INTRODUCTION

We often make the mistake of looking back at history and thinking, “of course.” Of course the North was going to win the Civil War. Of course Lincoln would free the slaves. Of course the championship team was going to win!

But we rarely make this mistake when looking into the future. The future seems far less certain. And actually, looking more closely at events from history, the outcome of major events is usually less certain than we think it was. When the Civil War began both the North and the South thought that they would win easily, and they were both wrong. Each side had significant advantages, and had it not been for some key turning points, the outcome of the war might have been very different.

Don’t be too quick to conclude that what did happen is what was going to happen all along.

Could the South have won the Civil War?

STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES

On paper, the Union outweighed the Confederacy in almost every way. Nearly 21 million people lived in 23 Northern states. The South claimed just 9 million people — including 3.5 million slaves — in 11 confederate states. Despite the North’s greater population, however, the South had an army almost equal in size during the first year of the war.

The North had an enormous industrial advantage as well. At the beginning of the war, the Confederacy had only one-ninth the industrial capacity of the Union. But that statistic was misleading. In 1860, the North manufactured 97 percent of the country’s firearms, 96 percent of its railroad locomotives, 94 percent of its cloth, 93 percent of its pig iron, and over 90 percent of its boots and shoes. The North had twice the density of railroads per square mile. There was not even one rifle works in the entire South.

All of the principal ingredients of gunpowder were imported. Since the North controlled the navy, the seas were in the hands of the Union. A blockade could suffocate the South. Still, the Confederacy was not without resources and willpower.

The South could produce all the food it needed, though transporting it to soldiers and civilians was a major problem. The South also had a great nucleus of trained officers. Seven of the eight military colleges in the country were in the South.

The South also proved to be very resourceful. By the end of the war, it had established armories and foundries in several states. They built huge gunpowder mills and melted down thousands of church and plantation bells for bronze to build cannon.

The South’s greatest strength lay in the fact that it was fighting on the defensive in its own territory. Familiar with the landscape, Southerners could harass Northern invaders.

The military and political objectives of the Union were much more difficult to accomplish. The Union had to invade, conquer, and occupy the South. It had to destroy the South’s capacity and will to resist — a formidable challenge in any war. In short, the North had to win. The South simply had to not lose.

Southerners enjoyed the initial advantage of morale: The South was fighting to maintain its way of life, whereas the North was fighting to maintain a union. Slavery did not become a moral cause of the Union effort until Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

When the war began, many key questions were still unanswered. What if the slave states of Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, and Delaware joined the Confederacy? What if Britain or France came to the aid of the South? What if a few decisive early Confederate victories turned Northern public opinion against the war?

Indeed, the North looked much better on paper in terms of resources, but victory for the North was by no means a foregone conclusion.

THEY ALL THOUGHT IT WOULD BE A SHORT WAR

When the war began in April 1861, most Americans in the North and South expected the conflict to be brief. When President Lincoln called upon the governors and states of the Union to furnish him with 75,000 soldiers, he asked for an enlistment of only 90 days. When the Confederacy moved its capital to Richmond, Virginia, 100 miles from Washington, everyone expected a decisive battle to take place on the ground between the two cities.

In the spring of 1861, 35,000 Confederate troops led by General Pierre Beauregard moved north to protect Richmond against invasion. Lincoln’s army had almost completed its 90-day enlistment requirement and still its field commander, General Irvin McDowell, did not want to fight. Pressured to act, on July 18 (three months after the war had begun) McDowell marched his army of 37,000 into Virginia.

Hundreds of reporters, congressional representatives, and other civilians traveled from Washington in carriages and on horses to see a real battle. It took the Northern troops two and a half days to march 25 miles. Beauregard was warned of McDowell’s troop movement by a Southern belle who concealed the message in her hair. He consolidated his forces along the south bank of Bull Run, a river a few miles north of Manassas Junction, and waited for the Union troops to arrive.

Early on July 21, the First Battle of Bull Run began. During the first two hours of battle, 4,500 Confederates gave ground grudgingly to 10,000 Union soldiers. But as the Confederates were retreating, they found a brigade of fresh troops led by General Thomas Jackson waiting just over the crest of the hill.

Trying to rally his infantry, General Bernard Bee of South Carolina shouted, “Look, there is Jackson with his Virginians, standing like a stone wall!” The Southern troops held firm, and Jackson’s nickname, “Stonewall,” was born.

During the afternoon, thousands of additional Confederate troops arrived by horse and by train. The Union troops had been fighting in intense heat — many for 14 hours. By late in the day, they were feeling the effects of their efforts. At about 4 p.m., when Beauregard ordered a massive counterattack, Stonewall Jackson urged his soldiers to “yell like furies.” The Rebel Yell became a hallmark of the Confederate Army. A retreat by the Union became a rout.

Over 4,800 soldiers were killed, wounded, or listed as missing from both armies in the battle. The next day, Lincoln named Major General George B. McClellan to command the new Army of the Potomac and signed legislation for the enlistment of one million troops to last three years. The high esprit de corps of the Confederates was elevated by their victory. For the North, which had supremacy in numbers, it increased their caution. Seven long months passed before McClellan agreed to fight. Meanwhile, Lincoln was growing impatient at the timidity of his generals.

In many ways, the Civil War represented a transition from the old style of fighting to the new style. During Bull Run and other early engagements, traditional uniformed lines of troops faced off, each trying to outflank the other. As the war progressed, new weapons and tactics changed warfare forever. Railroads were used by armies. Metal boats called ironclads replaced wooden warships and leaders sent messages over telegraph.

THE WAR AT HOME: THE NORTH

After initial setbacks, most Northern civilians experienced an explosion of wartime production. During the war, coal and iron production reached their highest levels. Merchant ship tonnage peaked. Traffic on the railroads and the Erie Canal rose over 50%.

Union manufacturers grew so profitable that many companies doubled or tripled their dividends to stockholders. The newly rich built lavish homes and spent their money extravagantly on carriages, silk clothing and jewelry. There was a great deal of public outrage that such conduct was unbecoming or even immoral in times of war. What made this lifestyle even more offensive was that workers’ salaries shrank in real terms due to inflation. The price of beef, rice and sugar doubled from their pre-war levels, yet salaries rose only half as fast as prices while companies of all kinds made record profits.

Women’s roles changed dramatically during the war. Before the war, women of the North already had been prominent in a number of industries, including textiles, clothing and shoe-making. With the conflict, there were great increases in employment of women in occupations ranging from government civil service to agricultural field work. As men entered the Union army, women’s proportion of the manufacturing work force went from one-fourth to one-third. At home, women organized over one thousand soldiers’ aid societies, rolled bandages for use in hospitals and raised millions of dollars to aid injured troops.

Nowhere was their impact felt greater than in field hospitals close to the front. Dorothea Dix, who led the effort to provide state hospitals for the mentally ill, was named the first superintendent of women nurses and set rigid guidelines for quality. Clara Barton, working in a patent office, became one of the most admired nurses during the war and, as a result of her experiences, formed the American Red Cross. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Clara Barton, the founder of the American Red Cross

Resentment of the draft was another divisive issue. In the middle of 1862, Lincoln called for 300,000 volunteer soldiers. Each state was given a quota, and if it could not meet the quota, it had no recourse but to draft men into the state militia. Resistance was so great in some parts of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Wisconsin and Indiana that the army had to send in troops to keep order. Tempers flared further over the provision that allowed exemptions for those who could afford to hire a substitute.

In 1863, facing a serious loss of manpower through casualties and expiration of enlistments, Congress authorized the government to enforce conscription, resulting in riots in several states. In July 1863, when draft offices were established in New York to bring new Irish workers into the military, mobs formed to resist. At least 74 people were killed over three days. The same troops that had just been fighting Lee’s army in the South were deployed to maintain order in New York City.

THE WAR AT HOME: THE SOUTH

After the initial months of the war, the South was plagued with shortages of all kinds. It started with clothing. As the first winter of the war approached, the Confederate army needed wool clothing to keep their soldiers warm. But the South did not produce much wool and the Northern blockade prevented much wool from being imported from abroad. People all over the South donated their woolens to the cause. Soon families at home were cutting blankets out of carpets.

Almost all the shoes worn in the South were manufactured in the North. With the start of the war, shipments of shoes ceased and there would be few new shoes available for years. The first meeting of Confederate and Union forces at Gettysburg arose when Confederates were investigating a supply of shoes in a warehouse.

Money was another problem. The South’s decision to print more money to pay for the war led to unbelievable increases in price of everyday items. By the end of 1861, the overall rate of inflation was running 12% per month. For example, salt was the only means to preserve meat at this time. Its price increased from 65¢ for a 200 pound bag in May 1861 to $60 per sack only 18 months later. Wheat, flour, corn meal, meats of all kinds, iron, tin and copper became too expensive for the ordinary family. Profiteers frequently bought up all the goods in a store to sell them back at a higher price. It was an unmanageable situation. Food riots occurred in Mobile, Atlanta and Richmond.

Over the course of the war, inflation in the South caused women’s roles to change dramatically. The absence of men meant that women were now heads of households. Women staffed the Confederate government as clerks and became schoolteachers for the first time. Women at first were denied permission to work in military hospitals as they were exposed to “sights that no lady should see.” But when casualties rose to the point that wounded men would die in the streets due to lack of attention, female nurses such as Sally Louisa Tompkins and Kate Cumming would not be denied. Indeed, by late 1862, the Confederate Congress enacted a law permitting civilians in military hospitals, giving preference to women.

The most unpopular act of the Confederate government was the institution of a draft. Like in the North, loopholes permitted a drafted man to hire a substitute, leading many wealthy men to avoid service. When the Confederate Congress exempted anyone who supervised 20 slaves, dissension exploded. Many started to conclude that it was “a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.” This sentiment and the suffering of their families led many to desert the Confederate armies. By November 1863, James Seddon, the Confederate Secretary of War said he could not account for 1/3 of the army. Soldiers worried more about their families than staying to fight for their new country. Much of the Confederate army deserted and went home to pick up the pieces of their shattered lives.

DIPLOMACY: THE IMPORTANCE OF EUROPEAN POWER

Rebellions rarely succeed without foreign support. When the Americans launched their revolution against British rule in the 1770s, French support was crucial to their success. The North and South both sought British and French support. Jefferson Davis was determined to secure such an alliance with Britain or France for the Confederacy. Abraham Lincoln knew this could not be permitted. A great chess match was about to begin.

Cotton was a formidable weapon in Southern diplomacy. Europe was reliant on cotton grown in the South for their textile industry. Over 75% of the cotton used by British mills came from states within the Confederacy.

By 1863, the Union blockade reduced British cotton imports to 3% of their pre-war levels. Throughout Europe there was a cotton famine. There was also a great deal of money being made by British shipbuilders. The South needed fast ships to run the blockade, which British shipbuilders were more than happy to furnish.

France had reasons to support the South. Napoleon III saw an opportunity to get cotton and to restore a French presence in America, especially in Mexico, by forging an alliance.

But the North also had cards to play. Crop failures in Europe in the early years of the war increased British dependency on Union wheat. In 1862, over one-half of British grain imports came from the Union. The growth of other British industries such as the iron and shipbuilding offset the decline in the textile industry. British merchant vessels were also carrying much of the trade between the Union and Great Britain, providing another source of income.

The greatest problem for the South lay in its embrace of slavery, as the British took pride in their leadership of ending the trans-Atlantic slave trade. To support a nation that had openly embraced slavery now seemed unthinkable. After Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation and freed slaves in the rebelling states, Britain was much less prepared to intervene on behalf of the South.

The key for each side was to convince Europe that victory for its side was inevitable. Early Southern victories convinced Britain that the North couldn’t triumph against a foe so large and so opposed to domination. This was a lesson reminiscent of the one learned by the British themselves in the Revolutionary War. Yet, despite all its victories, the South never struck a decisive blow to the North. The British felt they must know that the South’s independence was certain before recognizing the Confederacy. The great Southern loss at Antietam in 1862 loomed large in the minds of European diplomats.

Yet efforts did not stop. Lincoln, his Secretary of State William Seward, and Ambassador Charles Francis Adams labored tirelessly to maintain British neutrality. As late as 1864, Jefferson Davis proposed to release slaves in the South if Britain would recognize the Confederacy, but it was too little too late. Britain and France never took sides.

GETTYSBURG: THE TURNING POINT OF THE WAR

As the years dragged on, Robert E. Lee developed a strategy to end the war. He proposed to take the offensive, invade the northern state of Pennsylvania, and defeat the Union Army in its own territory. Such a victory would relieve Virginia of the burden of war, strengthen the hand of Peace Democrats in the North, and undermine Lincoln’s chances for reelection. It would reopen the possibility for European support that was closed at Antietam. And perhaps, it would even lead to peace.

The result of this vision was the largest battle ever fought on the North American continent. This was Gettysburg, where more than 170,000 fought and over 40,000 were casualties.

Lee began his quest in mid-June 1863, leading 75,000 soldiers out of Virginia into south-central Pennsylvania. Forty miles to the south of Lee, the new commander of the Union Army of the Potomac, General George Meade, headed north with his 95,000 soldiers. When Lee learned of the approach of this concentrated force, he sent couriers to his generals with orders to reunite near Gettysburg to do battle. As sections of the Confederate Army moved to join together, Confederate General A.P. Hill, heard a rumor that that there was a large supply of shoes at Gettysburg. On July 1, 1863, he sent one of his divisions to get those shoes. The battle of Gettysburg was about to begin.

As Hill approached Gettysburg from the west, he was met by the Union cavalry of John Buford. Couriers from both sides were sent out for reinforcements. By early afternoon, 40,000 troops were on the battlefield, aligned in a semicircle north and west of the town. At noon on July 2, the second day of the battle, Lee ordered his divisions to attack but the Union soldiers were able to prevent defeat.

Lee was determined to leave Pennsylvania with a victory. On the third day of battle, he ordered a major assault against the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. Confederate cannon batteries started to fire into the Union center. The firing continued for two hours. At 3 p.m., 14,000 Confederate soldiers under the command of General George Pickett began their famous charge across three-quarters of a mile of open field to the Union line.

Few Confederates made it and the attack has often been called the High Tide of the Confederacy. Lee’s attempt for a decisive victory in Pennsylvania had failed. He had lost 28,000 troops — one-third of his army. A month later, he offered his resignation to Jefferson Davis, which was refused. Meade had lost 23,000 soldiers. The hope for Southern recognition by any foreign government was dashed. The war continued for two more years, but Gettysburg marked the end of Lee’s major offensives. Secondary Source: Illustration

Secondary Source: Illustration

An artist’s illustration of a scene from Pickett’s Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg published in 1896.

THE LONG, SLOW END OF THE WAR

Only one day after their victory at Gettysburg, Union forces captured Vicksburg, the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. Lincoln and Union commanders began to make plans for finishing the war. The Union strategy to win the war did not emerge all at once. By 1863, however, the Northern military plan consisted of five major goals:

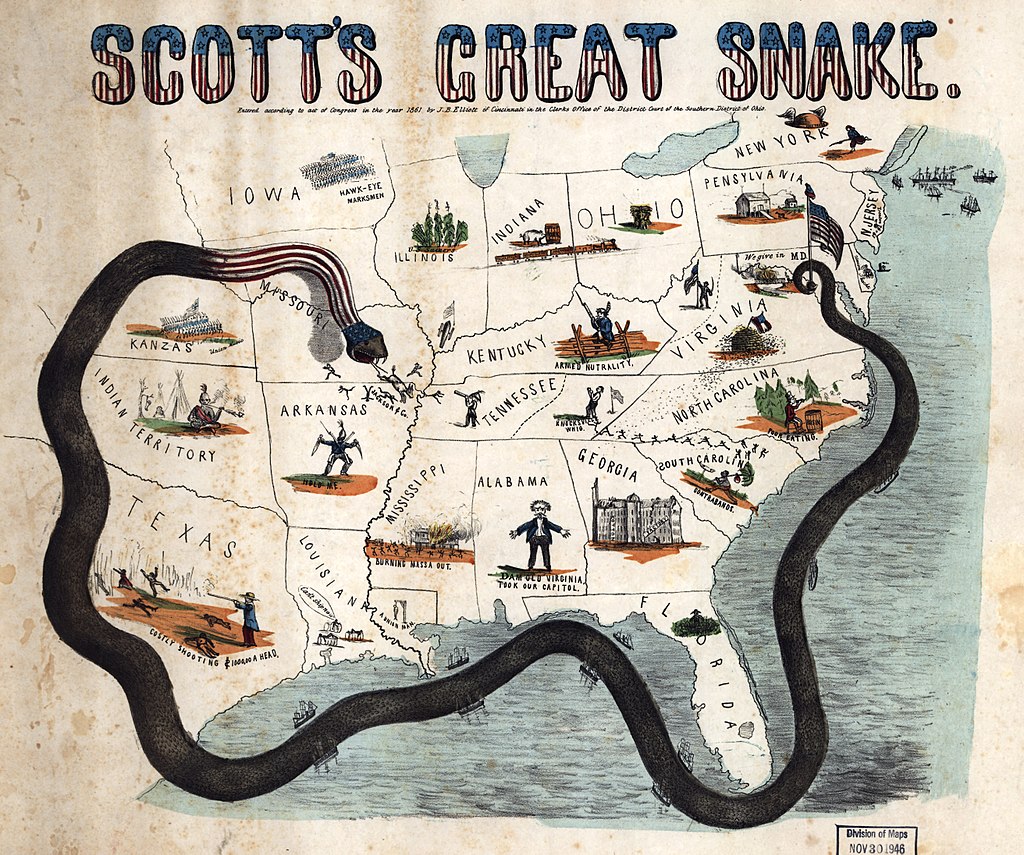

First, blockade all Southern coasts. This strategy, known as the Anaconda Plan, would eliminate the possibility of Confederate help from abroad.

Second, control the Mississippi River. The river was the South’s major inland waterway. Also, Northern control of the rivers would separate Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas from the other Confederate states.

Third, capture Richmond. Without its capital, the Confederacy’s command lines would be disrupted.

Fourth, shatter Southern civilian morale by capturing and destroying the cities of Atlanta, Savannah, and the heart of Southern secession, the State of South Carolina.

Finally, Lincoln and his generals planned to use the numerical advantage of Northern troops to engage the enemy everywhere to break the spirits of the Confederate Army. Primary Source: Illustration

Primary Source: Illustration

A drawing from 1861 depicting the Anaconda Plan. General Winfield Scott developed the plan.

By early 1864, the first two goals had been accomplished. The blockade had successfully prevented any meaningful foreign aid and also prevented the South from exporting any of its cotton, thus starving it of badly needed cash. General Ulysses S. Grant‘s success at Vicksburg delivered the Mississippi River to the Union. Lincoln turned to Grant to finish the job and, in the spring of 1864, appointed Grant to command the entire Union Army.

Grant had a plan to end the war by November. He mounted several major simultaneous offensives. General George Meade was to lead the Union’s massive Army of the Potomac against Robert E. Lee. Grant would stay with Meade, who commanded the largest Northern army. General James Butler was to advance up the James River in Virginia and attack Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy. General William Tecumseh Sherman was to plunge into the heart of the South, inflicting as much damage as he could against their war resources.

Meade faced Lee’s army in Virginia. Lee’s strategy was to use terrain and fortified positions to his advantage, thus decreasing the importance of the Union’s superiority in numbers. He hoped to make the cost of trying to force the South back into the Union so high that the Northern public would not stand for it.

But, unlike the Union commanders of the past, Grant had the determination to press on despite the cost. Twenty-eight thousand soldiers were casualties of the Battle of the Wilderness. A few days later, another 28,000 soldiers were casualties in the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House. More than two-thirds of the casualties of these battles were Union soldiers.

At Cold Harbor the following week, Grant lost another 13,000 soldiers — 7,000 of them in half an hour. In the 30 days that Grant had been fighting Lee, he lost 50,000 troops — a number equal to half the size of the Confederate army at the time. As a result, Grant became known as “The Butcher.” Congress was appalled and petitioned for his removal. But Lincoln argued that Grant was winning the battles and refused to grant Congress’s request.

Butler failed to capture Richmond, and the Confederate capital was temporarily spared. On May 6, 1864, one day after Grant and Lee started their confrontation in the Wilderness, Sherman entered Georgia, scorching whatever resources that lay in his path. By late July, he had forced the enemy back to within sight of Atlanta. For a month, he lay siege to the city. Finally, in early September he entered Atlanta — one day after the Confederate army evacuated it.

Sherman waited until seven days after Lincoln’s hotly fought reelection before putting Atlanta to the torch and starting his army’s March to the Sea. No one stood before him. His soldiers pillaged the countryside and destroyed everything of conceivable military value as they traveled 285 miles to Savannah, Georgia in a march that became legendary for the misery it created among the civilian population. On December 22, 1864 Savannah fell. When he arrived, Sherman sent a telegram to President Lincoln saying, “I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah…”

Next, Sherman ordered his army to move north into South Carolina. Their intent was to destroy the state where secession began. Exactly a month later, its capital, Columbia, fell to him. On the same day, Union Forces retook Fort Sumter. The war was almost over. Primary Source: Illustration

Primary Source: Illustration

A drawing published in Harper’s Weekly depicting the burning of Columbia, South Carolina by General Sherman’s troops.

THE ELECTION OF 1864

It is hard for modern Americans to believe that Abraham Lincoln, one of history’s most beloved Presidents, was nearly defeated in his reelection attempt in 1864. Yet by that summer, Lincoln himself feared he would lose. How could this happen? First, the country had not elected an incumbent President for a second term since Andrew Jackson in 1832 — nine Presidents in a row had served just one term. Also, his embrace of emancipation was still a problem for many Northern voters.

Despite Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg a year earlier, the Southern armies came back fighting with a vengeance. During three months in the summer of 1864, over 65,000 Union soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing-in-action. In comparison, there had been 108,000 Union casualties in the first three years. General Ulysses S. Grant was being called The Butcher. At one time during the summer, Confederate soldiers came within five miles of the White House.

Lincoln had much to contend with. He had staunch opponents in the Congress. Underground Confederate activities brought rebellion to parts of Maryland. Lincoln’s suspension of the writ of habeas corpus was ruled unconstitutional by Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney — an order Lincoln refused to obey.

Meanwhile the Democratic Party split, with major opposition from Peace Democrats, who wanted a negotiated peace at any cost. They chose as their nominee George B. McClellan, Lincoln’s former commander of the Army of the Potomac. Even Lincoln expected that McClellan would win.

The South was well aware of Union discontent. Many felt that if the Southern armies could hold out until the election, negotiations for Northern recognition of Confederate independence might begin.

Everything changed on September 6, 1864, when General Sherman seized Atlanta. The war effort had turned decidedly in the North’s favor and even McClellan now argued for continuing the war and achieving military victory instead of trying to negotiate a peace agreement with the Confederacy. Two months later, Lincoln won the popular vote that eluded him in his first election. He won the electoral college by 212 to 21 and the Republicans won three-fourths of Congress. A second term and the power to conclude the war were now in his hands.

APPOMATTOX: THE SOUTH SURRENDERS

After Sherman’s victory in Savannah, only Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia remained as a substantial military force to oppose the Union Army. For nine months, Grant and Lee had faced each other from 53 miles of trenches during the Siege of Petersburg. Lee’s forces had been reduced to 50,000, while Grant’s had grown to over 120,000.

The Southern troops began to melt away as the end became clear. On April 2, Grant ordered an attack on Petersburg and broke the Confederate line. Lee and his shrinking army were able to escape but Lee sent a message to Jefferson Davis saying that Richmond could no longer be defended and that he should evacuate the city. That night Jefferson Davis and his cabinet set fire to everything of military value in Richmond, then boarded a train to Danville, 140 miles to the south. Mobs took over the streets and set more fires. The next day, Northern soldiers arrived. And one day after that, Lincoln visited the city and sat in the office of Jefferson Davis.

Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, now reduced in size to 35,000 troops, had escaped to the west. They were starving, and Lee had asked the Confederate Commissary Department to have rations for his infantry waiting at the Amelia Courthouse. But when he arrived there, no rations awaited his troops. The Confederate government had no money to buy food for its army, and even if it did, there was no food to be found and no way to deliver it to its hungry troops. Lee and his men were forced to forage the countryside for food. The delay caused by his need to acquire food proved fatal to the Confederate effort.

Now 125,000 Union soldiers were surrounding Lee’s army, whose numbers had been reduced to 25,000 troops and were steadily falling. Still, Lee decided to make one last attempt to break out. On April 9, the remaining Confederate Army, under John Gordon, drove back Union cavalry blocking the road near the village of Appomattox Court House. But beyond them were 50,000 Union infantry, and as many or more were closing in on Lee from his rear. It was over and Lee knew it.

Lee sent a note to Grant, and later that afternoon they met in the home of Wilmer McLean. Grant offered generous terms of surrender. Confederate officers and soldiers could go home, taking with them their horses, side arms, and personal possessions. Also, Grant guaranteed their immunity from prosecution for treason. At the conclusion of the ceremony, the two men saluted each other and parted. Grant then sent three days’ worth of food rations to the 25,000 Confederate soldiers. The official surrender ceremony occurred three days later, when Lee’s troops stacked their rifles and battle flags. The war was over, and the hard road toward rebuilding the South began.

CONCLUSION

The war ended in total defeat for the South. Their armies were defeated on the battlefield. Their cities were destroyed. Their economy was devastated by the loss of slave labor and a crippling blockade. But did it have to end that way? Could the South have done things differently to produce a different outcome? If Lincoln and the leaders of the Union armies had made different choices would the war have ended differently?

What do you think? Could the South have won the Civil War?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The North and South both had advantages and weaknesses in the Civil War, but eventually the North’s industrial might and willingness to persevere through a long and destructive war led to victory.

The North and South each had strengths and weaknesses going into the Civil War. The North was more populous, industrialized and wealthy. However, the North had to take the fight to the South and win. The South simply had to hold out until the North gave up. The Southerners saw themselves as fighting for their freedom, which was an ideological advantage in the beginning. Later in the war, Northerners saw their armies as marching to end slavery, a moral crusade of their own. Most of the nation’s best generals were from the South. The lack of effective leadership made the North’s efforts in the first years of the war mostly ineffective.

In order to prevent the South from exporting its cotton to Europe, the North implemented a blockade of Southern ports.

Both sides believed it would be a short war. After the first battles, it became clear that this would not be the case. Although the Union general McClellan was an excellent organizer and trained a professional army, he was hesitant to take it into battle and failed to destroy the smaller Confederate army early in the war even when he had the chance.

In the North, the war helped some become rich. Vast federal expenditures led to an increase in industrial output. Although many men volunteered at the start of the war, Lincoln instituted a draft as the war dragged on which led to rioting. In the South, a blockade by the Union navy choked off trade and led to hunger and food riots by southern women. In both the North and South, the wealthy found ways to avoid the fighting, while women found new roles in industry, farming and the war effort. Women founded the Red Cross during the war.

Southern leaders had hoped to use the cotton trade to convince England and France to recognize their independence. Lincoln successfully avoided this by exporting northern wheat and reminding the English that the South was fighting to preserve slavery, a practice the English had recently banned.

The turning point of the war was the Battle of Gettysburg. Although neither side won, Robert E. Lee lost more men than he could replace, and it was the last time he would attempt to take his army into the North or try to capture Washington, DC. At that same time, Union armies in the South captured Vicksburg, thus gaining control of the Mississippi River and dividing the South in half.

During the war, Lincoln won reelection. Although he had violated the Constitution, he won because the war was going well in 1864 and because democrats were split between those who supported the war, and those who wanted to make a deal for peace with the South.

It took two more years of fighting after Gettysburg to finally destroy the South. General Sherman marched his Union army through Georgia, destroying everything he could in the first example of modern total warfare. General Grant eventually destroyed the Confederate capital of Richmond and forced Lee to surrender.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

George McClellan: General who led the Union army at the start of the war. He infuriated Lincoln with his unwillingness to lead his troops into battle. Eventually Lincoln fired him.

Army of the Potomac: The Union army that did most of the fighting in Virginia against General Lee. It was named after the Potomac River that separates Maryland and Virginia.

American Red Cross: An organization that provides free healthcare and support to soldiers and people affected by war or disaster. It was founded by Clara Barton during the Civil War.

Clara Barton: Nurse and founder of the American Red Cross.

Peace Democrats: Also called Copperheads, they were Democrats in the North who wanted to end the war and make peace with the South.

Ulysses S. Grant: General who led the Union armies at the end of the war. He won the Battle of Vicksburg and Lincoln promoted him to commander of all of the Union Armies. He accepted Lee’s surrender at the end of the war and later was elected president.

William Tecumseh Sherman: Northern general who led his army through the South destroying everything he could – farms, railroads, etc. – in an effort to prevent the South from having the means of waging war.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Blockade: Using a navy to prevent ships from entering or exiting a port.

Draft: A process in which the government forces people to join the military.

Inflation: When the prices of good increase over time.

Anaconda Plan: The North’s strategy to blockade Southern ports to prevent trade and resupply.

High Tide of the Confederacy: A term used to describe the Battle of Gettysburg, and especially Pickett’s Charge. It was the closest the South ever came to military victory in the war. Although far from over, after the battle the war turned in the North’s favor.

Terms of Surrender: The agreement made by two armies or nations to formally end a war.

Writ of Habeas Corpus: A legal term that means “Show me the Body.” It means that the government cannot accuse you of a crime and then hold you in jail indefinitely before giving you a trial.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Confederacy: The Confederate States of America. The slave-holding states from the South that seceded.

Union: The United States of America. The North including the four border states which had slaves but did not secede.

Appomattox Court House: The small town in Virginia where Lee surrendered to Grant.

Richmond: The capital city of Virginia and the Confederacy.

![]()

EVENTS

First Battle of Bull Run: The first major battle between the armies of the North and South. It ended in a victory for the South and demonstrated that neither side would have an easy victory.

Draft Riots: Riots that happened in 1863 in major cities of the North, especially in New York City when the government enforced conscription into the army. They demonstrated that the war was not universally popular.

Battle of Gettysburg: The turning point battle of the war. Lee led his army into Pennsylvania hoping to force the North to give up, but lost the battle.

Battle of Vicksburg: A major victory for the Union army in the South. Vicksburg was a city along the Mississippi River. After it fell to the North, the Union controlled shipping on the river and was able to split the South in two.

Food Riots: Riots that occurred in the major cities of the South, especially led by women when the blockade of Southern ports by the Union navy prevented enough food from being imported. These were also sometimes called the Bread Riots.

Pickett’s Charge: Lee’s final attack on the third day of the Battle of Gettysburg. Often called the High Tide of the Confederacy, it was a disaster for the South, ending in defeat and the loss of thousands of troops.

Sherman’s March to the Sea: In 1864 General Sherman led his Union army through Georgia destroying everything he could. He started in Atlanta and his destination was the city of Savannah on the coast. He became of a hero of the North and villain across the South.

Siege of Petersburg: The long attack on the City of Petersburg south of Richmond, Virginia. It was devastating for both armies, but due to the South’s inability to replace lost soldiers, proved to be a death blow to Lee’s army.

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/election-1864 (This link gives more information about the Election of 1864)

How did the south try to retaliate against the blockades of the ports?

How many Southerners supported the Union, were anti-slavery, or decided to switch sides during the war to fight with the North?

Why were soldiers only sent with 3 days worth of food?

Lincoln sitting in the office of Jefferson Davis is the perfect example of pettiness done with class.

How was Lee able to retreat and escape with so many soldiers, when they had completely lost battles?

Here is more information about the intention to suspend the writ of habeas corpus:

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/lincolns-suspension-of-habeas-corpus-is-challenged#:~:text=On%20April%2027%2C%201861%2C%20Lincoln,deemed%20threatening%20to%20military%20operations.

Why did Sherman feel the need to burned down Atlanta? Did something happen to him before that made them hate the South or was he just a fierce abolitionist?

What did Union soldiers think of Ulysses S. Grant?

How would have foreign influences affected the war’s outcome?

What if the south won the Civil War? Would that change the way America is today? Would slavery still be a thing in 2021?

Due to the drafts and conscriptions being implemented, were there any government officials that had to go out into the war?

How did Butler fail to capture Richmond?

If France and Britain were more involved in the Civil War, would things be different?

If one surrendered earlier, would that decrease the amount of battles that happened and would that have weakened one society?

How did Clara Barton form the American Red Cross with her experiences?

What would it look like if the Union just let the South establish the Confederacy States without starting the war?

It is interesting to see how the Confederate Army started in a smaller size than the Union Army but still tried to win. It seems like the South began with more weaknesses than the North. The South couldn’t distribute food which played a crucial role in the war. Was the loss of the Confederate Army inevitable or was it the military strategies that led to their loss? Although it is worth noting the determination of the South to win the war, it seems selfish to drive these soldiers to death even after beginning to realize their loss.

Why were Peace Democrats called Copperheads?

If cotton or rice was never produced or exported, would there still have been slavery? I mean, there were lots of other crops to grow so probably yes, but these two were the main ones that were grown in the South. Along with that, would the economy be as good without cotton or rice?

I believe slavery would have still happened because before cotton or rice they had agricultural goods to farm off of but I don’t believe the economy would have been as good because cotton was considered a weapon for the South and it was a way the nation could grow through trades and the industrial revolution. The South needed European support so they minimized the import of cotton by 3% which caused the cotton famine in Europe. When the South needed ships to run the blockade, the British were happy to furnish.

Why was there so much backlash to the civil war draft up to the point where there were mobs and riots? Did people not believe in the union? Did they think the cause was not worth dying/ killing for?

There were several reasons as to why the Civil War draft had escalated to many violent mobs and riots. I don’t think it was because the people didn’t believe in the Union, but I think it is because they lived in a constant state of fear with the war and its outcome. For example, the wealthy people could avoid service by paying $300 for a substitute. This began the statement that it was “A rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.” Another reason could be that many newspapers & pro-slavery politicians had incited unrest in the white-working class. Some of the people had feared that if the Union won the war, the big wave of free black people throughout the Union would likely compete for jobs with working-class whites. Here is the link I used to better my understanding about why some of the people in the Union had acted this way:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/civil-war-draft-riots-brought-terror-new-yorks-streets-180964905/

Reading about the Civil War years ago at the moment feels oddly familiar. Currently during the presidential election it seems that the country is divided once again, with much violence that seems to follow some of the disagreements. It’s scary how this is something of the past but I feel that it is also coming back in the present. I hope there will not be a Civil War II because right now I am quite worried.

Did Lee automatically agree to any terms he was given, or did he try to get some things to his advantage?

What happened to the slaves during the Civil War? Where they forced to be drafted in the military like the rest of the White men?

In the South slaves were not forced to draft in the Army. Instead they were used as enslaved labor. In the North Black men, both free and escaped slaves willingly offered themselves to fight for the Union. Here is a link to an article that I read to better understand what was happening to the slaves and free blacks in the Union.

https://emancipation.dc.gov/page/slavery-military

Did Southern states’ disadvantages make them realize how much they lag in industrial development ?