JUMP TO

TRANSLATE

INTRODUCTION

As you probably have already come to understand, the Gilded Age was a time of extremes. On one hand, there were some Americans who through their ingenuity and determination, and probably a fair amount of luck, became fabulously rich. On the other hand, there were so many more who struggled everyday to earn enough to feed their families. Americans were farmers, but were quickly becoming city dwellers.

Amid all this change, reformers worked to improve the lives of those around them. Like the muckrakers, or the Progressive Presidents, many everyday Americans worked in thousands of small ways to make America a better place.

Some worked to improve the lives of farmers, or laborers, or children, or immigrants. Some wanted political change. Others just wanted to help fellow citizens find a job.

The people who worked to make that change were known as the Progressives. What do you think? What does it mean to be progressive?

THE POPULISTS

Like the oppressed laboring classes of the East, it was only a matter of time before Western farmers would attempt to use their numbers to effect positive change. In 1867, the first such national organization was formed. Led by Oliver Kelley, the Patrons of Husbandry, also known as the Grange, organized to address the social isolation of farm life. Like other secret societies, such as the Masons, Grangers had local chapters with secret passwords and rituals.

The local Grange sponsored dances and gatherings to attack the doldrums of daily life. It was only natural that politics and economics were discussed in these settings, and the Grangers soon realized that their individual problems were common.

Identifying the railroads as the chief villains, Grangers lobbied state legislatures for regulation of the industry. By 1874, several states passed the Granger laws, establishing maximum shipping rates. Grangers also pooled their resources to buy grain elevators of their own so that members could enjoy a break on grain storage.

Farmers’ alliances went a step further. Beginning in 1889, Northern and Southern Farmers’ Alliances championed the same issues as the Grangers, but also entered the political arena. Members of these alliances won seats in state legislatures across the Great Plains to strengthen the agrarian voice in politics.

What did all the farmers seem to have in common? The answer was simple: debt. Looking for solutions to this condition, farmers began to attack the nation’s monetary system. As of 1873, Congress declared that all federal money must be backed by gold. This limited the nation’s money supply and benefited the wealthy.

The farmers wanted to create inflation. Inflation actually helps debtors. The economics are simple. If a farmer owes $3,000 and can earn $1 for every bushel of wheat sold at harvest, he needs to sell 3,000 bushels to pay off the debt. If inflation could push the price of a bushel of wheat up to $3, he needs to sell only 1,000 bushels. Of course, inflation is bad for the bankers who made the loans.

To create inflation, farmers suggested that the money supply be expanded to include dollars not backed by gold. First, farmers attempted to encourage Congress to print Greenback Dollars like the ones issued during the Civil War. Since the greenbacks were not backed by gold, more dollars could be printed, creating an inflationary effect.

The Greenback Party and the Greenback-Labor Party each ran candidates for President in 1876, 1880, and 1884 under this platform. No candidate was able to muster national support for the idea, and farmers turned to another strategy.

Inflation could also be created by printing money that was backed by silver as well as gold. This idea was more popular because people were more confident in their money if they knew it was backed by a precious metal. Also, America had coined money backed by silver until 1873.

Out of the ashes of the Greenback-Labor Party grew the Populist Party. In addition to demanding the free coinage of silver, the Populists called for a host of other reforms. They demanded a graduated income tax, whereby individuals earning a higher income paid a higher percentage in taxes.

They wanted Constitutional reforms as well. Up until this point, Senators were still not elected by the people directly. They were chosen by state legislatures. The Populists demanded a constitutional amendment allowing for the direct election of Senators.

They demanded democratic reforms such as the initiative, where citizens could directly introduce debate on a topic in the legislatures. The referendum would allow citizens, rather than their representatives, to vote a proposed law. Recall would allow the people to end an elected official’s term before it expired. They also called for the secret ballot and a one-term limit for the president.

In 1892, the Populists ran James Weaver for president on this ambitious platform. He poled over a million popular votes and 22 electoral votes. Although he came far short of victory, Populist ideas gained traction at the national level. When the financial Panic of 1893 hit the following year, an increased number of unemployed and dispossessed Americans gave momentum to the Populist movement. A great showdown was in place for 1896.

THE ELECTION OF 1896

All the elements for political success seemed to be falling into place for the Populists. James Weaver made an impressive showing in 1892, and Populist ideas were being discussed across the nation. The Panic of 1893 was the worst financial crisis to date in American history. As the soup lines grew larger, so did voters’ anger.

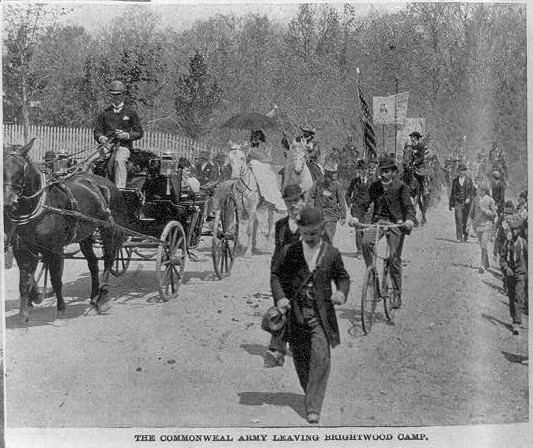

When Jacob S. Coxey of Ohio marched his 200 supporters, dubbed Coxey’s Army, into the nation’s capital to demand reforms in the spring of 1894, many thought a revolution was brewing. The climate seemed to ache for change. All that the Populists needed was a winning Presidential candidate in 1896. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Coxey’s Army in Washington, DC

Ironically, the person who defended the Populist platform that year came from the Democratic Party. William Jennings Bryan was the unlikely candidate. An attorney from Lincoln, Nebraska, Bryan’s speaking skills were among the best of his generation. Known as the “Great Commoner,” Bryan developed a reputation as defender of the farmer. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

William Jennings Bryan speaking during the Election of 1896. He was known as a dynamic speaker.

When Populist ideas began to spread, Democratic voters of the South and West gave enthusiastic endorsement. At the Chicago Democratic convention in 1896, Bryan delivered a speech that made his career. Demanding the free coinage of silver, Bryan shouted, “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold!” Thousands of delegates roared their approval, and at the age of thirty-six, the “Boy Orator” received the Democratic nomination.

Faced with a difficult choice between surrendering their identity and hurting their own cause, the Populist Party nominated Bryan as their candidate as well, effectively merging the Populist and Democratic Parties.

The Republican competitor was William McKinley, the governor of Ohio. He had the support of the moneyed eastern establishment. Behind the scenes, a wealthy Cleveland industrialist named Marc Hanna was determined to see McKinley elected. He, like many of his class, believed that the free coinage of silver would bring financial ruin to America, or at least financial ruin to the pocketbooks of the wealthy.

Using his vast resources and power, Hanna directed a campaign based on fear of a Bryan victory. McKinley campaigned from his home, leaving the politicking for the party hacks. Bryan revolutionized campaign politics by launching a nationwide whistle-stop effort, making twenty to thirty speeches per day from the back of a train as it stopped in each town along a rail line.

When the results were finally tallied, McKinley beat Bryan by an electoral vote margin of 271 to 176. The popular vote was much closer. McKinley won 51% of the vote to Bryan’s 47%.

Many factors led to Bryan’s defeat. He was unable to win a single state in the populous and industrial Northeast. Laborers feared the free silver idea as much as their bosses. While inflation would help the debt-ridden, mortgage-paying farmers, it could hurt the wage-earning, rent-paying factory workers. In a sense, the election came down to a clash between the interests of the city versus country and by 1896, the urban forces won. Bryan’s campaign marked the last time a major party attempted to win the White House by exclusively courting the rural vote.

The economy in 1896 was also on the upswing. Had the election occurred in the heart of the Panic of 1893, the results may have been different. Farm prices were rising by 1896, albeit slowly and the Populist Party fell apart with Bryan’s loss. Although they continued to nominate candidates, most of their membership reverted to the major parties.

The ideas, however, did endure. Although the free silver issue died, the graduated income tax, direct election of senators, initiative, referendum, recall, and the secret ballot were all later enacted. These issues were kept alive by the next standard bearers of reform, the Progressives.

THE PROGRESSIVES

The turn of the 20th Century was an age of reform. Urban reformers and Populists had already done much to raise attention to the nation’s most pressing problems.

America in 1900 looked nothing like America in 1850, yet those in power seemed to be applying the same old strategies to complex new problems. The Populists had tried to effect change by capturing the presidency in 1896 but had failed. The Progressives would succeed where the Populists could not.

The Progressives were urban, northeaster, educated, middle-class, Protestant reform-minded men and women. There was no official Progressive Party until 1912, but progressivism had already swept the nation.

It was more of a movement than a political party, and there were adherents to the philosophy in each major party. There were three progressive presidents: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson. Roosevelt and Taft were Republicans and Wilson was a Democrat. What united the movement was a belief that the laissez faire, Social Darwinist outlook of the Gilded Age was morally and intellectually wrong. Progressives believed that people and government had the power to correct abuses produced by nature and the free market.

The results were astonishing. Seemingly every aspect of society was touched by progressive reform. Worker and consumer issues were addressed, conservation of natural resources was initiated, and the plight of the urban poor was confronted. National political movements such as temperance and women’s suffrage found allies in the progressive movement. The era produced a host of national and state regulations, plus four amendments to the Constitution.

The single greatest factor that fueled the progressive movement in America was urbanization. For years, educated, middle-class women had begun the work of reform in the nation’s cities.

Underlying this new era of reform was a fundamental shift in philosophy away from Social Darwinism. Why accept hardship and suffering as simply the result of natural selection? Humans can and have adapted their physical environments to suit their purposes. Individuals need not accept injustices as the law of nature if they can think of a better way. Philosopher William James called this new way of thinking, pragmatism. His followers came to believe that an activist government could be the agent of the public to pursue the betterment of social ills.

THE SOCIAL GOSPEL

Protestant churches during the Gilded Age were afraid of losing influence over changes in society. Although the population of America was growing rapidly, there were many empty seats in the pews of urban Protestant churches. Middle-class churchgoers were faithful, but large numbers of workers were starting to lose faith in their local churched. The old-style heaven and hell sermons seemed irrelevant to those who toiled long hours for inadequate pay.

Meanwhile, immigration swelled the ranks of Roman Catholic churches. Eastern Orthodox churches and Jewish synagogues were sprouting up everywhere. Many cities reported the loss of Protestant congregations.

Out of this concern grew the Social Gospel Movement. Progressive-minded preachers began to tie the teachings of Christianity with contemporary problems. Christian virtue, they declared, demanded a redress of poverty and despair on earth.

Many ministers became politically active. Washington Gladden, the most prominent of the social gospel ministers, supported the workers’ right to strike in the wake of the Great Upheaval of 1877. Ministers called for an end to child labor, the enactment of temperance laws, and civil service reform. Liberal churches such as the Congregationalists and the Unitarians led the way, but the movement spread to many sects.

The Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) and the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) were founded by Christian Progressives to address the challenges faced by urban youth.

Two new sects formed. Mary Baker Eddy founded the Christian Science, a new variation of Christianity whose followers tried to reconcile religion and science. She preached that faith was a means to cure evils such as disease. The Salvation Army crossed the Atlantic from England and provided free soup for the hungry. More of a service organization than a church, the Salvation Army remains a potent force for good in many American cities.

Middle class women who had time and financial resources became particularly active in the arena of progressive social reform. The Settlement House Movement spread across the country. Women organized and built Settlement Houses in urban centers where destitute immigrants could go when they had nowhere else to turn. Settlement houses provided family-style cooking, lessons in English, and tips on how to adapt to American culture. Primary Source: Painting

Primary Source: Painting

A contemporary painting of Jane Addams who founded Hull House in Chicago and launched the Settlement House Movement.

The first settlement house began in 1889 in Chicago and was called Hull House. Its organizer, Jane Addams, intended Hull House to serve as a prototype for other settlement houses. By 1900 there were nearly 100 settlement houses in the nation’s cities. Jane Addams was considered the founder of social work, a new profession.

The changes were profound. Many historians call this period in the history of American religion the Third Great Awakening. Like the first two awakenings, it was characterized by revival and reform. The temperance movement and the settlement house movement were both affected by church activism. The chief difference between this movement and those of an earlier era was location. These changes in religion transpired because of urban realities, underscoring the social impact of the new American city. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Horrific images from the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire such as this one were published around the nation and spurred workplace safety reforms.

THE TRIANGLE SHIRTWAIST FIRE

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire on March 25, 1911, was the deadliest industrial disaster in the history of New York City and resulted in the fourth-highest loss of life from an industrial accident in American history. The fire caused the deaths of 146 garment workers, who died from the fire, smoke inhalation, or falling or jumping to their deaths. Most of the victims were recent Jewish and Italian immigrant women aged 16 to 23. Of the victims whose ages are known, the oldest victim was 43, and the youngest were just 14.

Because the managers had locked the doors to the stairwells and exits — a common practice at the time to prevent pilferage and unauthorized breaks — many of the workers who could not escape the burning building jumped to the streets below from the eighth, ninth, and tenth floors. The fire led to legislation requiring improved factory safety standards and helped spur the growth of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, which fought for better working conditions for sweatshop workers.

In New York City, a Committee on Public Safety was formed, headed by noted social worker Frances Perkins, to identify specific problems and lobby for new legislation. The subsequent reforms shortened work weeks, instituted mandatory fire escapes, and generally led to safer working conditions. Similar reforms were instituted all around the nation.

CHILD LABOR

One of the most important reforms of the Progressive Era was the elimination of child labor. After its conception in 1904, the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) focused its attacks on child labor and endorsed the first national anti-child labor bill. Although the bill was defeated, it convinced many opponents of child labor that a solution lay in the cooperation and solidarity between the states.

The NCLC called for the establishment of a federal children’s bureau that would investigate and report on the circumstances of all American children. In 1912, the NCLC succeeded in passing an act establishing a United States Children’s Bureau in the Department of Commerce and Labor. On April 9, President William Taft signed the act into law. Over the next thirty years, the Children’s Bureau would work closely with the NCLC to promote child labor reforms on both the state and national level. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

One of the iconic images from the Gilded Age, this photograph of a young girl working at the Lancaster Mills has come to symbolize the thousands of children who worked in factories around the turn of the century rather than attending school.

In 1915, Pennsylvania Congressman A. Mitchell Palmer, who would go on to be Attorney General, introduced a bill to end child labor in most American mines and factories. President Wilson found it constitutionally unsound and after the House voted 232 to 44 in favor on February 15, 1915, he allowed it to die in the Senate. Nevertheless, Arthur Link has called it “a turning point in American constitutional history” because it attempted to establish for the first time “the use of the Commerce Clause commerce power to justify almost any form of federal control over working conditions and wages.”

In 1916, Senator Robert L. Owen of Oklahoma and Representative Edward Keating of Colorado introduced the NCLC backed Keating-Owen Act which prohibited shipment in interstate commerce of goods manufactured or processed by child labor. The bill passed by a margin of 337 to 46 in the House and 50 to 12 in the Senate and was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson. However, in 1918 the law was deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in a five-to-four decision in Hammer v. Dagenhart. The court, while acknowledging child labor as a social evil, felt that the Keating-Owen Act overstepped congress’ power to regulate trade.

The NCLC then switched its strategy to passing of a federal constitutional amendment. In 1924 Congress passed the Child Labor Amendment, however, by 1932 only six states had voted for ratification while twenty-four had rejected the measure. Today, the amendment is technically still-pending and has been ratified by a total of twenty-eight states, requiring the ratification of ten more for its incorporation into the Constitution.

In 1938, the National Child Labor Committee threw its support behind the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) which included child labor provisions designed by the NCLC. The act prohibits any interstate commerce of goods produced through oppressive child labor. The act defines “oppressive child labor” as any form of employment for children under age sixteen and any particularly hazardous occupation for children ages sixteen to eighteen. This definition excludes agricultural labor and instances in which the child is employed by his or her guardians, such as in a family shop. On June 25, 1938, after the approval of Congress, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the bill into law; the FLSA remains the primary federal child labor law to this day. Students who want to work during the school year must first apply for a work permit from their school. Although they may see this as an inconvenience, it is in fact an important protection against the child labor abuses of the past.

EDUCATION REFORM

The Progressives embraced education reform. Employers wanted a better educated workforce to fill ever increasingly technical jobs. Classical liberals believed that public education was the cornerstone of any democracy. A government based on public participation would be imperiled if large numbers of uneducated masses voted unwisely.

Church leaders and modern liberals who were concerned for the welfare of children believed that a strong education was not only appropriate, but an inalienable right. Critics of child labor practices wanted longer mandatory school years. After all, if a child was in school, he or she would not be in the factory.

In 1870, about half of the nation’s children received no formal education whatsoever. Although many states provided for a free public education for children between the ages of 5 and 21, economic realities kept many children working in mines, factories, or on the farm. Only six states had compulsory education laws at this point, and most were for only several weeks per year.

Massachusetts was the leader in tightening laws. By 1890, all children in Massachusetts between the ages of 6 and 10 were required to attend school at least twenty weeks per year. These laws were much simpler to enact than to enforce. Truant officers were necessary to chase down offenders. Private and religious schools had to be monitored to ensure quality standards similar to public schools. Despite resistance, acceptance of mandatory elementary education began to spread. By the turn of the century, such laws were universal throughout the North and West, with only the South lagging behind. There, under the laws of Jim Crow, the public schools in operation in the South were entirely segregated by race in 1900. Mississippi became the last state to require elementary education in 1918.

Other reforms began to sweep the nation. Influenced by German immigrants, kindergartens sprouted in urban areas, beginning with St. Louis in 1873.

The most famous reformer of the time was John Dewey. Dewey applied pragmatic thinking to education. Rather than having students memorize facts or formulas, Dewey proposed “learning by doing.” He emphasized the importance of free, public education in promoting democracy. Dewey also championed the development of normal schools, colleges that specialized in preparation of future teachers. By 1900, one in five public school teachers had a college degree.

More and more high schools were built in the last three decades of the 1800s. During that period, the number of public high schools increased from 160 to 6,000, and the nation’s illiteracy rate was cut nearly in half. Despite the expansion of high schools, still only 4% of American children between the ages of 14 and 17 actually attended a high school. For most Americans, an eighth grade education was sufficient.

Higher education was changing as well. In general, the number of colleges increased, owing to the creation of public land-grant colleges by the states and private universities sponsored by philanthropists, such as Stanford and Vanderbilt.

Opportunities for women to attend college were also on the rise. Mt. Holyoke, Smith, Vassar, Wellesley, and Bryn Mawr Colleges provided a liberal arts education equivalent to their males-only counterparts. By 1910, 40% of the nation’s college students were female, despite the fact that many professions were still closed to women.

Although nearly 47% of the nation’s colleges accepted women, African American attendance at white schools was virtually nonexistent. Black colleges such as Howard, Fisk, and Atlanta University rose to meet this need.

POLITICAL REFORM

The Populist movement influenced progressivism, especially in the promotion of political reform. While rejecting the call for free silver, the progressives embraced the political reforms of secret ballot, initiative, referendum, and recall. Most of these reforms were on the state level. Under the governorship of Robert La Follette, Wisconsin became a laboratory for many of these reforms, enacting them first so other states could see an example to copy.

The Populist ideas of an income tax and direct election of senators became the 16th Amendment and 17th Amendment to the United States Constitution under progressive direction.

Reformers went further by trying to root out urban corruption by introducing new models of city government. The city commission and the city manager systems removed important decision making from politicians and placed it in the hands of skilled technicians. Such reforms did a great deal to reduce the power of political machines like New York’s Tammany Hall.

ENVIRONMENTALISM

As America grew, Americans were destroying its natural resources. Farmers were depleting the nutrients of the overworked soil. Miners removed layer after layer of valuable topsoil, leading to catastrophic erosion. Everywhere forests were shrinking and wildlife was becoming scarcer.

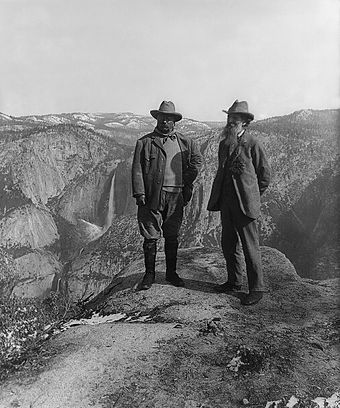

The growth of cities brought a new interest in preserving the old lands for future generations. Dedicated to saving the wilderness, the Sierra Club formed in 1892. John Muir, the president of the Sierra Club, worked valiantly to stop the sale of public lands to private developers. At first, most of his efforts fell on deaf ears. Then Theodore Roosevelt moved into the Oval Office, and his voice was finally heard. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

President Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir at Yosemite National Park in California. The two leaders had a shared interest in conservation and became friends.

Roosevelt was an avid outdoorsman. He hunted, hiked, and camped whenever possible. He believed that living in nature was good for the body and soul. Although he proved willing to compromise with Republican conservatives on many issues, he was dedicated to protecting the nation’s public lands.

The first measure he backed was the Newlands Reclamation Act of 1902. This law encouraged developers and homesteaders to inhabit lands that were useless without massive irrigation works. The lands were sold at a cheap price if the buyer assumed the cost of irrigation and lived on the land for at least five years. The government then used the revenue to irrigate additional lands. Over a million barren acres were rejuvenated under this program.

John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt were more than political acquaintances. In 1903, Roosevelt took a vacation by camping with Muir in Yosemite National Park. The two agreed that making efficient use of public lands was not enough. Certain wilderness areas should simply be left undeveloped.

Under an 1891 law that empowered the President to declare national forests and withdraw public lands from development, Roosevelt began to preserve wilderness areas. By the time he left office 150,000,000 acres had been deemed national forests, forever safe from the ax and saw. This amounted to three times the total protected lands since the law was enacted.

In 1907, Congress passed a law blocking the President from protecting additional territory in six western states. In typical Roosevelt fashion, he signed the bill into law — but not before protecting 16 million additional acres in those six states.

Conservation fever spread among urban intellectuals. By 1916, there were sixteen national parks with over 300,000 annual visitors. The Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts, groups originally founded in England, formed to give urban youths a greater appreciation of nature. Memberships in conservation and wildlife societies soared.

Teddy Roosevelt distinguished himself as the greatest Presidential advocate of the environment since Thomas Jefferson. Much damage had been done, but America’s beautiful, abundant resources were given a new lease on life.

CONCLUSION

When the United States became involved in the First World War, attention was diverted from domestic issues and progressivism went into decline. While unable to solve the problems of every American, the Progressive Era set the stage for the 20th Century trend of an activist government trying to assist its people.

The Progressives were involved in so many different areas of life, that sometimes it can be hard to pin down a definition. Based on what the Progressives of history did, what do you think? What does it mean to be progressive?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: Populists and Progressives tried to reform society around the turn of the last century. They focused on fair business practices, education, political reform, the income tax, aid to the poor, workplace safety, food safety, women’s rights and conservation.

Farmers in the West were upset with the railroad in the late 1800s. They needed railroads to carry their crops to the East where they could be sold to hungry people in growing cities. However, railroads were the only way to move these products, and they were charging enormous rates, so the farmers wanted government to take over the railroads and lower prices. The farmFarmers in the West were upset with the railroad in the late 1800s. They needed railroads to carry their crops to the East where they could be sold to hungry people in growing cities. However, railroads were the only way to move these products, and they were charging enormous rates, so the farmers wanted government to take over the railroads and lower prices. The farmers also wanted inflation which would make it easier for them to repay loans. Thus, they wanted the government to start minting silver money. These two key political goals led to the creation of the Populist Party. A group of farmers led by Jacob Coxey even marched to Washington, DC to demand change. William Jennings Bryan championed these ideas. Although he never won the presidency, Bryan’s Cross of Gold Speech captured the Populists’ grievances. Government regulation of the railroads and free coinage of silver didn’t become law, and eventually, the Democratic Party took on these issues and absorbed the Populist voters.

Other reformers around 1900 were more pragmatic. They looked for small changes they could achieve. These were the Progressives.

Some political reforms did become law. Initiatives, referendums and recalls became law, making it easier for the people to get rid of corrupt politicians and pass laws that politicians might be unwilling to vote for on their own. City commissioners became common as a way to stop political machines. The 17th Amendment provided for the direct election of senators. Before this, the state legislatures had elected senators.

Americans passed the 16th Amendment to made an income tax legal. The graduated income tax required the wealthy to pay a higher percentage of their income than the poor.

Some progressives were inspired by religion. The Social Gospel Movement encouraged people to serve others the way they believed Jesus would have done. They created the YMCA and YWCA. They built settlement houses to help the waves of new immigrants. They opened the Salvation Army to serve the poor. This era of service-minded Christianity is sometimes called the Third Great Awakening.

Other Progressives tried to improve working conditions. The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire showed just how bad working conditions were. These reformers were especially concerned with children who had to work instead of attending school. Although the Keating-Owen Act that was passed at the time was later declared unconstitutional, the Fair Labor Standards Act still stands as protection against exploitation of children as workers.

Progressives worked to improve public education and the first free, public high schools were built.

The first environmentalists emerged. President Theodore Roosevelt helped launch the National Park Service as a means of protecting America’s natural wonders. The Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts were founded, as was the Sierra Club.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Patrons of Husbandry/Grange: Organization of farmers in the late 1800s who, suffering from high shipping costs and debt, advocated for government regulation or railroad rates and the free coinage of silver.

Populist Party: Political party formed in the late 1800s out of the Grange Movement. They advocated for the free coinage of silver, a graduated income tax and government regulation of business. Their leader was William Jennings Bryan. Eventually their members mostly joined the Democratic Party.

Jacob Coxey: The leader of a group of Populist farmers who marched to Washington, DC in 1894 demanding reform.

Coxey’s Army: A group of Populist farmers who marked to Washington, DC in 1894 demanding reform.

William Jennings Bryan: Populist, Progressive, and later democratic leader who championed the rights of farmers. His “Cross of Gold” speech catapulted him to national fame. He ran four times for president but never won.

William McKinley: Republican President first elected in 1896. He defeated William Jennings Bryan. Reelected in 1900, he led the nation through the Spanish-American War, but was assassinated.

Progressives: Groups of people at the turn of the century interested in making change in society, business and government. They were often urban, northeastern, educated, middle class, and protestant.

Progressive Party: A minor political party formed in 1912 to champion progressive issues.

Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA): Organization founded by members of the Social Gospel Movement to give young men a place to improve physical fitness and moral character.

Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA): Organization founded by members of the Social Gospel Movement to give young women a place to improve physical fitness and moral character.

Christian Science: Religious group founded at the turn of the century which tried to find a balance between traditional Christian teaching and new discoveries in science and technology.

Salvation Army: British service organization that was transplanted to America as part of the Social Gospel Movement. They serve the needy by providing shelters for the homeless and soup kitchens.

Jane Addams: Founder of the Settlement House movement.

John Dewey: Advocate for education reform at the turn of the century. He championed the development of normal schools, which were colleges that prepared future teachers.

Robert La Follette: Progressive governor of Wisconsin. He led the way in promoting many reforms in state government.

John Muir: Environmentalist at the turn of the century who became friends with President Theodore Roosevelt and founded the Sierra Club.

Sierra Club: Environmental organization formed in 1892 by John Muir.

Boy Scouts: Organization for boys founded in Britain and brought to America at the turn of the century to promote citizenship and stewardship of the environment.

Girl Scouts: Organization for girls founded in Britain and brought to America at the turn of the century to promote citizenship and stewardship of the environment.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Free Coinage of Silver: Objective of the Populist Party. They wanted inflation to ease loan repayments and asked the government to go off the gold standard. This was the topic of William Jennings Bryan’s famous “Cross of Gold” speech.

Graduated Income Tax: An income tax system in which wealthy individuals pay a higher percentage of their income in taxes than lower class individuals.

Initiative: When citizens can gather signatures and force their legislature to vote on an issue.

Referendum: When citizens can gather signatures and have a proposed law put on a ballot so everyone can vote. This was a way to enact legislation that might otherwise have been prevented by business interests who could pay off elected officials.

Recall: When citizens can gather signatures and force a vote to remove an elected official. This was enacted to curb corruption in government.

Whistle-Stop: Short campaign speeches given from the back of a train car as it stopped in small towns. They were a way spreading a candidate’s message in the days before radio, television or the internet.

Laissez Faire: A government policy toward business that favored low taxes and regulation.

Social Darwinism: An idea common at the turn of the century applying the survival of the fittest concept to human experiences. It argued that people and nations that succeed did so because they were inherently superior to those who lost or were less successful.

Pragmatism: A way of approaching problems developed by William James at the turn of the century. It advocated that people did not need to accept life as it was, but could work for change.

Social Gospel Movement: A movement at the turn of the century based on the belief that helping the poor was a Christian virtue. Members of the movement built settlement houses, formed the YMCA and YWCA and founded the Salvation Army.

Settlement House: A place in large cities where new immigrants could come to learn English, job skills, and find childcare while they worked. The most famous was Hull House in Chicago.

Work Permit: Permission granted from a school for a teenager to work. It is one of the effects of the Fair Labor Standards Act and is designed to protect young Americans from the abuses of child labor.

Normal School: A form of college that would train future teachers. They were especially promoted by John Dewey at the turn of the century.

High School: Free public schools for students after 8th grade. They first became common around the turn of the century.

City Commission: A legislative body for a city. Sometimes called a council, this form of government was a progressive reform and limited the influence of corrupt political machines by allowing voters to select city leaders.

City Manager: A professional selected by a city government who executes policy. This was a progressive reform and sought to separate the decision to spend public money from the awarding of contracts, thus reducing corruption.

![]()

SPEECHES

Cross of Gold Speech: 1896 speech by William Jennings Bryan at the Democratic National convention arguing for the free coinage of silver.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Hull House: The most famous settlement house. It was founded by Jane Addams in Chicago in 1889.

![]()

EVENTS

Panic of 1893: Financial crisis in the 1893.

Third Great Awakening: Term for the general increase in religious practice at the turn of the century. It included the Social Gospel Movement an establishment of organizations such as the Salvation Army, YMCA, YWCA, and Christian Science Church.

Triangle Shirtwaist Fire: A well-publicized fire in New York City in which young women chose to jump to their deaths to escape the flames. Public outrage led to important workplace safety reforms.

![]()

LAWS

Keating-Owen Act: Law passed in 1916 prohibiting the shipment of products across state lines created with child labor. It was struck down as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in Hammer v. Dagenhart in 1918. It was replaced by the Fair Labor Standards Act.

Fair Labor Standards Act: Law passed in 1938 protecting workers, and effectively ending child labor in America.

16th Amendment: Constitutional amendment that made a federal income tax legal.

17th Amendment: Constitutional amendment that provided for the direct election of senators.

GOVERNMENT AGENCIES

National Child Labor Committee (NCLC): Government organization established in 1904 and charged with finding ways to reduce child labor.

Why did many states reject the Child Labor Amendment?

How did Ymcas spread to Hawai’i? Are members now Christian Associates?

Have there been any Presidents since Roosevelt that felt that strongly about protecting natural wilderness? How much more land has been preserved since then?

After the law was passed to block protecting territory, were there any Presidents that decided to break it later on?

Why aren’t people like Jane Addams more known to people today? They worked so hard to push and strive for change yet this was the first time I’ve heard of her??? It seems like we only remember the bad people in history instead of the good….

It’s amazing to think how the Fair Labor Standards Act could have such an influence on America today. Without it, education would have been quite different for all of us.

What was the size of an average class back then?

I don’t understand anti-progressives at all like I know they are just scared of change but do they really expect everything to stay the same forever?

I believe environmentalism has been pushed aside throughout history, as we even got to a point where we brought in young activists to bring attention to the subject and make the effort to reduce the effects of climate change.

What happened to the managers who locked the doors to the exits in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire?

What happened to the Sierra Club today?

Was it necessary to lock in all the people, including to have a one sided lock in the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire incident?

What did Marc Hanna or Mckinley do to overcome Bryan, other than that they did not like the free silver idea.

What compared Mckinley and bryan that eventually made mckinley become president? What made mckinley better?

Who were the first women to encourage colleges to be available to women during the Progressive Era?

What type of pushback was present when children were first getting educated? Did people think the government was too controlling?

How do you think life would be like today if the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) wasn’t signed and turned into a law?

Why are Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts separated? Why was it not just combined?

What kind of degree did different kinds of jobs require? Did nurses and lawyers have to go to school for more years back then than nowadays?

If conservation of our land or natural resources had never occurred or had never taken effect, would we be living in a completely urban-based society today? Would we be suffering from the depletion of our own natural resources?

Do you think the idea Cult of Domesticity still is used today? Most men do work at different types of jobs, and even though women have more job opportunities now, some still stay home because they either need to watch their kids or take care of the house.

What did school and education look like back in the day? Is it similar to now? And do most jobs require education at this time?

Why does the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) take effect only into interstate trade, why not internationally? Is it because their only goal was to abolish child labor specifically in America only and not internationally?

Do you think that being Progressive can also apply to more than just politics? Usually the opposite is considered being traditional, so would being Progressive mean just being more futuristic in our ideas. A lot of things we do nowadays out of politics are also done out of tradition even if it doesn’t make that much sense, does that mean we should change your ways or is it also important to keep our Traditional Values?

Why did the owners of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory not install safety systems for their workers, such as sprinklers, or take other safety precautions?

I found this online resource that gives a little more depth into political reform in America. It also gives a nice summary and it ties together other things that we have read about in this section. There are also some pictures on this resource that could give someone a better understanding of this reform.

Link: http://picturethis.museumca.org/timeline/progressive-era-1890-1920s/progressive-political-reform/info