INTRODUCTION

The 1950s is a decade remembered nostalgically by most of the Americans old enough to have lived through it. The economy was roaring. Conveniences that had been toys for the upper classes such as fancy refrigerators, range-top ovens, dishwashers, and convertible automobiles became middle-class staples.

Homes became affordable to many apartment dwellers for the first time and thousands of young families moved into newly built suburbs with backyard barbeques, lawns, community swimming pools and new shopping malls. The huge youth market had a music all its own called rock and roll, complete with parent-detested icons such as Elvis Presley. Disneyland, the happiest place on Earth, opened in 1955.

The pressures of the Cold War were papered over with rosy images of bliss on newly purchased television sets. Happy housewives and successful businessmen fathers tended to their dutiful children in saccharine sitcoms while cowboys in white slew cowboys in black in the pursuit of simplified justice.

Of course, not everything was as rosy as it seems at first glance. Beneath the pristine exterior, a small group of critics and nonconformists pointed out the flaws in a suburbia they believed had no soul, a government they believed was growing dangerously powerful, a lifestyle they believed was fundamentally repressed, and a society that continued to be racially segregated.

Nevertheless, the memory of the 1950s as happy days persists. Perhaps when measured against the Great Depression of the 1930s, and the Second World War of the 1940s, the 1950s were indeed a wonderful time.

It was a time when Americans loved sameness. Instilled with the fear of communism, they sought to fit in rather than stand out. America could keep them safe if they simply enjoyed its bounty. In their effort to find material comfort, to live the life they saw on television, to work and play just like their neighbors, Americans sacrificed individuality for conformity.

What do you think? Can we be happy if we’re all the same?

A BOOMING ECONOMY

The years immediately following World War II witnessed stability and prosperity for many Americans. Increasing numbers of workers enjoyed high wages, larger houses, better schools, more automobiles, and home comforts like vacuum cleaners and washing machines, which made housework easier. Many inventions familiar today made their first appearance during the 1950s.

Driven by a combination of factors, the economy grew dramatically in the years after World War II, expanding at a rate of 3.5% per year between 1945 and 1970. This dramatic growth was fueled in part by massive government spending on Cold War defense industries, but was also a result of increased consumer spending and homebuilding. During this period, many incomes doubled in a generation; a phenomenon that economist Frank Levy described as “upward mobility on a rocket ship.” The substantial increase in average family income within a generation resulted in millions of office and factory workers being lifted into a growing middle class, enabling them to sustain a standard of living once considered reserved for the wealthy.

As noted by economist Deone Zell, assembly line work paid well, while unionized factory jobs served as “stepping-stones to the middle class.” By the end of the 1950s, 87% of all American families owned at least one television, 75% owned automobiles, and 60% owned homes. By then, blue-collar workers had become the most prolific buyers of many luxury goods and services. The economy of the 1950s was dramatically different from the economy of the 1930s and early 1940s. Children who saw their parents struggling through the Great Depression and had sacrificed during World War II, found themselves surrounded by modern appliances and living in new homes. Their generation and their parents’ generation could not have lived more different lives. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

The interchange of I-15 and US 20 Idaho Falls, Idaho before completion in 1964. The interstate highway system in the United States is named after Dwight Eisenhower, who is often credited with implementing this major infrastructure project.

The booming economy and technological changes brought a growing corporatization of the United States and the decline of smaller businesses, which were not as insulated from economic swings as larger corporations that had the resources to endure hard times. Newspapers declined in numbers and consolidated. The railroad industry, once one of the cornerstones of the economy and an immense and often scorned influence on national politics, also suffered from explosive automobile sales and the construction of the interstate highway system. By the end of the 1950s, it was well into decline and by the 1970s became bankrupt, necessitating a federal government takeover. Smaller automobile manufacturers such as Nash, Studebaker, and Packard were unable to compete with the Big Three – General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler – in the new post-war world and gradually declined into oblivion.

Technological developments greatly influenced the agricultural sector as well. Ammonia from plants built during World War II to make explosives became available for making fertilizers, leading to a permanent decline in fertilizer prices. The early 1950s was the peak period for tractor sales in the United States, as the few remaining horses and mules were phased out. The horsepower of farm machinery greatly increased. An effective cotton-picking machine was introduced in 1949. Research on plant breeding produced varieties of grain crops that could produce high yields with heavy fertilizer input. These advancements resulted in the Green Revolution that began in the 1940s.

In general, farming followed the way of corporations as the industry became more concentrated and less varied. As productivity increased, so did consolidation. Small farms sold out to larger ones, leading to a reduction in the overall number of farms. Some of these former farm owners moved to towns or went to work for other farmers.

MEDICAL ADVANCES

Whereas the late 1800s had seen great works focused on collective health such as the construction of sewer systems, the 1950s was a time when medical advances focused on individual health. For example, penicillin had been used during World War II for the first time on a wide scale, saving thousands of lives from infection.

In 1948, Dr. Jonas Salk undertook a project funded by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis to address one of the most tragic diseases present in America at the time. Polio is a debilitating disease that induces paralysis, usually in the legs. It can be fatal, and those that do recover often suffer significant loss of mobility. President Franklin D. Roosevelt contracted polio when he was 39 and used a wheelchair for the rest of his life. Tragically, polio usually struck Americans as children or teenagers, just as they were their strongest.

Salk saw an opportunity to extend his research project toward developing a polio vaccine and, together with the skilled research team he assembled, devoted himself to this work for the next seven years. Over 1.8 million schoolchildren took part in the trial. When news of the vaccine’s success was made public on April 12, 1955, Salk was hailed as a miracle worker and the day nearly became a national holiday. Around the world, an immediate rush to vaccinate began.

New technologies also revolutionized surgical procedures. The first open heart operation was performed on May 6, 1953, at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia. The use of immunosuppressant drugs for the first time in the 1950s made organ transplants a viable option for the first time.

Biotechnology also underwent rapid development. The antibiotic penicillin had been discovered in England in 1939 and had saved countless lives during World War II. The production of penicillin on a massive scale in the United States transformed the pharmaceutical industry. Instead of many local druggists providing medicines to customers they knew personally, medications were manufactured on a grand scale and then shipped across the country. Another advancement was the development of a simplified and less costly process for synthesizing cortisol, a key ingredient in many medications.

Another important change that developed in the post-war decades was a shift in the way Americans paid for their healthcare. During World War II, the government set restrictions on wages. In order to attract workers, companies started offering incentives such as health insurance, and since that time, most Americans now receive their healthcare coverage from their employers.

POLITICAL STABILITY

The president during most of the 1950s was war hero Dwight Eisenhower. Ike, as he was nicknamed, walked a middle road between the two major parties. Unlike the democrats before him, Eisenhower did not want to increase federal spending by creating more programs. Neither did he want to cut programs that his democratic predecessors had enacted. This strategy, called Modern Republicanism, simultaneously restrained Democrats from expanding the New Deal while stopping conservative Republicans from reversing popular programs such as Social Security. As a result, no major reform initiatives emerged from a decade many would describe as politically dead. Perhaps freedom from controversy was the prize most American voters were seeking after World War II and the Korean War. Primary Source: Poster

Primary Source: Poster

A government propaganda poster encouraged World War II veterans to take advantage of the G.I. Bill’s tuition benefits.

THE G.I. BILL

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, known informally as the G.I. Bill, was a law that provided a range of benefits for returning World War II veterans. Benefits included low-cost mortgages, low-interest loans to start a business, cash payments of tuition and living expenses to attend university, high school, or vocational education, and one year of unemployment compensation. It was available to every veteran who had been on active duty during the war years for at least 90 days and had not been dishonorably discharged.

The G.I. Bill had a tremendous impact on America. Over half of the World War II veterans benefited from educational benefits of the law, and by 1947, nearly half of college enrollments were veterans. All told, 2.2 million veterans had used the G.I. Bill education benefits to enroll in colleges or universities, and an additional 5.6 million used the benefits for vocational training programs.

Nearly a third of all veterans accessed low-interest loans. With the post-war economic boom and very low unemployment rates, relatively few depended on unemployment benefits. These opportunities allowed many veterans to transition into the middle class and secure economic prosperity.

Veterans also fought for higher education programs more focused on practical needs, which led to increased valuing of more pragmatic programs such as engineering. A college education, and the resultant higher salary, was no longer limited to the wealthy. As more Americans earned more, they also paid more income taxes and all levels of government had more money to spend. Colleges also benefited from the influx of veterans. Increased enrollments meant more money for institutions to operate.

The G.I. Bill, as good as it was for so many people, was not designed to benefit everyone equally. Although the law itself did not specifically prohibit African Americans and other minorities from receiving loans or tuition payments, the law was written so that local governments would implement it. This meant that in the South especially, African Americans were often denied mortgage loans. Traditionally black colleges could not support the massive demands of the thousands of African American veterans and these solders-turned-students were rejected from most other universities. The overall effect was that the G.I. Bill helped lift many White Americans into the middle class, but left most African Americans behind.

THE BABY BOOM

In 1946, live births in the United States surged from 222,721 in January to 339,499 in October. By the end of the 1940s, about 32 million babies had been born, compared with 24 million in the 1930s. In May 1951, Sylvia Porter, a New York Post columnist, first used the term “boom” to refer to the phenomenon of increased births in the post-war United States. Annual births first topped four million in 1954, and did not drop below that figure until 1965, by which time four in 10 Americans were under age 20. The children born during this time are the generation we now call the Boomers.

Many factors contributed to the baby boom. Couples who could not afford to raise a family during the Great Depression made up for lost time. Returning veterans married, started families, pursued higher education, and bought their first homes. Marriage rates rose sharply in the 1940s and reached all-time highs for the country. Americans also began to marry at a younger age. The average age at first marriage dropped to 22.5 years for males and 20.1 for females, down from 24.3 for males and 21.5 for females in 1940. Getting married immediately after high school became commonplace and women were increasingly under tremendous pressure to marry by the age of 20. The stereotype developed that women were who went to college were not going to get an education, but instead to find husbands and earn a M.R.S. (missus) degree.

THE GROWTH OF THE SUBURBS

For many generations and many decades, the American Dream had promised a life in which hard work would be rewarded with material prosperity. For many, however, the notion of prosperity remained just a dream, especially during the hard times of the Great Depression and the sacrifices of the war years. However, for millions of Americans in the 1950s, the American Dream became a reality. Within their reach was the chance to have a house on their own land, a car, a dog, a white picket fence, and 2.3 children.

A large demand for housing followed from the G.I. Bill’s mortgage subsidies, and led to the expansion of suburbs. Racial fears and the desire to leave decaying cities were also factors that prompted some White Americans to flee to suburbia, and no individual promoted suburban growth more than William Levitt. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Levittown, Pennsylvania exemplified the suburbs of the 1950s.

Contracted by the federal government during the war to quickly build housing for military personnel, Levitt applied the techniques of mass production to construction of new homes. In 1947, he set out to erect the largest planned-living community in the United States on farmland he purchased on Long Island, New York.

Levitt identified 27 different steps to build a house. Therefore, 27 different teams of builders were hired to construct the homes. Each house had two bedrooms, one bathroom, and no basement. The kitchen was situated near the back of the house so mothers could keep an eye on their children in the backyard. Within one year, Levitt was building 36 houses per day. His assembly-line approach made the houses affordable. At first, the homes were available only to veterans. Eventually, though, Levittown was open to others as well. Levitt replicated his original success and there are seven Levittowns in America. Three still bear that name.

Others took Levitt’s ideas and copied them. No where was this more pronounced than in California. During the war, tens of thousands of G.I.s had passed through the state on their way to battlefields in the Pacific. They loved the beauty and the weather and moved their young families there. To greet them were opportunistic developers who were blessed with plenty of room. Suburbs exploded around cities such as San Francisco and especially Los Angeles, the American city most famous for its urban sprawl.

In one California suburb, Lakewood, developers had perfected Levitt’s methods so well that they were building 60 houses per day on average, and topped out at 110 houses completed on a single day. For old residents, bean fields were replaced by subdivisions seemingly overnight. Named for the wild spaces they replaced, these suburbs gave Americans the chance to own land, enjoy the grass of a backyard, and recapture a little slice of Thomas Jefferson’s agrarian dream.

With the ability to own a detached home, thousands of Americans soon surpassed the standard of living enjoyed by their parents. Soon, the first shopping centers and fast food restaurants added to the convenience of suburban life. America and the American Dream would never be the same. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

An early MacDonald’s in Arizona, one of the fast food pioneers that exemplified the suburban, automobile-centered life of the 1950s.

AN INCREASE IN RELIGIOUS LIFE

As the birth rate soared, families grew, and more people moved to the suburbs, the United States witnessed a boom in affiliation with organized religion, especially involving various Protestant churches. Between 1950 and 1960, church membership among Americans increased from 49% to 69%. Religious messages began to infiltrate popular culture as religious leaders became famous and numerous religious organizations were formed.

In the southern United States, evangelicals experienced a notable surge. Leaders such as Billy Graham, displacing the caricature of the pulpit-pounding country preachers of fundamentalism as stereotypes, gradually shifted. Graham began the trend of national celebrity ministers who broadcast to megachurches via radio and television. He is also notable for having been a spiritual adviser to several presidents.

Institutionalized religion became such a critical aspect of life that it came to shape major political decisions. In 1954, partly in response to the Cold War idea that communism was a threat to religion, Congress added the words “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance. Despite being a deeply religious man, President Eisenhower had never been an active member of any particular church. Sensing the mood of the country, though, he decided to be baptized in the Presbyterian Church to demonstrate his religious credentials. Since the 1950s, the religious beliefs and practices of any candidate for president have been matters of intense public interest and scrutiny in the media.

Although religion may have been an increasingly important factor in political matters, the Supreme Court acted as an important check on excess during the 1950s. A number of landmark Supreme Court cases addressed the issue of separation of church and state during the decade. The First Amendment to the Constitution states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.” In their Everson v. Board of Education decision the court decided that a New Jersey law allowing government funds to be used to pay for busses carrying students to private religious schools was unconstitutional because taxpayer money should not be used to support religious institutions. Citing Thomas Jefferson, the court concluded that, “The First Amendment has erected a wall between church and state. That wall must be kept high and impregnable. We could not approve the slightest breach.”

In 1962, the Supreme Court addressed the issue of officially sponsored prayer in public schools. In Engel v. Vitale, the Court deemed it unconstitutional for state officials to compose an official school prayer and require its use in public schools, even when the prayer was non-denominational and students could excuse themselves from participation.

TELEVISION

Perhaps no phenomenon shaped American life in the 1950s more than television. At the end of World War II, the television was a toy for only a few thousand wealthy Americans. Just 10 years later, nearly two-thirds of American households had a television and the biggest-selling periodical of the decade was TV Guide.

Network television programming blurred political, social and regional distinctions and helped forge a national popular culture, and that culture was White, Christian, righteous and centered on a family.

Television’s idea of a perfect family was a briefcase-toting professional father who left daily for work, and a pearls-wearing, nurturing housewife who raised their mischievous boys and obedient girls. Through shows such as Leave It to Beaver and Father Knows Best, television created an idyllic view of what the perfect family should look like, though few actual families ever lived up to the ideal.

Americans loved situation comedies — sitcoms. In the 1950s, I Love Lucy topped the ratings charts. The show broke new ground by including a Cuban American character, Ricky Ricardo, played by bandleader Desi Arnaz, and dealing with Lucille Ball’s pregnancy, though Lucy was never filmed from the waist down while she was pregnant.Primary Source: Photograph

A typical 1950s family enjoys television while relaxing with a soda in their suburban home. This idealized image even includes a painting of a church hanging on the wall.

America’s fascination with the West was nothing new, but television brought Western heroes into American homes and turned that fascination into a love affair. Cowboys and lawmen such as Hopalong Cassidy, Wyatt Earp and the Cisco Kid galloped across televisions every night.

The Roy Rodgers Show and Rin Tin Tin brought the West to children on Saturday mornings, and Davy Crockett coonskin caps became popular fashion items. Long running westerns, such as Bonanza and Rawhide, attracted viewers week after week.

One Western, Gunsmoke, ran for 20 years, longer than any other prime-time drama in television history. (If the Simpsons continues to be aired, it will break the record in 2019.) At the decade’s close, 30 westerns aired on prime time each week, and westerns occupied seven spots in the Nielsen Top-10 television ratings. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

James Arness stared on Gunsmoke, which ran for 20 years.

Westerns reinforced the notion that everything was OK in America. Like The Lone Ranger or Zorro, most programs of the early 1950s drew a clear line between good guys and bad guys. There was very little danger of injury or death, and good always triumphed in the end. It was a comforting genre for the early years of the Cold War.

Absent from television in the 1950s was any hint of controversy. With rare exceptions such as Desi Arnaz of I Love Lucy, minorities rarely appeared on television in the 1950s.

In addition to establishing and reinforcing social norms and creating a national popular culture, television forever changed politics. The first president to be televised was Harry Truman. When Estes Kefauver prosecuted mob boss Frank Costello on television, the Tennessee senator became a national hero and a vice presidential candidate. It did not take long for political advertisers to understand the power of the new medium. Dwight Eisenhower’s campaign staff generated sound bites — short, powerful statements from a candidate — rather than air an entire speech. Television has remained an important force in American political debate. In 2016, Donald Trump, a real estate broker and reality television star won the presidency, in part, because of his masterful use of television.

ROCK AND ROLL

The roots of rock and roll lay in African American blues and gospel that had developed over centuries and became popular in the 1920s. As the Great Migration brought African Americans to the cities of the North, the sounds of rhythm and blues (R&B) attracted White suburban teens. Due to segregation and racist attitudes, however, none of the greatest artists of the genre, who were all African American, could get much airplay on the radio.

Disc jockey Alan Freed began a rhythm and blues show on a Cleveland radio station and as his audience grew, he coined the term rock and roll. Early attempts by white artists to cover R&B songs resulted in weaker renditions that bled the heart and soul out of the originals. However, record producers saw the market potential and began to search for a white artist who could capture the African American sound.

Sam Phillips, a record producer from Memphis, Tennessee, found the answer in Elvis Presley. With a deep Southern sound, pouty lips, and gyrating hips, Elvis took an old style and made it his own. From Memphis, the sound spread to other cities, and demand for Elvis records skyrocketed. Within two years, Elvis was the most popular name in the entertainment business and had earned the nickname the King of Rock and Roll.

After the door to rock and roll acceptance was opened, African American performers such as Chuck Berry, Fats Domino and Little Richard began to enjoy broad success, as well. White performers such as Buddy Holly and Jerry Lee Lewis found artistic freedom and commercial success.

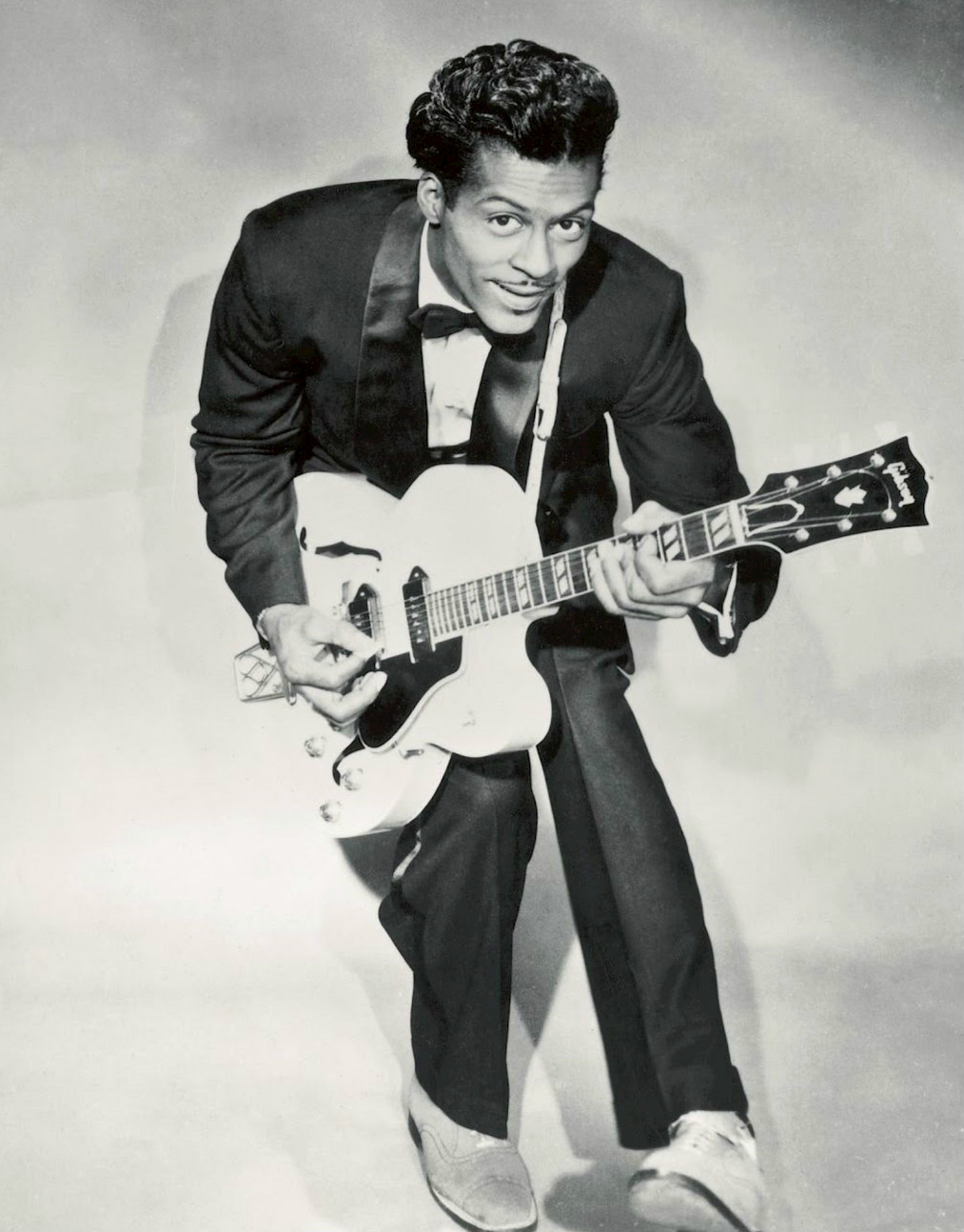

Rock and roll sent shockwaves across America. A generation of young teenagers collectively rebelled against the big band music their parents loved. In general, the older generation loathed rock and roll. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Chuck Berry was one of the pioneers of rock and roll. After Elvis Presley introduced the new form of music to White audiences, musicians like Berry and Fats Domino who had done so much to invent the genera, also found widespread success.

Teenagers found the syncopated backbeat rhythm especially suited to dance, which frightened their parents even more than the sounds emanating from their children’s radios and record players. Dance parties became the rage and American teens tuned into Dick Clark’s American Bandstand to keep up on the latest dance and fashion styles. Appalled by the new dances the movement evoked, churches proclaimed it Satan’s music.

Frank Sinatra, a great American singer who had risen to fame during the big band era of the 1940s said that rock and roll was “the most brutal, ugly, degenerate, vicious form of expression — lewd, sly, in plain fact, dirty — a rancid-smelling aphrodisiac and the martial music of every side-burned delinquent on the face of the earth.”

Because rock and roll had grown out of African American musical styles, many middle-class Whites thought it was tasteless. Rock and roll records were banned from radio stations and hundreds of schools. But the masses spoke louder than the morality police. When Elvis appeared on television on The Ed Sullivan Show, the show’s ratings soared. America’s Baby Boomers loved rock and roll, embraced it as the soundtrack of their generation, and this uniquely American musical creation went on to conquer the world.

THE EXCLUDED

The new prosperity that was the hallmark of the 1950s did not extend to everyone. Many Americans continued to live in poverty throughout the decade, especially older people and African Americans, the latter of whom continued to earn far less on average than their White counterparts in the two decades after World War II.

Between one-fifth and one-fourth of the overall population could not survive on the income they earned. The older generation of Americans did not benefit as much from the post-war economic boom, especially as many had never recovered financially from the loss of their savings during the Great Depression and were too old to go back to work. Many blue-collar workers continued to live in poverty, with 30% of those employed in industry. Racial differences were staggering. In 1947, 60% of African American families lived below the poverty level, compared with 23% of White families. In 1968, 23% of African American families lived below the poverty level, compared with 9% of White families.

Immediately after the war, 12 million returning veterans were in need of work and many could not find it. In addition, labor strikes rocked the nation; in some cases exacerbated by racial tensions due to African-Americans having taken jobs during the war and now being faced with irate returning veterans who demanded that they step aside. The huge number of women employed in the workforce in the war were also rapidly cleared out to make room for men.

In 1952, Ralph Ellison penned Invisible Man, which pinpointed American indifference to the plight of African Americans. “I am an invisible man,” he wrote. “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me…” Ellison earned the National Book Award for his work and Invisible Man continues to be ranked among the greatest novels in American literature.

African Americans were not the only minorities to suffer hardship in the 1950s. Hispanic Americans languished in urban American barrios, and the Eisenhower Administration responded with a program, derisively named Operation Wetback, designed to deport millions of Mexican Americans.

Poverty on Native American reservations increased with an Eisenhower policy designed to end federal support for tribes. Incentives such as relocation assistance and job placement were offered to Native Americans who were willing to venture off the reservations and into the cities. Unfortunately, the government excelled at relocation but struggled with job placement, leading to the creation of Native American ghettos in many western cities.

Other minorities such as Jews, Italians, and Asians also struggled to find their place in the American quilt.

THE CRITICS

As television and social pressure created an ideal American lifestyle based on White, Christian, suburban families, a vocal minority of social critics registered their dissenting voices in literature, art and action.

Most famous of the dissenters were the Beatniks. The Beat Generation developed simultaneously in the East Village in New York City and in North Beach in San Francisco. The Beatniks rejected the idealized image of America presented on television. They eschewed the suits and ties, the happy housewives, rock and roll, and phony purity of suburban life. Instead, they wore black turtleneck sweaters, jeans, sandals or Converse shoes. They wore berets and dark glasses. They frequented coffee houses. They were cool. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

One of the pioneers of bebop, a new take on jazz that emerged in the 1950s, Thelonious Monk at the piano.

While mainstream America seemed to ignore African American culture, the beats celebrated it by frequenting jazz clubs and romanticizing their poverty. In an effort to find a new way of living, they used alcohol and drugs, and experimented with new sexual lifestyles, foreshadowing the counterculture of the following decade.

The Beatniks didn’t like rock and roll, but rejected also the big band swing of their parents, which they thought had become too mainstream and too commercialized. They helped popularize bebop jazz, a new art form that was intimate, based on small quartets and quintets. Bebop emphasized improvisation and talented soloists such as saxophonists John Coltrane and Charlie Parker, trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, and pianists Thelonious Monk and Dave Brubeck, promoted jazz.

The Beatniks were not reformers. They believed that mainstream American culture was so corrupt that fixing it would be a lost cause. Like the Transcendentalists of the 1820s and 1830s, they believed that only by separating completely could they find true meaning in life. Beatnik communities thrived in New York and San Francisco, but also sprung up in Venice in Los Angeles and the French Quarter in New Orleans.

The driving force behind the Beat Generation were its writers, and the writer who first defined what it meant to be beat was Allen Ginsberg. His poem Howl, published in 1956, railed against the conformity of mainstream culture and celebrated the life of the Beatniks who sought to live life as they pleased. Most shockingly, it described drug use and both heterosexual and homosexual sex at a time when homosexual sex was illegal in almost every state.

As a result, the poem became the subject of an important court case. Copies of the poem were seized by authorities and the owner of the bookstore that first sold them was arrested. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and numerous critics spoke in defense of the poem’s literary value and the judge hearing the case ruled that it had “redeeming social importance,” setting a precedent for freedom of speech.

Another of the Beat Generation’s defining authors was Ginsberg’s friend Jack Kerouac. His novel On the Road, published in 1957, retells the wanderings of a young Beatnik in search of what Kerouac described as IT, the essential meaning of life, stripped of social rules and obligations. The protagonist’s journey echoes that of Huckleberry Finn in Mark Twain’s classic. Like Twain, and especially like Henry David Thoreau a century before, Kerouac believed that only by cutting oneself off completely from the surrounding mainstream culture could a person truly live a meaningful life.

Other writers of the Beat Generation critiqued specific aspects of mainstream culture. The notion of the white-collar, executive-track, male employee was condemned in fiction in Sloan Wilson’s The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit and in commentary in William Whyte’s The Organization Man.

Economist John Kenneth Galbraith criticized old values in his book In The Affluent Society. Galbraith argued that happiness and education were more important measures of success than the output of goods and services.

In his book The City in History, Lewis Mumford described the ideal urban setting in which growth and planning were in harmony with the environment. His critique of the new suburbs and their artificial nature was harsh. He wrote that “the suburb served as an asylum for the preservation of illusion. Here domesticity could prosper, oblivious of the pervasive regimentation beyond. This was not merely a child-centered environment; it was based on a childish view of the world, in which reality was sacrificed to the pleasure principle.”

Even singers tore into the sameness of the suburbs. In her song Little Boxes, Malvina Reynolds mocked suburban tract housing as little boxes of different colors “all made out of ticky-tacky,” which all looked “just the same.”

The booming postwar defense industry came under fire in C. Wright Mills’ The Power Elite. Mills feared that an alliance between military leaders and munitions manufacturers held an unhealthy proportion of power that could ultimately endanger American democracy, a sentiment echoed by President Eisenhower in his Farewell Address.

Even the life of teenagers growing up in the false happiness of suburbia was skewered in literature by J.D. Salinger in his novel The Catcher in the Rye.

American painters also took shots at conformity. Edward Hopper, who had made a name for himself in earlier decades, combated the blissful images of television by showing an America full of loneliness and alienation. Primary Source: Painting

Primary Source: Painting

“Convergence” by Jackson Pollock, exemplifies the abstract expressionism that swept the American art world after World War II.

In New York City, painters broke with the conventions of Western art to create abstract expressionism, widely regarded as the most significant artistic movement ever to come out of America. Abstract expressionists, such as Willem de Koonigh, Hans Hoffman, Mark Rothko, and Jackson Pollock, sought to express their subconscious and their dissatisfaction with postwar life through unique and innovative paintings. For them, the physical act of painting was almost as important as the work itself. Jackson Pollock gained fame through action painting, the act pouring, dripping, and spattering the paint onto the canvas. Rothko covered his canvas with large rectangles, which he said conveyed “basic human emotions.”

While the 1950s cinemas were mostly home to the typical Hollywood fare of Westerns and romances, a handful of films shocked audiences by uncovering the dark side of America’s youth. Marlon Brando played the leather-clad leader of a motorcycle gang that ransacked a small town in The Wild One. The film terrified adults but fascinated kids, who emulated Brando’s style. 1955 saw the release of Blackboard Jungle, a film about juvenile delinquency in an urban high school. It was the first major release to use a rock and roll soundtrack and was banned in many areas both for its violent portrayal of high school life and its use of a multiracial cast of lead actors.

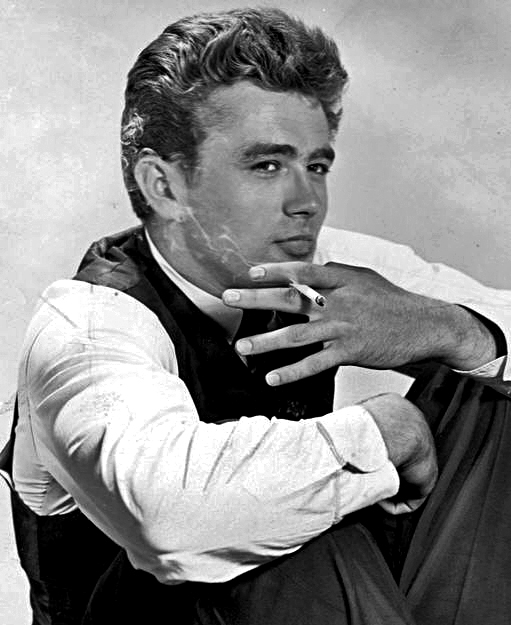

Perhaps the most controversial and influential of these films is 1955’s Rebel Without a Cause. Another film about teenage delinquency, Rebel was not set amid urban decay, but rather in an affluent suburb. Ironically, the film made it clear that the failure of those very families was to blame for the main characters’ troubles. Once again, parents were outraged, but the message could no longer be ignored. Juvenile delinquency was no longer a problem for the lower classes. It was lurking in the supposedly perfect suburbs. The film earned three Academy Award nominations and propelled James Dean to posthumous but eternal stardom.

Perhaps ironically, the majority of the Beatniks and critics of affluence and conformity where the same White middle class Americans who were enjoying the nation’s newfound prosperity the most. Lower classes, blue-collar workers, and minorities who had sacrificed during World War II to demonstrate their patriotism and prove that they deserved a place at America’s table rejected the growing counterculture. For them, prosperity had finally arrived after generations of waiting and they saw no reason not to embrace it.

Although the Beatniks and social critics of the 1950s would pave the way for a much larger counterculture movement in the next decade, they were a tiny fraction Americans overall. Most of the new, prosperous middle class families were content to live out their days in the sameness of their suburban homes, try to enjoy happy days and live up to the models of perfect families found on television. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

James Dean symbolized rejection of the 1950s ideal young man. His performance in “Rebel Without a Cause” shocked parents, inspired teenagers, and won critical acclaim.

CONCLUSION

Despite what the critics may have said, most Americans were quite happy with their lives during the 1950s. New homes in the suburbs and the roaring economy gave them a chance to enjoy a life that had eluded their parents. For the first time in a long time, the basic needs of nearly every American were being met.

The saying “a rising tide lifts all ships” was true in the 1950s. Although the members of the lower class and minorities were often excluded from the very best opportunities, they were not excluded entirely. Many who had previously only expected a future of poverty were able to join the ranks of the middle class.

At last, happiness seemed to have arrived. The only price to pay for contentment was to leave individuality behind. Those who sought prosperity and bliss had to conform, and conform they did. Millions of Americans bought into the idyllic life they saw on television. They bought the products advertisers told them they had to have and wore the clothes the advertisers told them to wear.

But is this really happiness? Or as the Beatniks and their fellow critics proclaimed, is conformity just a way of hiding from hard truths?

What do you think? Can we be happy if we’re all the same?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The 1950s are remembered as a good time for most Americans. The economy was doing well and people were happy to have new houses, cars, and modern appliances. However, there were underlying problems for some groups who were left out of these happy days, and because happiness also meant conformity.

Most Americans have happy memories of the 1950s. During the 1950s, the economy boomed. Middle class and blue-collar workers all did well. For the first time ever, most Americans could afford houses, cars, and new inventions like televisions. The interstate highway system was built, encouraging automobile purchasing, and the use of fertilizers led to abundant harvests. New advances in medicine helped people live longer.

Politically, the 1950s were stable. Eisenhower was president and he kept the government from spending too much, while also not reducing popular programs like Social Security. Although it was the height of the Cold War arms race, Eisenhower ended the Korean War and kept the nation out of any hot conflicts.

The G.I. Bill helped veterans of World War II buy houses and attend college. For the first time, both became common. Those same veterans came home and started families. Their children, the Baby Boomers, are one of the nation’s largest generations ever. To house these families, suburbs were built. Cities grew, shopping malls, and fast food restaurants sprung up. It was a time of huge population growth in California.

People in the 1950s became more religious. More Americans went to church. However, the Supreme Court also limited the influence of religion in schools, banning school prayer for example.

In the 1950s, there was tremendous pressure for people to live up to an ideal. Families were supposed to have married parents, with a dad who worked and a mom who stayed home to raise polite children. They were supposed to have a house in the suburbs and a car.

Television was new and promoted this idealized version of family. Sitcoms were popular. Westerns were also popular in which good could always triumph over evil.

Rock and roll was new in the 1950s. Although based on African American traditions like rhythm and blues, it was first popularized by Elvis Presley.

Not everyone enjoyed the prosperity of the 1950s. The elderly, women, African Americans and other minorities did not benefit from the G.I. Bill.

The Beatniks rejected the conformity of the 1950s. Centered in San Francisco and New York City, they preferred a new form of jazz called bebop and criticized mainstream culture. The Beat Generation created some of the best literature of the 1950s. Those who did not want to conform also popularized abstract expressionism, a new style in art. Some movies of the 1950s similarly portrayed the darker side of society.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Blue-Collar Workers: Workers who earn a living from their labor. They include custodians, construction workers, and factory workers.

Dr. Jonas Salk: Doctor who discovered a vaccine to prevent Polio.

Dwight Eisenhower: Republican president during the 1950s. He championed Modern Republicanism. He did not want to increase federal spending but also did not cut New Deal programs. He oversaw the arms race during the Cold War, but his presidency is remembered as a time of peace and economic growth.

Baby Boomers: The largest generation of Americans. They were born between 1945 and 1965. They were the children of the Greatest Generation and grew up during the 1950s, were teenagers and young adults during the 1960s, fought in Vietnam, and are the parents of Generation X. Most of them are now retiring.

William Levitt: Entrepreneur who developed methods for quickly building suburbs with inexpensive housing.

Billy Graham: Celebrity Christian minister during the post-World War II era. He broadcast his sermons on television and advised multiple presidents.

Elvis Presley: The “King” of Rock and Roll. As a White musician who had access to radio airtime, he popularized the new musical style in the 1950s when African Americans who had developed it had less public exposure.

Ralph Ellison: African American author of Invisible Man. He won the National Book Award for his writing about indifference toward African Americans.

Beatniks: A group of social critics during the 1950s, based in New York City and San Francisco, or questioned mainstream culture. The embraced jazz rather than rock and roll, wore dark clothes, drank coffee rather than alcohol, and popularized the idea of “cool.”

John Coltrane: Great saxophonist of the bebop jazz era. He often recorded with other great musicians of the era.

Charlie Parker: Great saxophonist of the bebop jazz era. He was nicknamed “Yardbird” or just the “Bird.”

Dizzy Gillespie: Great saxophonist of the bebop jazz era.

Thelonious Monk: Great pianist and composer of the bebop jazz era.

Dave Brubeck: Great pianist of the bebop jazz era. His most famous song was Take Five.

Allen Ginsberg: Beat generation author of the poem “Howl.”

American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU): Organization that provides lawyers to defend people they believe have had their basic rights violated. For example, they defend freedom of speech cases and in the 1920s, helped defend John Scopes.

Jack Kerouac: Beat Generation author of “On the Road”

J.D. Salinger: Author of “The Catcher in the Rye” who wrote about false happiness in the suburbs of the 1950s.

Willem de Koonigh: Dutch American artist who helped popularize Abstract Impressionism after World War II.

Hans Hoffman: German American artist who helped launch the Abstract Impressionist era after World War II.

Mark Rothko: American artist of the Abstract Impressionist era who was famous four painting large rectangles he say conveyed “basic human emotions.”

Jackson Pollock: Famous artist of the Abstract Impressionist era who is famous for splashing paint wildly over large canvasses. He called it his “drip” technique.

Marlon Brando: Movie star of the 1950s. He played a motorcycle gang leader in The Wild One, the first major motion picture to feature rock and roll in its soundtrack.

James Dean: Academy Award winning actor from the 1950s who portrayed a troubled teenager in Rebel Without a Cause, a film that stood in contrast to the utopian image many held of suburban life in the 50s.

Edward Hopper: Artist of the 1950s who painted scenes that challenged the ideal images of life in the 1950s. His painting “Nighthawks” is the most famous.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Middle Class: The large group of Americans who are not wealth or poor, but are able to live comfortably on the money they earn from their work.

Corporatization: The process by which small businesses close during difficult economic times and larger, more financially resilient companies survive and take their place in the economy.

Green Revolution: A change in agriculture in the 1940s and 1950s in which selective breeding, the use of fertilizer, and other scientific advancements led to a tremendous increase in food production.

Consolidation: The process of combining small businesses or farms into larger ones.

Modern Republicanism: A political philosophy during the second half of the 1900s in which Republican politicians did not increase government spending, but also did not cut popular New Deal programs such as Social Security.

Mortgage: A loan to purchase a house or condominium.

Tuition: The cost of a college education.

American Dream: Persistent myth in America that hard work and ingenuity will result in upward social mobility. In the 1950s, the goal was a house in the suburbs, a family with children, a car and a dog.

Urban Sprawl: The spread of cities, especially suburbs, into rural areas. This process usually involves wasted land in which large parking lots divide buildings or large yards separate homes. It necessitates a car-based culture in order to get around.

1950s Ideal Family: Family structure that includes a father who goes to work, a mother who stays home to care for the house and children, and two or three children. This image was perpetuated in early television in shows such as Leave It to Beaver and Father Knows Best. It is heavily influenced by the Cult of Domesticity.

![]()

COURT CASES

Everson v. Board of Education: 1947 Supreme Court case in which the Court concluded that taxpayer dollars cannot be spent to support private schools because it violates the First Amendment separation of church and state. In the particular case, public school busses were transporting students to a religious school.

Engel v. Vitale: 1962 Supreme Court case in which the Court concluded that public schools may not require students to participate in prayers because it violates the First Amendment separation of church and state.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Interstate Highway System: A network of limited-access, high-speed roads built to connect major cities beginning in the 1950s.

Suburbs: The neighborhoods that grow up around a large city. They grew rapidly in the 1950s.

Levittown: A suburban city built by William Levitt. The first was in New York. Eventually six more were built.

Shopping Center: Designations in which many stores are concentrated together in one building, usually around a few department stores. These developed in the suburbs in the 1950s.

Fast Food Restaurant: A type of restaurant with a limited, inexpensive menu in which food would always be cooked waiting for customers. They developed during the 1950s as part of the growth of suburbs.

![]()

SCIENCE

Polio: Debilitating neurological disease that produces paralysis in the legs. A vaccine was discovered by Dr. Jonas Salk.

Penicillin: Antibiotic that was discovered in 1939 and prevented tremendous numbers of deaths beginning in World War II.

![]()

LITERATURE

Invisible Man: Ralph Ellison’s award winning novel about the plight of African Americans in the 1950s.

Howl: Allen Ginsberg’s famous poem that helped define the Beat Generation. It was the subject of an important freedom of speech court case when authorities tried to confiscate copies from a bookstore due to its homosexual subjects.

On the Road: Book by Jack Kerouac that helped define what it mean to be Beat during the 1950s.

The Catcher in the Rye: Novel by J.D. Salinger exposing the false happiness of life in the suburbs of the 1950s.

![]()

ENTERTAINMENT

I Love Lucy: Popular 1950s Sitcom starring Lucille Ball.

Westerns: Category of television show that features heavily stereotypical cowboys, outlaws, Hispanics, Native Americans and other characters from the West.

Gunsmoke: Television western that ran for 20 years.

Rhythm and Blues (R&B): Musical style popularized by African Americans in the cities of the North. It attracted White suburban teenagers and gave rise to rock and roll when White musicians used it as the basis for their own versions.

Rock and Roll: Musical style that developed in the 1950s. It was originally based on R&B.

Dick Clark’s American Bandstand: Popular television program in the 1950s that promoted new rock and roll acts and dances.

The Ed Sullivan Show: Popular television show in the 1950s that featured new musicians. The Beatles famously played this show when they first arrived in the United States.

Bebop: Form of jazz that developed in the 1950s. Unlike the big band swing of the 1930s and 1940s, this new style was performed by small quartets and quintets and emphasized improvisation.

Abstract Expressionism: Art style popularized after World War II. Artists in this style expressed their dissatisfaction with postwar life by making the act of painting more important than the work itself. Jackson Pollock’s wild splashes of pain on large canvasses are the most famous.

![]()

LAWS & GOVERNMENT PROGRAMS

G.I. Bill: Nickname for the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act. Passed in 1944 it gave money to veterans to attend college or buy houses. It had a tremendous impact on the education levels of adult Americans and also led to a boom in suburban development.

Operation Wetback: Government program during the 1950s to deport millions of Mexican Americans who had come to the United States, mostly as farmworkers.

Do the majority of Americans still live the American dream?

Are artists of all degrees still being recognized by people?

I wonder if there is a difference in the general opinions about the American dream within and outside of the US.

Did the baby boom have any unexpected consequences? Like an increase in poverty levels or unemployment for the more poorer families?

Is the idea of a “perfect family” still ideal today?

The idea of a perfect family back then is different than now but people nowadays wouldn’t mind living as the “perfect family” shown back then. Though it is not depicted as the ideal family now, it is still not a bad life to live.

Were the beatniks the only counter culture during the 50s?

Did architectures make a better plan for building houses then Levitt’s one?

Why did people be against some of the new topics like Rock and Roll.

I think they were against the ideas of new topics like Rock and Roll because it wasn’t what they were used to, and often things like Rock and Roll Music was accompanied with rebellious behavior.

Why wasn’t the media able to spread awareness about the American Minority groups that were rejected from the G.I. Bill ?

The 1950s were similar to the 1880s-1920s where people from around the world started to immigrate to America and live the American dream. Back in the 1880s-1920s, after the civil war, African Americans were still being discriminated against (like segregated schools) but were given more opportunity. They were still discriminated against in the 1950s with the G.I. Bill. There still is a pattern today because African Americans are still fighting for equal rights. Also many European immigrated to America back in the late 1490s-1763 for religious freedom and in the 1950s-1960s more people became religious and had church memberships.

Would there ever be another ” boomer ” time in the future ?

Why is that the word ” boomer ” is so popular nowadays ?

why did the American believe christianity in the first place?

Why did people still “create” babies when their financial situation was bad?

Did many marriages fail, due to the societal expectation to get married back then?

Did many marriages fail, due to the societal expectation to get married after high school back then?

Similar to the boom in the economy post WWII, would it make sense for there to be similar upward trend in the economy after the pandemic?

people only judged rock and roll because it was from african americans

Is the American Dream an ideal moral we should still follow today?

Why did people have to marry each other in their early 20s?

How were the POC and Women treated during the 1950’s?

Why were so many Americans help up to this ideal where one needs the perfect family and a perfect home? did individuality not matter?

In the past, people worried about the population increase too fast. Now people is worry about the population decrease too fast.

How does Satan correlate to Rock and Roll

a pattern i see in history is that america benefits off of african american culture but refuses to recognize or represent the people who created it. black artists did not get to be recognized as mainstream, but white artists who captured the “african american sound” did.

It seems that every time the US is wounded they always recover and evolve better. they see the mistake they made and try to fix it to make the economy better, but not all of the solutions work, so they have to try harder.

Dr. Jonas Salk Making A Vaccine For Polio Reminds Me Of Corona Virus Getting The Vaccine🤔

who came up with the word boomer

In the section “The Baby Boom” Sylvia used the term “boom”, which refers to the increasing numbers of births. I think that is why they were called “Boomers”. I am not sure.

why do people now days use boomer

After criticism and dissatisfaction were stated out to the public was there anyone or anything who tried to fix these problems that these artists said?

The only pattern that i’ve seen when i was reading this article was the music. Since elvis presley was known by a producer in Tennessee and many African Americans, now that music was formed, nothing really has changed in the music industry in this century.

How come everyone did not deserve a same amount of benefit when the G,I bill was passed out?

How much of a role did the G.I. Bill’s limited benefits among older people and especially minorities play into the artistic movements of genres like Bebop Jazz and Rock and Roll? What effects, if any, did Eisenhower’s lack of major action in his time in office have on the growing counterculture?

Why did many parents in the 1950s hate rock and roll?

Cause most families are christians, but Rock and Roll are viewed as Satanic.

Rock and Roll was loud and was different from other genres of music like jazz and country music.

If baby boomers were a way of recoverment from the Great Depression, did they suffer as well or did they live a better life?

Were there government-funded programs for those in poverty?

What do the parents of the Beatniks think about their children? I mean if the parents are conservative but have a beatnik child.

Is there a reason as to why the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 is called the G.I. Bill?

It is interesting how TV was all the rage back then, but now it is a dying medium. The new generation doesn’t really watch TV like many do back then. They don’t really watch network TV either, they mostly enjoy other mediums through their phones.

Dr. Jonas Salk making a vaccine for Polio reminds me of Corona Virus getting the vaccine

Why was Dwight Eisenhower considered a war hero?

He wanted to spread his political values as a republican and wanted to contain the spread of communism. He also wanted to reduce federal delicts.

I noticed that many groups in history use clothes to create their own identity and reject mainstream culture. The Beatniks wore black turtlenecks, jeans, and converse shoes in order to reject the normal clean suit and tie. Zoot suits were worn by African Americans, Filipinos, and Mexicans in order to embrace their identity and own a unique style.

I noticed that many groups in history use clothes to create their own identity and reject mainstream culture. The Beatniks wore black turtlenecks, jeans, and converse shoes in order to reject the normal clean suit and tie. Zoot suits were worn by African Americans, Filipinos, and Mexicans in order to embrace their identity and make a statement.

If families didn’t uphold the image of a “perfect family,” would they be judged for it?

If families didn’t uphold the image of a “perfect family,” then they would be judged for it because of the idea that we should be alike to one another rather than expressing our uniqueness. Like the segregation era, people with colored skin were mistreated by Whites due to just one attribute: their appearance. People often don’t accept those who are “different” because they speculate that everyone who does not look or act similarly to them is considered “dangerous” or “lower-class.” Families who don’t live up to the ideal as seen on television would be criticized for not conforming to the norms of “their society.” Thus, “imperfect families” would be mistreated or ignored by those who live up to the ideals shown on television. This can be compared to a phenomenon of “peer pressure,” where someone would change themselves just to blend in with their community.

Most families were happy during the 1950s, but what made children happy? Not much technology was here during this time, and so what did children do to entertain themselves?

Who came up with the name Boomers?

Were privileged people aware of the people who were excluded from all the postwar luxuries or were they distracted by their seemingly “perfect” life?

Were there many teens that did not listen to rock and roll, or did not participate in absurd things?

I think that there definitely were many teens who didn’t listen to rock and roll and instead wanted to live a life like their parents.

yeah , I agree with erica . They did ban it from a lot of radio stations and schools so that could have been a reason why also.

Were the African Americans and other minorities living in the North able to receive the benefits of the G.I. Bill?

I found this online resource that explains the G.I. Bill or officially known as the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944. It talks about the GI bill now and what happened to the GI Bill after 9/11. This online resource is great for anyone who wants to learn more about the GI Bill.

Link: https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/gi-bill

What other groups emerged after the Beatniks? (e.g hippies?)

Why were they called the “Beat Generation” or “Beatniks”?

“Its adherents, self-styled as “beat” (originally meaning “weary,” but later also connoting a musical sense, a “beatific” spirituality, and other meanings) and derisively called “beatniks,” expressed their alienation from conventional, or “square,” society by adopting a style of dress, manners, and “hip” vocabulary.

Link: https://www.britannica.com/art/Beat-movement

Why didn’t the President during the time not make sure the G.I. Bill applied to everyone, like African Americans and minorities?