TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson betrayed his past as a strict constructionist of the Constitution and did something the Constitution did not specifically grant him the authority to do: he bought land. In fact, he doubled the size of the nation. The enormous purchase turned out to be one of the greatest bargains the United States ever got.

The Louisiana Territory was huge. Even looking at a map of the nation today, the land Jefferson purchased covers almost a third of the lower 48 states. Perhaps most incredibly, Jefferson and most White Americans at the time had almost no idea what they had just bought. Few Whites had ventured far beyond the Mississippi River. On some maps, the entire Great Plains were simply labeled the “Great American Desert.”

When Jefferson’s Corp of Discovery set off to find out just what the nation had purchased, their leaders Lewis and Clark had instructions from Jefferson to explore, map, record what they found, and form friendly relationships with the Native Americans in the territory. This was Jefferson’s dream: westward expansion based on peaceful coexistence and scientific curiosity.

While Jefferson himself, and Lewis and Clark, may have believed in these ideals, the rest of America’s story of westward expansion tells a strikingly different tale. Violent conflict, broken treaties, cultural misunderstanding, encroachment, and ultimately cultural annihilation are the norm. It is the Corp of Discovery’s peaceful journey to the Pacific Ocean and back which stands out as the anomaly.

Why is this? Why did the spread of White Americans from sea to shining sea have to be so violent and destructive? Why didn’t Jefferson’s ideal typify the westward movement?

THE LOUISIANA PURCHASE

As president, Thomas Jefferson realized his greatest triumph as chief executive in 1803 when the United States bought the Louisiana Territory from France for $15 million. It was a bargain price, considering the amount of land involved. Perhaps the greatest real estate deal in American history, the Louisiana Purchase greatly enhanced the Jeffersonian vision of the United States as an agrarian republic in which yeomen farmers worked the land. Jefferson also wanted to bolster trade in the West, seeing the port of New Orleans and the Mississippi River (then the western boundary of the United States) as crucial to American agricultural commerce. In his mind, farmers would send their produce down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, where it would be sold to European traders.

The purchase of Louisiana came about largely because of circumstances beyond Jefferson’s control, though he certainly recognized the implications of the transaction. Until 1801, Spain had controlled New Orleans and had given the United States the right of deposit, that is, the right to traffic goods in the port without paying customs duties. That year, however, the Spanish had ceded Louisiana, including the port of New Orleans, to France. In 1802, the United States lost its right to deposit goods duty-free in the port, causing outrage among many, some of whom called for war with France.

Jefferson instructed Robert Livingston, the American envoy to France, to secure access to New Orleans, sending James Monroe to France to add additional pressure. The timing proved advantageous. Because black slaves in the French colony of Haiti had successfully overthrown the brutal plantation regime, Napoleon could no longer hope to restore the empire lost with France’s defeat in the Seven Years War. His vision of Louisiana and the Mississippi Valley as the source for food for Haiti, the most profitable sugar island in the world, had failed. In need of funds to support his wars against France’s European neighbors, the emperor agreed to the sale in early 1803.

The Louisiana Purchase helped Jefferson win reelection in 1804 by a landslide. Of 176 electoral votes cast, all but 14 were in his favor. The great expansion of the United States did have its critics, however, especially Northerners who feared the addition of more slave states and a corresponding lack of representation of their interests in the North. And under a strict interpretation of the Constitution, it remained unclear whether the president had the power to add territory in this fashion. But the vast majority of citizens cheered the increase in the size of the republic. For slaveholders, new western lands would be a boon; for slaves, the Louisiana Purchase threatened to entrench their suffering further.

The Louisiana Territory held tremendous promise, but the true extent of the United States’ new territory remained unknown. No one knew precisely what lay to the west or how long it took to travel from the Mississippi to the Pacific. To head the expedition into the Louisiana territory, Jefferson appointed his friend and personal secretary, twenty-nine-year-old army captain Meriwether Lewis, who was instructed to form a Corps of Discovery. Lewis in turn selected William Clark, who had once been his commanding officer, to help him lead the group. Secondary Source: Map

Secondary Source: Map

The route of the Lewis and Clark Expedition from St. Louis to the Pacific Ocean

Jefferson wanted to improve the ability of American merchants to access the ports of China. Establishing a river route from St. Louis to the Pacific Ocean was crucial to capturing a portion of the fur trade that had proven so profitable to Great Britain. He also wanted to legitimize American claims to the land against rivals, such as Great Britain and Spain. Lewis and Clark were thus instructed to map the territory through which they would pass and to explore all tributaries of the Missouri River. This part of the expedition struck fear into Spanish officials, who believed that Lewis and Clark would encroach on New Mexico, the northern part of New Spain. Spain dispatched four unsuccessful expeditions from Santa Fe to intercept the explorers. Lewis and Clark also had directives to establish friendly relationships with tribes, introducing them to American trade goods and encouraging warring groups to make peace. Establishing an overland route to the Pacific would bolster American claims to the Pacific Northwest, first established in 1792 when Captain Robert Gray sailed his ship Columbia into the mouth of the river that now bears his vessel’s name and forms the present-day border between the states of Oregon and Washington. Finally, Jefferson, who had a keen interest in science and nature, ordered Lewis and Clark to take extensive notes on the geography, plant life, animals, and natural resources of the region into which they journeyed.

After spending the winter of 1803–1804 encamped at the mouth of the Missouri River while the men prepared for their expedition, the Corps set off in May 1804. Although the 33 frontiersmen, boatmen, and hunters took with them Alexander Mackenzie’s account of his explorations and the best maps they could find, they had no real understanding of the difficulties they would face. Fierce storms left them drenched and freezing. Enormous clouds of gnats and mosquitos swarmed about their heads as they made their way up the Missouri River. Along the way they encountered and killed and ate a variety of animals including elk, buffalo, and grizzly bears. One member of the expedition survived a rattlesnake bite. As the men collected minerals and specimens of plants and animals, the overly curious Lewis sampled minerals by tasting them and became seriously ill at one point. What they did not collect, they sketched and documented in the journals they kept. They also noted the customs of the Native Americans who controlled the land and attempted to establish peaceful relationships with them in order to ensure that future White settlement would not be impeded.

The corps spent their first winter in the wilderness, 1804–1805, in a Mandan village in what is now North Dakota. There they encountered a reminder of France’s former vast North American empire when they met a French fur trapper named Toussaint Charbonneau. When the corps left in the spring of 1805, Charbonneau accompanied them as a guide and interpreter, bringing his teenage Shoshone wife Sacagawea and their newborn son. Charbonneau knew the land better than the Americans, and Sacagawea proved invaluable in many ways, not least of which was that the presence of a young woman and her infant convinced many groups that the men were not a war party and meant no harm. Secondary Source: Currency

Secondary Source: Currency

The dollar coin bearing the likeness of Sacagawea and her baby.

The Corps set about making friends with native tribes while simultaneously attempting to assert American power over the territory. The Corps followed native custom by distributing gifts, including shirts, ribbons, and kettles, as a sign of goodwill. The explorers presented native leaders with medallions, many of which bore Jefferson’s image, and invited them to visit their new “ruler” in the East. These medallions or peace medals were meant to allow future explorers to identify friendly native groups. Not all efforts to assert American control went peacefully; some Indians rejected the explorers’ intrusion onto their land. An encounter with the Blackfoot turned hostile, for example, and members of the corps killed two Blackfoot men.

After spending eighteen long months travelling and nearly starving to death in the Bitterroot Mountains of Montana, the Corps of Discovery finally reached the Pacific Ocean in 1805 and spent the winter of 1805–1806 in Oregon. They arrived back in St. Louis later in 1806 having lost only one man, who had died of appendicitis. Upon their return, Meriwether Lewis was named governor of the Louisiana Territory. Unfortunately, he died only three years later in circumstances that are still disputed, before he could write a complete account of what the expedition had discovered.

Although the Corps of Discovery failed to find the coveted, but non-existent, all-water route to the Pacific Ocean, it nevertheless accomplished many of the goals Jefferson had set. The men traveled across the North American continent and established relationships with many tribes, paving the way for fur traders like John Jacob Astor who later established trading posts and solidified American claims to Oregon. Delegates of several tribes did go to Washington to meet the president. Hundreds of plant and animal specimens were collected, several of which were named for Lewis and Clark in recognition of their efforts. And the territory was more accurately mapped and legally claimed by the United States. Nonetheless, most of the vast territory, home to a variety of native peoples, remained unknown to Americans.

THE SIXTY YEARS WAR

History is usually thought of in stages, and American history is generally broken down in fairly predictable ways. Our own study of history has so far followed the traditional pattern. However, in studying the westward expansion of White American culture, and the corresponding loss of land and culture on the part of the Native population, it is worth looking at events and separating them into a different set of periods. In doing so, a new conflict emerges, albeit one that is not known outside of academic circles: The Sixty Years War.

The Sixty Years’ War from 1754 to 1814 was a military struggle for control of the Great Lakes and Mississippi River region, encompassing a number of wars over several generations. Traditionally, the war for control of the Great Lakes region has been written about only in reference to the individual wars. The designation Sixty Years’ War provides a framework for viewing this era as a continuous whole. The Sixty Years’ War encompassed multiple conflicts:

In the Seven Years War of 1754 to 1763, Native Americans generally fought alongside the French. The Iroquois Confederacy attempted to remain neutral in the conflict, except for the Mohawks, who fought as British allies. The conquest of New France by the British marked the end of French colonial power in the region and the establishment of British rule in what would become Canada. While the conflict between France and Great Britain ended in 1763, Pontiac’s Rebellion continued for another two years in which tribes that had been allies of the defeated French renewed the struggle against the British victors, eventually leading to a negotiated truce.

While the Proclamation of 1763 was intended to prevent conflicts between settlers and Natives on the western side of the Appalachian Mountains, it did not. A war with Ohio tribes, primarily Shawnees and Mingos, forcing them to cede their hunting ground south of the Ohio River in modern Kentucky, was fought in 1764.

The American Revolutionary War of 1775 to 1783 spilled over onto the frontier, with British commanders in Canada working with Native American allies to halt White expansion and to provide a strategic diversion from the primary battles in the East. With the victory of the United States in the war, Great Britain ceded the Old Northwest, the homeland of many of her Native allies, to the Americans.

Naturally, a large confederation of Native tribes resisted occupation of the Old Northwest. After suffering numerous defeats, the United States won the Battle of Fallen Timbers and gained control of most of modern Ohio. Fighting for control of territory continued and when the United States declared war on Great Britain in 1812, the British and Native tribes once again united in their common effort to defeat the United States.

The war between the United States and Great Britain Canada ended as a stalemate, establishing the Great Lakes as a permanent boundary between the United States and Canada. After this struggle, Native Americans in the region no longer had a European ally in the struggle against White expansion.

Since we have already studied the Seven Years War, the War for Independence and the War of 1812, we will not look again at those conflicts from the perspective of White Americans and Europeans, but rather look at the Native conflicts that occurred concurrently with the War of 1812.

TECUMSEH’S WAR

The Shawnee chief Tecumseh and American general William Henry Harrison had both been junior participants in the Battle of Fallen Timbers at the close of the American Revolution. Tecumseh was not among the signers of the Treaty of Greenville between the United States and Britain’s Native allies that had ended the war and ceded much of present-day Ohio, long inhabited by the Shawnees and other Native Americans, to the United States. However, many Indian leaders in the region accepted the Greenville terms, and for the next ten years, resistance to American power in Ohio faded.

Most of Ohio Shawnee and Miami who had participated in the earlier war and signed the Greenville Treaty urged cultural adaptation and accommodation with the United States. The tribes of the region participated in several treaties, including the Treaty of Grouseland and the Treaty of Vincennes, that gave and recognized American possession of most of southern Indiana. The treaties resulted in an easing of tensions by allowing settlers into Indiana and appeasing the Indians with reimbursement for lands lost.

In May 1805, Lenape Chief Buckongahelas, one of the most important native leaders in the region, died of either smallpox or influenza. The surrounding tribes believed his death was caused by a form of witchcraft, and a witch-hunt ensued, leading to the death of several suspected Lenape witches. The witch-hunts inspired a nativist religious revival led by Tecumseh’s brother Tenskwatawa, better known as The Prophet, who emerged in 1805 as a leader among the witch hunters. He posed a threat to the influence of the accommodationist chiefs, to whom Buckongahelas had belonged.

As part of his religious teachings, Tenskwatawa urged Natives to reject White American ways, such as drinking liquor, European-style clothing, and firearms. He also called for the tribes to refrain from ceding any more lands to the United States. Numerous leaders who preferred cooperation with the United States were accused of witchcraft and some were executed by followers of Tenskwatawa. The older, moderate leaders who had signed the Treaty of Greenville began to put pressure on Tenskwatawa and his followers to leave the area to prevent the situation from escalating.

Three years after starting their movement, Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh retreated further northwest and established the village of Prophetstown near the confluence of the Wabash and Tippecanoe Rivers, land claimed by the Miami. The Miami leader Little Turtle told the Shawnee that they were unwelcome there, but the warnings were ignored. Tenskwatawa’s religious teachings became more widely known as they became more militant, and he attracted Native American followers from many different nations, including Shawnee, Iroquois, Chickamauga, Meskwaki, Miami, Mingo, Ojibwe, Ottawa, Kickapoo, Delaware (Lenape), Mascouten, Potawatomi, Sauk, Tutelo and Wyandot. Tecumseh eventually emerged as the leader of the confederation, but it was built upon a foundation established by the religious appeal of his younger brother.

Prophetstown came to be the largest Native American community in the Great Lakes region and served as an important cultural and religious center. It was an intertribal, religious stronghold along the Wabash River in Indiana for 3,000 Native Americans; it was known as Prophetstown to whites. Led by Tenskwatawa initially, and later jointly with Tecumseh, thousands of Algonquin-speaking people gathered along the banks of the Tippecanoe River to gain spiritual strength. Primary Source: Painting

Primary Source: Painting

Tecumseh’s younger brother, Tenskwatawa, was painted by George Catlin in 1830, many years after he and his brother led the confederation of tribes at Prophetstown.

Meanwhile, in 1800, William Henry Harrison had become the governor of the newly formed Indiana Territory. Harrison sought to secure title to Native lands to allow for American expansion. In particular, he hoped that the Indiana Territory would attract enough White settlers to qualify for statehood.

In 1809, Harrison was able to negotiate among the various tribes in the territory for an agreement to sell lands. The Treaty of Fort Wayne was signed on September 30, 1809, in which the United States purchased over 4,600 square miles of Native land.

Tecumseh was outraged by the Treaty of Fort Wayne and revived an idea advocated in previous years by the Shawnee leader Blue Jacket and the Mohawk leader Joseph Brant that stated that Native land was owned in common by all tribes, and thus no land could be sold without agreement by all. Tecumseh knew that such broad consensus was nearly impossible to achieve.

Not yet ready to confront the United States directly, Tecumseh’s primary adversaries were initially the Native American leaders who had signed the treaty, and he threatened to kill them all. Tecumseh began to expand on his brother’s teachings that called for the tribes to return to their ancestral ways, and began to connect the teachings with the idea of a pan-tribal alliance. Tecumseh began to travel widely, urging warriors to abandon the accommodationist chiefs and to join the resistance at Prophetstown.

Harrison was impressed by Tecumseh and even referred to him in one letter as “one of those uncommon geniuses.” He feared Tecumseh had the potential to create a strong empire if he went unchecked and suspected that he was behind attempts to start an uprising. Harrison also feared that if Tecumseh were able to achieve a truly pan-tribal federation, the British would take advantage of the situation and ally with the Natives in an effort to retake the Great Lakes region.

In August 1810, Tecumseh and 400 armed warriors traveled down the Wabash River to meet with Harrison in Vincennes. The warriors were all wearing war paint, and their sudden appearance at first frightened the soldiers. The leaders of the group were escorted to Grouseland, where they met Harrison. Tecumseh insisted that the Fort Wayne treaty was illegitimate and asked Harrison to nullify. He warned that Americans should not attempt to settle the lands sold in the treaty. Tecumseh acknowledged to Harrison that he had threatened to kill the chiefs who signed the treaty if they carried out its terms, and that his confederation was rapidly growing. Harrison rejected Tecumseh’s claim that all the Indians formed one nation, and each nation could have separate relations with the United States.

Tecumseh launched an impassioned rebuttal, but Harrison was unable to understand his language. A Shawnee who was friendly to Harrison cocked his pistol from the sidelines to alert Harrison that Tecumseh’s speech was leading to trouble. Finally, an army lieutenant who could speak Tecumseh’s language warned Harrison that he was encouraging the warriors with him to kill Harrison. Many of the warriors began to pull their weapons and Harrison pulled his sword. The entire town’s population was only 1,000 and Tecumseh’s men could have easily massacred the town, but once the few officers pulled their guns to defend Harrison, the warriors backed down. Chief Winnemac, who was friendly to Harrison, countered Tecumseh’s arguments to the warriors and instructed them that because they had come in peace, they should return in peace and fight another day. Before leaving, Tecumseh informed Harrison that unless the treaty was nullified, he would seek an alliance with the British.

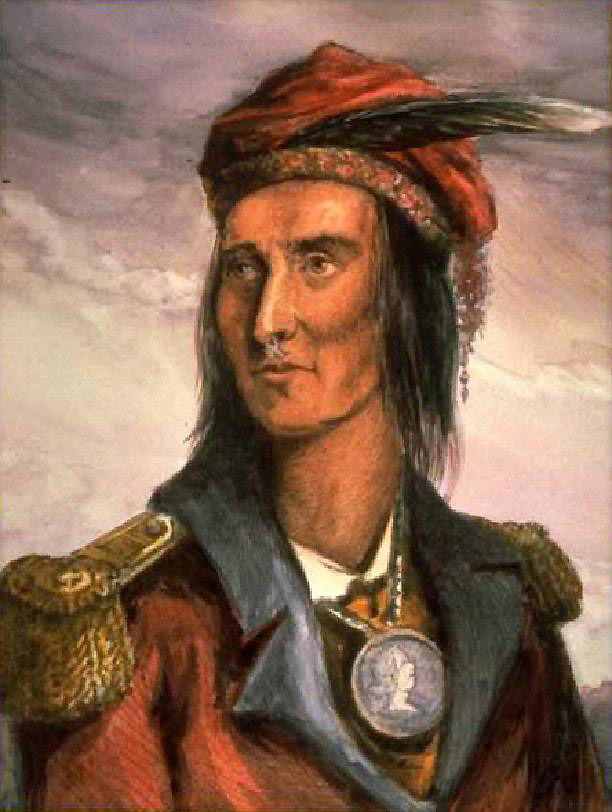

During the next year, tensions escalated. Four settlers were murdered on the Missouri River, and in another incident, a boatload of supplies was seized by Natives from a group of traders. Harrison summoned Tecumseh to Vincennes to explain the actions of his allies. In August 1811, Tecumseh met with Harrison at Vincennes, assuring him that the Shawnee brothers meant to remain at peace with the United States. He then traveled to the South on a mission to recruit allies among the Cherokee, Creek, Choctow and other major tribes in the lower Mississippi. Most of the southern nations rejected his appeals, but a faction among the Creeks, who came to be known as the Red Sticks, answered his call to arms. Secondary Source: Painting

Secondary Source: Painting

This painting was created based on drawings of Tecumseh from his lifetime. Interestingly he wears a mix of both traditional and European clothing, including a medal received as a sign of friendship.

Having heard from intelligence that Tecumseh was far away, Governor Harrison decided to take advantage of the situation and embarked on a publicity campaign aimed at discrediting Tenskwatawa. Tecumseh ordered his brother to take no action, but The Prophet lifted the ban on firearms and was able to quickly procure them in large quantities from the British in Canada. Tenskwatawa took his brother’s absence as an opportunity to raise tensions even higher by further stirring up his followers.

While Tecumseh was still in the South, Harrison marched more than 1,000 men on an expedition to intimidate the Prophet and his followers. His stated goal was to force them to accept peace, but he acknowledged that he would launch a pre-emptive attack on the Natives if they refused. On November 6, 1811, Harrison’s army arrived outside Prophetstown, and Tenskwatawa agreed to meet Harrison in a conference to be held the next day. Tenskwatawa, perhaps suspecting that Harrison intended to attack the village, decided to risk a pre-emptive strike, sending out roughly 500 of his warriors against the American encampment. Before the dawn of the next day, the Indians attacked, but Harrison’s men held their ground, and the Natives withdrew from the village after the battle. Despite the surprise attack, the victorious Americans burned Prophetstown the following day. The Battle of Tippecanoe, as it is called today, was a short, but consequential conflict.

Harrison, and many subsequent historians, claimed that the Battle of Tippecanoe was a deathblow to Tecumseh’s confederacy. Harrison eventually became the President of the United States largely on the memory of this victory. The battle was a severe blow for Tenskwatawa, who lost prestige and the confidence of his brother.

By December, most of the major American newspapers began to carry stories on the battle. Public outrage grew and many Americans blamed the British for inciting the tribes to violence and supplying them with firearms. Andrew Jackson was among the forefront of men calling for war, claiming that Indians were “excited by secret British agents.” Other western governors called for action. William Blount of Tennessee called on the government to “purge the camps of Indians of every Englishmen to be found…” Acting on popular sentiment, Congress passed resolutions condemning the British for interfering in American domestic affairs. Tippecanoe fueled the worsening tension with Britain, helping to push reluctant Americans into the War of 1812.

In that war, Tecumseh found British allies in Canada. Canadians would subsequently remember Tecumseh as a defender of Canada, but his actions in the War of 1812, which would cost him his life, were a continuation of his efforts to secure Native American independence from outside dominance. Tecumseh and his efforts to unify Native Americans in the Great Lakes Region died along with him in the 1813 Battle of Thames.

THE CREEK WAR

The Creek War of 1813–1814, also known as the Red Stick War, began as a civil war within the Creek Nation, a powerful tribe located in the lower Mississippi region centered in what is now Alabama.

A faction of younger men from the Upper Creek villages, known as Red Sticks, sought aggressively to return their society to a traditional way of life, culturally and religiously. Red Stick leaders such as William Weatherford (Red Eagle), Peter McQueen, and Menawa were all allies of the British. They clashed violently with other Creek leaders over White American territorial encroachment. Many of the Upper Creek were influenced by the prophecies of Tecumseh’s brother, Tenskwatawa, which, echoing those of their own spiritual leaders, predicted the extermination of the European Americans.

The Red Sticks aggressively resisted the civilization programs administered by the government Indian Agent, Benjamin Hawkins, who had stronger alliances among the Lower Creek. Lower Creek towns had been under more pressure from settlers in present-day Georgia and had been persuaded to cede land in 1790, 1802, and 1805. Settlers had ruined hunting grounds, and as the wild game disappeared, the Lower Creek began adopting White farming practices.

In February of 1813, a small war party of Red Sticks, returning from Detroit and led by Little Warrior, killed two families of settlers along the Ohio River. Benjamin Hawkins learned of this, and demanded that the Creek turn over Little Warrior and his six companions to the government. Instead of complying, old Creek chiefs, led by Big Warrior, decided to execute the war party themselves. This decision ignited civil war in the Creek Nation. In the months that followed, warriors of Tecumseh’s party began to attack the property of their Lower Creek enemies, burning plantations and destroying livestock.

The first clashes between the Red Sticks and United States forces occurred on July 21, 1813. A group of territorial militia intercepted a party of Red Sticks returning from Spanish Florida, where they had acquired arms from the Spanish governor at Pensacola. The Red Sticks escaped and the soldiers looted what they found. Seeing the Americans looting, the Creek regrouped and attacked and defeated the Americans. The Battle of Burnt Corn, as the exchange became known, broadened the Creek Civil War to include American forces.

Concerned about the ongoing conflict, the Tennessee legislature authorized Governor Willie Blount to raise 5,000 militia for a three-month tour of duty to make war on the Red Stick Confederacy. Blount called out a force of 2,500 West Tennessee men under Colonel Andrew Jackson to “repel an approaching invasion… and to afford aid and relief to… Mississippi Territory.”

In addition to the state actions, the federal government sent emissaries to organize the friendly Lower Creek under Major William McIntosh, a Native chief, to aid the militias in actions against the Red Sticks. At the request of Return J. Meigs, the Cherokee Nation voted to join the Americans in their fight against the Red Sticks. Under the command of Chief Major Ridge, 200 Cherokee fought with the Tennessee Militia under Colonel Andrew Jackson. The irony of Cherokee warriors fighting under Jackson’s command against other Native Americans should not be lost on anyone.

The Red Stick Confederacy was unprepared for the scope of the conflict they had brought about. At most, their force consisted of 4,000 warriors, possessing perhaps 1,000 muskets. They had never been involved in a large-scale war, not even against neighboring tribes. Many Creek tried to remain friendly to the United States, but as the conflict progressed, few Whites in the region distinguished between friendly and unfriendly Creeks. Primary Source: Painting

Primary Source: Painting

Menawa, one of the leaders of the Red Sticks was painted in 1837 by Charles Bird King.

The war ended after Jackson commanded a force of combined state militias, Lower Creek, and Cherokee to defeat the Red Sticks at Horseshoe Bend along the Tallapoosa River in Alabama. The Battle of Horseshoe Bend, which occurred on March 27, 1814, was a decisive victory for Jackson, effectively ending the Red Stick resistance. On August 9, 1814, Andrew Jackson forced headmen of both the Upper and Lower Towns of Creek to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson. Despite protests from the Creek chiefs who had fought alongside Jackson, the Creek Nation was forced to cede 23 million acres of land, accounting for half of Alabama and part of southern Georgia, to the United States government. In what would be a prelude to his latter attitudes toward Native Americans, Jackson recognized no difference between his Lower Creek allies and the Red Sticks who fought against him, forcing both to cede their land.

SETTLEMENT OF THE MIDWEST

With land in the Midwest opened for White settlement through both treaty and by force, and the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, settlers from New England and the Middle Colonies spread throughout the region. Most of them started as farmers, but later the larger proportion moved to towns and cities as entrepreneurs and urban professionals.

The fact that most of the settlers in the Midwest were from the North had a lasting impact on the region. Historian John Bunker explained the effect in this way. “Because they arrived first and had a strong sense of community and mission, Yankees were able to transplant New England institutions, values, and mores, altered only by the conditions of frontier life. They established a public culture that emphasized the work ethic, the sanctity of private property, individual responsibility, faith in residential and social mobility, practicality, piety, public order and decorum, reverence for public education, activists, honest, and frugal government…” Social institutions in the Midwest tended toward communal involvement. A strong public school system was established and later immigrants from the Netherlands and Scandinavia found both the climate and the philosophical outlook of the Midwest inviting and familiar.

In contrast, territories to the south, including Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama and Mississippi became home to slave-owning planters who transported their hierarchical culture and slave-based economy. Also making the journey were thousands of descendants of the Scotch-Irish, who formed the lower class of White non-slave-owning residents of the trans-Appalachian South.

CONCLUSION

When English settlers first landed in New England and Virginia, leaders such as Powhattan and Massasoit attempted to forge positive trading and defensive alliances with the Whites, but found that land ownership was an issue on which their new neighbors simply had no willingness to compromise. As the decades wore on, generation after generation of Native Americans did their best to protect their lands from the advance of English-speaking settlers. They partnered with the French in 1754, with the British in 1775, and with the British again in 1812. While some had tried peaceful negotiation that resulted in sales of land, and others had even adopted the lifestyles of the Whites even so far as to use the American court system, the ultimate outcome was the same. Like all their forbearers, Tecumseh and his followers, the Creeks, the Cherokee, and the many tribes whose traditional homelands were east of the Mississippi River, found that there was little they could do to prevent White encroachment on their territory.

Jefferson knew that White culture was going to spread west, and did nothing to hide his desire that it would. But he did not envision the violent, tragic struggles that typified the movement. Why wasn’t his vision of expansion based on respect, understanding, peaceful cooperation, and scientific curiosity the norm?

Was the opportunity for peace betrayed by greedy settlers, or impatient young Native Americans? Was the timing always just a little wrong? In the Spanish colonies Native Americans intermarried with Europeans and the cultures became a blend of both worlds. But this didn’t happen in the United States. Why not?

What do you think? Did the settlement of the West by Whites have to be violent?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: Native Americans had been fighting White expansion for many years. Their primary goal was preserving their land which was the principal factor in their decisions about who to side with in the Seven Years War, American Revolution, War of 1812, and in their own conflicts with White Americans.

Thomas Jefferson purchased Louisiana from France in 1803. The land he bought was much larger than the current State of Louisiana. In effect, Jefferson doubled the size of the country. To explore the land he had just purchased, he sent Lewis and Clark on a multi-year journey to the Pacific Ocean and back. Their Corps of Discovery was meant to map the land, study the animals and plants, and make friendly connections to the Native Americans. They were helped by Sacagawea, a young mother who helped translate along the way.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition may have been peaceful, but most encounters between White Americans and Native Americans were not. Natives had been fighting for 60 years to try to preserve their lands, and they mostly were losing. They had fought in the Seven Years War, the Revolution and during the War of 1812.

Between the Revolution and the War of 1812, Tecumseh and his brother “The Prophet” Tenskwatawa had tried to unite the tribes along the Mississippi River to form a wall against White expansion. They ended up fighting American troops at the Battle of Tippecanoe led by William Henry Harrison and lost. Tecumseh left for Canada, Harrison became popular and won the presidency, and White expansion continued.

Much of this fighting took place in the region we now call the Midwest, encompassing the states of Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Ohio and Wisconsin. Once Native Americans had been defeated and the Erie Canal opened, White settlers from New England, New York and Pennsylvania swarmed in. They all became states before the Civil War.

Creeks in the South also fought White advancement into their territory at the same time as the War of 1812. Like William Henry Harrison, Andrew Jackson fought them, won and later won the presidency as well.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Meriwether Lewis: Along with Clark, one of the two leaders of the Corps of Discovery that President Jefferson sent to explore the Louisiana Purchase.

William Clark: Along with Lewis, one of the two leaders of the Corps of Discovery that President Jefferson sent to explore the Louisiana Purchase.

Corps of Discovery: Group of explorers led by Lewis and Clark that crossed the new Louisiana Purchase all the way to the Pacific Ocean. They tried to establish peaceful relationships with Native Americans, created maps, and recorded the plants and animals they found.

Sacagawea: Native American woman who travelled with Lewis and Clark during their exploration of the Louisiana Purchase. Her services as an interpreter were invaluable.

Tecumseh: Native American political leader who, along with his brother The Prophet, organized a campaign to unite the tribes up and down the Mississippi River against White expansion during the early 1800s. His army was defeated at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811 and he moved to Canada.

Tenskwatawa: Also known as The Prophet, he was the brother of Tecumseh and provided a spiritual rationale for resistance to White expansion. He was less talented as a military leader than his brother and his mistakes helped lead to their defeat at Tippecanoe in 1811.

William Henry Harrison: Governor of Indiana who defeated Tecumseh’s army in the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811. He capitalized on his popularity as an “Indian fighter” to win the presidency in 1840 but died after only 31 days in office.

Red Sticks: Group of Creek Native Americans who had been allied with the British during the War of 1812 and were supporters of Tecumseh. They wanted to use violence to resist White expansion and fought with other members of the Creek Nation in what became known as the Creek War.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Prophetstown: Tecumseh’s camp in Indiana that was the site of the Battle of Tippecanoe.

![]()

EVENTS

Battle of Tippecanoe: 1811 fight between American troops led by Indiana governor William Henry Harrison and a coalition of Native Americans led by Tecumseh. Harrison was victorious, thus breaking the last major coordinated effort to stop White expansion east of the Mississippi River.

Creek War: A series of conflicts in 1813 and 1814 between members of the Creek Nation in what is now Alabama. The conflict was about how best to deal with White expansion – accommodation or violent resistance.

Battle of Horseshoe Bend: Decisive battle in 1814 between American forces under the command of Andrew Jackson and Red Stick Creeks. It resulted in the Treaty of Fort Jackson in which the Creek Nation agreed to give up their land.

![]()

TREATIES, LAWS & POLICIES

Louisiana Purchase: 1803 purchase of land from France by President Jefferson which doubled the size of the nation. It was an example of a loose interpretation of the Constitution despite Jefferson’s preference for strict interpretation.

Treaty of Greenville: 1795 agreement between Native American leaders in what is now Ohio and the American government in which the Native tribes agreed to give up their land. Tecumseh was among the minority of tribal leaders in Ohio who rejected the treaty and decided to fight White expansion.

Treaty of Fort Jackson: 1814 agreement between the Creek Nation and American government in which the Creeks agreed to give up their land and move west. It was a result of Andrew Jackson’s successful military campaign against the Red Stick Creeks.

https://www.nps.gov/articles/behind-the-sharp-knife.htm

“This source gives more information about Red Sticks and the Battle of Horseshoe Bend.”

Did the Native Americans ever use the Erie Canal or railroads or were they pushed out before they were built in that area?

If the Lousiana purchase was such a good deal I wonder why France was willing to sell all that land.

What if Jackson thought the Lower Creeks and Cherokees would support the British anyway, which is why he perceived no difference between the red sticks and lower creeks?

Who were the Yankees from the North, settling in the Midwest?

I notice how Texas still has the same Mexican community as it did when they won their independence from New Spain

If Jackson were not to take away their allies’ land during the war, would the relationship between Americans and Native Americans be different?

What happened to Tenskwatawa after Tecumseh died?

Why did Jackson take land from the lower creeks, when they helped defeat the Red Stick?

Who wrote/came up with the Treaty of Fort Wayne?

What did Jefferson feel about the whole situation between the Americans and the Creeks?

I find it really messed up that Jackson made Lower Creek give up land when they helped the Red Sticks with him and they had to give up the same thing.

Did the Lower Creek really trust Jackson to help protect their lands or did they just not want to loose against Upper Creek?

If Jackson couldn’t see the difference between his Lower Creek allies and the Red Sticks who he was fighting against, how did he treat his allies while he was fighting with them? Did the rest of the people involved in the treaty feel the same way as him?

What if we didn’t purchase Louisiana? Would we have claimed it by force later in history?

What made other Native American leaders sign the Treaty of Greenville?

Why didn’t the whites kick out the Native Americans for their land? Was it due to them having strength in numbers?

Despite Tecumseh’s passionate rebuttal concerning the Fort Wayne treaty, Harrison was unable to understand Tecumseh’s language. It is later mentioned that an army lieutenant understood Tecumseh’s language and warned Harrison that Tecumseh was encouraging the warriors to kill Harrison with him. If the army lieutenant understood Tecumseh’s language, why did he not translate Tecumseh’s rebuttal to Harrison?

Had the White expansion not been rebelled, what would be the difference if it hadn’t? I believe that the White settlers would have tried to kick the Native Americans out of their own territory since they did have more advanced weapons than the Natives. I say “tried” because I don’t think they would have been successful due to strong leadership by Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa and the disadvantage of being outnumbered by the Native Americans.

It said that Lewis had died before he could write a complete account of what the expedition had discovered, did Clark or anyone from the Corps take over to finish writing their discoveries?

When the whites were to force the natives out, what would happen to the rest of the tribes if they were to sign the treaties? Where would they go off to if the land that they occupied was to be bought and taken over for the expansion?

What kind of consequences did the Prophetstown encounter from Little Turtle since they were established on Miami land?

On the Lewis and Clark journey there were fierce storms that left them drenched and freezing, were there any people on that expedition that ended up getting sick from those storms and passing?

What made Sacagewa more important that she was put on the dollar coin ? Didn’t her and husband do the same thing ?

Sacagawea and her baby’s presence let tribes know that the men she was with weren’t going to do them any harm.

A pattern I’ve seen many times during early America is that many (if not all) presidents were proclaimed “war heroes” or played a substantial role in a battle/war. (ex: Harrison and Battle of Tippecanoe, Washington being a military commander) Nowadays though, presidents are not usually “war heroes” and presidents like Trump didn’t previously serve in a war.

How did American feel about expanding westward? and did the expansion affect slavery in the United States?

I think Americans were eager to expand Westward and that dated back to the French and Indian War were they expected the chance to move to the West, but the Proclamation of 1763 prevented them from doing that. For slavery I’m not really sure, but I think the movement of slavery to the West is dependent on the people. If it was people from the South there would probably be slavery and if it was the North I don’t there would be.

What made Tenskwatawa so inspiring to other leaders? Was it because of his brother? Was it because of his clash with Harrison?

Despite the Creek helping Colonel Andrew Jackson and other soldiers to defeat the Red Sticks, they were still forced to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson & give up 23 million acres of land to the government. Was this always Colonel Andrew Jackson’s plan from the very beginning? What did Jackson mean when he said he “recognized no difference” between his Lower Creek allies and the Red Sticks? Why did he think that way?

Where did the natives go after they signed the treaty of fort Jackson? Did some stay there?

It seems that throughout time Native Americans were getting outnumbered more and more. Did they ever stand a chance to protect their land or is it inevitable that they would lose it? In hindsight, are there any techniques/strategies they could’ve used to better protect themselves and what would those strategies be?

What did the Native American gain and lose, allying with Great Britain many times? Was Native Americans allying with foreign nation beneficial on their part? Would they be better off not allying with the foreign nations?

Despite being a believer of a strict interpretation, why did Jefferson go on his way to purchase the Louisiana territory? What made it so worth it that he had to violate this belief?

https://www.history.com/topics/westward-expansion/louisiana-purchase , this may help you get a better understanding on the reasoning behind Jefferson’s purchase of the Louisiana Territory. As a strict interpreter of the constitution, Jefferson also had the vision of America being an agrarian republic, and he also had a goal of boosting trade in the West. If he made the purchase he would satisfy both his goal and vision, because he saw the success that France had with the port of New Orleans and the Mississippi River and believed that these ports would be crucial for agricultural commerce.