INTRODUCTION

The Greatest Generation had grown up as children and teenagers in the hardscrabble years of the Great Depression. As young adults they had fought and defeated Hitler and Imperial Japan. Then, after returning to normal life from the war, they set out to build a prosperous and stable life for their children.

These children, the Baby Boomers, entered their teenage years in the early 1960s, and in sheer numbers they represented a larger force than any prior generation in the history of the country. But to their parents’ dismay, they could not have been more different.

Some of these Baby Boomer teenagers led a social rebellion that helped to define the decade. Never more than a small minority, the counterculture proved to be hugely influential as it offered an alternative to the bland homogeneity of American middle-class life, patriarchal family structures, self-discipline, unquestioning patriotism, and the acquisition of property that had characterized their childhood in the 1950s.

These hippies rejected the conventions of traditional society. Men sported beards and grew their hair long. Both men and women wore clothing from non-Western cultures, defied their parents, rejected social etiquettes and manners, and turned to music as an expression of their sense of self. Casual sex between unmarried men and women was acceptable. Drug use, especially of marijuana and psychedelic drugs like LSD and peyote, was common. They protested America’s war in Vietnam and preached a doctrine of personal freedom.

For their parents, the generation who had fought and won World War II, the counterculture was terrifying. These teenagers who they had so carefully raised had turned their back on everything they held dear. The counterculture, as many saw it, was anti-American. They didn’t want money. They didn’t follow the rules. They were throwing away and turning their backs on America itself.

What do you think? Was the counterculture anti-American?

CONTINUING THE BEATNIK LEGACY

The 1960s counterculture formed both a continuation of earlier alternative movements and was at the same time something new. Like the transcendentalists of the 1840s, they believed that finding truth meant finding new ways of thinking and living. They looked for ideas about truth and pure living outside of the strict Christian teaching they had learned as children in the 1950s and embraced Buddhist and Hindu philosophies. One lasting legacy of their spiritual quests has been the lasting popularity of Eastern traditions like meditation and yoga in America.

Most immediately, the counterculture was an outgrowth of the Beatniks of the 1950s. Like the Beatniks they believed that mainstream society had been corrupted and they sought to separate themselves. Also, like the Beatniks they embraced drugs. The great Beat writer Alan Ginsberg became a mentor to his younger followers. However, in fundamental ways the 1960s were not a pure continuation of the 1950s. The Beat generation was cold, isolated and hard to join. They wore dark clothes and listened to jazz. The hippies were easy to copy and welcomed everyone. They embraced rock and roll and bright colors.

Perhaps most importantly, the hippies believed in social change. They joined in a wide variety of social movements including the civil rights movement in the South, the environmental movement, Cesar Chaves’s efforts to help Mexican American farm workers, the women’s rights movement, and most famously, the anti-war movement.

HAIGHT-ASHBURY AND THE SUMMER OF LOVE

Most movements need a center – a leader or a place around which people and their beliefs can concentrate. For the counterculture, that center was the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco, California.

The residents of Haight-Ashbury did not set out to become home to thousands of hippies. Rather, the counterculture found the neighborhood. San Francisco was already the home of the 1950s counterculture and in Haight-Ashbury rents were inexpensive. What made the neighborhood a real magnet for hippies, however, was drugs.

Ron and Jay Thelin’s Psychedelic Shop opened on Haight Street in 1966, offering hippies a spot to purchase marijuana and LSD. The Psychedelic Shop quickly became one of the unofficial community centers for the growing numbers of young people migrating to the neighborhood Other shops opened up nearby openly selling drugs as well as crystals, tie-died shirts, books and the various other symbols of the counterculture.

Another well-known neighborhood presence was the Diggers, a local group known originally for its street theater. The Diggers believed in a free society and the good in human nature. They hated the idea of capitalism and believed money brought out the worst in people. To express their belief, they established a free store, gave out free meals, and built a free medical clinic, which was the first of its kind, all of which relied on volunteers and donations.

The neighborhood’s fame reached its peak when it became the haven for a number of the best-known musicians of the time. The members of Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, and Janis Joplin all lived there. They not only immortalized the hippie scene in song, but also knew many within the community. Primary Source: Photograph

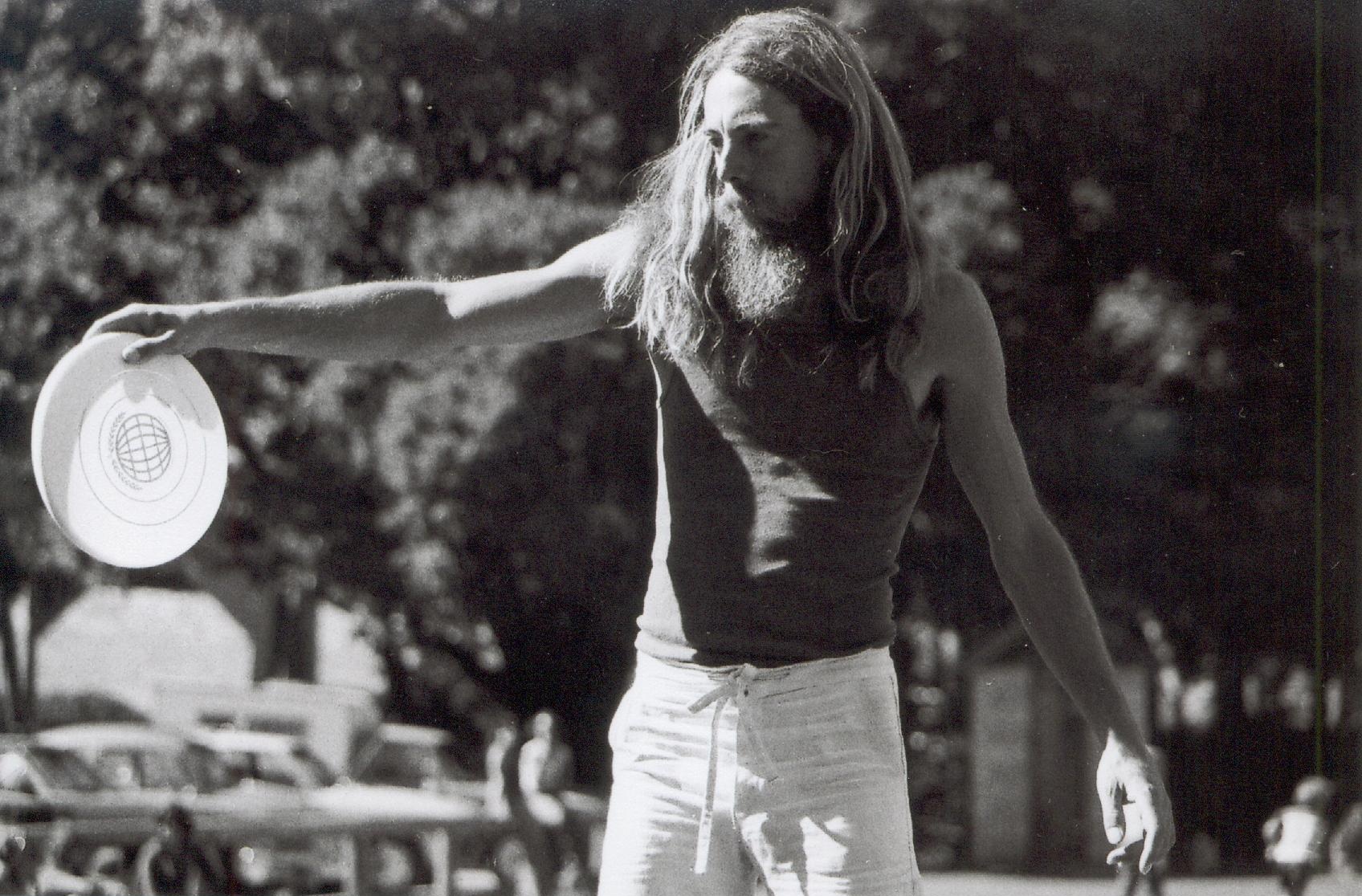

Primary Source: Photograph

The hippies both defined and symbolized the counterculture of the 1960s. Their unique fashion, music, and social outlook left an enduring mark on American culture.

Newspapers, television and magazines accelerated the concentration of the counterculture in the neighborhood. Time magazine featured a cover story entitled, “The Hippies: The Philosophy of a Subculture.” The article described the guidelines of the hippie code: “Do your own thing, wherever you have to do it and whenever you want. Drop out. Leave society as you have known it. Leave it utterly. Blow the mind of every straight person you can reach. Turn them on, if not to drugs, then to beauty, love, honesty, fun.” Coverage of hippie life in the Haight-Ashbury in the national media drew the attention of young people from all over America and in the summer of 1967, the neighborhood was overrun.

Remembered as the Summer of Love, 1967 attracted a wide range of people: teenagers and college students drawn by their peers and the allure of joining a cultural utopia, middle-class vacationers, and even partying military personnel from bases within driving distance. The Haight-Ashbury could not accommodate this rapid influx of people, and the neighborhood scene quickly deteriorated. Overcrowding, homelessness, hunger, drug problems, and crime skyrocketed. Shop owners capitalized on the crowds and sold clothing at enormous profits. The original residents and hippies who had helped create the movement criticized them for selling out.

In the end, it was too much. By August, most people left to go home to school, but the Summer of Love had changed the neighborhood. What had once been a haven for those who sought to separate themselves from mainstream America had been overrun by the pressures and problems they had hoped to avoid. The neighborhood remained important in the collective conscience, but it had changed. Never again would there be a place quite like it. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

As champions of anything alternative, hippies embraced Frisbee as a pastime. Ken Westerfield, pictured here, was especially important in organizing early competitive matches.

FREE LOVE

The counterculture gave the 1960s its most well remembered catchphrase: sex, drugs, and rock and roll. To understand the counterculture, understanding each of these three aspects is essential.

During the 1960s, especially among the hippies, a culture of free love emerged. Beginning in San Francisco in the mid-1960s, this culture of free love was propagated by thousands of hippies, who preached the power of love and the beauty of sex. For the hippies and those who tried to copy them, free love had a variety of meanings. Most obviously, it meant that the counterculture was rejecting their parents’ moral teachings about sex and marriage. In this case, “free” meant free from the rules.

Sex became more socially acceptable outside of the strict boundaries of marriage. For example, studies show that between 1965 and 1975 the number of women who had sex before marriage increased dramatically. Birth control was legalized in 1965 and abortion in 1973, both as a result of Supreme Court cases. The increased availability of birth control helped reduce the chance that premarital sex would result in unwanted pregnancies, and by the mid-1970s, the majority of newly married American couples had experienced sex before marriage.

Colleges adapted to the changing values of their students. By the 1970s, it was acceptable for colleges to allow co-educational housing where male and female students mingled freely. The days of men’s-only, or women’s-only dorms were over.

In another sense, free love had nothing to do with sex. The counterculture emerged alongside America’s growing involvement in the Vietnam War and by the time the counterculture reached its peak, the prospect of violent death in war was real for many young men. By embracing the idea of love as the opposite of hate, they could reject war. This view of free love is perhaps best captured in the lyrics of Chet Powers’ song Let’s Get Together. The chorus encourages the listeners “C’mon people now, Smile on your brother, Everybody get together, Try to love one another right now.”

The most public demonstration of the concept of free love was a love-in. Across the country, hippies gathered in parks and on college campuses to protest, listen to music, sing, meditate, share drugs, and have sex. Naturally, adults at the time were not fond of either the activities at a love-in or the name.

DRUGS

In addition to changes in sexual attitudes, many members of the counterculture experimented with drugs. Marijuana and LSD were used most commonly, but experimentation with mushrooms and pills was widespread as well. A Harvard professor named Timothy Leary made headlines by openly promoting the use of LSD.

The counterculture was particular about its drugs. They were finding a new way to live and they rejected many of the favorite drugs of their parents. For example, they avoided alcohol and sedatives which believed would deaden their minds. Instead, they embraced hallucinogenic drugs they saw as catalysts for spiritually awakening experiences. For many adherents of the counterculture, smoking marijuana, which they called dope, and using drugs like LSD or acid were part of what made them who they were.

There was a price to be paid for being different. With free love came an upsurge of venereal diseases. With LSD and acid came overdoses, drug addictions, and bad trips when drug-induced hallucinations turned into nightmares. Some of the most talented musicians of the counterculture were lost to drugs including Janice Joplin, Jim Morrison and Jimi Hendrix.

STYLE

As with other adolescent, white middle-class movements, deviant behavior of the hippies involved challenging the accepted fashion of their time. Both men and women in the hippie movement wore jeans and let their hair grow long. Both genders wore sandals, moccasins or went barefoot. Men often wore beards, while women wore little or no makeup. Hippies often chose brightly colored clothing and wore unusual styles, such as bell-bottom pants, vests, tie-dyed garments, dashikis, peasant blouses, and long, full skirts. Clothing inspired by Native American, Asian, African and Latin American motifs were popular. Much hippie clothing was self-made in defiance of corporate culture, and hippies often purchased their clothes from flea markets and second-hand shops. Favored accessories for both men and women included Native American jewelry, headscarves, headbands and long beaded necklaces. Hippies decorated their homes, vehicles and other possessions with psychedelic art. The hippies left a profound mark on American fashion. Most iconic elements of the hippie-look have been reincarnated multiple times on the runways of the world’s high fashion capitals. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Further, the bus driven by the Merry Pranksters on their trip across the country. Icons from the counterculture such as the Grateful Dead were part of the journey.

THE MERRY PRANKSTERS

Author Ken Kesey provided an important link between the Beat Generation and the counterculture of the 1960s, as well as one of its most memorable happenings. Along with his friend Neil Cassady, who had been the inspiration for the main character in Jack Karaoc’s book On the Road, they made their own cross-country journey in 1964.

When Cassady needed to visit New York after the publication of his own second novel, Kesey, Cassady and a group of friends who called themselves the Merry Pranksters hatched the idea of reversing the journey of the pioneers and traveling to New York in an old school bus. This trip, described in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test was the group’s attempt to create art out of everyday life, and to experience roadway America while high on LSD. The bus, which they nicknamed Further and decorated inside and out with psychedelic art, carried such cultural icons as the Grateful Dead and Stewart Brand who would go on to write the Whole Earth Catalogue, a guide to living a hippie lifestyle.

In an interview after arriving in New York, Kesey is quoted as saying, “The sense of communication in this country has damn near atrophied. But we found as we went along it got easier to make contact with people. If people could just understand it is possible to be different without being a threat.” A huge amount of footage was filmed on 16mm cameras during the trip, which remained largely unseen until the release of Alex Gibney’s documentary film Magic Trip in 2011.

After the bus trip, the Pranksters threw parties they called Acid Tests around the San Francisco Bay Area from 1965 to 1966. Many of the Pranksters lived at Kesey’s residence in La Honda. In New York, Cassady introduced Kesey to Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, who then turned them on to Timothy Leary, the Harvard professor and champion of psychedelic drugs. The cross-country trip of Further and the activities of the Merry Pranksters led to a number of psychedelic buses appearing in popular media over the next few years, including in the Beatles’ 1967 film the Magical Mystery Tour, the Partridge Family TV show in 1970, The Muppet Movie in 1979, and later, The Magic School Bus books and TV series.

COMMUNES

Dropping out of mainstream society altogether was a way some hippies expressed their disillusionment with the cultural and spiritual limitations of American freedom. They joined communes, usually in rural areas, to share a desire to live closer to nature, respect the earth, and escape from modern life with its obsession with material goods. Many communes grew their own organic food. Others abolished the concept of private property, and all members shared willingly with one another. Some sought to abolish traditional ideas regarding love and marriage, and free love was practiced openly.

One of the most famous communes was The Farm, established in Tennessee in 1971. Residents of The Farm adopted a blend of Christian and Asian beliefs. They shared housing, owned no private property except tools and clothing, advocated nonviolence, and tried to live as one with nature, becoming vegetarians and avoiding the use of animal products. Like the urban hippies, they smoked marijuana in an effort to reach a higher state of consciousness and to achieve a feeling of oneness and harmony.

Most communes, however, faced fates similar to their 19th Century forebears. A charismatic leader would leave or the funds would become exhausted, and the commune would gradually dissolve. In other cases, disagreements, rivalries and jealousies destroyed the communes. After all, hippies were human too.

MUSIC

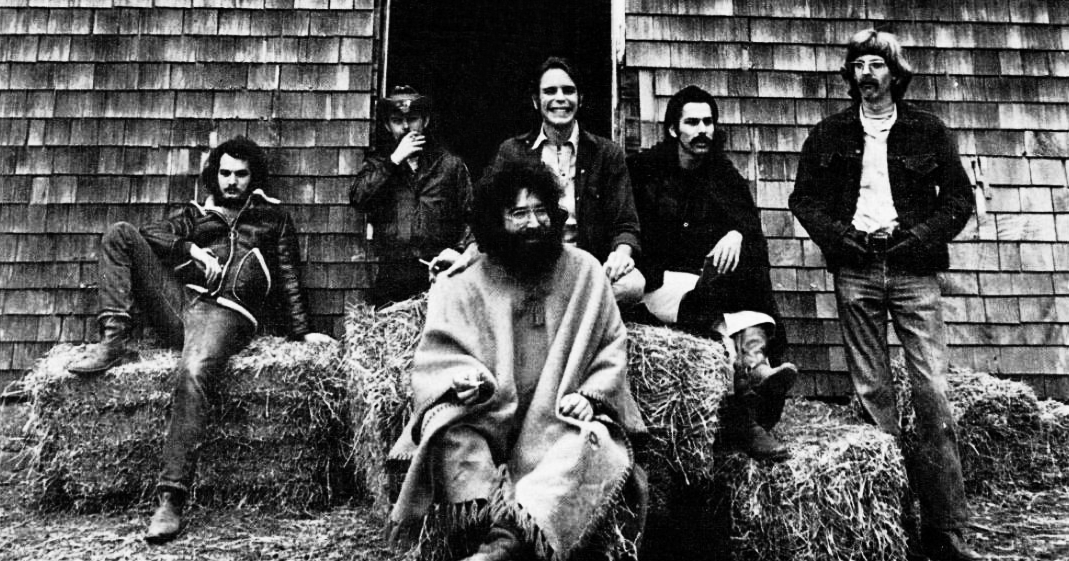

The common bond among many youths of the time was music. Centered in San Francisco, a new wave of psychedelic rock became the music of choice. Bands like the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and the Doors created new sounds with electrically enhanced guitars, subversive lyrics, and association with drugs. When the Beatles went psychedelic with their landmark album Sargent Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the music of the counterculture became mainstream. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

The members of the Grateful Dead, one of the legendary musical groups of the counterculture.

Folk rock also became popular. In a rejection of commercialism, some artists of the counterculture turned back to America’s musical roots. They popularized old songs and old instruments. Acoustic guitars, harmonicas and simple vocals became hip again. The best-known solo artist of the decade, Bob Dylan is remembered as the voice of the generation. His song, The Times They Are a-Changin’ is an encapsulation of the spirit of the times.

Other folk acts such as Janice Joplin, the Mamas & the Papas, Simon & Garfunkel, Sonny & Cher, and Peter, Paul & Mary continued the folk rock tradition.

Music, especially rock and folk music, provided the opportunity to form seemingly impromptu communities to celebrate youth, rebellion, and individuality. In mid-August 1969, one such concert near the town of Woodstock, New York became the cultural touchstone of a generation. No other event better symbolized the cultural independence and freedom of Americans coming of age in the counterculture.

WOODSTOCK

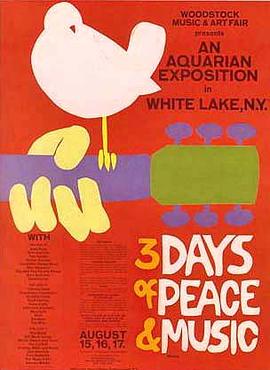

The Woodstock Music & Art Fair – or simply Woodstock – was a music festival in August 1969 on a dairy farm in the Catskill Mountains of southern New York State. It is widely regarded as a pivotal moment in popular music history, as well as the definitive nexus for the larger counterculture generation. Primary Source: Poster

Primary Source: Poster

A poster promoting the music festival at Woodstock.

The festival itself was plagued with challenges. The influx of attendees to the rural concert site created massive traffic jams. The makeshift facilities were not equipped to provide sanitation or first aid for the number of people attending. Hundreds of thousands found themselves in a struggle against bad weather, food shortages, and poor sanitation. The weekend was rainy and the concert site was a sea of mud before the event was over.

Guitarist Jimi Hendrix was the last act to perform at the festival. Because of the rain delays on Sunday, when Hendrix finally took the stage it was 8:30 Monday morning. The audience, which had peaked at an estimated 400,000 during the festival, had been reduced to about 30,000 by that point. Many of them merely waited to catch a glimpse of Hendrix before leaving during his performance. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Jimi Hendrix was one of the great innovative musicians who graced the stages of the counterculture’s concerts, and provided its defining anthem: his rendition of The Star Spangled Banner he performed at Woodstock.

Hendrix performed a two-hour set which included a psychedelic rendition of the The Star-Spangled Banner that was captured forever on film. The performance was a unique time capsule for the entire generation. Like the thousands of young Americans who loved their country but wanted it to be different from the way they knew it as children, Hendrix’s rendition of the song is both the National Anthem and at the same time radically different. His performance at Woodstock that Monday morning in a blue-beaded white leather jacket with fringe and a red head scarf is now regarded as a defining moment of the 1960s.

Despite the weather and hardships, Woodstock satisfied most attendees. There was a sense of social harmony, which, with the quality of music, and the overwhelming mass of people, helped to make it one of the enduring events of the century.

After the concert, Max Yasgur, who owned the farm that had been site of the event, saw it as a victory of peace and love. He spoke of how nearly half a million people spent the three days with music and peace on their minds despite the potential for disaster, riot, looting, and catastrophe. He stated, “If we join them, we can turn those adversities that are the problems of America today into a hope for a brighter and more peaceful future…”

ALTAMONT

If Woodstock had been a celebration of peace and love, December 6, 1969 showed a darker side of human nature. On that day, approximately 300,000 attended the Altamont Speedway Free Festival in Altamont, California. Coming less than four months after the musical, drug-filled and soggy weekend in New York, some anticipated that Altamont would be a Woodstock of the West.

The show featured many of the musical stars of the counterculture, including Santana, Jefferson Airplane, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, and the Rolling Stones. The Grateful Dead were also scheduled to perform but never took the stage.

Rolling Stone magazine wrote that the event was “rock and roll’s all-time worst day, December 6th, a day when everything went perfectly wrong.” Like Woodstock, the event was poorly organized, but unlike Woodstock, the failures led to tragedy.

Perhaps the greatest mistake was the decision to hire the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang to handle stage security. The bikers were told to keep people off the stage and were paid with $500 worth of beer. Predictably, as the bikers became increasingly drunk during the event, fights broke out, and tragically one concertgoer, Meredith Hunter, who stormed onto the stage was stabbed to death by the intervening bikers.

There were three accidental deaths as well. Two people died in a hit-and-run car accident, and one by LSD-induced drowning in an irrigation canal. Scores were injured, numerous cars were stolen and then abandoned, and there was extensive property damage.

The Altamont concert is often contrasted with Woodstock. While Woodstock represented peace and love, Altamont came to be viewed as the end of the hippie era and the de facto conclusion of 1960s youth culture. Writing for the New Yorker in 2015, pop culture critic Richard Brody said what Altamont ended was “the idea that, left to their own inclinations and stripped of the trappings of the wider social order, the young people of the new generation will somehow spontaneously create a higher, gentler, more loving grassroots order. What died at Altamont is the Rousseauian dream itself.” Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

The days of free love, experimental drug use, new age clothing, communes and flowers adorning uncut hair, were fleeting, but have left their mark on America’s identity, and certainly on the generation that grew up in the 1960s.

LEGACY

The 1960s counterculture left an interesting legacy. It is important to note that the counterculture was probably no more than 10% of the American youth population. Contrary to common belief, most young Americans sought careers and lifestyles similar to their parents. The counterculture was simply so outrageous that the media made their numbers seem larger than reality. Nevertheless, this lifestyle made an indelible cultural impact on America for decades to come.

One lasting change from the countercultural movement was in American diet. Hippies fueled the opening of health food stores that sold wheat germ, yogurt, and granola, products unheard of in 1950s America. Vegetarianism became popular.

The counterculture made drug use more acceptable, broke down cultural norms about relationships and sex, and popularized an entirely new form of music. They lent their powerful energy to the social movements of their time and altered the course of American foreign policy in Vietnam. Changes in fashion proved more fleeting but have returned in various incarnations over time.

On the other hand, the hippie dream of perfecting society by founding communes or opening free stores and of finding the greater meaning of life through drug-induced hallucinogenic experiences seems to have failed entirely. Drugs may have produced fantastical visions in the short term, but ruined lives over time. The hippie utopian experiments ran the same disappointing course as utopian movements from decades past.

So what happened to the hippies? Some grew up, got married, returned to mainstream life, got jobs, had children and left their bohemian past behind. Others never gave up the dream and moved to distant corners of America still searching for something they once felt so close to having. Now retired, the aging hippies offer a perplexing question about the wisdom of pursuing eternal youth.

CONCLUSION

When the Greatest Generation came home from World War II and started their happy families in the happy suburbs of the 1950s, they tried to build a safe, morally upstanding life for their children. They took them to church, added “under God” to the pledge of allegiance, let them watch westerns on television in which the good cowboys won, and taught them to love their country.

But to the dismay of these idealistic parents, their Baby Boomer children grew up and rejected this purified world of backyard barbeques and chaperoned ballroom dances. Instead, they did drugs, listened to rock and roll, had sex before marriage, did yoga, became vegetarians and protested the government.

In the eyes of the Greatest Generation, the children of the counterculture had rejected everything they knew to be American. For the Baby Boomers who were embracing the counterculture, they simply had a very different idea of the type of country they wanted to live in.

What do you think? Was the counterculture anti-American?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The Counterculture of the 1960s was a youth movement that focused on finding oneself and breaking social rules, especially related to love, music, fashion and drugs. It was centered in San Francisco, influenced by the anti-war movement, and fueled by new music.

The counterculture refers to a time during the 1960s when many young Americans rebelled against the traditional rules of society. The idea of rebellion was not new. In some way, they were continuing the legacy of the Beat Generation of the 1950s. However, the hippies of the counterculture were much more widely known and far more influential.

Fueled by the emergence of the Baby Boomer generation as teenagers, the counterculture, its music, art, fashion, and political ideas shaped the entire generation.

The counterculture was centered in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco. The climax of the entire movement was during the summer of 1967.

Hippies rebelled against many social norms. They experimented with new drugs, especially marijuana and LSD.

The hippies broke social rules about sex and marriage. They practiced free love and participated in love-ins.

The Merry Pranksters were a group of hippies who travelled from California to New York in an old school bus. Joined by popular musicians, they tried to demonstrate the ideas of the counterculture and recorded their experience.

Some hippies rejected modern life all together and tried to create perfect societies in communes where they shared property, and sometimes, sexual partners.

Rock and roll changed with the counterculture. Psychedelic rock became popular, as did folk rock. Music was an important part of the identity of the decade and the movement. For some, the climax of the counterculture was the Woodstock Music Festival in 1969.

The Altamont Music Festival in 1969 was the opposite of the Woodstock Festival and showed all of the dark sides of the counterculture. The organizers hired a biker gang to run security, drug use was rampant, and violence ensued.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Hippies: Young people during the 1960s who rejected traditional cultural norms and values. They listened to rock and roll, experimented with drugs, broke rules about sexual behavior. They wore bright colors, created communes, supported many of the social movements of the decade, and generally opposed the war in Vietnam.

Diggers: A group of hippies in San Francisco who hated capitalism. They opened a store where everything was free and opened a free medical clinic.

Merry Pranksters: Group of hippies led by Ken Kesey and Neil Cassady who travelled across the country in a school bus. They documented their quest to achieve the ideal hippie lifestyle in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

Timothy Leary: Harvard professor in the 1960s who promoted the use of LSD and other drugs.

Grateful Dead: Psychedelic rock group formed in the 1960s. They were led by Jerry Garcia and participated in the Merry Pranksters’ cross-country road trip.

Jefferson Airplane: Psychedelic rock band from San Francisco. They became popular during the Summer of Love.

The Doors: Psychedelic rock band led by Jim Morrison.

The Beatles: British rock band who formed in the 1950s, then came to the United States and transformed their sound during the 1960s, eventually performing psychedelic rock.

Bob Dylan: Folk rock singer after World War Ii who wrote songs such as The Times They Are a-Changin’ and is remembered as the storyteller of the generation.

Janice Joplin: Folk rock and blues singer who performed Mercedes Benz, among other popular songs of the 1960s.

The Mamas & the Papas: Folk rock group from the 1960s that performed California Dreamin’ among other hits.

Simon & Garfunkel: Folk rock duo. They performed Bridge Over Troubled Water and Sound of Silence, among other hits.

Sonny & Cher: Folk rock duo formed in the 1960s. After Sonny Bono died, Cher went on to have a long solo career.

Peter, Paul & Mary: Folk rock group formed in the 1960s. They performed Blowin’ in the Wind and other anti-war songs.

Jimi Hendrix: Innovative guitarist from the 1960s. His rendition of The Star Spangled Banner at Woodstock is famous.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Free Love: Idea popularized by the young people of the counterculture during the 1960s that sex was beautiful and being free included freeing oneself from society’s rules about sexual behavior.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Haight-Ashbury: The neighborhood in San Francisco that became the center of hippie culture, especially during the Summer of Love of 1967.

Communes: Communities formed by hippies during the 1960s in which they sought to implement their philosophy about the ideal ways to live. In some they abolished private property, in others they experimented with free love. The most famous was The Farm. Like the utopian communities of the early 1800s, they usually failed.

The Farm: Most famous of the communes of the counterculture. Located in Tennessee, its residents held a blend of Christian and Asian beliefs, rejected private property, and became vegetarians.

![]()

EVENTS

Summer of Love: Nickname for the summer of 1967 in San Francisco during which the hippie culture in that city climaxed.

Love-In: An event during the counterculture in which hippies gathered together to protest, listen to music, sing, meditate, share drugs and have sex. It was intended to be the opposite of the war in Vietnam.

Woodstock: Major music festival held in New York in 1969. It featured many of the greatest groups of the decade and is sometimes considered the climax of the counterculture.

Altamont: Music festival held in California in 1969. It was the opposite of Woodstock in many ways. It was on the opposite end of the country, was violent, and showed the worst of the counterculture.

![]()

SCIENCE

Marijuana: Drug that, like tobacco, is derived from dried leaves that are smoked. It is a mild hallucinogen and was popularized by the hippies of the counterculture. Today it has been legalized for private use in some states.

LSD: Powerful hallucinogenic drug popular in the 1960s. Hippies believed it could help a person get in touch with his or her spiritual side.

![]()

THE ARTS

Psychedelic Art: Style of art popularized by the hippies that included bold colors and patterns reminiscent of dreams or hallucinations. Tie died clothing is an example.

Psychedelic Rock: A variation of rock and roll music that used electric guitars, subversive lyrics and was played in the 1960s and 1970s by bands who were famous for experimenting with drugs. Some included the Grateful Dead and the Doors.

Folk Rock: Variation of music that became popular during the counterculture. It mixed rock and roll with traditional music and instruments. Bob Dylan, Janice Joplin, and Peter, Paul & Mary are a few performers of the genera.

![]()

BOOKS

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test: Book documenting the journey of the Merry Pranksters as they journeyed across the country during the 1960s.

Whole Earth Catalogue: A how-to book for hippies explaining such things as how to live in communes.

I find that today more people are open about free love since love nowadays shouldn’t restrict both sexual orientation and background in general.

How Is Music Today Being Influenced By Rock From Back Then?

I wonder if there are hippies now and if/how their values have evolved to fit modern thinking/morals.

Because of the fact that Hippies had such strong personal beliefs in many topics, how easy did they find it to return to normal life once they got older and had children of their own?

Why did the current generation of the time scare the previous generations so much?

Is psychedelic rock still pretty popular today?

Parents of the Boomers are like parents of our generation. They think our music is weird and that our fashion statements are too bold.

Can hippies be considered quakers?

Why didn’t they plan both concerts better, especially Altamont?

Why did they hire the Hell’s Angels to handle stage security at the Altamont festival?

What made drugs like LSD and marijuana become illegal in this day?

I notice that new hobbies, items, and styles are becoming more different from each other. Some will dress formally as possible and others will wear something that doesn’t fit the trend back then.

Why did women wear little to no makeup back then ?

back then like 1920 they didnt wanna use formal clothes like everyone else they wore baggy cothes and funky stuff but now they are doing things very diffrent its just tide eye shirts and white pants and colored glasses

Why did the Hippies started doing drugs?

The hippie code was to do whatever you want, when you want, no matter what people say. The movement quickly failed and slowly dispersed. Is “following you heart” a form of propagand?.

Trend will always die out eventually.

With the rise of the Free Love movement, how would things been different if abortion and birth control hadn’t been legalized?

did they have poc in the hippie community or were they racist to poc as well

Should counterculture be normalized or should we follow these ideal morals we tend to normalize?

Why did the people at the Altamont Speedway Free Festival think it was a good idea to hire a biker gang to be stage security and allow them to have beer while on the job?

If the people who were and went against their parent’s paths and beliefs, and that their parent’s didn’t like their choice, why did they not do anything about it? If they knew more about the world why don’t they teach their kids what is best for them so that the whole world can improve?

Why was the counterculture centered in the Height-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco?

During the time when free love is prevailed, everyone is doing the sex without any protection and that cause many people got pregnant before they marry, that is actually not really good, because they don’t even know if they will be together in their raise of the life or not.

Were the parents of the people who participated in the counter culture glad that they expressed individuality or were they disappointed?

is the LSD abuse still as severe now adays?

i think it is interesting that people considered hippies to be anti american, when their main focus seemed to be promoting love and peace. it’s interesting, and a common pattern, that people consider it bad or “rebellious” to be different or think differently.

Did the government interfere with the hippie movement?

Why did alot of hippies do drugs

Because they wanted to reach a higher state of consciousness and become in one harmony to each other

Does Hippies still exist as of today and are they active?

Why did cops not seize the drugs that the hippies had on them?

Were there any other lasting effects of the 1960s counterculture movement?

Has this generation changed throughout history

I believe so as we continue to promote these modern ideals such as being supportive the LGBTQ+ community and communities of different races or cultures. As back then in history, people were more closed off and stuck to these ideals that created a “perfect society.”

What did the rest of the world think about the hippies, did they think that they were outlandish or did they respect them?

Were there efforts to stop the counterculture of the 1960s?

Reading about the woodstock festival, it seems a lot of fun. I wish there was more festivals here. Although there seemed to be some problems it seems like a dream to see people gathered for peace and love.

Has the government ever tried to interfere with the activities of hippies?

I guess history did repeat itself with the hope that they could make utopia that is successful.

Did the hippies just abandon their families or just ignore all their rules set, and was there any age limit for being a hippy?

I don’t think hippies abandon their families entirely. Sure, some may fully disengage from any connection with those who disagree with the hippies’ activities such as wearing bright, colorful clothes and believing in “free love,” but not all people will necessarily go that far to follow their ideals. A vegetarian in an omnivorous family doesn’t mean that the vegetarian will abandon their family because they don’t have the same beliefs. The family will either decide to continue eating meat but leave only vegetables for the vegetarian, or blatantly disagree with the vegetarian’s ideals. It relies on the person with a contradicting opinion on whether or not they want to fully disassociate themselves with people that don’t agree with their ideals. Hippies disengaged themselves from mainstream American society because they did not want to be “the same” and rejected the idea of a “perfect family.” There was probably no age limit for being a hippy because anyone can forge their own opinions at any age, maybe not as early as a baby because they are still developing. However, pictures of hippies are usually teens or young adults, so maybe there is a specific age limit involved but it is not specified in the text.

Did any former hippies regret being a part of the counterculture? Were they left with any long lasting conditions from the excessive use of drugs? Did they hurt their reputation by rejecting the mainstream culture at the time?

Did any former hippies regret being a part of the counterculture? Were they left with any long lasting conditions from the excessive drugs and sex? Did they hurt their reputation by rejecting the mainstream culture at the time?

How did counterculture come to America?

How did the parents of this new generation feel about all these changes?

Were there people who were a part of the counterculture who decided to break off from it because of the consequences that came with the counterculture idea? Such as overdoses of drug intake.

Other than hippies, were there any other major groups who had advocated for social change and wanted to help the society, such as the Republicans and Democrats?

Were people opposed to the movement of the hippies? Did the hippies make that much of an impact on the world at that time?

It seems to be a common theme throughout history where a new generation’s beliefs and ideals completely oppose the previous one. Why do you think there’s such an infatuation with change and aspiring to be different? What does being “different” truly mean?

Were there any movements that went against the actions of Hippies?

How did these hippies assimilate back into “normal” American society?

How did the government react to this counterculture with the hippies?

I found an online research that goes into depth about the Woodstock Music Festival. When reading about the Woodstock Music Festival, I found it similar to the Fyre festival, so I was very interested in learning more about this festival and why it failed. This resource breaks down the festival and it elaborates on why the festival failed.

Link: https://www.history.com/topics/1960s/woodstock

Do you think that because of television and the influence of shows that forged a culture of uniformity, the counterculture is being labeled as “Anti-Americans?” If the tables were turned and the ideal American life consisted of doing drugs, having sex before marriage, would the once “American life” be considered Anti-American?

Do you think that some people joined the counterculture to commit drug-related crimes? Knowing that hippies were open about experimenting with drugs, surely some people would use it to justify their crimes?

I noticed how teens in the 1920s refused to dress like their parents and wore flappers, as well as rejecting much of their parents’ trends, similar to how hippies in the 1950s ignored their parents’ trends and did their own things instead.