TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

Historian John Meacham titled his acclaimed biography of Andrew Jackson “American Lion.” Indeed, Jackson was like a lion. He was fierce, determined in a political fight and unrelenting in pursuing his goals. He dominated over all other politicians in his time. He reshaped the presidency and Americans’ view of the relationship between politicians, voters and economic power.

From a modern perspective, Jackson’s achievements are equally his failures. He cleared land in the South for White settlers, but did so by illegally evicting entire nations of Native Americans. He destroyed the Second Bank of the United States in order to limit the power of elite Eastern bankers and in doing brought about an economic crisis that harmed both rich and poor. He successfully defeated a threat by southern leaders to secede and held the Union together and at the same time caused those leaders to be ever more determined to protect slavery as an economic system.

Second only to Washington, Jackson was the most influential president before the Civil War. Like Washington, he shaped the job, and like Washington he inspired a cult of personality. Also like Washington, he shaped a political party since, as much as Washington guided Federalist ideas in government, Jackson brought the ideas of the new Democratic Party to the capital.

Certainly in a list of all presidents based on their impact on American history, Jackson could place in the top 10, possibly the top 5. But is importance a qualifier for inclusion on our currency? Jackson first appeared on the $20 bill in 1928 when he replaced Grover Cleveland. As the centennial of women’s suffrage approached in the 2010s, a campaign to replace Jackson with a woman was launched and, in a poll, Harriet Tubman won out over Eleanor Roosevelt and Rosa Parks as the favored candidate. However, when Donald Trump succeeded Barack Obama as president, plans to redesign the $20 banknote were put on hold and Jackson retained his spot.

Regardless of who might replace him, does Jackson belong on our money?

JACKSON UPENDS WASHINGTON

After his election, Jackson removed almost 50% of appointed civil officers, which allowed him to handpick their replacements. This replacement of appointed federal officials is common today. Each new president appoints well over 1,000 supporters to top positions across the government. Under Jackson, this process happened for the first time. Lucrative posts, such as postmaster and deputy postmaster, went to party loyalists, especially in places where Jackson’s support had been weakest, such as New England. Some Democratic newspaper editors who had supported Jackson during the campaign also gained public jobs. Jackson’s opponents were angered and took to calling the practice the spoils system.

The rewarding of party loyalists with government jobs resulted in spectacular instances of corruption. Perhaps the most notorious occurred in New York City, where a Jackson appointee made off with over $1 million. Such examples seemed proof positive that the Democrats were disregarding merit, education, and respectability in decisions about the governing of the nation.

In addition to dealing with rancor over implementation of the spoils system, the Jackson administration became embroiled in a personal scandal known as the Petticoat Affair. This incident exacerbated the division between the president’s team and the insider class in the nation’s capital, who found the new arrivals from Tennessee lacking in decorum and propriety. At the center of the storm was Margaret “Peggy” O’Neal, a well-known socialite in Washington. O’Neal cut a striking figure and had connections to the republic’s most powerful men. She married John Timberlake, a naval officer, and they had three children. Rumors abounded, however, about her involvement with John Eaton, a senator from Tennessee who had come to Washington in 1818. Timberlake committed suicide in 1828, setting off a flurry of rumors that he had been distraught over his wife’s reputed infidelities. Eaton and Mrs. Timberlake married soon after, with the full approval of President Jackson.

The so-called Petticoat Affair divided Washington society. Many Washington socialites snubbed the new Mrs. Eaton as a woman of low moral character. Among those who would have nothing to do with her was Vice President John C. Calhoun’s wife, Floride. Jackson defended Peggy Eaton and derided those who would not socialize with her, declaring she was “as chaste as a virgin.” Jackson had personal reasons for defending Eaton. He drew a parallel between Eaton’s treatment and that of his late wife Rachel.

Although Jackson and John Quincy Adams removed themselves from the mudslinging of 1828, their parties waged a dirty campaign. Jackson’s wife, Rachel Donelson, became the target of vicious attacks. She had been unhappily married and moved away with Jackson thinking her first husband had secured a divorce. They found out two years later that the divorce had never been finalized. Although she divorced her former husband and remarried Jackson, his opponents labeling her an adulteress. Shortly after the campaign and just before he took the oath of office Rachel passed away. Understandably, Jackson blamed his political enemies for her death.

Martin Van Buren, who defended both Jackson and the Eatons organized social gatherings with them, became close to Jackson, who came to rely on a group of informal advisers that included Van Buren and was dubbed the Kitchen Cabinet. This select group of presidential supporters highlights the importance of party loyalty to Jackson and the Democratic Party. Primary Source: Cigar Box Cover

Primary Source: Cigar Box Cover

An artist’s design of a cigar box exploits Peggy Eaton’s fame and beauty, showing President Jackson introduced to Peggy O’Neal on the left and two lovers fighting a duel over her on the right.

THE NULLIFICATION CRISIS

By the late 1820s, the North was becoming increasingly industrialized, and the South was remaining predominately agricultural.

In 1828, Congress passed a high protective tariff as part of Henry Clay’s American System. The tariff infuriated the southern states because they felt it only benefited the industrialized North. For example, a high tariff on imports increased the cost of British textiles. This tariff benefited American producers of cloth, mostly in the North. However, it shrunk English demand for raw cotton from the South and increased the final cost of finished goods for American buyers. The Southerners looked to Vice President John C. Calhoun from South Carolina for leadership against what they labeled the Tariff of Abominations.

Calhoun had supported the Tariff of 1816, but he realized that if he were to have a political future in South Carolina, he would need to rethink his position. Some felt that this issue was reason enough for dissolution of the Union. Calhoun argued for a less drastic solution, the doctrine of nullification. According to Calhoun, the federal government only existed at the will of the states. Therefore, if a state found a federal law unconstitutional and detrimental to its interests, it would have the right to nullify that law within its borders. Calhoun advanced the position that a state could declare a national law void. This idea was not entirely new. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison had promoted this line of reasoning in 1798 and 1799 in their Virginia and Kentucky Resolves when they disagreed with the Federalist congress’s Alien and Sedition Acts.

The South Carolina Ordinance of Nullification was enacted into law on November 24, 1832 by the South Carolina legislature. As far as South Carolina was concerned, there was no tariff. A line had been drawn. Would President Jackson dare to cross it?

Jackson rightly regarded this states-rights challenge as so serious that he asked Congress to enact legislation permitting him to use federal troops to enforce federal laws in the face of nullification. Fortunately, an armed confrontation was avoided when Congress, led by the efforts of Henry Clay, revised the tariff with a compromise bill. This permitted the South Carolinians to back down without losing face. In retrospect, Jackson’s strong, decisive support for the Union was one of the great moments of his Presidency. If nullification had been successful, could secession have been far behind? Perhaps not, since any state would have been free to nullify any federal law they disagreed with. Nullification undermined the doctrine of federal authority established in the Gibbons v. Ogden decision by the Marshall Court and would have driven the nation back to the days of the Articles of Confederation when states, not the federal government, reigned supreme.

THE BANK WAR

The Second Bank of the United States was chartered in 1816 for a term of 20 years. The time limitation reflected the concerns of many in Congress about the concentration of financial power in a private corporation. The Bank was a depository for federal funds and paid national debts, but it was answerable only to its directors and stockholders and not to the electorate.

The supporters of a central bank were the same as those who had supported Alexander Hamilton’s first bank in the 1790s. They were involved in industrial and commercial ventures and wanted a strong currency and central control of the economy. The opponents, principally agrarians, were distrustful of the federal government. The critical question in the 1830s was, with whom would President Jackson side?

At the time Jackson became President in 1828, the Bank of the United States was ably run by Nicholas Biddle, a Philadelphian. Biddle was an astute businessman but not an adept politician. His underestimation of the power of a strong and popular President caused his downfall and the demise of the financial institution he commanded. Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

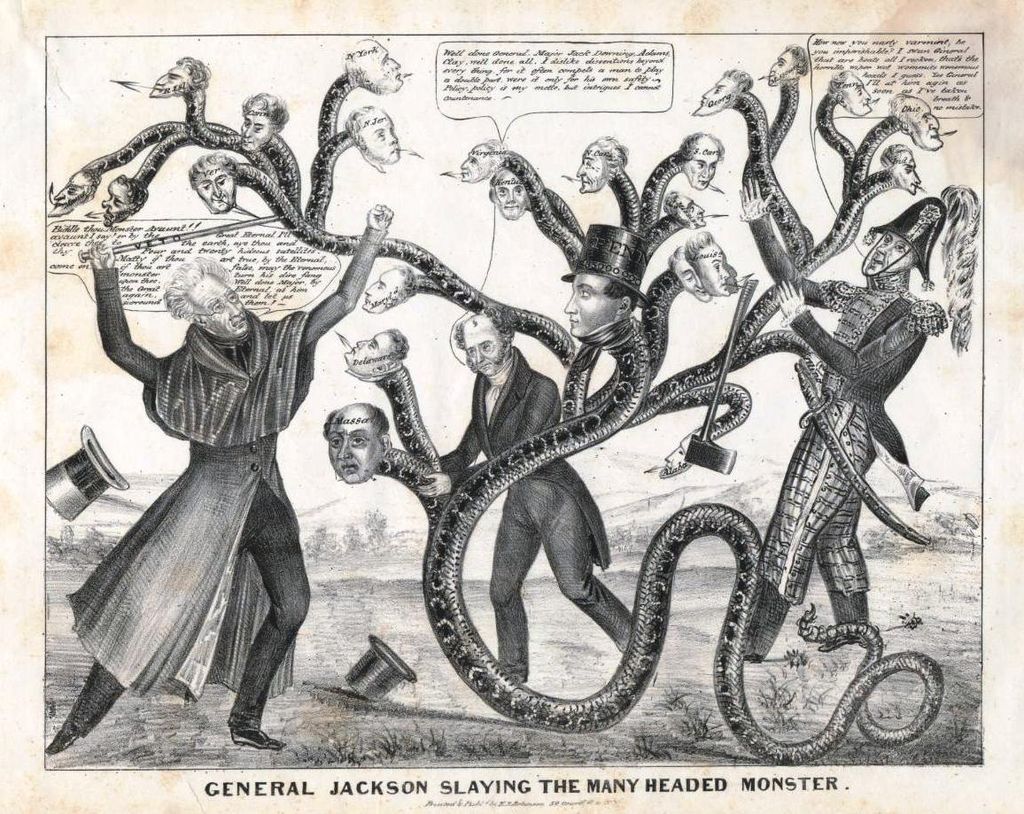

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

This pro-Jackson cartoon depicts him slaying the many headed monster of the moneyed interests of the Eastern elite.

Jackson had been financially damaged by speculation earlier in his life and would seem to be a natural supporter of the bank. However, he distrusted elitist eastern institutions. Furthermore, his supporters in the West wanted access to easy funding that would be produced by banks that could print their own currency.

In January 1832, Biddle’s supporters in Congress, principally Daniel Webster and Henry Clay, introduced Bank recharter legislation. Even though the charter was not due to expire for four more years, they felt that the members of the current Congress would recharter the Bank and that Jackson would not risk losing votes in Pennsylvania and other commercial states by vetoing it. Jackson reacted by saying, “The Bank is trying to kill me, Sir, but I shall kill it!”

Jackson’s opposition to the Bank became almost an obsession. Accompanied by strong attacks against the Bank in the press, Jackson vetoed the Bank Recharter Bill. Jackson also ordered the federal government’s deposits removed from the Bank of the United States and placed in smaller banks owned by his supporters. These pet banks, as Jackson’s critics called them, benefited from the sudden influx of deposits. Business interests hated Jackson for destroying the bank, but the people were with him, and he was overwhelmingly elected to a second term. Biddle retaliated by making it more difficult for businesses and others to get the money they needed, but he had already lost the political fight and the bank charter expired in 1836.

The Bank War gave Jackson a chance to display one of his most memorable qualities: he was not afraid to use the power the Constitution granted him to lead the nation from the White House. He did not see himself and Congress as co-equal branches of government. Although he understood that the Constitution limited his power, he did not defer to Congress as other presidents had. When they passed legislation he did not like, he would not hesitate to veto it. The Constitution clearly grants this power to presidents, but Jackson used the veto power, or the threat of his veto, to coerce Congress. His critics derided him as “King Andrew the First,” which was a fitting title in some cases, but not in his use of his veto power. Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

This cartoon was created by Jackson’s critics deriding his use of the veto.

JACKSON , CLAY AND CALHOUN

Henry Clay was viewed by Jackson as politically untrustworthy, an opportunistic, ambitious and self-aggrandizing man. He believed that Clay would compromise the essentials of American republican democracy to advance his own self-serving objectives. Jackson also developed a political rivalry with his Vice-President, John C. Calhoun. Throughout his term, Jackson waged political and personal war with these men, defeating Clay in the Presidential election of 1832 and leading Calhoun to resign as Vice-President.

Jackson’s personal animosity towards Clay seems to have originated in 1819, when Clay denounced Jackson for his unauthorized invasion of Spanish West Florida in the previous year. Clay was also instrumental in John Quincy Adams’s winning the Presidency from Jackson in 1824, when neither man had a majority and the election was thrown into the House of Representatives. Adams’ appointment of Clay as Secretary of State confirmed Jackson’s opinion that the Presidential election had been thrown to Adams as part of a corrupt and unprincipled bargain.

Clay was called The Great Compromiser, and served in the Congress starting in 1806. As part of his American System, Clay was unswerving in his support for internal improvements, which primarily meant federally funded roads and canals. Jackson believed the American System to be unconstitutional. Nowhere in the Constitution did it say that federal funds be used to build roads. He vetoed the Maysville Road Bill, Clay’s attempt to fund internal improvements. His veto of the Bank Recharter Bill drove the two further apart.

Jackson’s personal animosity for Calhoun seems to have had its origin in the Washington social scene of the time. Jackson’s feelings were inflamed by Mrs. Calhoun’s treatment of Peggy, wife of Jackson’s Secretary of War, John Eaton. Mrs. Calhoun and other wives and daughters of several cabinet officers refused to attend social gatherings and state dinners to which Mrs. Eaton had been invited because they considered her of a lower social station and gossiped about her private life. Jackson, reminded of how rudely his own wife Rachel was treated, defended Mrs. Eaton.

Perhaps no political issue separated Jackson from Calhoun more than states rights. Hoping for sympathy from President Jackson, Calhoun and the other states-rights party members sought to trap Jackson into a pro-states-rights public pronouncement at a Jefferson birthday celebration in April 1832. Some of the guests gave toasts that sought to establish a connection between a states-rights view of government and nullification. Finally, Jackson’s turn to give a toast came, and he rose and challenged those present, “our federal union — it must be preserved.” Calhoun then rose and stated, “The Union — next to our liberty, the most dear!” Jackson had humiliated Calhoun in public. The nullification crisis that would follow served as the last straw. Jackson proved that he was unafraid to stare down his enemies, no matter what position they might hold. Primary Source: Painting

Primary Source: Painting

Tuko-See-Mathla, one of the leaders of the Seminole Nation in Florida who, like the Cherokee, Creeks, Choctaw and other Southeastern tribes resisted and were eventually defeated by Jackson on both the battlefield and the political arena.

THE TRAIL OF TEARS

Not everyone was included in the new Jacksonian Democracy. There was no initiative from Jacksonian Democrats to include women in political life or to combat slavery. However, it was Native Americans who suffered most from Andrew Jackson’s vision of America. Jackson, both as a military leader and as President, pursued a policy of removing Native American tribes from their ancestral lands. This relocation would make room for Whites and often for speculators who made large profits from purchasing tracts of unsettled land and then reselling them in portions to individual settlers moving west.

His policy toward Native Americans caused Jackson little political trouble because his primary supporters were from the South and West where Whites generally favored a plan to remove all the tribes to lands west of the Mississippi River. While Jackson and other politicians put a positive and favorable spin on Indian removal in their speeches, the removals were in fact often brutal. There was little the Indians could do to defend themselves. In 1832, a group of about a thousand Sac and Fox led by Chief Black Hawk returned to Illinois, but militia members drove them back across the Mississippi. The Seminole resistance in Florida was more formidable, resulting in a war that began under Chief Osceola that lasted into the 1840s. Secondary Source: Map

Secondary Source: Map

A map of the route of the Cherokee Trail of Tears as well as the removal routes of other Southeastern Tribes. Their destination was “Indian Territory,” which later became the state of Oklahoma.

The Cherokee of Georgia, on the other hand, used legal action to resist. The Cherokee people were by no means frontier savages. By the 1830s, Sequoia, one of their own had developed a written version of their language. They printed newspapers and elected leaders to representative government. When the government of Georgia refused to recognize their autonomy and threatened to seize their lands, the Cherokee took their case to the Supreme Court and won a favorable decision. John Marshall’s opinion for the Court majority in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia was essentially that Georgia had no jurisdiction over the Cherokees and no claim to their lands. Georgia officials simply ignored the decision, and President Jackson refused to enforce it. Jackson was furious and personally affronted by the Marshall ruling, stating, “Mr. Marshall has made his decision. Now let him enforce it!”

Finally, federal troops came to Georgia to remove the tribes forcibly. As early as 1831, the army began to push the Choctaws off their lands to march to Oklahoma. In 1835, some Cherokee leaders agreed to accept western land and payment in exchange for relocation. With this agreement, the Treaty of New Echota, Jackson had the green light to order Cherokee removal. Other Cherokees, under the leadership of Chief John Ross, resisted until the bitter end. About 20,000 Cherokees were marched westward at gunpoint on the infamous Trail of Tears. Nearly a quarter perished on the way, with the remainder left to seek survival in a completely foreign land. The tribe became hopelessly divided as the followers of Ross murdered those who had signed the Treaty of New Echota.

Unlike the Bank War or his use of veto power, Indian Removal was not particularly controversial among Whites in his own time, but from our perspective, nearly 200 years later, Jackson’s disregard for a decision of the Supreme Court is appalling.

CONCLUSION

Andrew Jackson is an easy target for 21st Century students. He disregarded the Supreme Court and initiated the abominable Trail of Tears. He shamelessly favored his friends, even at the cost of producing an economic downturn. He was arrogant and hard to work with.

However, we must consider the times in which the people of the past lived. We hardly stop to condemn Washington or Jefferson for owning slaves. We understand that they were men of wealth in Virginia and applaud them for their enlightened thinking, even if that enlightenment did not extend as far as freeing any of their slaves during their own lifetime.

Why is it then that we are so hesitant to pardon Jackson for offenses that were popular in his own time? When the Cherokee were banished from their homeland, White America supported Jackson, not the John Marshall’s Court. If we recoil whenever we have to pay with a $20 bill because of the man honored there, why don’t we have the same reaction to the dollar? Shouldn’t we give Jackson credit for his successes? Shouldn’t we honor him for all he did for his supporters and recognize his political prowess and skill?

Or, is our money an expression of modern ideas, and not a place to be mindful of historical norms and values? What do you think? Does Jackson belong on the $20 bill?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: Andrew Jackson was a major force in American politics. As a champion of the common man, he established the spoils system, used his veto power to end the National Bank and ignored the Supreme Court when he ordered the removal of Native Americans.

Andrew Jackson changed the presidency in many ways. First, he rewarded his political supporters by giving them jobs in the government, thus creating the spoils system we are accustomed to today. He was hated by the Washington social class. They saw him as crude, and he hated them back. He believed his wife had died of shame because of their personal attacks.

Jackson reaffirmed the power of the federal government over the states. During his time in office, Senator Calhoun of South Carolina tried to promote the idea that states could nullify laws passed by Congress. In this case, they wanted to nullify the tariff they hated. Jackson won the political argument and Calhoun backed down.

Jackson hated the Bank of the United States, which he viewed as a tool of the elites to control the masses. He used his veto power to destroy the bank, depositing federal funds in banks run by his friends. As critics had warned, Jackson’s action caused a severe recession in the economy, but by then he was out of office and it was Martin Van Buren, Jackson’s protégé who suffered the political fallout.

Sometimes called King Andrew by his critics, Jackson found both legal and illegal ways to get what he wanted. He used his constitutional veto power, such as in the case of the Bank, but also simply ignored the other branches of government when it suited him.

The most egregious case was when he disregarded a Supreme Court decision that had granted the Cherokee Tribe the right to keep its land and sent the army to move them to Oklahoma. The resulting Trail of Tears is rightly remembered as both a human tragedy and a gross violation of presidential power.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Kitchen Cabinet: Nickname for the unofficial group of advisors Andrew Jackson consulted during his presidency.

John C. Calhoun: South Carolina Senator and champion of states’ rights, nullification, and the concerns of slave owners in the early 1800s.

Nicholas Biddle: President of the Second Bank of the United States who lost the political battle known as the Bank War to Andrew Jackson.

King Andrew the First: Nickname given to Andrew Jackson by his opponents deriding him for his use of veto power.

The Great Compromiser: Nickname for Henry Clay, due to his ability to craft agreements between competing sides, especially related to slavery in the decades before the Civil War.

Black Hawk: Leader of the Sac and Fox Native American tribes in the early 1800s who attempted to resettle his people in Illinois but was defeated by local militia.

Chief Osceola: Leader of the Seminole tribe in Florida who fought against removal in the early 1800s.

Cherokee: Major Native American nation in Georgia that adopted many European practices in an attempt to perpetuate their land claims but were eventually sent to Oklahoma on the Trail of Tears by Andrew Jackson.

Sequoia: Cherokee intellectual who created a written alphabet for his people.

John Ross: Leader of the Cherokee who rejected the Treaty of New Echota and fought to stay on traditional lands in Georgia.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Spoils System: System in which an incoming president appoints supports to top government posts. It was established by Andrew Jackson.

Nullification: The idea that states can ignore federal laws. This was promoted first by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in their Kentucky and Virginia Resolves and was later used by the South when they seceded at the start of the Civil War.

![]()

BANKS

Second Bank of the United States: Bank chartered in 1816 that was the subject of the Bank War and was killed off by Andrew Jackson.

Pet Banks: Regional banks owned by supporters of Andrew Jackson that received deposits of federal funds after Jackson vetoed that Second Bank of the United States.

![]()

COURT CASES

Cherokee Nation v. Georgia: 1831 Supreme court Case in which the Marshall Court decided that the government had to honor treaties made with Native Americans. Andrew Jackson ignored the Court and forced the Cherokee along the Trail of Tears.

![]()

EVENTS

Petticoat Affair: Political scandal during the Andrew Jackson Administration involving Margaret O’Neil. It resulted in a clash between Jackson and the DC social elites and highlights Jackson’s contempt for the upper classes.

Trail of Tears: Tragic forced removal of the Cherokee Nation from Georgia to Oklahoma in 1838.

![]()

LAWS & TREATIES

South Carolina Ordinance of Nullification: Law passed by South Carolina in 1832 in which the state refused to recognize the federal government’s tariff law. President Jackson forced South Carolina to follow federal law. The episode had come to be known as the nullification crisis.

Treaty of New Echota: Treaty signed by some Cherokee leaders in 1835 in which they agreed to relocate to the West in exchange for land. John Ross and other rejected the treaty.

Did John Ross recruit more people to help lead the Cherokees?

It seems to be a constant pattern in U.S. history where Native Americans are constantly being not only mistreated but attacked, was there any person that would have been able to defend/help Native American tribes that were constantly being targeted?

Given that Jackson was one of the only presidents to disobey the order of the court, how did the government change so that in the future presidents wouldn’t be able to ‘abuse’ the veto system and would be forced to listen to the decision of the court?

What happened to Chief John Ross after he resisted from the Treaty of Enchota?

Though the Petticoat Affair did mention Jackson defending “Peggy”, how did it affect Jackson’s image then and now?

At first, I thought that Peggy was in the wrong for allegedly cheating on her husband but after I saw her beauty being exploited I couldn’t even care if she cheated or not. You have your girlboss moment Peggy 030.

Did Jackson remarry after the death of his wife, Rachel Donelson?

If the Trail of Tears never happened, do you think Jackson’s reputation would be much better?

I feel there are some similarities between Alexander Hamilton and Andrew Jackson, although not as powerful as the founding father, he was able to make the economy sustainable and build systems that would support either the government or the economy. I believe their decisions play a big role in how America runs today.

What if Jackson didn’t tear down the Second Bank of the United States?

This is a link to more information about Harriet Tubman on the $20 bill: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/harriet-tubman-20-bill/2021/06/03/62443b5c-bcd1-11eb-9c90-731aff7d9a0d_story.html. I personally support this change and hope to see it happen one day.

What happened to the Cherokees after the Trail of Tears?

What about the Petticoat Affair did it show about Andrew Jackson?

When Jackson decided to veto the renewal of the Bank, did he keep in mind what the long-term effects might have been? Or was he just focused on the fact that it was a symbol of the elite having too much control over people?

If the constitution provides what they believed in, then why did they make banks even if it was said to believe that it’ll give too much federal power and why did they still own slaves?

When Jackson ignored the other branches does that show that the government is still unbalanced? Is it still unbalanced? Should more things put the president in check?

What other tribes were forced to move out?

Where did the Cherokee and other Native Tribes go after the Trail of Tears? Did they thrive there?

Did President Jackson lose a considerable amount of supporters and followers after he along with Georgia officials, blatantly ignored the rulings made from John Marshall and the Supreme Court? Did they receive any consequences after disobeying such major decisions?

I think it was quite ironic how Jackson opposed the bank and paper money and yet he is on the $20 bill.

Did Jackson’s opponents take actions to stop the spoils system? The reading says that the replacement of appointed federal officials is common today. Why is it common despite the fact that it can lead to corruption?

Despite Andrew Jackson being the “Champion of the Common Man,” why didn’t that include the Native Americans? Do you think President Jackson refusing to enforce the Supreme Court’s decision was morally right?

Why did Andrew Jackson have more popular support than Adams?

I think that Jackson had more popular support because he was known as “The Champion of the Common Man” and many of his supporters were “common men” and they supported what he believed in.

Although President Jackson was involved in some of America’s most infamous events such as the trail of tears, why is that most of people are hesistant to forgive him for siding with majority of his time? Also, why is that we learn about events such as the Trail of Tears but we do not learn the people behind this historical event and we only focus on the hardships of the thoes involved.

I wonder the same thing (in reference to your first question); some motives should be questioned but at the same time, it was a popular way of thinking at that time and many people think the opposite now days. There will always be stances/ actions taken even these days that are popular now but may be very disliked in the future.

The idea of “morally correct” seems to have changed drastically over time. Doesn’t this mean it will likely be different in 200 years so how do we determine if our judgement is “correct” when it is historically inconsistent. How do we define morality? And who should define it?

I believe we should accept the fact that nothing can stand the test of time. We can’t possibly know if our judgement will be correct in the future, but we can try our best to justify our judgement to the time we are living in. I think we define morality based on our own beliefs, and therefore the public should define morality because the public’s definition of morality will be the sum of everyone’s definition.

Did Andrew Jackson who grew up with struggles caused and helped him create a more of a democratic Nation?

Why did states back then always resisted or enacted some kind of nullification on federal laws, when they knew that the Federal Government could send federal troops to assert their power?