was on the east of the line. This is why most of Central and South America speak Spanish, whereas few places in Africa speak Spanish.

VOCABULARY

LOCATIONS

Silk Road: Nickname for a collection of trade routes across Asia connecting China, India, and the East Indie with the Middle East and Europe.

L’Anse aux Meadows: Norse settlement in North America in what is now the Canadian Province of Newfoundland.

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Quetzalcoatl: Feathered serpent god of the pre-Columbian Mesoamericans.

Maya: Great pre-Columbian civilization centered in southern Mexico and Central America. They built cities such as Chichen Itza but their culture collapsed before the arrival of the Spanish.

Aztec: Major Mesoamerican culture that was centered around the city of Tenochtitlan (present Mexico City) when the Spanish arrived in the early 1500s.

Inca: Pre-Columbian empire that stretched along the Andes Mountains in south America.

Pueblo: Pre-Columbian civilization that thrived in what is now the Southwest United States. They build homes out of stone and mud that were sometimes multiple stories high.

Hopewell: Pre-Columbian civilization centered around the Mississippi River. They built major huge earthen mounds and established extensive trading networks with other tribes.

Algonquian: Collection of tribes who shared similar culture and language centered in New England.

![]()

EVENTS

Middle Ages: A time period in European history between the fall of the Roman Empire and the Renaissance. It was characterized by a lack of centralized political authority and little emphasis on education.

Crusades: A series of military invasions of the Middle East during the Middle Ages led by Catholic kings from Europe who attempted to recapture the city of Jerusalem from Muslims.

![]()

TECHNOLOGY

Caravel: A ship developed in Europe that had was designed specifically for sailing in the open Atlantic Ocean.

Astrolabe: Navigation instrument developed in the Muslim world and borrowed by European sailors. It used the location of the sun to determine location.

Sextant: Instrument that replaced the astrolabe and was used by sailors in the 1700s to determine location while at sea.

![]()

TREATIES

Treaty of Tordesillas: Treaty between Spain and Portugal dividing the world. It was drafted by the Pope in an effort to avoid war between the two most powerful Catholic nations. Portugal was given Africa and Brazil. Spain received the rest of the Americas and the Philippines.

Why did the indigenous Arawaks of the Caribbean islands obey Columbus?

Why did the kings of Italy and Portugal reject Columbus’s idea of exploratory voyage to Asia? Why did Spanish queen and king agree to help him?

If Christopher Columbus believed that he landed in Asia even though he was an explorer and navigator, was there anyone else who thought the same before it was found to be the Bahamas?

how dod the educated Asians and Europeans know the world was round ?

Why didn’t we just get rid of “Columbus Day”, instead of changing the name?

Have the Norse Vikings ever gotten the same kind of honor as Columbus like a song or capital since the truth came out

Have the Norse vikings ever gotten the same honor as Columbus like a song or capital since the truth came out?

The text shows what Christopher Columbus thought about the indigenous Arawaks, but what were their thoughts on him?

Why were they so obsessed with finding new land?

What made Columbus believe that the world is small?

What happened to the Indigenous Arawaks after Columbus met them, after he said they could use them and their resource? Did he bring some people to Spain to follow through with it?

How did the Roman Empire fall

Why would Marco Polo’s travel book consist of particle truths and a huge section of myths? Would having fiction in his travel book make his traveling adventures more interesting? Are people in Europe gullible enough to be very invested in his book?

Why did the Ming dynasty choose isolationism after the emperor died? It was obvious that the emperor had wanted a sort of global trade, it would be kind of weird just to halt that just because the instigator died.

Why was it named the Silk Road and what factors made it so dangerous to travel through?

I’m curious as to how Christopher Columbus and his crew felt after sailing for two months before arriving in the New World. Were there any difficulties they had to overcome? Would there have been more efficient ways to prevent them?

What would have happened if the Portuguese did not explore the coast of Africa to try to find a way to sail around that continent?

When Columbus arrived in the Caribbean and met the Arawaks what did the native people think of him and all of the Spaniards? What did they make of the technology that Columbus must have had at the time/the items he brought? And since Columbus thought they were kind people, did he try to establish a friendly relationship with them at first before having the Spanish colonize them?

What is the Little Ice Age and how would it have affected the decline of Norse Colonies in Greenland?

What if Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand declined Christopher Columbus’s expedition proposition? Would Christopher Columbus still be well known today? Would we still count him as a part of our history? Does he deserve to have Columbia named after him?

What if Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand declined Christopher Columbus’s expedition proposition? Would Christopher Columbus still be well known today? Would we still count him as a part of our history?

Christopher Columbus discovering America seems very similar to Captain Cook discovering the Hawaiian Islands. Although, they did play a role in discovering the new land, they are celebrated for their duties even though they seemed to have done more harm than good for the people living in the place before they arrived.

Were there any more inventions that the sailors used to help sail around the sea? What was the Arawaks’ first impression when they saw Columbus?

Columbus did not originally discover America, but is labelled the discoverer of America. Although his expedition is important, he still did more bad than good.

Christopher Columbus may not have been the first European explorer to discover American land, but he does have an effect on the way Americans lived after he came along. He enabled exchange of plants, animals, ideas, trade and culture. He also brought so many diseases to people he encountered on his voyages. Regardless, he did change a way people thought, lived, and learned. In a really weird way, I do support Christopher and what he introduced to people on his voyages. He does deserve his honored place in history.

Although Christopher Columbus did do a part in Colonizing America, I agree that his role was very minor. He was just a traveler with ambitions, greed, and evil. I don’t understand why we should celebrate Columbus. Columbus wasn’t the first person arrive in America, all he did was take advantages of the indigenous people and used brute force against them. When we celebrate someone, I believe we are also celebrating the actions the person did and Columbus’s actions are not something to be celebrated.

There is no evidence of enduring Norse settlements on mainland North America, so was there a war where everything was destroyed, or they never settled there for other reasons?

Who came forward to label Christopher Columbus as the person who discovered America and along with other areas of land? It’s understandable that he was one of the few people that had something to actually back up the fact that he had “discovered” these places but he shouldn’t be named the person that “Discovered America” because there were others that had already had the land and people that had discovered and come across these places before he did.

How did Christopher Columbus convince Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand to provide him ships for his voyage? What changed their minds?

Why was Colombus proved to be a poor governor of Spain’s expanding colonies in America, even though these colonies had spread from the Bahamas to Hispaniola, Cuba, and eventually to Mexico and beyond?

Why didn’t the Norse colonize America?

he did far more things that ruined the land and it’s people than he did good therefore not deserving his title. I completely agree that it should be renamed because nothing of what he did was right .

What influenced the Pope in Rome to divide the land the way he did? Did the Pope intend to ignore the millions of Native Americans concerning the division of the land?

who started the silk road? does silk road still exist today?

The fact that Columbus is labeled under a false description when you hear his name is why he shouldn’t be honored for something he didn’t do. To me it is as if you are rewarding a medal of achievement between two different people. The result being you choose the wrong person who did nothing to deserve it, compared to someone that worked extremely hard to get it. It is just simply unfair, and the protest that has been present because of his holiday is reasonable. I agree with the fact that “Columbus Day” should be renamed as Discoverer’s Day or Indigenous People’s Day.

I also agree with your point that “Columbus Day” should be renamed as Discoverer’s Day or Indigenous People’s Day. To add on, Columbus and his men were welcomed by the Arawaks with nothing more than kindness and hospitality, but Columbus cared for searching for the materialistic things that Marco Polo wrote in his book. When Columbus found out the Arawaks had a source of gold, he became traitorous, and even offered the King and Queen of Spain the Indigenous people as slaves. He betrayed their trust, and was planning to steal vast amounts that the Indigenous people clearly owned. These details of his journey aren’t very well known, with the stated points clearly contradicting his “honored” place in history.

Why did we accept Christopher Columbus as the pinnacle of America when he didn’t discover it at all?

If Columbus did not discover America , then why do we label him as the Discoverer of America?

I think that a part of the reason why Columbus is labeled “the Discoverer of America” is because of the fact that queen Isabella and King Ferdinand of Spain were the ones who gave him ships to use. They led a very powerful nation and probably used this as an opportunity to show that they helped facilitate Columbus’ “discovering new land” which came with lots of glory and the chance of colonization. (which they loved)

What was inspiring in the book that Marco Polo wrote? Why did the Emperor want isolationism instead exploration?

He wrote the Travels of Marco Polo

What did Columbus do that makes him so popular? He is not the “Discoverer of America.” He did not have as much power compared to other people. He wasn’t from Spain and wasn’t even Spanish. Why is he so well-known and popular?

With information proving to be that Christopher Columbus did not discover America, why haven’t have we seen change? Why have we accepted this false information and still, label him as the ”discoverer of America”? Most importantly, why does this country continue to celebrate Columbus Day?

I also wonder the same thing. Since our country still celebrates Columbus day, it is engraved in people’s heads that he was “America’s discoverer.” Most people still don’t know the truth behind Columbus so we should start educating others about this event.

I think Christopher Columbus is the perfect representation of “Fake it til you make it.”