INTRODUCTION

Reconstruction refers to the period following the Civil War of rebuilding the United States. It was a time of great pain and endless questions. On what terms would the Confederacy be allowed back into the Union? Who would establish the terms, Congress or the President? What was to be the place of freed Blacks in the South? Did Abolition mean that Black men would now enjoy the same status as White men? What was to be done with the Confederate leaders, who were seen as traitors by many in the North?

Although the military conflict had ended, Reconstruction was in many ways still a war. This important struggle was waged by radical Northerners who wanted to punish the South and Southerners who desperately wanted to preserve their way of life. Perhaps most of all, Reconstruction was a struggle by formers slaves to define a new life as freedmen.

The North won the war. But in the decade after the war ended, these struggles involved a series of political choices, and countless actions taken by White Southerners, Northerners who travelled to the South, and former slaves. Would their efforts bring about a new, more inclusive and just culture in the South? Would freedom for slaves also mean equality? Or, would slavery end but the same social order go on, with a few wealthy White elites controlling the South, while millions of poor Whites and former slaves occupied the very bottom of the social order? After all the suffering of the war, what would be the final outcome?

What do you think? The North won the war, but who won the peace?

NORTHERN ATTITUDES TOWARD RECONSTRUCTION

The North was split on the question of reconstructing the South. Many Northerners favored a speedy reconstruction with a minimum of changes in the South. Other Northerners, many of them former abolitionists, had the rights of the freedmen and women in mind. That faction favored a more rigorous reconstruction process, which would include consideration of the rights of freed African-Americans.

In the North, with the exception of thousands of shattered families, many with wounded veterans back in their midst, there was little to reconstruct, since most of the fighting was done in the South. Northerners buried their dead, cared for the wounded and did their best to get on with their lives. Although it is safe to say that the majority of Northerners were happy to see slavery gone, if for no other reason than the fact that the divisiveness of the issue had poisoned the political scene for decades, it cannot be assumed that the attitudes of Northerners were friendly to the full incorporation of blacks into the national fabric. Most Northerners did not see Blacks as equals and were not excited about the prospect of millions of former slaves moving to the North. On the other hand, most Northerners did expect the South to accept the verdict of the war and to do whatever would be necessary to reconcile themselves to the end of that “peculiar institution” of slavery. Primary Source: Photograph

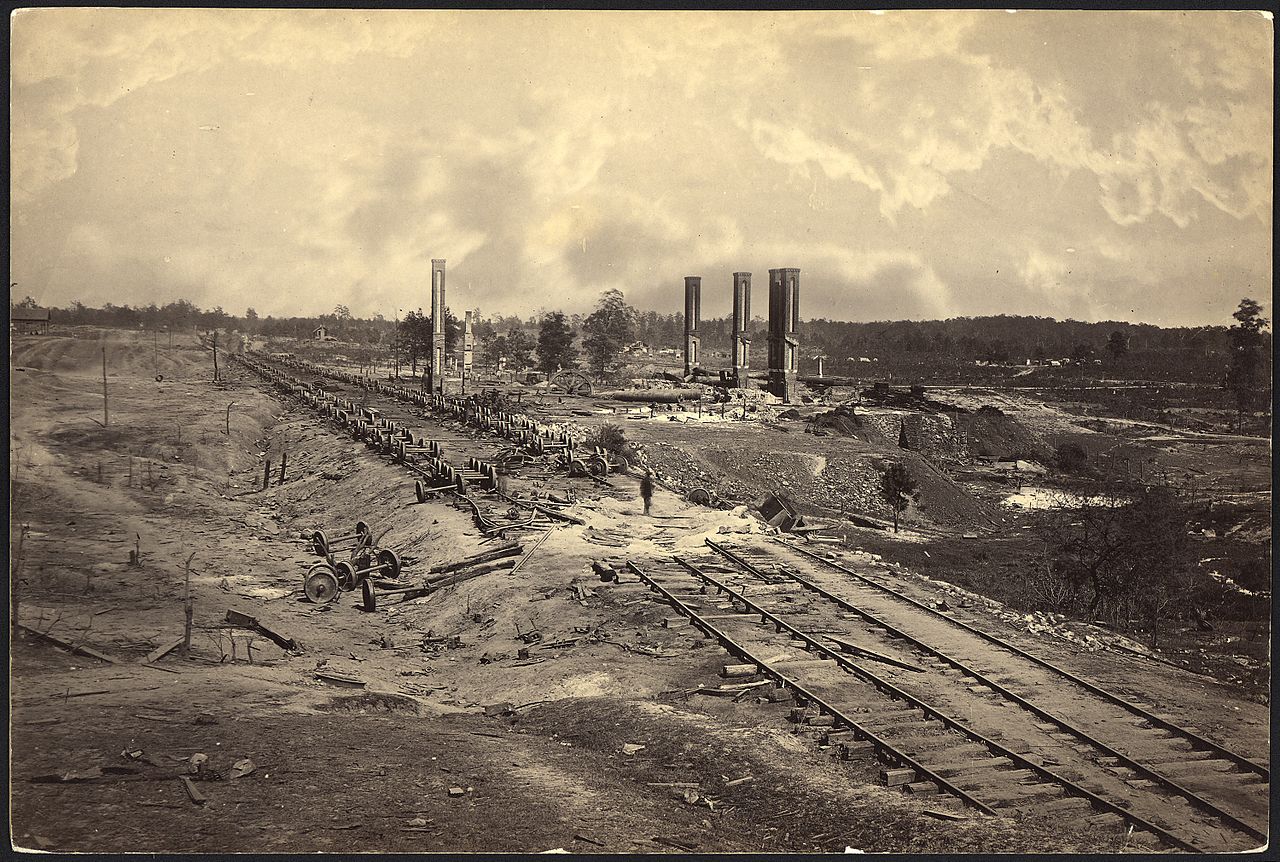

Primary Source: Photograph

A photograph showing the devastation of the South. In this case, the destroyed railroad lines and burned out remains of a building after Sherman and his army passed through the area. This sort of devastation was common across the South.

SOUTHERN ATTITUDES TOWARD RECONSTRUCTION

Many Southerners were enraged at the outcome of the war. Having suffered and bled and died to get out of the Union, they now found themselves back in it. A woman in Richmond wrote in her diary after the hated Yankees raised the American flag over the former Confederate capitol, “I once loved that flag, but now I hate the very sight of it!” Southerners recognized that they had to bow to the results of their loss, but did so with underlying resentment often bordering on hatred. Much ill feeling toward the North existed among the people who had stayed at home, especially in areas invaded by Sherman and others: wives, widows, orphans and those who had endured incredible hardships were particularly horrified to be back under federal control, ruled by their former enemies.

Many Southern whites, having convinced themselves in the prewar years that Blacks were incapable of running their own lives, were also unable to understand what freedom meant to Blacks. As one former slave expressed it, “Bottom rung on top now, Boss.” Many whites were still convinced slavery had been right. In a migration reminiscent of the departure of loyalists after the Revolution, many southerners took their slaves and went to Brazil, where the institution still flourished. Others went west to get as far away from “those damn Yankees” as they could.

THE FREEDMEN AND WOMEN

Many freedmen, the name given to former slaves, who had been restricted all their lives had no “where” to go—although they were elated to be free: the great day of jubilation, it was called—but this new state of freedom also caused confusion. Some stayed on old plantations, others wandered off in search of lost family. Many slave owners were glad to get rid of “burdensome slaves” and threw them out “just like Yankee capitalists.” Some former slaves, especially in cities like Charleston, celebrated their freedom in ways that whites considered “insolent.” They put on fancy clothes, paraded through the streets and showed none of the deferential attitudes that they had shown before the war toward their former masters.

While some Freedmen celebrated openly, others, less trusting, approached their new status with caution. As they quickly learned, there was more to being free than just not being owned as a slave. When asked how it felt to be free by a member of an investigating committee, one former slave said, “I don’t know.” When challenged to explain himself, he said, “I’ll be free when I can do anything a white man can do.” One does not have to be a historian to know that degree of freedom was a long time coming.

For African Americans, the most important single result of War was freedom—”the great watershed of their lives.” Pertinent phrases include: “I feel like a bird out of a cage… Amen… Amen… Amen!” Freedom came “like a blaze of glory.” “Freedom burned in the heart long before freedom was born.” The search for lost families was “awe inspiring.” Some whites claimed that Blacks did not understand freedom and were to be “pitied.” But Blacks had observed a free society, and they knew it meant an end to injustices against slaves. Blacks in the South also had a workable society of their own including churches, families and in time schools as well. A Black culture already existed, and could be adapted to new conditions of freedom. Blacks also took quickly to politics. As one author has put it, they watched the way their former masters voted and then did the opposite. Remarkably, Southern Blacks exhibited little overt resentment against their former masters, and many adopted a conciliatory attitude. When they got into the legislatures they did not push hard for reform.

Much of the South was physically devastated and demoralized after the war. Railroads and factories had been destroyed, farms had gone unattended, and livestock had been killed or driven off in areas occupied by the Union armies. The former plantation owners still had their land but had lost much if not all of their capital. The former slaves comprised a large and experienced labor force but owned neither land nor capital. Many former slaves believed General Sherman’s promise that the federal government was going to supply them with “forty acres and a mule.” Sherman, however, had exceeded his authority, and the Constitution inhibited the ability of the government to confiscate private property “without due process of law.”

Some sort of system of production had to be worked out, and what evolved was a combination of various plans that on the surface seemed reasonable: sharecropping, tenant farming and the crop lien system. Sharecropping meant that those working the land would share the profits from their crop sales with landowners and tenant farmers simply rented the land. Both systems had as their basis a bargain between laborers and the land owners. Each system was potentially beneficial to both parties, but each also contained the possibility of exploitation and fraud, as was shown in practice. Even poor whites became sharecroppers or tenant farmers, so there was nothing inherently discriminatory in any approach. In fact, by 1880 a significant portion of the former slaves had become landowners, and despite exploitation and abuses, the system brought a moderate amount of cooperative self-reliance to the parties involved. Nevertheless, many former slaves still found themselves caught in a system that offered few rewards beyond mere subsistence.

PRESIDENTIAL RECONSTRUCTION

All of these concerns, and the economic devastation of the South were issues that politicians in Washington, DC had to grapple with. In 1864, Republican Abraham Lincoln had chosen Andrew Johnson, a Democratic senator from Tennessee, as his Vice Presidential candidate. Lincoln was looking for Southern support and hoped that by selecting Johnson he would appeal to Southerners who never wanted to leave the Union. Johnson was different from the slave owning elites of the South who had led the Confederacy into secession and war. Johnson, like Lincoln, had grown up in poverty and never owned slaves. He did not learn to write until he was 20 years old. He came to political power as a backer of the small farmer. In speeches, he railed against “slaveocracy” and a bloated “Southern aristocracy” that had little use for the white working man.

The views of the Vice President rarely matter too much, unless something happens to the President. Following Lincoln’s assassination, Johnson’s views now mattered a great deal. Would he follow Lincoln’s moderate approach to reconciliation? Would he support limited black suffrage as Lincoln did? Would he follow the Radical Republicans and be harsh and punitive toward the South?

For the first few years after the war ended, Reconstruction was led by Johnson. Historians have called this period Presidential Reconstruction. Johnson believed the Southern states should decide the course that was best for them. He also felt that African-Americans were unable to manage their own lives. He certainly did not think that African-Americans deserved to vote. At one point in 1866 he told a group of blacks visiting the White House that they should immigrate to another country.

He also gave amnesty and pardon. He returned all property, except, of course, their slaves, to former Confederates who pledged loyalty to the Union and agreed to support the Thirteenth Amendment. Confederate officials and owners of large taxable estates were required to apply individually for a Presidential pardon. Many former Confederate leaders were soon returned to power. Johnson’s vision of Reconstruction had proved remarkably lenient. Very few Confederate leaders were persecuted. By 1866, 7,000 Presidential pardons had been granted.

RADICAL RECONSTRUCTION

While President Johnson sought a gentile, and forgiving Reconstruction, there were Republicans in Congress who were horrified at his approach. These men, dubbed the Radical Republicans believed blacks were entitled to the same political rights and opportunities as whites. They also believed that the Confederate leaders should be punished for their roles in the Civil War. Leaders like Pennsylvania Representative Thaddeus Stevens and Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner vigorously opposed Andrew Johnson’s lenient policies and a great political battle ensued.

Americans had long been suspicious of the federal government playing too large a role in the affairs of states. But the Radicals felt that extraordinary times called for direct intervention in state affairs and laws designed to protect the emancipated blacks. At the heart of their beliefs was the notion that blacks must be given a chance to compete in a free-labor economy. In 1866, this activist Congress also introduced a bill to extend the life of the Freedmen’s Bureau and began work on a Civil Rights Bill.

President Johnson stood in opposition. He vetoed the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, claiming that it would bloat the size of government. He vetoed the Civil Rights Bill rejecting that blacks have the “same rights of property and person” as whites.

The Radical Republicans in Congress grew impatient with President Johnson and began overriding his vetoes. As they grew in political power, they took over the role of leading Reconstruction. This later period has come to be known as Congressional, or Radical Reconstruction. Primary Source: Illustration

Primary Source: Illustration

An illustration of “The Misses Cooke’s school room,” one of many schools operated the South by the Freedman’s Bureau. This illustration appeared in Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper, 1866.

IMPEACHMENT

Impeachment refers to the process specified in the Constitution for trial and removal from office of any federal official accused of misconduct. It has two stages. The House of Representatives charges the official with articles of impeachment. “Treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors” are defined by the Constitution as impeachable offenses. Once charged by the House, the case goes before the Senate for a trial.

In the spring of 1868, Andrew Johnson became the first President to be impeached. The heavily Republican House of Representatives brought 11 articles of impeachment against Johnson. Many insiders knew that the Congress was looking for any excuse to rid themselves of an uncooperative President.

The case against Johnson involved appointed officials and the president’s authority to fire officials who had been approved by the Senate. The affair was clearly a fight for power between Congress and the President, and when Johnson asked for the resignation of Radical Republicans in his Cabinet, it gave his opponents in Congress an excuse to impeach him. Johnson’s defense was simple: only a clear violation of the law warranted his removal. But as with politics, things are rarely simple. One problem was that since Johnson had become president when Lincoln was assassinated, there was no new Vice President to take over.

Eventually, in May of 1868, 35 Senators voted to convict, one vote short of the required 2/3 majority. Seven Republican Senators jumped party lines and found Johnson not guilty. Johnson dodged a bullet and was able to serve out his term. It would be 130 years before another President — Bill Clinton — would be impeached.

THREE AMENDMENTS TO THE CONSTITUTION

Of all of the laws passed during Reconstruction, and all of the political fighting between Congress, the President, and Whites in the South, by far the most important and longest lasting effect was the passage of three amendments to the Constitution.

When President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, he was concerned that the measure might be unconstitutional. Congressional Republicans shared the president’s concerns, in that the proclamation was a war measure and might be invalid once the war was over. At Lincoln’s urging, Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment in 1864. It read, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Lincoln made passage and ratification of the amendment to abolish slavery a campaign issue in the election of 1864 and it was ratified by the requisite number of states in December, 1865.

In March 1865, Congress passed the Trumbull Civil Rights Act, which was designed to counter the Supreme Court decision in the Dred Scott case by granting blacks citizenship. The act affirmed the right of freedmen to make contracts, sue, give evidence and to buy, lease and convey personal and real property. The act excluded state statutes on segregation, but did not provide for public accommodations for blacks. Johnson again vetoed the bill on constitutional grounds and also on the grounds that Southern Congressmen had been absent. Again, he was overridden. Johnson’s vetoes infuriated the Radical Republicans in congress. In June they passed the Fourteenth Amendment because they feared that the Trumbull Civil Rights Act might be declared unconstitutional. The Amendment states, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment was eventually made a condition for states to be readmitted to the Union. The radicals continued to uphold their exclusion of Southern Congressmen on grounds that they excluded Blacks from the political process. Every Southern state legislature except that of Tennessee refused to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment. Instead, they persisted in applying Black Codes to the freedmen and denying them voting and other rights.

In 1869 Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which stated that, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” The amendment was finally ratified in 1870, and well over half a million black names were added to the voter rolls during the 1870s.

Although the Fifteenth Amendment was meant to ensure voting rights for all males, over time, devices such as poll taxes and literacy tests were implemented by White southern leaders to subvert the purpose of the amendment. Poll taxes had to be paid two years in advance, and the financial burden was stiff for blacks. (Poor whites could procure election “loans” to enable them to vote.) Literacy tests were used to restrict blacks, and alternatives such a passing a test on the Constitution were often rigged in favor of whites. By the turn of the century, as a result of such things as amended state constitutions, grandfather clauses and gerrymandering, black voting in the South had been reduced to a fraction of its former numbers. By 1910 few blacks could vote in parts of the South; thus, a vast contrast existed between the earlier goals of the abolitionists and the reality of everyday life for freedmen in the South. This condition persisted until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

VIOLENT OPPOSITION TO RECONSTRUCTION

The changes brought about by Reconstruction, whether led by President Johnson or by the Radical Republicans in Congress, were not met with jubilation by Whites in the South.

In the months following the end of the Civil War many whites carried out acts of random violence against blacks. In their frustration at having lost the war and suffered great loss of life and property, they made the former slaves scapegoats for what they had endured. The violence became more focused when the Ku Klux Klan was founded in December, 1865. The Klan and other white supremacy groups, such as the Knights of the White Camellia, the Red Shirts and the White League, were well underway by 1867. The target of the Klan was the Republican Party, both blacks and whites, as well as anyone who overtly assisted blacks in their quest for greater freedom and economic independence. Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

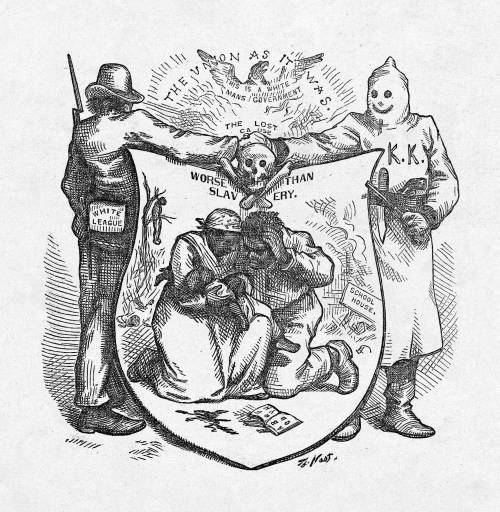

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

An illustration from Harper’s Weekly in 1874. The “supporters” are a member of the White League and a hooded Ku Klux Klansman, shaking hands on the “Lost Cause”.

The result was what can only be called a reign of terror conducted by the Klan and other groups over the following decades. Thousands were killed, injured or driven from their homes or suffered property damage as buildings were burned and farm animals destroyed. Blacks who tried to further the cause of the Republican Party were singled out for attack, as were whites who, for example, rented rooms to northern carpetbaggers, including school teachers. Black men were beaten or lynched in front of horrified family members. The fear of night riders often drove blacks into the woods to sleep because they felt they were not safe in their own homes.

Former Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest, reported to be the first Grand Wizard of the Klan, formally disbanded the KKK in 1868 because of increasing violence. Nevertheless, the group continued to exist and to wreak vengeance upon freedmen and their white supporters. Eventually the Congress passed the Lodge Force Bills in 1870 and 1871 to control the violence and protect Blacks from being deprived of their civil and political rights, but enforcement of those acts was often lax, and other means of intimidation often proved effective.

Despite efforts to control the violence, lynching in the South remained common throughout the 19th and into the 20th century. They were performed in public to further intimidate blacks, who realized that they remained vulnerable, and that the perpetrators would not be punished by a judicial system controlled by Whites, even though it was obvious who the guilty parties were. Almost any action deemed unacceptable by whites could lead to a lynching, including looking too closely at a white woman, talking disrespectfully to whites or simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

THE COMPROMISE OF 1877

By 1876 many people both North and South had grown tired of reconstruction and wanted to forget the Civil War altogether. It had become apparent that the problems of the South could not be resolved by tough federal legislation, no matter how well intended. The country had undergone a long-lasting financial recession beginning in 1873; the Indian Wars were in full swing in the West; the first transcontinental railroad had been completed in 1869, but labor discontent was rising; and immigrants were pouring into the country at an ever-increasing rate. Thus the problems of the South had become something of a distraction. Social equality for Blacks was nonexistent and Congress was losing focus on the issue.

In May 1872, Congress passed a general Amnesty Act, which restored political rights to most remaining confederates. The Democratic Party was restored to control in many Southern states, and black voting rights began to be curtailed.

The election of 1876 was the vehicle by which Reconstruction was finally ended. The candidates were former Union General Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio, Republican, and New York Democratic Governor Samuel Tilden. The campaign was filled with corruption. White supremacy groups helped spread pro-Democratic propaganda throughout the South. As the campaign drew to a close, Tilden was regarded as the favorite, and on the final night of voting, even Hayes believed that he had lost as he retired for the night. It soon became apparent, however, that the results were unclear.

To this day it is not certain who really won. When the electoral votes had been counted, the election returns in three Southern states – South Carolina, Florida and Louisiana – were in question. Charges arose that the election had been stolen in those three states. The apparent results gave those three states to Hayes, which meant that he would have won in the Electoral College by one vote; but if any of those results were overturned, Tilden would have become the victor. The question was: how could the conflict be resolved?

Congress formed a committee to decide what to do. Originally there were supposed to be seven republicans, seven democrats and one independent on the committee, but the independent was deemed ineligible and was replaced by a republican. When the returns in the three states in question were examined, the committee decided to accept the results as presented to Congress, in each case by a vote of 8 to 7. Thus all three states were given over to Hayes.

Democrats in Congress threatened to refuse to accept the committee’s recommendations which would have thrown the nation into turmoil, with no new president to take office. Behind closed doors, in smoke-filled rooms, the Compromise of 1877 was hatched. In return for allowing Hayes to take office as president, the Democrats exacted three promises. First, Reconstruction would be ended and all federal troops would be removed from the South. Second, the South would get a cabinet position in Hayes’s government. Third, money for internal improvements would be provided by the federal government for use in the South.

The irony is that President Hayes probably already planned to do those things, but the Compromise of 1877 was accepted. In April of that year federal troops marched out of the South, turning the freedmen over, as Frederick Douglass put it, to the “rage of our infuriated former masters.”

THE REDEEMERS

Historian Page Smith writes that the Compromise of 1877 which ended Reconstruction “was also a death sentence for the hopes of southern blacks.” Feeling that the North under the radical Republicans in Congress had sought to impose “black rule” on the South, white Southerners set about restoring white supremacy. Their assault on Black rights proceeded on both political and economic ground. Once federal troops left the South, all the advances that had been made for black people during the reconstruction period slowly began to unravel. The Southern governments that took over were dominated by conservative Democrats known as “Redeemers.” Their purpose was to disenfranchise Republicans, black or white, and restore what they viewed as the proper order of things, namely, a society based on white supremacy. The Republican Party soon ceased to exist as a viable political force in the former Confederate states, and Democrats ruled the South for over one hundred years. Secondary Source: Statue

Secondary Source: Statue

The Robert E. Lee Monument in Richmond, Virginia. Completed in 1890, the monument was created by French sculptor Antonin Mercié. Across the South, the many monuments to Confederates like this one serve as a reminder to everyone, especially African Americans, that the “Lost Cause” is still a potent idea. This particular statue was removed in 2021 as a result of nationwide protests in the wake of the murder of George Floyd.

All across the South, Blacks who attempted to exercise their electoral franchise were harassed, intimidated, and even killed to prevent them from voting. Resolutions were passed by groups of white citizens, and editorials appeared in newspapers claiming that Blacks should be excluded from voting because of their political incompetence. Some southern leaders took pride in their attempts to prevent Blacks from voting. One South Carolina leader even bragged of having shot blacks for attempting to vote. Black leaders courageous enough to fight the tide of discrimination were unable even through eloquent pleas for fairness to effect a change in the growing attitude of political discrimination.

As for social equality, during the last quarter of the 19th century, the Southern states passed many “Jim Crow” laws that resulted in segregated public schools and limited black access to public facilities, such as parks, restaurants and hotels. Segregation in the South soon spread to virtually all public entities. As a Richmond Times editorial stated, “God Almighty drew the color line and it cannot be obliterated. The Negro must stay on his side of the line, and the white man on his.” Although African Americans struggled against that imposition of that line for generations, it was not until the great Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s – 100 years after the Civil War – that meaningful progress was made to ensure that Blacks really enjoyed the promises of Reconstruction.

CONCLUSION

Reconstruction came to a close in 1877 and the nation as a whole tried to move on from the long agony of the Civil War. A great deal had changed, but many things had not. In the South a system of segregation enforced by Jim Crow laws replaced slavery. Three amendments to the Constitution had been added, but the promises they made to former slaves were not a reality for many. Women especially were disappointed that the Fifteenth Amendment gave voting rights only men of all races.

After so much bloodshed, before, during, and after the Civil War, we would like to be able to assign winners and losers. Battlefield victors are easy to name. After all, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox. But winning battles and achieving long-term goals are different things entirely. The North defeated the Confederate armies, but did they get what they really wanted? The South lost on the battlefield, but did their worldview win out in the long run?

What do you think? The North won the war, but who won the peace?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: After the war ended in 1865, Northerners tried unsuccessfully to remake Southern society. Although it is often said that the South won Reconstruction, three constitutional amendments were passed that ended slavery, gave citizenship to anyone born in the United States, and guaranteed the right to vote to all men.

After the war, Northerners got on with their lives. There was little evidence in the North that the war had even happened. In the South, most cities had been destroyed. Southerners were surrounded by newly freed former slaves. Reconstruction was very difficult for the South.

African Americans celebrated the end of the Civil War, but faced hardship. Many began looking for lost loved ones. Some hoped to have simple things such as a little land to live on. During the war General Sherman had promised “forty acres and a mule” but this did not happen. Most became share croppers, working land they did as slaves and giving a portion of their harvests as rent. Others worked someone else’s land and paid rent. This new system was only a small step above slavery.

Leaders in the North had different ideas about the proper way to rebuild the South. Lincoln and Andrew Johnson, the new president, wanted to quickly bring the South back into the Union and forgive Southerners who had fought for the Confederacy. He pardoned Southern leaders and returned their property, with the exception of their slaves.

Radical Republicans in Congress wanted to punish Southern leaders and do more to change the social order of the South. They promoted African Americans and spent money to open schools to teach freedmen. They impeached President Johnson when he tried to stop them. He kept his job by one vote, but leadership of Reconstruction switched from the White House to Congress.

Three amendments to the Constitution resulted from the Civil War. The 13th Amendment ended slavery. The 14th Amendment gave citizenship to anyone born in the United States. The 15th Amendment gave all men the right to vote.

Despite these legal gains for African Americans, White southern leaders retook control of their states. They passed laws such as poll taxes and literacy tests. Terrorists groups such as the KKK effectively stopped African Americans from exercising their new freedoms. Reconstruction ended in 1877 when Republicans and Democrats compromised. Hayes was elected president as a Republican and northern troops left the South. Without the army to enforce the ideas of the Radical Republicans, White southern leaders reasserted control and implement the Jim Crow system of segregation. Over time, Redeemers worked to change the meaning of the war. They deemphasized slavery and promoted the idea that Southerners were fighting for freedom. The South may have lost the war, but they won the peace.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Andrew Johnson: Vice President who became President when Lincoln was assassinated. He was from Tennessee and tried to carry out Lincoln’s vision for a forgiving Reconstruction. He was opposed by the Radical Republicans in Congress, impeached but no convicted, and was ineffective.

Carpetbaggers: A nickname for people from the North who came to the South after the war to help with Reconstruction. The name comes from the thick fabric suitcases they carried. In the South, “carpetbagger” is an insult since it refers to an outsider who shows up and tries to tell you how you should live.

Charles Sumner: Leader of the Radical Republicans in the Senate.

Freedmen: Former slaves

Freedmen’s Bureau: The government organization created to help former slaves transition to free life after the war. They are especially remembered for setting up and running schools.

Ku Klux Klan: A White terrorist organization that was formed immediately after the Civil War to counter Northern reconstruction efforts. They attacked African Americans and Republicans. They began to die out as Reconstruction ended, but later became popular again in the 1920s and were an important political force through the 1960s.

Radical Republicans: Members of the Republican Party who were strong abolitionists and wanted to punish the South.

Redeemers: White Democrats in the South who made it was their mission to restore as much of the antebellum social order as possible, including eliminating voting and civil rights for African Americans and establishing the Jim Crow system of segregation.

Rutherford B. Hayes: Republican who became president in 1877.

Samuel Tilden: Democratic Governor of New York. He ran for president in 1876 but lost as a result of the Compromise of 1877.

Tenant Farmer: When farmers pay to live and grow food on someone else’s land.

Thaddeus Stevens: Leader of the Radical Republicans in the House of Representatives.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Amnesty: A general forgiving of crimes for an entire group of people. After the war, former Confederate soldiers were given amnesty from prosecution for treason.

Forty Acres and a Mule: This is what General Sherman promised all freed slaves. Since he had no power to seize property to give to the slaves, he wasn’t able to fulfill his promise.

Grandfather Clause: A rule that stated that if a person’s grandfather had voted, they could also. This was a way to allow poor and illiterate Whites who could not pay poll taxes or pass literacy tests to vote while preventing the descendants of former slaves from voting.

Impeachment: A legal process for removing a president or other elected official because of a crime they have committed.

Literacy Test: A test that a person had to pass in order to vote. White officials were able to manipulate the results so that African Americans didn’t pass the tests and therefore could not vote.

Lynch: To hang a person without a trial. Lynching was used by the KKK and other White terrorist groups to intimidate African Americans.

Pardon: When a president or governor forgives a particular person’s crime.

Poll Tax: A tax a person has to pay in order to vote. It effectively prevents poor people, especially aimed at African Americans, from voting.

Share Cropping: When farm workers use land that belongs to someone else and pay by sharing some of what they grow.

![]()

EVENTS

Presidential Reconstruction: The period immediately after the Civil War ended when reconstruction was based on Lincoln and especially President Andrew Johnson’s lenient and forgiving policies.

Radical Reconstruction: The later period of reconstruction which was led by the Radical Republicans in Congress rather than by President Andrew Johnson.

Compromise of 1877: A deal struck between Republicans and Democrats after the close and contested presidential election between Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel Tilden. Democrats allowed Hayes to become president in return for the end of Reconstruction and the removal of federal troops from the South.

![]()

LAWS

Amnesty Act: A law that gave political, especially voting rights back to former Confederate soldiers.

Civil Rights Bill of 1866: The first major law passed after the Civil War to provide basic rights to all African Americans.

Thirteenth Amendment: The amendment to the Constitution ratified in 1864 that ended slavery.

Fourteenth Amendment: The amendment to the Constitution ratified in 1865 that give citizenship to anyone born in the United States, effectively making former slaves citizens.

Fifteenth Amendment: The amendment to the Constitution ratified in 1869 that guaranteed the right all men regardless of race.

Jim Crow: The nickname for a system of laws that enforced segregation. For example, African Americans had separate schools, rode in the backs of busses, could not drink from White drinking fountains, and could not eat in restaurants or stay in hotels, etc.

Lodge Force Bills: Proposed by Henry Cabot Lodge, these laws provided federal overseers to make sure that African Americans could vote. Later, however, they were rescinded and the Jim Crow system was put into effect.

It’s crazy to see that some things have not changed. Even now, we deal with racism and white supremacy.

What were Johnson’s reasons for wanting to stop opening schools for African Americans?

What are the Jim Crow laws named after?

What kind of measures did the Republicans put in place in case Johnson was actually impeached? Since there would have been no President/Vice President, would a new election be held or would Congress take over part time until a new President was named?

what would have been different if president johnson did not veto the 2 bills?

How might have Reconstruction been changed if Lincoln wasn’t assassinated?

If Congress were to still focus on reconstruction within the South, how much change do you think they would have been able to get done?

I noticed how the power of impeachment has only ever been used three times throughout history which itself is good since we are not prone to presidents with misconduct but makes me wonder if there will be presidents like Johnson that would have almost got impeached.

I find it interesting that the first President ever impeached was the vice president of one of the most liked presidents in modern time.

I have noticed throughout history and even today, no matter what law or rule the government enforces to establish equality, many whites will continue to fight back or disregard them. Black people to this day are still sadly targeted for many things, not as horrible as slavery, but there are still many issues seen today that have never been truly resolved.

This article talks about the Civil War amendments, slavery, and intersectionalism: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-politicalscience/chapter/slavery-and-civil-rights/

What if Andrew Johnson wasn’t the first president to get impeached?

Some people decided to work for their old plantations even after slavery was abolished, why was that?

Did any targets of the KKK ever fight back? Has anyone ever succeeded?

Though both the North and South had different views on reconstruction, why couldn’t there be peace after that? Slavery was now banned and blacks were free people. Views so different should’ve been going in their own path without interference on both ends.

The Southern states passed the Jim Crow laws, but did any Northern states pass that law as well?

What are some things that African-Americans did to celebrate their freedom after the Civil War?

For African Americans the most important single result of the war was freedom. But were there any African Americans who felt the reign of white supremacy and felt that life on the plantation was any better?

Did southerners try to find a way around the laws/ rules made during the reconstruction to try to keep their way of life? It seems like the shift of thought in the south was pretty slow so did this add to them resisting change?

btw, im talking about things like loopholes or being “above the law”

The text just talks about men and women’s life during the civil war, so how about the kids? What did they do in general? Are they able to go to school during the war? Both white kids and black kids?

Why wasn’t the KKK illegal or against the law?

I think the KKK wasn’t illegal because most whites still believed in white supremacy. Whites with power in the government believed in white supremacy, and this prevents illegalizing the KKK.

The hatred that the Southerners had against freedmen and women was quite strong, to the point where they continued to make them suffer or even killed them, despite being granted freedom and new rights. Are the remnants of the Southerners’ hatred the reason why racism against blacks are still continued in the modern American South? Do people in the South today continue to believe in the “Lost Cause”?

Was segregation similar to slavery? Slavery had been where blacks were forced to do labor and that they were separated from each. Segregation was where black were separated from whites. They might have a connection with each other.

In what ways was reconstruction successful and a failure?

There was both success and failure in the Reconstruction Period. One of the main reasons why the Reconstruction was successful is because it restored the United States as a unified nation. It also finally settled the states’ rights vs. federalism debate. But as with the success, there were also failures during this period, such as failing to protect former slaves from white persecution. This is an article that I found that really goes into depth about the successes and failures of this period. It also answers some questions relating to the Civil War.

Link: https://www.sparknotes.com/history/american/reconstruction/study-questions/

Is the reconstruction the result of “a new birth of freedom”?