TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

In modern times, our media world revolves around video, formerly on television or the movie theaters, but increasingly on small screens, and even more so, in video we produce ourselves with smartphones. Before the advent of video, however, the information travelled in print, and the Gilded Age was a great time to be a reader or writer. Millions of Americans wanted something to read and newspapers, magazines and books sold like wildfire.

Of course, not everything that was written back then was worth reading, just as not everything that is posted online now is worth watching. However, in the same way that our cameras today can capture and expose wrongdoing, the writers of the Gilded Age put pen to paper and tried to effect change.

What do you think? Can writers make the world a better place?

THE PRINT REVOLUTION

In a time before the Internet, smart phones, television and even radio, paper was the way Americans communication and found out what was happening in the world. Even very small towns had at least one newspaper, and large cities had dozens. Many newspapers published morning and evening editions and when breaking news happened, news boys in the street could be heard hawing, “Extra! Extra! Read all about it!” as papers put out special editions.

The mail carried magazines, pamphlets, flyers and Americans flocked to newsstands and bookstores. In a time of print, publishing was an enormous business. As Americans streamed into cities from small towns and overseas, journalists realized the economic potential. If half of Boston’s citizens would buy a newspaper three times a week, a publisher could become a millionaire.

The linotype machine, invented in 1883, allowed for much faster printing of many more papers. The market was there. The technology was there. All that was necessary was a group of entrepreneurs bold enough to seize the opportunity. Anybody with a modest sum to invest could buy a printing press and make newspapers. The result was an American revolution in print.

The modern American newspaper took its familiar form during the Gilded Age. To capitalize on those who valued Sunday leisure time, the Sunday newspaper was expanded and divided into supplements. The subscription of women was courted for the first time by including fashion and beauty tips. For Americans who followed the emerging professional sports scene, a sports page was added.

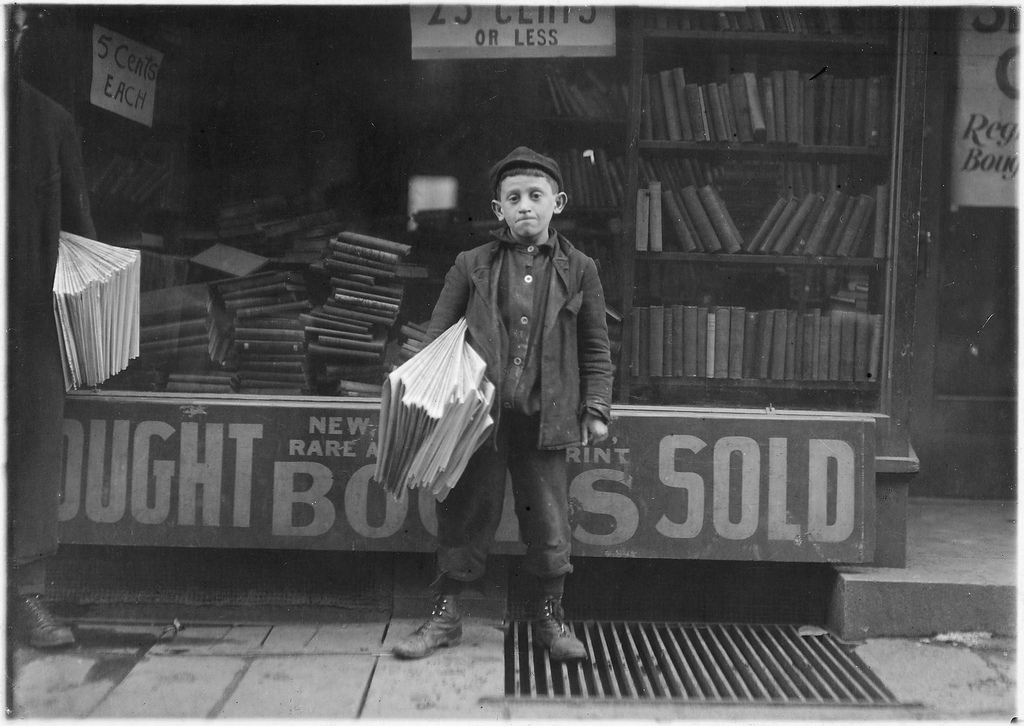

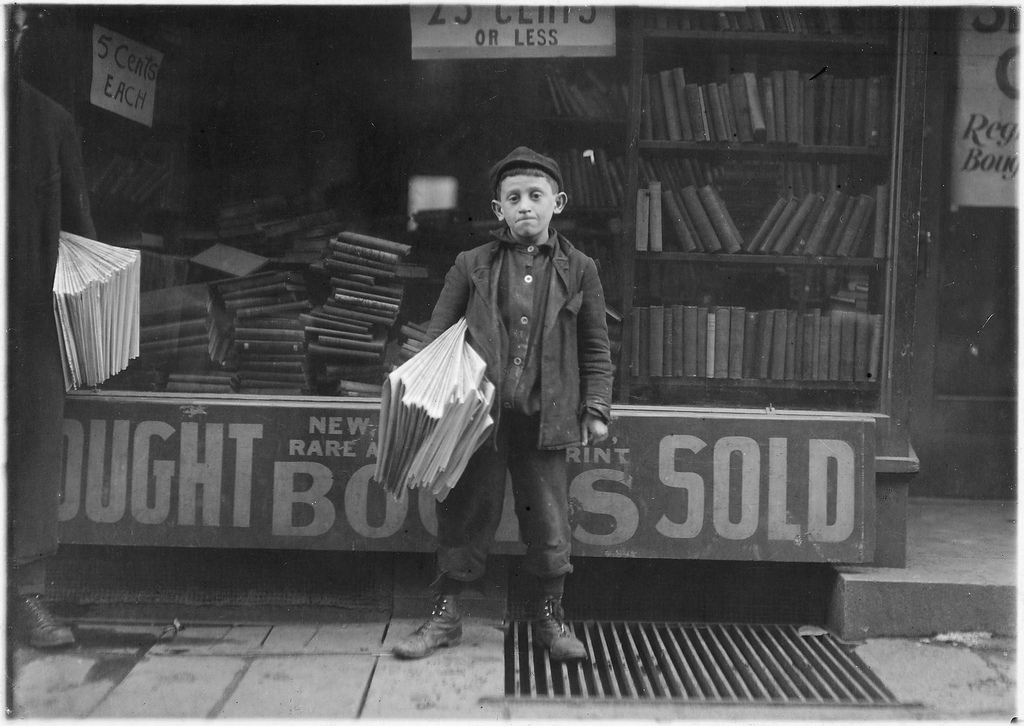

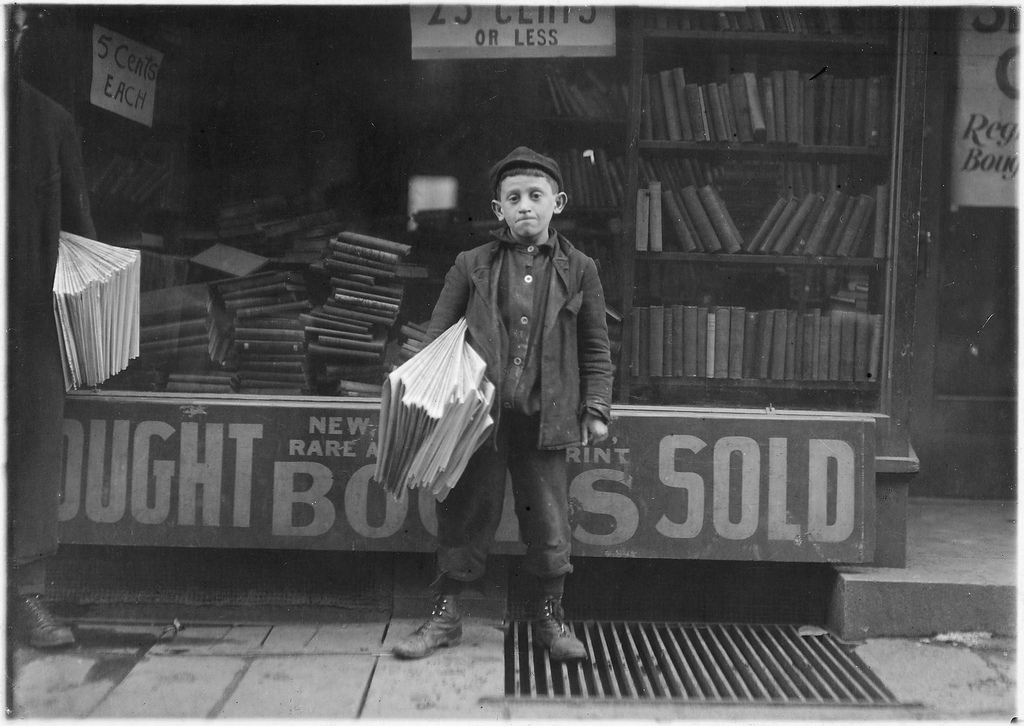

Dorothea Dix, the pen name of Elizabeth Gilmer, became the nation’s first advice columnist for the New Orleans Picayune in 1896. To appeal to those completely disinterested in politics and world events, Charles Dana of the New York Sun invented the human interest story. These articles often retold a heart-warming everyday event like it was national news. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

One of the many newsboys who hawked newspapers in the cities at the turn of the century. This was a common form of child labor.

THE YELLOW PRESS

Competition for readers was fierce, especially in New York. The two titans of American publishing were Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst. These men stopped at nothing to increase their readership. If a news story was too boring, why not twist the facts to make it more interesting? If the truth was too bland, why not spice it up with some innocent fiction? If all else failed, the printer could always increase the size of the headlines to make a story seem more important.

This kind of sensationalism was denounced by veteran members of the press corps. Labeled Yellow Journalism by its critics, this practice was prevalent in late-19th century news. At its most harmless, it bent reality to add a little extra excitement to everyday life. At its most dangerous, it fired up public opinion and helped push America into war with Spain.

Nevertheless, as a business strategy, it worked. Pulitzer increased the daily circulation of the Journal from 20,000 to 100,000 in one year. By 1900, it had increased to over a million.

Joseph Pulitzer purchased the New York World in 1883 after making the St. Louis Post-Dispatch the dominant daily in that city. Pulitzer strove to make the New York World an entertaining read, and filled his paper with pictures, games and contests that drew in new readers. Crime stories filled many of the pages, with headlines like “Was He a Suicide?” and “Screaming for Mercy.” In addition, Pulitzer charged readers only two cents per issue but gave readers eight and sometimes 12 pages of information. The only other two cent paper in the city never exceeded four pages.

While there were many sensational stories in the New York World, they were by no means the only pieces, or even the dominant ones. Pulitzer believed that newspapers were public institutions with a duty to improve society, and he put the World in the service of social reform.

Just two years after Pulitzer bought it, the World became the highest circulation newspaper in New York. Older publishers, envious of Pulitzer’s success, began criticizing the World, harping on its crime stories and stunts while ignoring its more serious reporting. Charles Dana, editor of the New York Sun, attacked The World and said Pulitzer was “deficient in judgment and in staying power.”

Pulitzer’s approach made an impression on William Randolph Hearst, a mining heir in California who acquired the San Francisco Examiner from his father in 1887. Hearst read the World while studying at Harvard University and resolved to make the Examiner as bright as Pulitzer’s paper.

Under his leadership, the Examiner devoted 24% of its space to crime, presenting the stories as morality plays, and sprinkled adultery and risqué illustrations on the front page. A month after Hearst took over the paper, the Examiner ran this story about a hotel fire:

“HUNGRY, FRANTIC FLAMES. They Leap Madly Upon the Splendid Pleasure Palace by the Bay of Monterey, Encircling Del Monte in Their Ravenous Embrace From Pinnacle to Foundation. Leaping Higher, Higher, Higher, With Desperate Desire. Running Madly Riotous Through Cornice, Archway and Facade. Rushing in Upon the Trembling Guests with Savage Fury. Appalled and Panic-Striken the Breathless Fugitives Gaze Upon the Scene of Terror. The Magnificent Hotel and Its Rich Adornments Now a Smoldering heap of Ashes. The Examiner Sends a Special Train to Monterey to Gather Full Details of the Terrible Disaster. Arrival of the Unfortunate Victims on the Morning’s Train — A History of Hotel del Monte — The Plans for Rebuilding the Celebrated Hostelry — Particulars and Supposed Origin of the Fire.”

It was classic yellow press style.

Hearst could be hyperbolic in his crime coverage; one of his early pieces, regarding a “band of murderers,” attacked the police for forcing Examiner reporters to do their work for them. However, while indulging in these stunts, the Examiner also increased its space for international news, and sent reporters out to uncover municipal corruption and inefficiency.

The work of the reporters and the popularity of newspapers could result in more than just interesting reading. In one well-remembered story, Examiner reporter Winifred Black was admitted into a San Francisco hospital and discovered that indigent women were treated with “gross cruelty.” The entire hospital staff was fired the morning the piece appeared.

With the success of the Examiner established by the early 1890s, Hearst began looking for a New York newspaper to purchase, and acquired the New York Journal in 1895, a penny paper which Pulitzer’s brother Albert had sold to a Cincinnati publisher the year before. Primary Source: Newspaper

Primary Source: Newspaper

A classic example of the Yellow Press style, featuring bold, sensational headlines.

Metropolitan newspapers started going after department store advertising in the 1890s, and discovered the larger the circulation base, the better. This drove Hearst; following Pulitzer’s earlier strategy, he kept the Journal’s price at one cent (compared to The World’s two cent price) while providing as much information as rival newspapers. The approach worked, and as the Journal’s circulation jumped to 150,000, Pulitzer cut his price to a penny, hoping to drive his young competitor into bankruptcy.

In a counterattack, Hearst raided the staff of the World in 1896. While most sources say that Hearst simply offered more money, Pulitzer, who had grown increasingly abusive to his employees, had become an extremely difficult man to work for, and many World employees were willing to jump at the chance to get away from him.

Although the competition between the World and the Journal was fierce, the papers were temperamentally alike. Both supported Democrats, both were sympathetic to labor and immigrants and both invested enormous resources in their Sunday publications, which functioned like weekly magazines, going beyond the normal scope of daily journalism.

Their Sunday entertainment features included the first color comic strip pages, and some theorize that the term yellow journalism originated there. Hogan’s Alley, a comic strip revolving around a bald child in a yellow nightshirt, nicknamed The Yellow Kid, became exceptionally popular when cartoonist Richard F. Outcault began drawing it in the World in early 1896. When Hearst predictably hired Outcault away, Pulitzer asked artist George Luks to continue the strip with his characters, giving the city two Yellow Kids. The use of yellow journalism as a synonym for over-the-top sensationalism apparently started with more serious newspapers commenting on the excesses of “the Yellow Kid papers.”

Perhaps ironically, the Pulitzer Prize, which was established by Pulitzer in his will, is awarded every year to recognize outstanding journalism in such categories as Breaking News, Investigative Reporting, and Editorial Cartoons.

MUCKRAKERS

Journalists at the turn of the century were powerful. The print revolution enabled publications to increase their subscriptions dramatically. Writing to Congress in hopes of correcting abuses was slow and rarely produced results. Publishing a series of articles had a much more immediate impact. Collectively called muckrakers, a brave cadre of reporters exposed injustices so grave they made the blood of the average American run cold.

The first to strike was Lincoln Steffens. In 1902, he published an article in McClure’s magazine called “Tweed Days in St. Louis.” Steffens exposed how city officials used the city’s public tax dollars to make deals with big business in order to maintain power. More articles followed, and soon Steffens published the collection as a book entitled The Shame of the Cities. Public outcry from outraged readers led to reform of city government and gave strength to the progressive ideas of a city commission or city manager system.

Ida Tarbell struck next. One month after Lincoln Steffens launched his assault on urban politics, Tarbell began her McClure’s series entitled “History of the Standard Oil Company.” She outlined and documented the cutthroat business practices behind John Rockefeller’s meteoric rise. Tarbell’s motives may also have been personal. Her own father had been driven out of business by Rockefeller.

John Spargo’s 1906 “The Bitter Cry of the Children” exposed hardships suffered by child laborers, such as these coal miners. “From the cramped position [the boys] have to assume,” wrote Spargo, “most of them become more or less deformed and bent-backed like old men…”

Once other publications saw how profitable these exposés had been, they courted muckrakers of their own. In 1905, Thomas Lawson brought the inner workings of the stock market to light in “Frenzied Finance.” John Spargo unearthed the horrors of child labor in “The Bitter Cry of the Children” in 1906. That same year, David Phillips linked 75 senators to big business interests in “The Treason of the Senate.” In 1907, William Hard went public with industrial accidents in the steel industry in the blistering “Making Steel and Killing Men.” Ray Stannard Baker revealed the oppression of Southern blacks in “Following the Color Line” in 1908. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

One of the many photographs taken by Jacob Riis in the slums of New York City. Photographs like this one of three homeless boys helped foster sympathy among middle and upper class Americans and foster the progressive agenda to address the problems faced by the urban poor.

Jacob Riis was a Danish immigrant who moved to New York, and after experiencing poverty and joblessness first-hand, ultimately built a career as a police reporter. In the course of his work, he spent much of his time in the slums and tenements of New York’s working poor. Appalled by what he found there, Riis began documenting these scenes of squalor and sharing them through lectures and ultimately through the publication of his book, How the Other Half Lives, in 1890.

By most contemporary accounts, Riis was an effective storyteller, using drama and racial stereotypes to tell his stories of the ethnic slums he encountered. While his racial thinking was very much a product of his time, he was also a reformer. He felt strongly that upper and middle-class Americans could and should care about the living conditions of the poor. In his book and lectures, he argued against the immoral landlords and useless laws that allowed dangerous living conditions and high rents. He also suggested remodeling existing tenements or building new ones. While other reporters and activists had already brought the issue into the public eye, Riis’s photographs added a new element to the story.

Among the muckrakers was one pioneering female journalist who defied gender stereotypes of the day and became well known for her work uncovering corruption in business and government in New York City. Nellie Bly was catapulted to fame after convincing a judge that she was insane and being remanded to the Blackwell’s Island lunatic asylum where she experienced the terrible treatment women there received. Her subsequent article in the New York World entitled “Ten Days in a Mad-House” secured her a permanent spot among the most respected muckrakers. She later gained national attention and notoriety by embarking on a round-the-world journey in an attempt to beat Phileas Fogg’s fictional record of 80 days from Jules Verne’s famous adventure novel. She completed the journey in 72 days.

Perhaps no muckraker caused as great a stir as Upton Sinclair. An avowed Socialist, Sinclair hoped to illustrate the horrible effects of capitalism on workers in the Chicago meatpacking industry. His bone-chilling account, The Jungle, detailed workers sacrificing their fingers and nails by working with acid, losing limbs, catching diseases, and toiling long hours in cold, cramped conditions. He hoped the public outcry would be so fierce that reforms would soon follow.

The clamor that rang throughout America was not, however, a response to the workers’ plight. Sinclair also uncovered the contents of the products being sold to the general public. Spoiled meat was covered with chemicals to hide the smell. Skin, hair, stomach, ears, and nose were ground up and packaged as head cheese. Rats climbed over warehouse meat, leaving piles of excrement behind.

Sinclair said that he aimed for America’s heart and instead hit its stomach. Even President Roosevelt, who had coined the derisive term muckraker, was propelled to act. Within months, Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act to curb these sickening abuses. Today, the Food and Drug Administration within the Department of Health and Human Services is responsible for monitoring the nation’s food and pharmaceutical supply in order to prevent the problems Sinclair so grotesquely chronicled.

MAGAZINES

Along with newspapers and books, magazines provided Americans with news, information and commentary.

The weekly magazine Puck was founded by Joseph Keppler in St. Louis. It began publishing English and German language editions in March 1871. Five years later, the German edition of Puck moved to New York City, where the first magazine was published in 1876. The English language edition soon followed. The English language magazine continued in operation for more than 40 years under several owners and editors. A typical 32-page issue contained a full-color political cartoon on the front cover and a color non-political cartoon or comic strip on the back cover. There was always a double-page color centerfold, usually on a political topic. Each issue also included numerous black-and-white cartoons used to illustrate humorous anecdotes. A page of editorials commented on the issues of the day, and the last few pages were devoted to advertisements.

Founded by S. S. McClure and John Sanborn Phillips in 1893, McClure’s magazine featured both political and literary content, publishing serialized novels-in-progress, a chapter at a time. In this way, McClure’s published such writers as Willa Cather, Arthur Conan Doyle, Herminie T. Kavanagh, Rudyard Kipling, Jack London, Lincoln Steffens, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Mark Twain. McClure’s published Ida Tarbell’s series in 1902 exposing the monopoly abuses of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company, and Ray Stannard Baker’s earlier look at the United States Steel Corporations. From January 1907 to June 1908, McClure’s published the first detailed history of Christian Science and the story of its founder, Mary Baker Eddy.

Collier’s was another magazine of the time that featured both muckraking journalism and outstanding literary content. In May 1906, the editors commissioned Jack London to cover the San Francisco earthquake, a report accompanied by 16 pages of pictures. Collier’s published the work of investigative journalists such as Samuel Hopkins Adams, Ray Stannard Baker, C.P. Connolly, Upton Sinclair and Ida Tarbell. The work of the writers and editors at Collier’s helped pass reform of child labor laws, slum clearance, food safety and women’s suffrage. Starting October 7, 1905, Collier’s startled readers with “The Great American Fraud,” analyzing the contents of popular patent medicines. The author, Samuel Hopkins Adams, pointed out that the companies producing many of the nation’s medicines were making false claims about their products and some were health hazards. Primary Source: Magazine Cover

Primary Source: Magazine Cover

The Saturday Evening Post was known for featuring illustrated covers highlighting everyday life.

The Saturday Evening Post was founded in 1821 and grew to become the most widely circulated weekly magazine in America. Like its competitors, the magazine published current event articles, editorials, human interest pieces, humor, illustrations, a letter column, poetry and stories by the leading writers of the time. It was known for commissioning lavish illustrations and original works of fiction. Illustrations were featured on the cover and embedded in stories and advertising. Some Post illustrations became popular and continue to be reproduced as posters or prints, especially those by Norman Rockwell. The Post published stories and essays by Ray Bradbury, Agatha Christie, William Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Vonnegut, Louis L’Amour, Sinclair Lewis, Edgar Allan Poe, and John Steinbeck. It also published poetry by such noted poets as Carl Sandburg, Ogden Nash, Dorothy Parker and Hannah Kahn. Jack London’s best-known novel “The Call of the Wild” was first published, in serialized form, in the Saturday Evening Post in 1903.

Weekly magazines such as Puck, McClures, Collier’s and The Saturday Evening Post flourished at the turn of the century, and for nearly half a century. It was not until the 1950s when they lost popularity as Americans turned to a new form of entertainment: television.

CONCLUSION

The printed word in the Gilded Age captured the imagination of America. Sometimes it made us cry, or laugh, or become outraged. But whatever the effect, the editors, illustrators, investigators, and authors of the Gilded Age made a difference. They brought down corrupt politicians and exposed crooked businessmen. They gave us some of America’s great literature.

On the other hand, incendiary headlines fanned war-fever and exaggerated truths in the pursuit of profits.

What do you think? Can writers make the world a better place?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: In the late 1800s, newspaper publishers competing for readers developed the Yellow Press style of sensational headlines and articles. This led to misleading journalism, but also fueled the muckrakers who exposed corruption and scandal in politics and business.

The beginning of the 1900s was a time of growth in the print industry. Before the Internet, radio or television, most people got their news from newspapers, and even small cities had multiple newspapers that were printed twice a day. Two great publishers, Pulitzer and Hearst competed for subscribers and developed a style of sensational journalism that exaggerated the truth and used flashy headlines to catcher potential readers’ attention. Called Yellow Journalism, it was both good and bad.

The Yellow Journalists loved publishing stories that exposed wrongdoing by politicians and business leaders. These muckrakers did America a great service by showing the wrongs of city life, the meat packing industry, robber baron practices, and government corruption. Some of their work led directly to changes in laws that made American better. The best-known example is the connection between Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and the passage of the Meat Inspection and Pure Food and Drug Acts.

This was a time period of growth in magazines as well. Weekly publications such as Puck, McLure’s, Collier’s, and the Saturday Evening Post grew in popularity and remained a staple of American life until after World War II when television replaced reading as a favored pastime.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Journalist: A person who researches, interviews and then writes stories for newspapers, magazines, radio, television, or online publications.

Dorothea Dix: Turn of the century social reformer and journalist. She invented the advice column for newspapers.

Joseph Pulitzer: American newspaper publisher who helped pioneer the style of yellow journalism. His primary rival was William Randolph Hearst.

William Randolph Hearst: American newspaper publisher who helped pioneer the style of yellow journalism. His primary rival was Joseph Pulitzer.

Muckraker: A journalist at the turn of the century who research and published stories and books uncovering political or business scandal. The term was coined by President Theodore Roosevelt.

Lincoln Steffens: Muckraker and author of The Same of the Cities about corruption in city governments.

Ida Tarbell: Muckraker and author of a tell-all book about John D. Rockefeller and the rise of Standard Oil.

Jacob Riis: Muckraker, photographer and author of the book How the Other Half Lives about the life in city slums.

Nellie Bly: Muckraker who wrote about corruption in New York government and business and traveled around the world in 72 days.

Upton Sinclair: Muckraker and author of The Jungle about working and sanitary conditions in meat packing plants in Chicago at the turn of the century.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Human Interest Story: A type of news story that focused on emotional stories rather than breaking news.

Yellow Journalism: A style of newspaper writing pioneered by Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst at the turn of the century featuring bold headlines, images and sensational stories designed to capture readers’ attention and sell papers. This style is generally credited with inflaming public opinion in the lead up to the Spanish-American War.

Pulitzer Prize: An annual award for excellence in journalism, ironically named after one of the trade’s most notorious promoters of the yellow press.

![]()

BOOKS & MAGAZINES

The Shame of the Cities: Lincoln Steffens’ book about corruption in major American cities at the turn of the century.

How the Other Half Lives: Jacob Riis’s book of photographs about life in city slums at the turn of the century.

The Jungle: Upton Sinclair’s book about working and sanitary conditions in meat packing plants in Chicago at the turn of the century.

Puck: Weekly magazine popular at the turn of the century. It was originally published in St. Louis in German.

McClure’s: Weekly magazine popular at the turn of the century that featured literature by famous authors and ran the work of muckrakers including Ida Tarbell’s expose of Standard Oil.

Collier’s: Weekly magazine popular at the turn of the century. It ran numerous stories by muckrakers including The Great American Fraud which exposed abuses in the pharmaceutical industry.

The Saturday Evening Post: Weekly magazine popular at the turn of the century and well into the 1950s. It featured paintings on the cover depicting scenes of daily life, most notably by the artist Norman Rockwell.

![]()

GOVERNMENT AGENCIES

Food and Drug Administration: Organization in the federal government charged with monitoring the food and pharmaceutical industries.

![]()

TECHNOLOGY

Linotype Machine: An 1883 invention that allowed for fast printing of newspapers. It helped lead to a boom in newspaper publishing at the turn of the century.

![]()

LAWS

Pure Food and Drug Act: Law passed in 1906 providing public inspection of food and pharmaceutical production. It was inspired in part by Upton Sinclair’s book The Jungle.

Meat Inspection Act: Law passed in 1906 providing regulation of the meat industry. It was inspired in part by Upton Sinclair’s book The Jungle.