JUMP TO

TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

In 1898, the United States fought a war with Spain. It was a “splendid little war” as one politician called it. Few Americans died. The army and navy proved themselves in battle and America won significant territory. In short, it was a smashing success.

Afterward, the United States found itself engaged in a long, ugly, bloody war to try to impose its authority in the Philippines over a determined Filipino independence movement.

While the Spanish-American War was an unqualified victory, the Philippine-American War proved to be a cautionary tale of the challenges of empire building.

Did the United States deserve the spoils of its victory over the Spanish? Did we deserve the trouble we had in the Philippines?

In short, did we deserve the outcomes of these two wars?

CUBA

America’s relationship with Cuba long predated the Imperialist Era. Even before the Civil War, southern planters had considered annexing Cuba as a way of adding another slave state to the Union. In the end, this scheme failed, and Cuba remained a Spanish colony, but the island so close to Florida remained a particular interest of many Americans.

Cubans were not particularly excited about the idea of being annexed by the United States, but by the late 1800s, they were certainly not interested in remaining a part of the Spanish empire. Most other nations in Central and South America had long before become independent.

Revolts against Spanish rule were becoming common. With the abolition of slavery in 1886, former slaves joined the ranks of farmers and the urban working class in agitating for change. Many wealthy Cubans lost their property, and the number of sugar mills declined. Only companies and the most powerful plantation owners remained in business, and during this period, American money began flowing into the country as American investors bought up struggling plantations. Although it remained Spanish territory politically, Cuba started to depend on the United States economically.

In 1881, the Cuban revolutionary leader José Martí moved to the United States to escape Spanish authorities. There he mobilized the support of the Cuban exile community, especially in southern Florida. He aimed for a revolution and independence from Spain, but also lobbied against American annexation of Cuba, which some American and Cuban politicians desired.

For a variety of reasons, Americans sympathized with the Cuban rebels in their struggle for independence. The United States had gone through a similar struggle with Great Britain a century earlier. The revolutionists also carried out an effective propaganda campaign, which included destruction of American sugar mills and railroads, designed to bring about American intervention in the revolt. The Cuban rebels strategized, not unreasonably, that if America became involved in dispute, it would likely be on the side of the Cubans seeking independence. The propaganda campaign was carried on in New York City under the guidance of rebel leader José Martí.

Spain did not have any intention to grant Cuban independence and in 1895, the Spanish government dispatched 50,000 troops to the island. Things did not go well, and with their efforts to suppress the rebellion going badly, in 1896 Spain sent General Valeriano Weyler to Cuba. Weyler established concentration camps to hold captured rebels in addition to other hard-nosed policies. During the presidential election of that year in the United States, the Republican Party had adopted an expansionist platform, which helped get William McKinley elected. The existence of the Weyler policy of reconcentrado, which led to his being known as “Butcher Weyler,” kept interest in the Cuban affair at a high level. Americans began demonstrating in order to display their opposition to Spanish rule in Cuba.

As Congress called for recognition of the rights of the rebelling Cubans, President McKinley offered to mediate with Spain for Cuban independence. Spain declined, but otherwise did its best to satisfy American concerns, not wishing war with an emerging world power. Meanwhile, the two American ambassadors involved, seemed to be working in opposite directions. While Ambassador Stewart L. Woodford was trying to pursue a peaceful resolution with Spain in Madrid, Ambassador Fitzhugh Lee in Havana seemed to be stirring things further in the opposite direction. Primary Source: Drawing

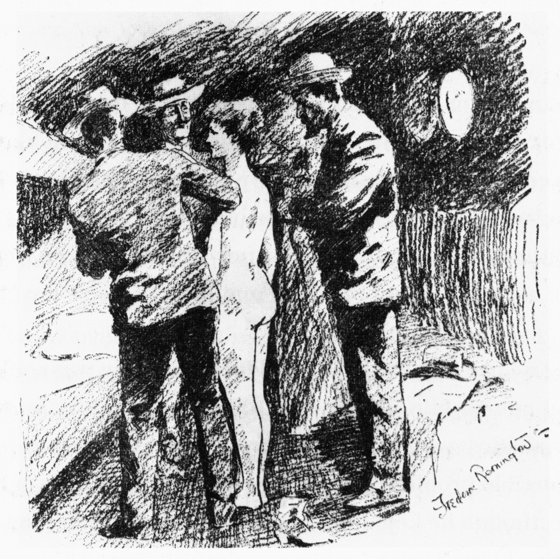

Primary Source: Drawing

The provocative, and entirely fictitious, strip searching of American women by Spanish authorities that was reported in William Randolph Hurst’s newspapers. Stories like these inflamed public opinion and pushed President McKinley to ask for a declaration of war.

REMEMBER THE MAINE

Yellow journalism made itself felt during the Cuban conflict. William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer vied for readership in a circulation war using tactics of exaggeration and sensationalism to keep readers buying their papers. One myth of the war says that when Hearst dispatched a photographer to Cuba to take pictures of the war, his man telegraphed back that there was not any war to photograph. Hearst is said to have responded, “You take care of the pictures. I’ll take care of the war!” Hearst published a sensational drawing on the front page of his Journal of an American woman being strip-searched by Spanish officers. The story was false, but it sold newspapers. Historian Page Smith has called the press behavior in the Cuban matter “disgraceful,” an opinion widely shared today.

Still attempting to avoid war, Spain replaced General Weyler with General Blanco and began to reform its policy in Cuba in an attempt to meet America’s growing demands. With various interests in Spain, Cuba, and the United States all pulling in different directions, however, President McKinley was at something of a loss to find the most reasonable course. Just when it looked as though a peaceful settlement might be reached, two unfortunate events occurred. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

The USS Maine sailing into Havana Harbor.

American Consul in Havana, Fitzhugh Lee, the son of Confederate general Robert E. Lee, requested a show of naval force to calm things down, and the USS Maine was sent to Havana harbor, clearly a provocative act.

While the Maine lay at anchor in Havana, a letter written by Spanish ambassador De Lome in Washington insulting President McKinley was stolen from the mail by a Cuban revolutionary. He turned it over to a reporter of the Hearst newspapers, which Hearst published in the New York Journal. Americans were outraged, and De Lome was forced to resign.

One week later the Maine, which had been sent “as a friendly act of courtesy” to protect American lives and property, blew up, killing over 200 American sailors. Of all those least likely to be responsible, Spain headed the list. Nevertheless, the yellow press adopted the slogan “Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain!” Much later it was determined that the explosion aboard the Maine was probably an accident, but the damage to international relationships had been done.

The Spanish ambassador was not the only one who thought President McKinley was wishy-washy. Although it is clear that he wanted Spain out of Cuba, even going so far as to offer to purchase the island, he was not hell-bent on going to war. Historians have generally concluded, however, that the American public, aroused by the yellow press, pushed the president into seeking a declaration of war. Reluctantly President McKinley, himself a veteran of the horrors of the Civil War, asked Congress to declare war on Spain and on April 25, 1898, the United States officially entered a state war with Spain. An amendment known as the Teller Amendment was added to the declaration, indicating that the United States had no intention to annex Cuba. Secondary Source: Painting

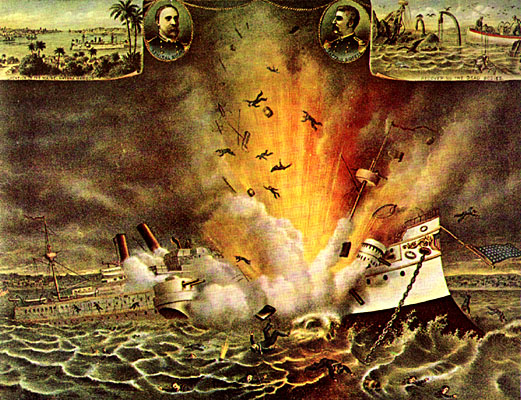

Secondary Source: Painting

No photographs of the actual explosion of the Maine exist. This is one artist’s depiction of the event which certainly captures the nation’s horror.

THE SPLENDID LITTLE WAR

The Splendid Little War, as with was later called by Secretary of State John Hay, was handily won by the United States over an inept Spanish army and navy. Americans supported the war enthusiastically, and many young men volunteered. However, the regular army, which had done little but fight Native Americans since the Civil War, was ill prepared to manage the mobilization necessary to get on a war footing and mobilization was slow, clumsy and it was months before any American soldiers actually landed on Cuba.

The navy, on the other hand, was in good trim, having been expanded during the previous decades in response to the writings of Mahan and the support of other navalists like Theodore Roosevelt. The navy fought well from the beginning. Commodore George Dewey, dispatched from Hong Kong, destroyed the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay in the Philippines, suffering only minor casualties to his ships and men. Later Admirals Sampson and Schley defeated the Spanish fleet off the coast of Cuba. The movement of naval vessels between Asia and the United States and around the tip of South America underscored the need for a canal between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans in Central America.

Although the Army was plagued by inefficiency, disease and disorder, American ground forces were bolstered by volunteers such as Theodore Roosevelt’s famous Rough Riders. American soldiers fought bravely enough to defeat a hapless Spanish army near Santiago. American troops also occupied Puerto Rico, another Caribbean island Spanish colony. The fighting, which lasted less than four months, saw fewer than 400 American soldiers killed in combat. Over ten times as many died from disease, however.

The most popular image of the Spanish-American War is of Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Riders, charging up San Juan Hill. But less well known is that the Rough Riders struggled mightily in several battles and would have sustained far more serious casualties, if not for the experienced black veterans, over 2,500 of them, who joined them in battle. These soldiers, who had been fighting the Indian Wars on the American frontier for many years, were instrumental in the victory in Cuba. Primary Source: Photograph

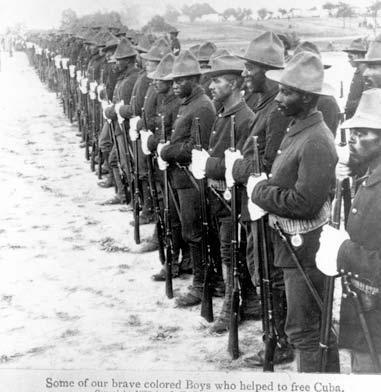

Primary Source: Photograph

Some of the African American troops who fought in Cuba. Many of them were veterans of the Indian Wars in the West where they had been called Buffalo Soldiers by the Native Americans. In Cuba, they were given the nickname Smoked Yankees.

The choice to serve in the Spanish-American War was not a simple one. Within the African American community, many spoke out both for and against involvement in the war. Some felt that because they were not offered the true rights of citizenship it was not their burden to volunteer for war. Others, in contrast, argued that participation in the war offered an opportunity for African Americans to prove themselves to the rest of the country. While their presence was welcomed by the military which desperately needed experienced soldiers, the Black regiments suffered racism and harsh treatment while training in the southern states before shipping off to battle.

Once in Cuba, however, the Smoked Yankees, as the Cubans called the African American soldiers, fought side-by-side with Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, providing crucial tactical support to some of the most important battles of the war. After the Battle of San Juan, five African American soldiers received the Medal of Honor and 25 others were awarded a certificate of merit. One reporter wrote that “if it had not been for the Negro cavalry, the Rough Riders would have been exterminated.” For some of the soldiers, their recognition made the sacrifice worthwhile. Others, however, struggled with American oppression of Cubans and Puerto Ricans, feeling kinship with the black residents of these countries who fell under American rule.

THE PHILIPPINE-AMERICAN WAR

As the war closed, Spanish and American diplomats arranged for a peace conference in Paris. They met in October 1898, with the Spanish government committed to regaining control of the Philippines, which they felt were unjustly taken in a war that was solely about Cuban independence. President McKinley was reluctant to relinquish the strategically useful prize of the Philippines. He certainly did not want to give the islands back to Spain, nor did he want another European power to step in to seize them. Neither the Spanish nor the Americans considered giving the islands their independence, since, with the pervasive racism and cultural stereotyping of the day, they believed the Filipino people were not capable of governing themselves. William Howard Taft, the first American governor-general to oversee the administration of the new American possession, accurately captured American sentiments with his frequent reference to Filipinos as “our little brown brothers.”

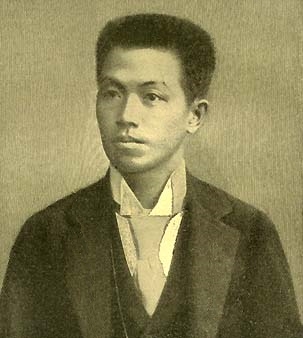

Philippine revolutionary Emilio Aguinaldo refused to exchange Spanish occupation for American and continued the insurrection he had been leading against the Spanish with a fight against the new American invaders. The result was the Philippine-American War, or the Filipino Insurrection. It was one of the ugliest wars in American history.

The Filipinos’ war for independence lasted three years, with over 4,000 American and 20,000 Filipino combatant deaths. The civilian death toll is estimated to be as high as 250,000. Under the rule of the American military, the Philippines remained a war zone with terrible atrocities committed by American troops against Filipino soldiers and civilians alike. Frustrated with a lack of progress, President McKinley turned the Philippines over to a civilian governor. Under Taft’s leadership, Americans built a new transportation infrastructure, hospitals, and schools, hoping to win over the local population. The rebels lost influence, and Aguinaldo was captured by American forces and forced to swear allegiance to the United States. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

This photograph of Emilio Aguinaldo was taken in 1898 at the start of the Spanish-American War. As he grew older he continued to play a vital role in the development of his country.

Taft continued to introduce reforms to modernize and improve daily life for the country despite pockets of resistance that continued to fight through the spring of 1902. Much of the commission’s rule centered on legislative reforms to local government structure and national agencies, with the commission offering appointments to resistance leaders in exchange for their support.

The war officially ended on July 2, 1902, with a victory for the United States. However, some Philippine groups led by veterans of the Katipunan continued to battle American forces. Among those leaders was General Macario Sakay, a veteran Katipunan member who assumed the presidency of the proclaimed Tagalog Republic, formed in 1902 after the capture of President Emilio Aguinaldo. Other groups, including the Moro people and Pulahanes people, continued hostilities in remote areas and islands until their final defeat a decade later at the Battle of Bud Bagsak on June 15, 1913.

The occupation by the United States changed the cultural landscape of the islands. English became the primary language of government, education, business, and industry, and increasingly in future decades, of families and educated individuals. The Catholic Church lost its place as the official state religion, although most Filipinos remain Catholic to this day. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Katipunenos, Filipinos who continued the fight against the Americans even after Aguinaldo was captured.

In 1916, Congress passed the Philippine Autonomy Act, Jones Act, that the United States officially promised eventual independence, along with more Philippine control in the meantime over the Philippines. The 1934 Philippine Independence Act created in the following year the Commonwealth of the Philippines, a limited form of independence, and established a process ending in Philippine independence, which was originally scheduled for 1944, but interrupted and delayed by World War II. Finally in 1946, following World War II and the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, the United States granted independence through the Treaty of Manila.

OPPOSITION

Some Americans, notably William Jennings Bryan, Mark Twain, Andrew Carnegie, Ernest Crosby, and other members of the American Anti-Imperialist League, strongly objected to the annexation of the Philippines. Anti-imperialist movements claimed that the United States had become a colonial power by replacing Spain as master of the Philippines. Other anti-imperialists opposed annexation on racist grounds. Among these was Senator Benjamin Tillman of South Carolina, who feared that annexation of the Philippines would lead to an influx of non-White immigrants into the United States. As news of atrocities committed in subduing the Philippines arrived in the United States, support for the war flagged. President McKinley and Governor Taft’s efforts to end the conflict by exchanging peace for partial self-rule was, in part, due to a loss of public support.

LEGACY OF THE WARS

The result of the Spanish-American War was the 1898 Treaty of Paris, negotiated on terms favorable to the United States. The United States gained several island possessions. Spain turned over Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the United States, for which the United States paid Spain $20 million. Puerto Rico and Guam remain American territories and the people of those territories are US citizens, although since they are not states, they have no representation in Congress and no vote for president.

The wars marked America’s entry into world affairs. Before the Spanish-American War, the United States was characterized by isolationism, an approach to foreign policy that emphasized keeping the affairs of other countries at a distance. Although Americans still disagree about the extent we should play in world affairs, since the Spanish-American War, the United States has had a significant hand in various conflicts around the world, and has entered many treaties and agreements.

After the Spanish-American War, the United States entered a long and prosperous period of economic and population growth and technological innovation that lasted through the 1920s. The war redefined national identity, served as a solution of sorts to the social divisions plaguing the American mind, and provided a model for future news reporting.

The war also effectively ended the Spanish Empire. Spain had been declining as an imperial power since the early 1800s. Spain retained only a handful of overseas holdings: Spanish West Africa, Spanish Guinea, Spanish Sahara, Spanish Morocco, and the Canary Islands. Never again would Spain be a major player on the world stage.

The United States continued to occupy Cuba at the end of the war. As in the Philippines, reforms were initiated in public administration, and public health agencies were brought under the direction of General Leonard Wood. American doctors Walter Reed and William Gorgas exterminated yellow fever in Cuba and pushed education and other reforms. A constitutional convention called in 1900 set up a Cuban government, and Americans withdrew in 1902.

However, Cuban independence was not without limits. Congress pass the Platt Amendment of 1903 which added these stipulations. First, Cuba could make no treaties with other nations without America’s consent. The Cuban government could not go into debt beyond its ability to pay. The United States reserved the right to intervene in Cuba to maintain law and order. And, the United States was granted rights to a naval base at Guantanamo Bay. Despite the antagonistic relationship the United States has with the Cuban government today, the base at Guantanamo Bay remains in American hands. Because it is not on American soil, it has served as a legally ambiguous place to detain permanently accused terrorists captured in Afghanistan.

CONCLUSION

The Spanish-American War gave the United States new territory, national pride, and launched the nation into first class status among the leaders of the world. While the reasons for declaring war might have been dubious, the cause of Cuban independence was noble and achieved. The spoils of war – territory won – was seemingly earned.

In the Philippines, the spoils of war were less lustrous. Those who oppose imperialism might see the horrors of the Filipino Insurrection as a just punishment for hubris.

What do you think? Did the United States deserve the outcomes of these two wars?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The United States fought a war with Spain that was about Cuban independence, but led to the acquisition of former Spanish territories such as Puerto Rico and the Philippines.

The United States went to war with Spain in 1898 because of Cuba. Cuba was one of the last Spanish colonies in the Americas. Cubans wanted independence, and some people in the United States were sympathetic to the Cuban cause.

At the time, newspapers were competing with each other to sell more copies. Writers and publishers exaggerated stories and used bold, sensational headlines. A popular topic was Spanish cruelty toward Cubans. After reading such stories, many Americans wanted the United States to intervene in Cuba.

The USS Maine, an American battleship, exploded while visiting Havana, Cuba. It is still unclear why the explosion happened, but Americans blamed the Spanish and demanded war.

As part of the declaration of war, Congress passed a law stating that it would not make Cuba an American colony.

The Spanish-American War was a lopsided victory for the United States. American ships destroyed the Spanish fleet in the Philippines and American troops overran the Spanish troops in Cuba. Theodore Roosevelt became a national hero while leading his men in battle in Cuba.

True to their promise, the United States allowed Cuba to become independent, but passed a law saying that they would intervene if there were problems in Cuba. In this way, Cuba was always mostly, but not entirely independent.

As a result of the war, the United States took control of the Spanish territories of Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines.

The Filipinos had also been fighting for independence when the war broke out. Filipino leaders thought that the war would lead to independence the same that it had for Cuba. However, after defeating the Spanish, the Americans stayed. The Filipino freedom fighters began a rebellion against American rule. A bloody conflict resulted.

In the end, Americans captured Emilio Aguinaldo, the leader of the Filipino resistance and the rebellion ended. The Filipinos agreed to a deal in which the Americans maintained control of the country but allowed the Filipinos to make many of their own decisions. The United States kept the Philippines as a colony for about 50 years.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

José Martí: Cuban poet and leader of the Cuban independence movement.

George Dewey: American naval commander at the Battle of Manila Bay during the Spanish-American War.

Rough Riders: Nickname for Theodore Roosevelt’s cavalry regiment in Cuba during the Spanish-American War.

Smoked Yankees: Nickname for African-American troops during the Spanish-American War.

William Howard Taft: American governor of the Philippines after the Spanish-American War and later president of the United States.

Emilio Aguinaldo: Leader of the Philippine independence movement who fought both the Spanish and the United States.

Mark Twain: American author of such books as Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn and famous anti-imperialist.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Remember the Maine: Rallying cry during the Spanish-American War.

Splendid Little War: Nickname for the Spanish-American War.

![]()

SHIPS

USS Maine: American battleship that exploded mysteriously in Havana Harbor. The explosion was the catalyst for the Spanish-American War.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Cuba: Island nation just south of Florida that was a Spanish colony until the United States secured its independence in the Spanish-American War.

Havana: Capital city of Cuba.

Puerto Rico: Island in the Caribbean won by the United States from Spain in the Spanish-American War. It remains an American territory.

Guam: Island in Micronesia won by the United States from Spain in the Spanish-American War. It remains an American territory.

Philippines: Island nation in Asia won by the United States from Spain in the Spanish-American War. It was granted independence in 1946.

![]()

EVENTS

Explosion of the USS Maine: Event that cause the United States to declare war on Spain in 1898.

Spanish-American War: 1898 conflict with Spain in which the United States won control of Puerto Rico, Guam, the Philippines, and also won independence for Cuba.

Battle of Manila Bay: Naval encounter between American and Spanish ships in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War. It was a total victory for the United States.

Philippine-American War: Conflict between the American army and Philippine independence fighters after the Spanish-American War.

![]()

TREATIES & LAWS

Teller Amendment: Amendment to the declaration of war against Spain in 1898 that state that the United States would not annex Cuba.

Jones Act: 1916 law that promised independence for the Philippines

Treaty of Manila: Treaty that officially granted the Philippines independence in 1946.

Treaty of Paris of 1898: Treaty that ended the Spanish-American War and granted the United States control of Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines.

Platt Amendment: Law passed in 1903 in which the United States claimed the right to intervene in Cuban affairs, to maintain a naval base at Guantanamo, and limited the freedom of Cuba to make treaties without American consent.