INTRODUCTION

For generations American leaders had dealt with the question of slavery without resorting to war. The Founding Fathers found a way to deal with it – the 3/5 Compromise, and Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, and Daniel Webster had negotiated the Missouri Compromise and Compromise of 1850 to prevent war.

There were undoubtedly great leaders in the 1850s as well. Stephen Douglas, Henry Ward Beecher, William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglas were all well respected voices of the day. But what made them different from the leaders of the past? Was it them, or had times changed? Could Clay, Calhoun and Webster have succeeded in the 1850s?

Then there’s Abraham Lincoln, elected president in 1860. We regard him as one of our greatest presidents, but it was his election that prompted the Southern states to secede. He tried to convince the leaders of the South to give him a chance, but to no avail. And when they seceded he decided to go to war to prevent them from forming their own nation. Could he have done things differently to avoid war? Should he have just let them leave?

What do you think? Could American leaders have prevented the Civil War?

THE FUGITIVE SLAVE ACT

By 1843, several hundred slaves a year were successfully escaping to the North along the routes of the Underground Railroad, making slavery untenable in the border states. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 required the return of runaway slaves by requiring authorities in free states to return fugitive slaves to their masters. However, many Northern states found ways to circumvent the Fugitive Slave Act. Some jurisdictions passed “personal liberty laws,” which mandated a jury trial before alleged fugitive slaves could be moved. Others forbade the use of local jails or the assistance of state officials in the arrest or return of alleged fugitive slaves. In some cases, juries refused to convict individuals who had been indicted under federal law.

The Missouri Supreme Court held that voluntary transportation of slaves into free states, with the intent of their residing there permanently or definitely, automatically made them free, whereas the Fugitive Slave Act dealt with slaves who went into free states without their master’s consent. Furthermore, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842) that states did not have to offer aid in the hunting or recapture of slaves, which greatly weakened the law of 1793. These and other Northern attempts to sidestep the 1793 legislation agitated the South, which sought stronger federal provisions for returning slave runaways.

In response to the weakening of the original fugitive slave law, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made any federal marshal or other official who did not arrest an alleged runaway slave liable to a fine of $1,000. In addition, officers who captured a fugitive slave were entitled to a bonus or promotion for their work, and any person aiding a runaway slave by providing food or shelter was subject to a six-month imprisonment and a $1,000 fine. Law-enforcement officials everywhere now had greater incentive to arrest anyone suspected of being a runaway slave, and sympathizers had much more to risk in aiding those seeking freedom. Slave owners only needed to supply an affidavit to a federal marshal to claim that a slave had run away. The suspected runaway could not ask for a jury trial or testify on his or her own behalf. As a result, many free black people were accused of running away and were forced into slavery.

The Fugitive Slave Act was met with violent protest in the North. This anger stemmed less from the fact that slavery existed than from Northern fury at being coerced into protecting the institution of Southern slavery. Moderate abolitionists were faced with the choice of defying what they believed to be an unjust law or breaking with their own consciences and beliefs, and many became radical antislavery proponents as a result. Many Northerners viewed the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act as evidence that the South was conspiring to spread slavery through federal coercion and force regardless of the will of Northern voters. In many Northern towns, slave catchers were attacked, and mobs set free captured fugitives. Two prominent instances in which abolitionists set free captured fugitives include John McHenry in Syracuse, New York, in 1851, and Shadrach Minkins in Boston of the same year.

THE DRED SCOTT DECISION

For abolitionists, helping runaway slaves escape was one thing, but the idea that slavery might be permitted anywhere in the United States, even within the North was terrifying. What if a slave owner brought a slave into the North? Would that person still be a slave? What did the Constitution say on this subject? This question was raised in 1857 before the Supreme Court in case of Dred Scott v. Sanford. Dred Scott was a slave of an army surgeon, John Emerson. Scott had been taken from Missouri to posts in Illinois and what is now Minnesota for several years in the 1830s, before returning to Missouri. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 had declared the area including Minnesota free. In 1846, Scott sued for his freedom on the grounds that he had lived in a free state and a free territory for a prolonged period of time. Finally, after eleven years, his case reached the Supreme Court. At stake were answers to critical questions, including slavery in the territories and citizenship of African-Americans. The verdict was a bombshell.

The Court ruled that Scott’s “sojourn” of two years to Illinois and the Northwest Territory did not make him free once he returned to Missouri.

The Court further ruled that as a black man Scott was excluded from United States citizenship and could not, therefore, bring suit. According to the opinion of the Court, African-Americans had not been part of the sovereign people who made the Constitution.

The Court also ruled that Congress never had the right to prohibit slavery in any territory. Any ban on slavery was a violation of the Fifth Amendment, which prohibited denying property rights without due process of law.

The Missouri Compromise was therefore unconstitutional.

The Chief Justice of the United States was Roger B. Taney, a former slave owner, as were four other Southern justices on the Court. The two dissenting justices of the nine-member Court were the only Republicans. The North refused to accept a decision by a Court they felt was dominated by “Southern fire-eaters.” Many Northerners, including Abraham Lincoln, felt that the next step would be for the Supreme Court to decide that no state could exclude slavery under the Constitution, regardless of their wishes or their laws.

Two of the three branches of government, the Congress and the President, had failed to resolve the issue. Now the Supreme Court rendered a decision that was only accepted in the Southern half of the country. Was the American experiment collapsing? The only remaining national political institution with both Northern and Southern strength was the Democratic Party, and it was now splitting at the seams. The fate of the Union looked hopeless. Primary Source: Photograph

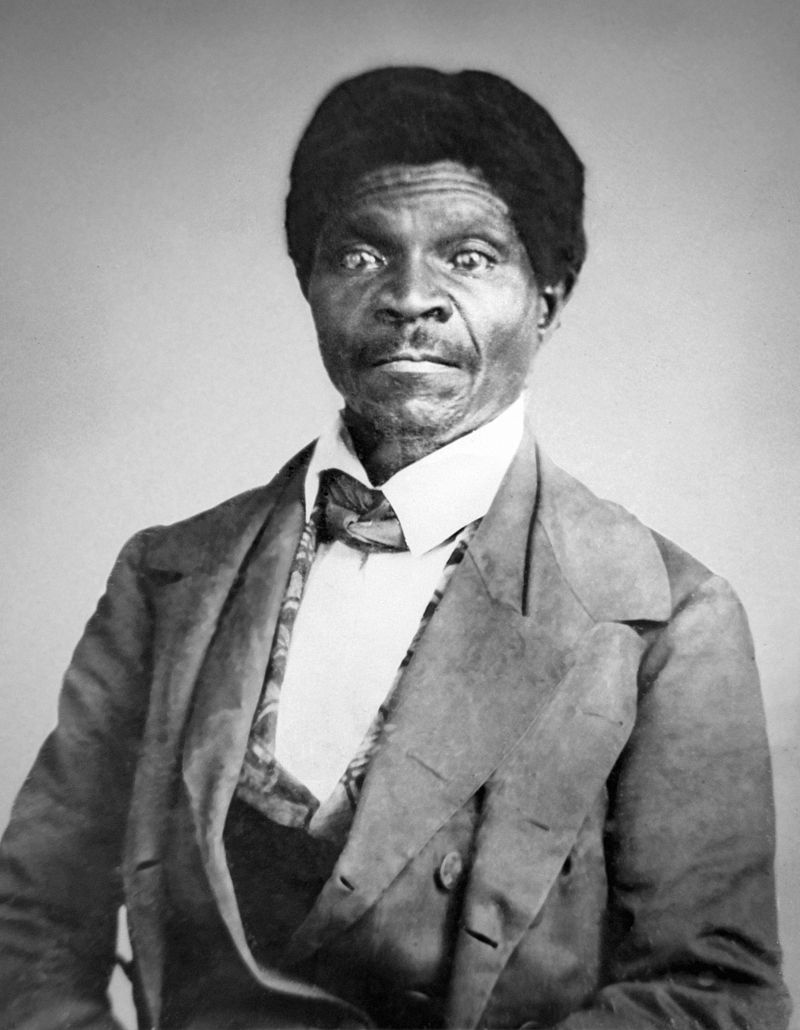

Primary Source: Photograph

A photograph of Dred Scott, taken around the time of his court case in 1857

THE LINCOLN-DOUGLAS DEBATES

In 1858, as the country moved ever closer to disunion, two politicians from Illinois attracted the attention of a nation. From August 21 until October 15, Stephen Douglas battled Abraham Lincoln in face to face debates around the state. The prize they sought was a seat in the Senate. Lincoln challenged Douglas to a war of ideas. Douglas took the challenge. The debates were to be held at seven locations throughout Illinois. The fight was on and the nation was watching.

The spectators came from all over Illinois and nearby states by train, by canal-boat, by wagon, by buggy, and on horseback. They briefly swelled the populations of the towns that hosted the debates. The audiences participated by shouting questions, cheering the participants as if they were prizefighters, applauding and laughing. The debates attracted tens of thousands of voters and newspaper reporters from across the nation.

During the debates, Douglas still advocated popular sovereignty which maintained the right of the citizens of a territory to permit or prohibit slavery. It was, he said, a sacred right of self-government. Lincoln pointed out that Douglas’s position directly challenged the Dred Scott decision, which decreed that the citizens of a territory had no such power.

In what became known as the Freeport Doctrine, Douglas replied that whatever the Supreme Court decided was not as important as the actions of the citizens. If a territory refused to have slavery, no laws, no Supreme Court ruling, would force them to permit it. This sentiment would be taken as betrayal to many Southern Democrats and would come back to haunt Douglas in his bid to become President in the election of 1860.

Time and time again, Lincoln made that point that “a house divided against itself cannot stand.” Douglas refuted this by noting that the founders, “left each state perfectly free to do as it pleased on the subject.” Lincoln felt that blacks were entitled to the rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, which include “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Douglas argued that the founders intended no such inclusion for blacks.

Neither Abraham Lincoln nor Stephen Douglas won a popular election that fall. Under rules governing Senate elections, voters cast their ballots for local legislators, who then choose a Senator. The Democrats won a majority of district contests and returned Douglas to Washington. But the nation saw a rising star in the defeated Lincoln. The entire drama that unfolded in Illinois would be played on the national stage only two years later in the 1860 presidential election.

CIVILITY BREAKS DOWN IN CONGRESS

Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts was an avowed Abolitionist and leader of the Republican Party. After the sack of Lawrence, on May 21, 1856, he gave a bitter speech in the Senate called “the crime against Kansas.” He blasted the “murderous robbers from Missouri,” calling them “hirelings, picked from the drunken spew and vomit of an uneasy civilization.” Part of this oratory was a bitter, personal tirade against South Carolina’s Senator Andrew Butler. Sumner declared Butler an imbecile and said, “Senator Butler has chosen a mistress. I mean the harlot, slavery.” During the speech, Stephen Douglas leaned over to a colleague and said, “that damn fool will get himself killed by some other damn fool.” The speech went on for two days.

Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina thought Sumner went too far. Southerners in the Nineteenth Century were raised to live by an unwritten code of honor. Defending the reputation of one’s family was at the top of the list. A distant cousin of Senator Butler, Brooks decided to teach Charles Sumner a lesson he would not soon forget. Two days after the end of Sumner’s speech, Brooks entered the Senate chamber where Sumner was working at his desk. He flatly told Sumner, “You’ve libeled my state and slandered my white-haired old relative, Senator Butler, and I’ve come to punish you for it.” Brooks proceeded to beat Sumner over the head repeatedly with a gold-tipped cane. The cane shattered as Brooks rained blow after blow on the hapless Sumner, but Brooks was not deterred. Only after being physically restrained by others did Brooks end the pummeling. Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

A lithograph cartoon published in 1855 depicting Preston Brooks’ attack on Charles Sumner in the Senate chamber.

Charles Sumner spent years recovering from the attack and Northerners were incensed. The House of Representatives voted to expel Brooks, but it could not amass the votes to do so. Brooks was levied a $300 fine for the assault. He resigned and returned home to South Carolina, seeking the approval of his actions there. South Carolina held events in his honor and reelected him to his House seat. Replacement canes were sent to Brooks from all over the South. This response outraged Northern moderates even more than the caning itself.

As for poor Charles Sumner, the physical and psychological injuries from the caning kept him away from the Senate for most of the next several years. The voters of Massachusetts also reelected him and let his seat sit vacant during his absence as a reminder of Southern brutality. The violence from Kansas had spilled over into the national legislature.

JOHN BROWN’S RAID

On October 16, 1859, John Brown led a small army of 18 men into the small town of Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. His plan was to instigate a major slave rebellion in the South. He would seize the arms and ammunition in the federal arsenal, arm slaves in the area and move South along the Appalachian Mountains, attracting slaves to his cause. He had no rations. He had no escape route. His plan was doomed from the very beginning. But it did succeed to deepen the divide between the North and South.

John Brown and his cohorts marched into an unsuspecting Harper’s Ferry and seized the federal complex with little resistance. It consisted of an armory, arsenal, and engine house. He then sent a patrol out into the country to contact slaves, collected several hostages, including the great grandnephew of George Washington, and sat down to wait. The slaves did not rise to his support, but local citizens and militia surrounded him, exchanging gunfire, killing two townspeople and eight of Brown’s company. Troops under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee arrived from Washington to arrest Brown. They stormed the engine house, where Brown had withdrawn, captured him and members of his group, and turned them over to Virginia authorities to be tried for treason. He was quickly tried and sentenced to hang on December 2, 1859.

Brown’s strange effort to start a rebellion was over less than 36 hours after it started; however, the consequences of his raid would last far longer. In the North, his raid was greeted by many with widespread admiration. While they recognized the raid itself was the act of a madman, some Northerners admired his zeal and courage. Church bells pealed on the day of his execution and songs and paintings were created in his honor. Brown was turned into an instant martyr. Ralph Waldo Emerson predicted that Brown would make “the gallows as glorious as the cross.” The majority of Northern newspapers did, however, denounce the raid. The Republican Party adopted a specific plank condemning John Brown and his ill-fated plan. But that was not what the South saw.

Southerners were shocked and outraged. How could anyone be sympathetic to a fanatic who destroyed their property and threatened their very lives? How could they live under a government whose citizens regarded John Brown as a martyr? Southern newspapers labeled the entire North as John Brown sympathizers. Southern politicians blamed the Republican Party and falsely claimed that Abraham Lincoln supported Brown’s intentions. Moderate voices supporting compromise on both sides grew silent amid the gathering storm. In this climate of fear and hostility, the election year of 1860 opened ominously. The election of Abraham Lincoln became unthinkable to many in the South.

THE ELECTION OF 1860

The Democrats met in Charleston, South Carolina, in April 1860 to select their candidate for President in the upcoming election. It was turmoil. Northern democrats felt that Stephen Douglas had the best chance to defeat the “Black Republicans.” Although an ardent supporter of slavery, Southern Democrats considered Douglas a traitor because of his support of popular sovereignty, permitting territories to choose not to have slavery. Southern democrats stormed out of the convention, without choosing a candidate. Six weeks later, the Northern Democrats chose Douglas, while at a separate convention the Southern Democrats nominated then Vice-President John C Breckenridge.

The Republicans met in Chicago that May and recognized that the Democrat’s turmoil actually gave them a chance to take the election. They needed to select a candidate who could carry the North and win a majority of the Electoral College. To do that, the Republicans needed someone who could carry New Jersey, Illinois, Indiana and Pennsylvania — four important states that remained uncertain. There were plenty of potential candidates, but in the end Abraham Lincoln had emerged as the best choice. Lincoln had become the symbol of the frontier, hard work, the self-made man and the American dream. His debates with Douglas had made him a national figure and the publication of those debates in early 1860 made him even better known. After the third ballot, he had the nomination for President.

A number of aging politicians and distinguished citizens, calling themselves the Constitutional Union Party, nominated John Bell of Tennessee, a wealthy slaveholder as their candidate for President. These people were for moderation. They decided that the best way out of the present difficulties that faced the nation was to take no stand at all on the issues that divided the North and the South.

With four candidates in the field, Lincoln received only 40% of the popular vote and 180 electoral votes — enough to narrowly win the crowded election. This meant that 60% of the voters had selected someone other than Lincoln. With the results tallied, the question was, would the South accept the outcome? A few weeks after the election, South Carolina seceded from the Union.

SECESSION

The force of events moved very quickly upon the election of Lincoln. South Carolina acted first, calling for a convention to secede from the Union. State by state, conventions were held, and the Confederacy was formed.

Within three months of Lincoln’s election, seven states had seceded from the Union. Just as Springfield, Illinois celebrated the election of its favorite son to the Presidency on November 7, so did Charleston, South Carolina, which did not cast a single vote for him. It knew that the election meant the formation of a new nation. In a reference to the protests against British rule in the 1770s, the Charleston Mercury wrote, “The tea has been thrown overboard, the revolution of 1860 has been initiated.” Secondary Source: Map

Secondary Source: Map

The United States and Confederate States of America in 1861.

Within a few days, the two United States Senators from South Carolina submitted their resignations. On December 20, 1860, by a vote of 169-0, the South Carolina legislature enacted an “ordinance” that “the union now subsisting between South Carolina and other States, under the name of ‘The United States of America,’ is hereby dissolved.” South Carolina’s action resulted in conventions in other Southern states. Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas all left the Union by February 1. On February 4, delegates from all these states except Texas met in Montgomery, Alabama, to create and staff a government called the Confederate States of America. They elected President Jefferson Davis. The gauntlet was thrown. How would the North respond?

A few last ditch efforts were made to end the crisis through Constitutional amendment. Senator James Henry Crittenden proposed to amend the Constitution to extend the old 36°30′ line to the Pacific. All territory north of the line would be forever free, and all territory south of the line would receive federal protection for slavery. Republicans refused to support the measure.

On March 2, 1861, two days before Lincoln’s inauguration, the 36th Congress passed the Corwin Amendment and submitted it to the states for ratification as an amendment to the Constitution. Senator William H. Seward of New York introduced the amendment in the Senate and Representative Thomas Corwin of Ohio introduced it in the House of Representatives. The text of the proposed amendment was:

“No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State.”

Like the rest of the language in the Constitution prior to the Civil War, the proposed amendment never uses the word “slavery,” instead employing the euphemisms “domestic institutions” and “persons held to labor or service.” The proposed amendment was designed to reassure the seceding slave states that the federal government would not interfere with their “peculiar institution.” If it had passed, it would have rendered unconstitutional any subsequent amendments restricting slavery, such as the 13th Amendment, which outlawed slavery throughout the nation. The Corwin Amendment passed the state legislatures in Ohio, Kentucky, Rhode Island and Maryland. Even Lincoln’s own state of Illinois passed it, though the lawmakers who voted for it in Illinois were not actually the elected legislators but were delegates to a state constitutional convention.

Lincoln supported the amendment, specifically mentioning it in his first inaugural address:

“I understand a proposed amendment to the Constitution — which amendment, however, I have not seen — has passed Congress, to the effect that the Federal Government shall never interfere with the domestic institutions of the States, including that of persons held to service … holding such a provision to now be implied constitutional law, I have no objection to its being made express and irrevocable.”

The amendment failed to get the required approval of 3/4 of all state legislatures for a constitutional amendment, largely because many of the Southern slave states had already seceded and did not vote on it.

What was the president doing during all this furor? Abraham Lincoln would not be inaugurated until March 4. James Buchanan presided over the exodus from the Union. Although he thought secession to be illegal, he found using the army in this case to be unconstitutional. Both regions awaited the arrival of President Lincoln and wondered anxiously what he would do.

LINCOLN’S FIRST INAUGURATION

Abraham Lincoln’s first inaugural address was delivered on Monday, March 4, 1861, as part of his taking of the oath of office for his first term as the sixteenth President of the United States. The speech was primarily addressed to the people of the South, and was intended to succinctly state Lincoln’s intended policies and desires.

Written in a spirit of reconciliation toward the seceded states, Lincoln’s inaugural address touched on several topics: first, his pledge to “hold, occupy, and possess the property and places belonging to the government”—including Fort Sumter in South Carolina, which was still in federal hands; second, his argument that the Union was undissolvable, and thus that secession was impossible; and third, a promise that while he would never be the first to attack, any use of armed force against the United States would be regarded as rebellion, and met with force.

Lincoln denounced secession as anarchy, and explained that majority rule had to be balanced by constitutional restraints in the American system of republicanism, saying, “A majority held in restraint by constitutional checks and limitations, and always changing easily with deliberate changes of popular opinions and sentiments, is the only true sovereign of a free people.”

Desperately wishing to avoid this terrible conflict, Lincoln ended with this impassioned plea:

“I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

While much of the Northern press praised or at least accepted Lincoln’s speech, the new Confederacy essentially met his inaugural address with contemptuous silence. The Charleston Mercury was an exception: it excoriated Lincoln’s address as manifesting “insolence” and “brutality,” and attacked the Union government as “a mobocratic empire.” The speech also did not impress other states who were considering secession from the Union. Indeed, after Fort Sumter was attacked and Lincoln declared a formal State of Insurrection, four more states—Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Arkansas—seceded from the Union and joined the Confederacy.

Modern writers and historians generally consider the speech to be a masterpiece and one of the finest presidential inaugural addresses, with the final lines having earned particularly lasting renown in American culture. Literary and political analysts likewise have praised the speech’s eloquent prose.

FORT SUMTER

It all began at Fort Sumter.

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina seceded from the Union. Five days later, 68 federal troops stationed in Charleston, South Carolina, withdrew to Fort Sumter, an island in Charleston Harbor. President Lincoln and the North considered the fort to be the property of the United States government. The people of South Carolina believed it belonged to the new Confederacy. Four months later, the first engagement of the Civil War took place on this disputed soil.

The commander at Fort Sumter, Major Robert Anderson, was a former slave owner who was nevertheless unquestionably loyal to the Union. With 6,000 South Carolina militia ringing the harbor, Anderson and his soldiers were cut off from reinforcements and resupplies. In January 1861, as one the last acts of his administration, President James Buchanan sent 200 soldiers and supplies on an unarmed merchant vessel, Star of the West, to reinforce Anderson. It quickly departed when South Carolina artillery started firing.

In February 1861, Jefferson Davis was inaugurated as the provisional president of the Confederate States of America, in Montgomery, Alabama. On March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln took his oath of office as president of the Union in Washington, DC. The fate of Fort Sumter lay in the hands of these two leaders.

As weeks passed, pressure grew for Lincoln to take some action on Fort Sumter and to reunite the states. Lincoln thought of the Southern secession as “artificial.” When Jefferson Davis sent a group of commissioners to Washington to negotiate for the transfer of Fort Sumter to South Carolina, they were promptly rebuffed.

Lincoln had a dilemma. Fort Sumter was running out of supplies, but an attack on the fort would appear as Northern aggression. States that still remained part of the Union (such as Virginia and North Carolina) might be driven into the secessionist camp. People at home and abroad might become sympathetic to the South. Yet Lincoln could not allow his troops to starve or surrender and risk showing considerable weakness.

At last he developed a plan. On April 6, Lincoln told the governor of South Carolina that he was going to send provisions to Fort Sumter. He would send no arms, troops, or ammunition — unless, of course, South Carolina attacked.

Now the dilemma sat with Jefferson Davis. Attacking Lincoln’s resupply brigade would make the South the aggressive party. But he simply could not allow the fort to be resupplied. J.G. Gilchrist, a Southern newspaper writer, warned, “Unless you sprinkle the blood in the face of the people of Alabama, they will be back in the old Union in less than ten days.”

Davis decided he had no choice but to order Major Anderson to surrender Sumter. Anderson refused.

The Civil War began at 4:30 a.m. on April 12, 1861, when Confederate artillery, under the command of General Pierre Gustave T. Beauregard, opened fire on Fort Sumter. Confederate batteries showered the fort with over 3,000 shells in a three-and-a-half day period. Anderson surrendered. Ironically, Beauregard had developed his military skills under Anderson’s instruction at West Point. It was the first of countless relationships and families devastated in the Civil War. The fight was on.

CONCLUSION

Clearly the problems of slavery and especially the expansion of slavery into the West were enormous, but there were efforts at compromise. If the influential voices of the day – John Brown, Charles Sumner or Preston Brooks for example – hadn’t been so extreme in their rhetoric or actions and had followed more closely the conciliatory example of Abraham Lincoln, could war have been avoided?

Or, had the problem just grown so large that war was inevitable, no matter how brilliant or charismatic the nation’s leaders might have been. By the end of the 1850s, could anyone have keep the peace?

What do you think? Could America’s leaders have prevented the Civil War?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: In the 1850s politicians tried but were unable to stop the increasingly divisive issue of slavery from leading to the outbreak of war between the slave states of the South and the free states of the North.

The Fugitive Slave Act required Northerners to help Southerners catch and return slaves trying to escape along the Underground Railroad. It was part of the Compromise of 1850. One slave, Dred Scott, went to court against his owner after having been brought to the North. He argued that because he was in a free state, he was free. The Supreme Court ruled in Dred Scott v. Sanford that he was not. This ruling effectively made slavery legal in all states and territories. It was terrifying for Northerners.

Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas held a series of famous debates in Illinois as they campaigned for the Senate. Lincoln lost the election, but the debates were republished widely since they were essentially a debate about the future of slavery. Douglas advocated for popular sovereignty. Lincoln argued that the nation could not survive half free and half slave. He predicted that it would become all one or all the other.

In Congress, politicians accused one another of inciting violence in Kansas, and fighting broke out on the floor of the Senate.

John Brown attacked the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry in an attempt to launch a general slavery uprising. His effort failed and he was captured, tried and executed for treason. In the process he became a martyr for the abolitionist cause. Northerners might have seen the Dred Scott case as evidence that slave power had taken over Washington, but Southerners believed John Brown’s raid showed that abolitionists were willing to ignore the law and use violence to take away their slaves.

In the election of 1860, Abraham Lincoln won as the first Republican president. He did not appear on the ballot in any southern state. Southerners viewed his victory as evidence that the North would do anything to get its way and that the less populous South would be the losers in the end.

Eleven southern states seceded and formed the Confederate States of America. Four slave states chose not to secede and remained in the Union. Lincoln took office hoping to keep the nation together, but warned the South that if they insisted on leaving, it would mean war. When Southerners bombed Fort Sumter in South Carolina, the Civil War began.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Charles Sumner: Senator from Massachusetts, abolitionist, and leader of the Radical Republicans who advocated for immediate abolition.

Constitutional Union Party: A political party that existed just before the start of the Civil War. They argued simply that the nation should stay together and ignore the question of slavery. They did not win, but their candidate John Bell won some votes in the election of 1860.

Dred Scott: A slave who sued for his freedom after being taken into the North. His case went all the way to the Supreme Court where he lost.

Jefferson Davis: President of the Confederacy. Usually regarded as an ineffective wartime leader.

Martyr: A hero who dies for a cause.

Preston Brooks: Senator from South Carolina who angrily beat Charles Sumner on the floor of the Senate with his cane. He became a hero in the South.

Robert E. Lee: Brilliant general from Virginia who led the assault on John Brown at Harper’s Ferry and later led the Confederate armies during the Civil War. His surrender to Ulysses S. Grant ended the war.

Roger Taney: The Supreme Court Chief Justice who wrote the Dred Scott decision.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

A House Divided: This was a metaphor that Abraham Lincoln articulated during the Lincoln-Douglas Debates. He said that the nation was like a house that could not stand if it was divided. He predicted that the country would either become all slave, or all free, but could not continue with slavery allowed in only the South.

Freeport Doctrine: Named for the town of Freeport, Illinois where Stephen Douglas articulated it in one of the Lincoln-Douglas Debates, the Freeport Doctrine was Douglas’s assertion that despite the Dred Scott decision, the people of new territories could still ban slavery on their own. His argument for popular sovereignty angered Democrats in the South and helped lead to a split in the party.

Popular Sovereignty: The idea that the residents of each territory should decide for themselves if they would join the Union as a free or slave state. Stephen Douglas supported this idea and it was the heart of the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

The Better Angels of our Nature: A famous image invoked by President Lincoln at his first inaugural address when he called upon the nation to avoid war.

![]()

COURT CASES

Dred Scott v. Sanford: A landmark Supreme Court case in 1857 in which Chief Justice Roger Taney wrote that the federal government did not have the power to regulate slavery, effectively allowing slavery in all states, North and South, as well as the territories. The outcome of the case infuriated abolitionists who saw it as a major expansion of the power of slave owners over the federal government.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Confederacy: The Confederate States of America – the slave-holding states from the South that seceded.

Fort Sumter: Fort in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. The Union controlled the fort at the start of the Civil War, and Confederate troops bombarded and took control of the fort. It was the first military action of the war.

Harper’s Ferry: A small town in West Virginia and site of the federal arsenal that John Brown attacked.

![]()

EVENTS

Lincoln-Douglas Debates: A series of famous debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas during their campaign for the open Illinois senate seat in 1858. Lincoln, a Republican, and Douglas a Democrat drew national attention as they debated the future of slavery. Despite losing the election, the debates catapulted Lincoln to widespread fame and respect.

![]()

LAWS

Fugitive Slave Act: A law passed by the United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern slave-holding interests and Northern Free-Soilers. The Act was one of the most controversial elements of the 1850 compromise and heightened Northern fears of a “slave power conspiracy” that was taking control of the federal government. It required that all escaped slaves were, upon capture, to be returned to their masters and that officials and citizens of free states had to cooperate in this law.

https://www.britannica.com/event/Fugitive-Slave-Acts (This link shows more details about the fugitive slave act and it’s impact in history)

What were the main reasons why Abraham Lincoln believed there would be no such thing as compromise in the decision of slavery?

How big of a role did railroads play in campaigning?

After the Civil War what kind of measures were taken to ensure that the states couldn’t secede from the Union and start a second Civil War? Why was the issue of states seceding never brought up before this time period?

I find it interesting that Lincoln is one of the most liked Presidents in modern time only got 40% of the popular vote.

In Charleston Mercury’s quote, “the tea has been thrown overboard, the revolution of 1860 has been initiated,” does it make the predicament that there would be a new formation of a new nation?

Why didn’t Texas join the other seceding states to form the Confederate States of America?

What happened to Dred Scott after he was denied by the court for freedom?

Why was Lincoln becoming president such a big turning point during the times of the Civil War?

What happened to Major Anderson?

What if Douglas became president? How would that change history?

If James Buchanan were to use the army instead of seeing it as unconstitutional, what would have happened?

Were there any Northern states that supported the Fugitive Slave Act?

Did the South consider any other factors besides for Douglas’s betrayal to them when the Election of 1860 was taking place? Yes he did betray them during John Brown’s Raid, but he was a supporter of slavery. Slavery was a big concept for the South so why didn’t they choose him? In my opinion, he would’ve been a strong advocate for slavery and would have done a better job at preserving slavery.

What did Lincoln mean in his first inaugural address when he stated “The Better Angels of our Nature?” I realize that he used it to call upon the nation to avoid war, however did he mean anything else besides that?

American leaders could not have prevented the Civil War because they were just merely speakers for both sides. What drove up to the Civil War was the people, Northerners, and the Southerners. These two groups had opposing views and never wanted to cooperate with each other. If one side seemed to have little more benefit, the other side would outrage. Since the two sides can’t be satisfied at the same time, the tension increased. Rebellion and violence from these people added to the tension. With the people fueled up, leaders have no choice but to voice their stance.

Could Lincoln have done more to prevent this Civil War, if not than how or who else could have prevented this?

Could states secede if they wanted to today, or are there laws that prohibit that?

The Supreme Court ruled unilateral secession unconstitutional in 1869 in the Texas v. White Supreme Court case. This article explains more about if a state can constitutionally secede. https://www.historians.org/teaching-and-learning/teaching-resources-for-historians/sixteen-months-to-sumter/newspaper-index/dubuque-herald/can-a-state-constitutionally-secede

I feel as if “A house divided against itself cannot stand” is able to be applied to our political situation right now. (especially how the election is on the 3rd) People are very polarized on important issues/ policies right now which may escalate to something more in the future, but I would say that if we are able to find some common ground, hopefully not like those many compromises in the 1800s that just kind of pushed back the civil war, the American people can become more united and make more progress as a country!

Since the Dred Scott Case was dominated by Southerners in Court with only two Republicans, the decision felt biased but what would have happened if the roles were reversed where more Northerners would have an influence in Court? How big of an impact would it have made on the Civil War?

Was Lincoln or Davis a better leader for their states? I mean, obviously it seems like Lincoln was better because the North had won against the South. Although, there were a lot more free states than there were slave states, and the war still lasted 4 years. Who do you think was better?

In one of the Lincoln & Douglas debates, Lincoln explained that he felt that blacks were entitled to the rights that were in the Declaration of Independence, such as “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” If the earlier leaders, such as the Founding Fathers, had taken action for the abolishment of slavery early on, do you think we would’ve avoided the Civil War? Or do you think it would’ve caused the Civil War to occur earlier, like in the late 1700s or early 1800s?

Did Lincoln’s position on slavery reflect his personal convictions about slavery or one that would best ensure winning the election?

It’s interesting to observe how our morals have changed throughout history. Equality is a pretty natural right that we believe everyone should have in the 21st century, however this idea was not common back in the day. It’s on how people thought that slavery was completely normal and acceptable and never questioned. It does make me think I wonder what other changes will occur with time. I wonder what people will think in a 100 years when they look back at our way of thinking now, and maybe there’s things we think now that will no longer be acceptable.

Did the South legally secede? Wasn’t it if a state wanted to take territory out of the USA, it would have to get approval from Congress, so technically their secession was illegal?

By legal terms there was no provision in the Constitution that prohibits a state from seceding from the union. So the confederate states did claim the right to secede, no state did claim to be seceding for that right. Also, it was later determined by the Supreme Courts that unilateral secession was unconstitutional. But here are some links that talk more in depth about the secession of the Southern states.

Link:3 https://www.ushistory.org/us/32e.asp