TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

Civilization works if people follow rules. No nation or society can function if its people run amuck and do as they please. Some rules are simply a matter of being polite. We hold the door open and say please and thank you. Other rules are laws. We cannot steal or commit murder.

In some cases, our government tries to make us to be good by making bad behavior costly. Sin taxes that make cigarettes expensive, for example, are a way of society discouraging smoking. However, is this a good idea? Can we make people good by making bad behavior illegal? And what happens when we extend this idea to thoughts. Can we make destructive thoughts illegal?

What do you think? Can laws make us moral?

RACISM IN THE 1920s

Foreigners had been flowing into Ellis and Angel Islands for years. African Americans had been moving north for jobs and promoting new ideas about equality and justice. Many White, Protestant, Americans, especially in rural areas, had a sense that their nation, sense of identity, and way of life was under siege. This sense was clearly reflected in the popularity of the 1915 motion picture, D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation. Based on The Clansman, a 1915 novel by Thomas Dixon, the film offers a racist, White-centric view of the Reconstruction Era. The film depicts White southerners made helpless by Northern carpetbaggers who empower freed slaves to abuse White men and violate women. The heroes of the film were the Ku Klux Klan, who saved the Whites, the South, and the nation. While the film was reviled by many African Americans and the NAACP for its historical inaccuracies and its maligning of freed slaves, it was celebrated by many Whites who accepted the historical revisionism as an accurate portrayal of Reconstruction Era oppression. After viewing the film, President Wilson reportedly remarked, “It is like writing history with lightning, and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.” Wilson, a Virginian, was renowned for his racist views.

The Ku Klux Klan (KKK), which had been dormant since the end of Reconstruction in 1877, experienced a resurgence of attention following the popularity of the film. Just months after the film’s release, a second incarnation of the Klan was established at Stone Mountain, Georgia, under the leadership of William Simmons. This new Klan now publicly eschewed violence and received mainstream support. Its embrace of Protestantism, anti-Catholicism, and anti-Semitism, and its appeals for stricter immigration policies, gained the group a level of acceptance by nativists with similar prejudices.

Unlike its historical predecessor, the group was not merely a male organization. The ranks of the Klan in the 1920s also included many women, with chapters of its women’s auxiliary in locations across the country. These women’s groups were active in a number of reform-minded activities, such as advocating for prohibition and the distribution of Bibles at public schools. But they also participated in more expressly Klan activities like burning crosses and the public denunciation of Catholics and Jews. By 1924, this Second Ku Klux Klan had six million members in the South, West, and, particularly, the Midwest. To give a sense of the popularity of the Klan in the 1920s, more Americans were Klansman than there were in the nation’s labor unions at the time. While the organization’s leaders publicly rejected violence, its member continued to employ intimidation, violence, and terrorism against its victims, particularly in the South. The new Ku Klux Klan was a violent organization with a peaceful façade.

The Klan’s newfound popularity proved to be fairly short-lived. Several states effectively combatted the power and influence of the Klan through anti-masking legislation, that is, laws that barred the wearing of masks publicly. As the organization faced a series of public scandals, such as when the Grand Dragon of Indiana was convicted of murdering a White schoolteacher, prominent citizens became less likely to openly express their support for the group without a shield of anonymity. More importantly, influential people and citizen groups explicitly condemned the Klan. Reinhold Niebuhr, a popular Protestant minister and conservative intellectual in Detroit, admonished the group for its ostensibly Protestant zealotry and anti-Catholicism. Jewish organizations, especially the Anti-Defamation League, which had been founded just a couple of years before the reemergence of the Klan, amplified Jewish discontent at being the focus of Klan attention. Moreover, the NAACP, which had actively sought to ban the film The Birth of a Nation, worked to lobby congress and educate the public on lynching, the illegal hanging of African Americans by mobs. Ultimately, however, it was the Great Depression that put an end to the Klan. As dues-paying members dwindled, the Klan lost its organizational power and sunk into irrelevance until the 1950s. Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

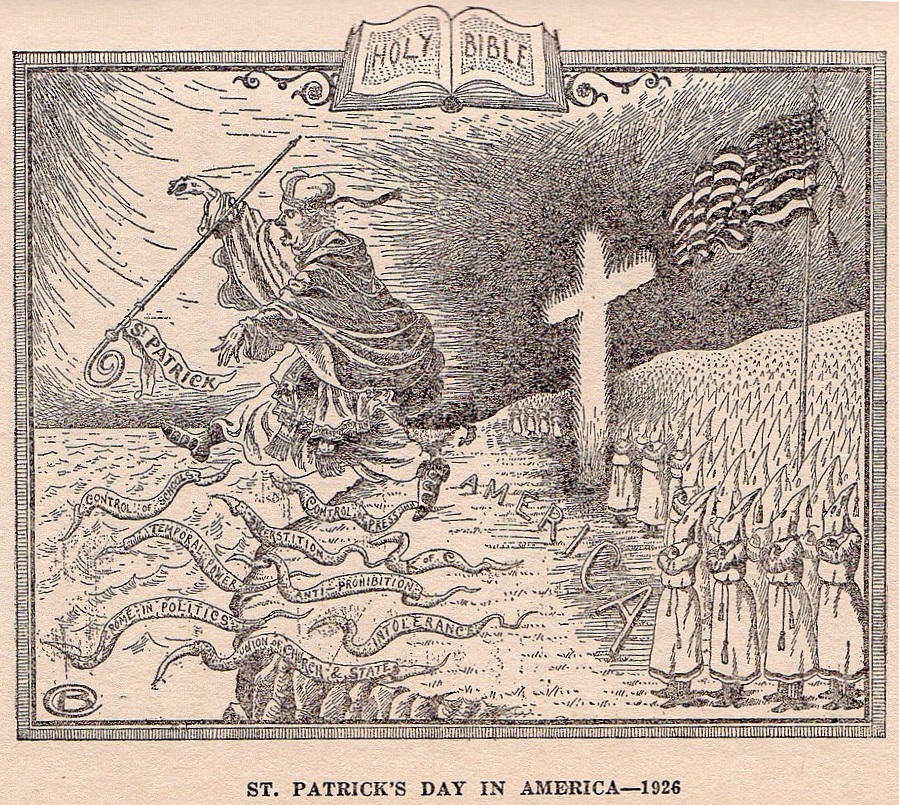

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

A Pro-KKK Cartoon from 1926 depicting the Klan chasing out St. Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland, along with snakes representing the evils the Klan believed immigrant Catholics brought with them. Ironically, many of these evils, including intolerance and control were characteristics of the Klan who, unlike Catholic immigrants, were unwilling to show they faces.

CHRISTIAN FUNDAMENTALISM

The sense of degeneration that the Klan and anxiety over mass immigration prompted in the minds of many Americans was in part a response to the process of postwar urbanization. Cities were swiftly becoming centers of opportunity, but the growth of cities, especially the growth of immigrant populations in those cities, sharpened rural discontent over the perception of rapid cultural change. As more of the population flocked to cities for jobs and quality of life, many left behind in rural areas felt that their way of life was being threatened. To rural Americans, the ways of the city seemed sinful and excessive. Urbanites, for their part, viewed rural Americans as hayseeds who were hopelessly behind the times. Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

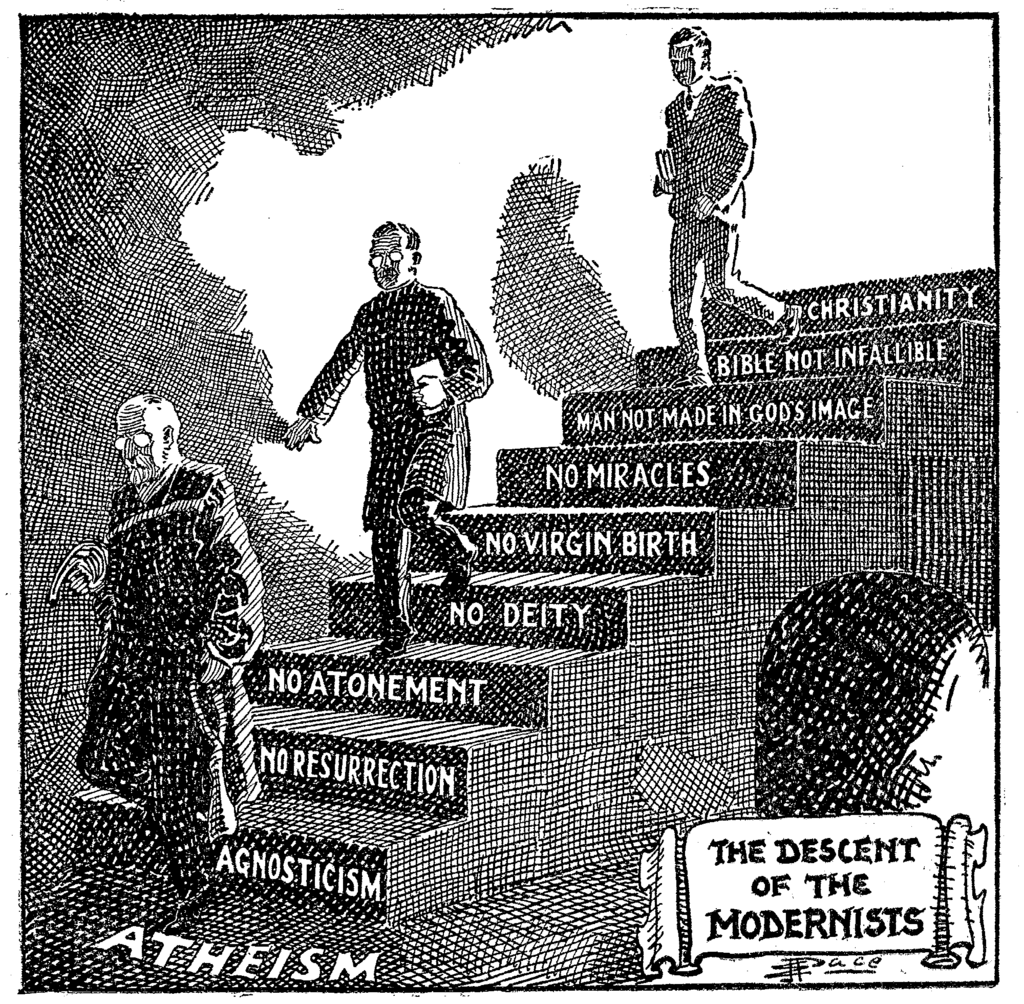

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

This cartoon criticizes the modernists as too willing to bend the moral rules of the Bible, which in the artist’s view, leads eventually to disbelief in god.

The conflict between the modernists of the cities, and the traditionalists of the countryside was best exemplified by the trial of a teacher in Tennessee in 1925.

When Charles Darwin announced his theory that humans and apes had descended from a common ancestor in 1859, he sent shock waves through the Western world. The Theory of Evolution contradicted the Bible’s version of the creation of the world, and churches hotly debated whether to accept the findings of modern science or continue to follow the teachings of ancient scripture. By the 1920s, most of the urban churches of America had been able to reconcile Darwin’s theory with the Bible, but rural preachers preferred to follow a stricter interpretation of the Bible as truth and rejected Darwin’s theory. These religious fundamentalists saw the Bible as the only salvation from a materialistic civilization in decline.

Charles Darwin had first published his theory of natural selection in 1859, and by the 1920s, many standard textbooks contained information about Darwin’s theory of evolution. Fundamentalist Protestants targeted evolution as representative of all that was wrong with urban society. Tennessee’s Butler Act made it illegal “to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.” Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Clarence Darrow, famed defense attorney, came to Dayton to defend John Scopes and the teaching of science. The idea of religious leaders being able to dictate what could and could not be discussed in schools infuriated him.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) believed such laws limited the freedom of speech and led the charge of evolution’s supporters. It offered to fund the legal defense of any Tennessee teacher willing to fight the law in court. The man who accepted the challenge was John Scopes, a science teacher and football coach in Dayton, Tennessee. In the spring of 1925, he walked into his classroom and read, from Hunter’s Civic Biology, part of a chapter on the evolution of humankind and Darwin’s theory of natural selection. His arrest soon followed, and a trial date was set.

Former presidential candidate, populist and fundamentalist champion William Jennings Bryan came to town to argue the case for the prosecution. Bryan had been preaching across the country about the spread of secularism and the declining role of religion in education. He was known for offering $100 to anyone who would admit to being descended from an ape. Clarence Darrow, a prominent lawyer and outspoken agnostic, led the defense team. His statement that, “Scopes isn’t on trial, civilization is on trial. No man’s belief will be safe if they win,” struck a chord with those who feared that fundamentalists were on the verge of dictating what Americans could and could not think.

The trial turned into a media circus. When the case was opened, journalists from across the land descended upon the mountain hamlet of Dayton. H. L. Mencken of The Baltimore Sun provided the trial with its nickname: the Monkey Trial. Preachers and fortune seekers filled the streets. Entrepreneurs sold everything from food to Bibles to stuffed monkeys. It was the first trial to be broadcast on national radio.

The outcome of the trial, in which Scopes was found guilty and fined $100, was never really in question, as Scopes himself had confessed to violating the law. Nevertheless, the trial itself proved to be high drama. The drama only escalated when Darrow made the unusual choice of calling Bryan as an expert witness on the Bible. Knowing of Bryan’s convictions of a literal interpretation of the Bible, Darrow peppered him with a series of questions designed to ridicule such a belief. The result was that those who approved of the teaching of evolution saw Bryan as foolish, whereas many rural Americans considered the cross-examination an insulting attack on the Bible and their faith.

The Scopes Monkey Trial was not the only evidence that fundamentalist Christian belief was on the rise in the 1920s among rural and White Americans. Another example of this shift was the emergence of Billy Sunday as a national icon. As a young man, Sunday had gained fame as a baseball player with exceptional skill and speed. Later, he found even more celebrity as the nation’s most revered evangelist, drawing huge crowds at camp meetings around the country. He was one of the most influential evangelists of the time and had access to some of the wealthiest and most powerful families in the country. Sunday rallied many Americans around fundamentalist religion and garnered support for prohibition. Recognizing Sunday’s popular appeal, Bryan attempted to bring him to Dayton for the Scopes trial, although Sunday politely refused.

Even more spectacular than the rise of Billy Sunday was the popularity of Aimee McPherson, a Canadian Pentecostal preacher whose Foursquare Church in Los Angeles catered to the large community of Midwestern transplants and newcomers to California. Although her message promoted the fundamental truths of the Bible, her style was anything but old fashioned. Dressed in tight-fitting clothes and wearing makeup, she held radio-broadcast services in large venues that resembled concert halls and staged spectacular faith-healing performances. Blending Hollywood style and modern technology with a message of fundamentalist Christianity, McPherson exemplified the contradictions of the decade well before public revelations about a scandalous love affair cost her much of her status and following. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

The Angelus Temple in the Echo Park neighborhood of Los Angeles was the center of Aimee Semple McPherson’s Foursquare Church. It is still in operation today.

PROHIBITION

After many decades of hard work, the Temperance Movement finally succeeded in banning alcohol in the United States when, on October 28, 1919, the 18th Amendment to the Constitution was implemented through the Volstead Act, which went into effect on January 17, 1920. A total of 1,520 Prohibition agents from three separate federal agencies, the Coast Guard, the Treasury Department’s Internal Revenue Service Bureau of Prohibition, and the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Prohibition, were tasked with enforcing the new law.

The effort to enforce the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act was always problematic. Outlawing drugs, especially a drug like alcohol that has a long history of use, is a challenging mix of law enforcement and changing public opinion. With the job of enforcing the law separated between different departments, it was hard to know who was in charge in what areas, and who was responsible for what tasks. Geography presented another complication. America is a vast nation with many places to hide illegal brewing and distilling operations. To make matters worse, Canada and Mexico did not ban alcohol and the extensive seaways, ports, and massive borders running along Canada and Mexico, made it exceedingly difficult to stop bootleggers intent on bringing alcohol into the country.

While the commercial manufacture, sale, and transport of alcohol was illegal, Section 29 of the Volstead Act allowed private citizens to make wine and cider from fruit, but not beer, in their homes. Up to 200 gallons per year could be produced, with some vineyards growing grapes for purported home use. In addition to this loophole, the wording of the act did not specifically prohibit the consumption of alcohol. In anticipation of the ban, many people stockpiled wines and liquors during the latter part of 1919 before alcohol sales became illegal in January 1920. As Prohibition continued, people began to perceive it as illustrative of class distinctions, since it unfairly favored social elites who could afford to purchase in bulk. Working-class people were enraged that their employers could dip into a cache of private stock while they were unable to afford similar indulgences. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Deputies dump illegal alcohol during the 1920s.

CRIME

The rift between the Dries, who favored prohibition, and the Wets who wanted to legalize alcohol consumption and sales again, hinged on the long-running debate over whether drinking was morally acceptable in light of the antisocial behavior that overindulgence could cause. Ironically, this dispute over ethics during the era of prohibition led to a sudden groundswell of criminal activity, with those who opposed legal alcohol sales unintentionally enabling the growth of vast criminal organizations that controlled the illegal sale and distribution of alcohol and related activities including gambling and prostitution.

Powerful gangs corrupted law enforcement agencies, leading to the blanket criminal activity of racketeering, which includes bribery, extortion, loan sharking, and money laundering. Illicit alcoholic beverage industries earned an average of $3 billion per year in illegal income, none of which was taxed, and effectively transformed cities into battlegrounds between opposing bootlegging gangs.

Chicago, the largest city in the Midwest and of one America’s true metropolises along with New York and Los Angeles, became a haven for Prohibition dodgers. Many of Chicago’s most notorious gangsters, including Al Capone and his archenemy, Bugs Moran, made millions of dollars through illegal alcohol sales. By the end of the decade, Capone controlled all 10,000 Chicago speakeasies, illegal nightclubs where alcohol was sold, and ruled the bootlegging business from Canada to Florida. Numerous other crimes, including theft and murder, were directly linked to criminal activity in Chicago and other cities.

THE EFFECTS OF PROHIBITION

Prohibition had a large effect on music in the United States, specifically on jazz. Speakeasies became far more popular during the Prohibition era than bars had been, partially influencing the mass migration of jazz musicians from New Orleans to major northern cities such as Chicago and New York. This movement led to a wider dispersal of jazz, as different styles developed in different cities. In this way, prohibition may have also helped pave the way for limited integration, as it united mostly African American musicians with mostly White crowds.

Prohibition also had an effect on gender rules. As the saloon began to die out, public drinking lost much of its macho association, resulting in an increased social acceptance of women drinking in the semipublic environment of a speakeasy. This new norm established women as a notable new target demographic for alcohol marketers, who sought to expand their clientele.

By the 1930s, the Great Depression had settled over the country. Millions of Americans were out of work and times were hard. Americans were ready for a drink. On December 5, 1933, ratification of the 21st Amendment repealed the 18th Amendment. As Prohibition ended, some of its supporters, including industrialist and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, openly admitted its failure.

In a positive epilogue, however, the overall consumption of alcohol dropped and remained below pre-Prohibition levels. In the end, the Temperance Movement succeeded in reducing, if not eliminating, the drinking of alcohol in America.

CONCLUSION

Clearly prohibition failed. Americans simply did not want to be told they could not drink alcohol. Despite efforts to enforce the 18th Amendment, drinking did not stop. In fact, prohibition of alcohol did not lead Americans to give up alcohol, it made us drinkers who also had to endure increased crime.

In the case of the Butler Act, fundamentalists were unable to legislate what Americans could and could not think about the origin of the human species, and in the case of the KKK, they failed to turn the entire nation against immigrants, Jews, Catholics and African Americans, although they certainly turned the minds of many.

All of this work to make people think or behave in certain ways worked partially, but not fully. On the other hand, some laws such as those that prohibit violent crime, are still with us today and seem to be doing a pretty good job of keeping people from behaving violently.

What do you think? Can laws make us moral?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The 1920s was a time when there were major conflicts between Americans about what was right and wrong.

Fueled partly by the popularity of a movie celebrating the Ku Klux Klan in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, the KKK became popular and quite common in the 1920s. They targeted their hatred on African Americans, immigrants, Catholics and Jews. Although the Klan’s leaders promised to be non-violent, in reality the members of the Klan carried out numerous lynching and other forms of terrorism.

The 1920s saw the rise of Christian Fundamentalism who reacted to new inventions and excitement about science by teaching that truth can be found in the Bible. Most importantly, they focused on preventing Darwin’s Theory of Evolution from being taught in public schools because it conflicted with the Biblical story of creation.

Although some Americans wanted their children to learn the Bible’s version of creation in public school, others did not like it that Christian teachings were being enacted into law. In 1925, a great court case showed off the conflict between these modernists and traditionalists. In Tennessee, the Butler Act had made it illegal to teach any version of creation other than the story found in the Bible. When John Scopes taught Darwin’s theory he was arrested.

Great lawyers came to try the case, and although Scopes lost (it was obvious he had broken the law), the nation watched with great interest as the Bible itself seemed to be on trial.

Other leaders tapped into a growing interest in traditional religion. Billy Sunday and Aimee Semple McPhereson both built large followings as they toured the nation speaking to large audiences.

The 1920s are also remembered as the era of Prohibition. Beginning in 1919, alcohol was illegal in the United States. Preventing people from making, selling, buying and drinking alcohol was incredibly difficult. Although Prohibition was supposed to reduce crime, crime actually became more common as gangs fought each other over control of the making and distribution of illegal alcohol. Most famous of these was Al Capone’s gang in Chicago. Police forces, who were supposed to enforce the laws, often were paid by bar owners to look the other way, or simply ignored the law since they wanted to drink also. Finally, after 14 years, the 21st Amendment made alcohol legal again.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Ku Klux Klan (KKK): Racist organization based in the South that terrorized African Americans after the Civil War and helped establish the system of Jim Crow. They were also anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic and anti-Semitic. The organization experienced a revival in the 1920s and again during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s.

Anti-Defamation League: Jewish organization that works against anti-Semitism.

Modernists: People who embrace science and changes as positive influences on society. In the 1920s they were concentrated in cities.

Traditionalists: People who rejected changes and embraced traditional values, especially Christianity instead of science. In the 1920s they were concentrated in rural areas and the South.

Charles Darwin: British naturalist who proposed the Theory of Evolution and wrote the book “On the Origin of Species.”

Fundamentalists: People who embraced the Bible and traditional Christian teachings and rejected scientific theories that contradict the Bible. Rural areas and the Bible Belt in the South are the heart of this thinking.

American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU): Organization that provides lawyers to defend people they believe have had their basic rights violated. For example, they defend freedom of speech cases and in the 1920s, helped defend John Scopes.

John Scopes: High school biology teacher in Tennessee who was accused of violating the Butler Act. His trial became a symbol of the conflict between modernists and traditionalists during the 1920s.

William Jennings Bryan: Former populist and democratic presidential candidate who became the primary champion of traditionalist and fundamentalists in the 1920s. He promoted laws such as the Butler Act and led the prosecution at the Scopes Trial.

Clarence Darrow: Famous attorney in the 1920s who rejected traditionalism as an encroachment on individual freedom of belief and led the defense of John Scopes.

Billy Sunday: Former baseball star and widely followed evangelist preacher during the 1920s. He promoted fundamentalism and prohibition.

Aimee Semple McPherson: Preacher from Los Angeles during the 1920s who helped promote fundamentalism. She was famous for broadcasting her services on the radio and wearing fashionable cloths while preaching, as well as series of scandalous love affairs.

Bootleggers: People who imported illegal alcohol during prohibition.

Dries: People who supported prohibition.

Wets: People who opposed prohibition.

Al Capone: Nicknamed “Scarface,” he was the most famous gangster during the era of prohibition. He ran the illegal alcohol operation in Chicago and although was renowned for violence, eventually went to jail for tax evasion.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Lynching: Illegal hanging by a mob. It is a term most commonly used when White mobs hung African American men and was common throughout the South during the Jim Crow era.

Theory of Evolution: Theory proposed by Charles Darwin that all life is the result of evolution. Teaching this theory was outlawed in Tennessee by the Butler Act.

![]()

COURT CASES

Scopes “Monkey” Trial: Trial of biology teacher John Scopes in 1925 that became a visible symbol of the conflict between modernists and traditionalists.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Speakeasy: A bar where illegal alcohol was sold during prohibition.

![]()

MOVIES

The Birth of a Nation: 1915 movie by D. W. Griffith that glorified the history of the KKK in the years after the Civil War. It helped revive the KKK during the 1920s.

![]()

LAWS

Butler Act: Law passed in the 1920s in Tennessee that banned the teaching of Darwin’s Theory of Evolution. John Scopes was charged with violating this law.

18th Amendment: Amendment to the constitution that outlawed alcohol and established prohibition.

Volstead Act: 1919 law that implemented the 18th Amendment and made alcohol illegal, thus initiation prohibition.

21st Amendment: Amendment to the Constitution ratified in 1933 that ended prohibition by repealing the 18th Amendment.