TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

What did it mean to think like an American? Once the colonists had thrown off the burdens and controls of England, the possibilities for political, social and artistic creativity and experimentation seemed limitless. People felt optimistic and determined that a new order would be brought to bear, not just on government but on all institutions of social interaction. Opportunity, heightened by political freedom and a surge of nationalism, caused most citizens to believe that the experiment might actually work.

Women began to explore the possibility of individual rights and equality with men. Their agenda was quite vast and included not only the right to vote but also such diverse problems as prohibition and world peace. Reformers, sure that the dire human conditions in prisons, workhouses and asylums were the result of bad institutions and not bad people, made gallant efforts to alleviate pain and suffering. Hopes were high that cures for social disorders in America caused by rapid expansion, population growth, and industrialization could work.

The nation was at peace. The Second Great Awakening’s emphasis on postmillennialism had provided a tremendous motivator for reformers and enthusiasm for change pulsated through America. If ever there was a time to make right the wrongs of the world, it was the early 1800s.

Obviously, we live in a world with a multitude of problems, so we know that our forbearers did not achieve all their goals, but that was not for lack of trying.

What do you think? Is it possible to purify society?

THE WOMEN’S SPHERE

Chaos seemed to reign in the early 1800s. Cities swelled with immigrants and farmers’ sons and daughters seeking their fortunes. Disease, poverty, and crime were rampant. Factory cities were being built almost overnight and the frontier was reaching to the Pacific Coast. The public institutions — schools, hospitals, orphanages, almshouses, and prisons — were expected to handle these problems, but were overwhelmed. Somewhere there must be safe haven from the hubbub and confusion of business and industry, a private refuge. That place was the home.

Together, a successful husband and wife created a picture of perfect harmony. As he developed skills for business, she cultivated a complementary role. This recipe for success was so popular that all who could adopted it. In short order, the newly created roles for men and women were thought to reflect their true nature. A true man was concerned about success and moving up the social ladder. He was aggressive, competitive, rational, and channeled all of his time and energy into his work. A true woman, on the other hand, was virtuous. Her four chief characteristics were piety, purity, submissiveness and domesticity. She was the great civilizer who created order in the home in return for her husband’s protection, financial security and social status.

Money equaled status, and increased status opened more doors of opportunity for the upwardly mobile. The husband had to be out in the public sphere creating the wealth, but his wife was free to manage the private sphere, the Women’s Sphere. This idea would later be dubbed by historians the Cult of Domesticity.

Women’s virtue was as much a hallmark of Victorian society as materialism. As long as women functioned flawlessly within the domestic sphere and never ventured from it, women were held in reverence by their husbands and general society. However, this was carried to ridiculous extremes. To protect women’s purity, certain words could not be spoken in their presence. Undergarments were “unmentionables.” A leg or an arm was called a “limb.” Even tables had limbs, and in one especially delicate household, the “limbs” of a piano were covered in little trousers!

The cult of true womanhood was not simply fostered by men. In fact, the promotion of women’s sphere was a female obsession as well. Writers like Sarah Hale published magazines that detailed the behaviors of a proper lady. Godey’s Lady’s Book sold 150,000 copies annually. Catherine Beecher advocated taking women’s sphere to the classroom. Women as teachers, she said, could instill the proper moral code into future generations.

It was a fragile existence for a woman. One indiscretion, trivial by today’s standards, would be her downfall, and there was no place in polite society for a fallen woman. But a fallen woman was not alone. The great majority of women never met the rigorous standard of true womanhood set by the Victorian middle class, nor could they ever hope to. Sojourner Truth drove that point home in 1851. “That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman?” Only white women of European descent, and very few of them, could be true women. For immigrant women, the wives and daughters of farmers, and the women who followed their husbands to the frontier, the necessities of daily life overshadowed the niceties. Nevertheless, the ideal of true womanhood affected every facet of American culture in the 19th century. Primary Source: Book Cover

Primary Source: Book Cover

A copy of the Godey’s Lady’s Book from 1867. This and other books gave advice to middle and upper class women. They serve as a definition of social expectations for women and help historians define the Women’s Sphere.

WOMEN’S RIGHTS

Although women had many moral obligations and duties in the home, church and community, they had few political and legal rights in the new republic. When Abigail Adams reminded her husband John during the Continental Congress to “remember the ladies!” her warning went unheeded. Women were pushed to the sidelines as dependents of men, without the power to bring suit, make contracts, own property, or vote. During the era of the Cult of Domesticity, a woman was seen merely as a way of enhancing the social status of her husband. By the 1830s and 1840s, however, the climate began to change when a number of bold, outspoken women championed reforms to address such social ills as prostitution, capital punishment, overcrowded prisons, war, alcoholism, and, most significantly, slavery.

Activists began to question women’s subservience to men and called for rallying around the abolitionist movement as a way of calling attention to all human rights. Two influential Southern sisters, Angelina and Sarah Grimke, called for women to “participate in the freeing and educating of slaves.”

Harriet Wilson became the first African-American to publish a novel sounding the theme of racism. The heart and voice of the movement, nevertheless, was in New England. Lucretia Mott, an educated Bostonian, was one of the most powerful advocates of reform, who acted as a bridge between the feminist and the abolitionist movement and endured fierce criticism wherever she spoke. Margaret Fuller wrote Women in the Nineteenth Century, the first mature consideration of feminism and edited The Dial for the Transcendental Club.

Around 1840, the abolitionist movement was split over the acceptance of female speakers and officers. Ultimately snubbed as a delegate to a World Anti-Slavery Convention in London, Elizabeth Cady Stanton returned to America in 1848 and organized the first convention for women’s rights in America, the Seneca Falls Convention, in New York. Under the leadership of Stanton, Mott, and Susan B. Anthony, the convention demanded improved laws regarding child custody, divorce, and property rights. They argued that women deserved equal wages and career opportunities in law, medicine, education and the ministry. First and foremost among their demands was suffrage, the right to vote.

The women’s rights movement in America had begun in earnest. Amelia Bloomer began publishing The Lily, which also advocated for “the emancipation of women from temperance, intemperance, injustice, prejudice, and bigotry.” She also advocated the wearing of wide pants for women that would allow for greater mobility than the expected Victorian dresses. These garments were given her name, and were known as bloomers.

The seeds of the quest for women’s rights were sown in the Declaration of Independence, claiming that “all men are created equal.” That language was mirrored in the Declaration of Sentiments created at the Seneca Falls Convention. It opens, “When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man to assume among the people of the earth a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied… We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal…”

Thus, in this era of reform and renewal women realized that if they were going to push for equality, they needed to ignore criticism and what was then considered acceptable social behavior. The new republic’s experiment in government needed all its citizens to have “every path laid open” to them. Secondary Source: Engraving

Secondary Source: Engraving

Susan B. Anthony was one of the leaders of the feminist movement of the 1800s. Her work was memorialized on a $1 coin which was minted in the 1970s.

PRISON AND ASYLUM REFORM

The pretty woman who stood before the all-male audience seemed unlikely to provoke controversy. Tiny and timid, she rose to the platform of the Massachusetts Legislature to speak. Those who had underestimated the determination and dedication of Dorothea Dix, however, were brought to attention when they heard her say that the sick and insane were “confined in this Commonwealth in cages, closets, cellars, stalls, pens! Chained, beaten with rods, lashed into obedience.” Thus, her crusade for humane hospitals for the insane, which she began in 1841, was reaching a climax.

After touring prisons, workhouses, almshouses, and private homes to gather evidence of appalling abuses, she made her case for state-supported care. Ultimately, she not only helped establish five hospitals in America, but also went to Europe where she successfully pleaded for human rights to Queen Victoria and the Pope.

In addition to the problems in asylums, prisons were filled to overflowing with everyone who gave offense to society from committing murder to spitting on the street. Men, women, children were thrown together in the most atrocious conditions. Something needed to be done.

After the War of 1812, reformers from Boston and New York began a crusade to remove children from jails into juvenile detention centers. But the larger controversy continued over the purpose of prison. Was it for punishment or penitence? In 1821, a disaster occurred in Auburn Prison that shocked even the governor into pardoning hardened criminals. After being locked down in solitary, many of the 80 men committed suicide or had mental breakdowns. Auburn reverted to a strict disciplinary approach. The champion of discipline and first national figure in prison reform was Louis Dwight. Founder of the Boston Prison Discipline Society, he spread the reformed Auburn system throughout America’s jails and added Salvation and Sabbath School to further penitence.

America enjoyed a brief period of real reform. Idealism, plus hope in the perfectibility of institutions, spurred a new generation of leaders led by the peerless Dorothea Dix. Their goals were prison libraries, basic literacy (for Bible reading), reduction of whipping and beating, commutation of sentences, and separation of women, children and the sick. By 1835, America was considered to have two of the best prisons in the world in Pennsylvania. In an unusual turn of events, reformers from Europe looked to America as a model for building, utilizing and improving their own systems. Advocates for prisoners believed that deviants could change and that a prison stay could have a positive effect. It was a revolutionary idea in the beginning of the 19th Century that society rather than individuals had the responsibility for criminal activity and had the duty to treat neglected children and rehabilitate alcoholics.

In reality it became clear that, despite intervention by outsiders, prisoners were often no better off, and often worse off, after their incarceration. Yet, in keeping with the optimistic spirit of the era, these early reformers had only begun a crusade to alleviate human suffering that continues today.

TEMPERANCE

In the late 1700s, the early temperance movement sparked to life with Benjamin Rush’s 1784 tract, An Inquiry Into the Effects of Ardent Spirits Upon the Human Body and Mind, which judged the excessive use of alcohol as injurious to physical and psychological health. Influenced by this inquiry, about 200 farmers in a Connecticut community formed a temperance association in 1789 to ban the making of whiskey. Similar associations formed in Virginia in 1800 and New York in 1808.

Over the next decade, other temperance organizations formed in eight states. Economic change and urbanization in the early 1800s was accompanied by increasing poverty that, along with various other factors, contributed to a widespread increase in alcohol use. Advocates for temperance argued that such alcohol use went hand in hand with spousal abuse, family neglect, and chronic unemployment. Americans were increasingly drinking more strong, cheap alcoholic beverages such as rum and whiskey, and pressure for inexpensive and plentiful alcohol led to relaxed ordinances on alcohol sales, which temperance advocates sought to reverse.

The movement advocated temperance, or levelness, rather than abstinence. Many leaders of the movement expanded their activities and took positions on observance of the Sabbath and other moral issues. The reform movements met with resistance from brewers and distillers. These same business owners also opposed efforts to grant women suffrage, as they feared that women would vote for temperance.

Some leaders persevered in pressing their cause forward. Americans such as Lyman Beecher, a Connecticut minister, had started to lecture fellow citizens against all use of liquor in 1825. The American Temperance Society was formed in 1826 and benefited from a renewed interest in religion and morality. Within 12 years, it claimed more than 8,000 local groups and more than 1,500,000 members. By 1839, 18 temperance journals were being published. Simultaneously, some Protestant and Catholic Church leaders were beginning to promote temperance.

The movement split along two lines in the late 1830s between moderates, who allowed some drinking, and radicals, who demanded total abstinence. A split also formed between voluntarists, who relied on moral persuasion alone, and prohibitionists, who promoted laws to restrict or ban alcohol. Radicals and prohibitionists dominated many of the largest temperance organizations after the 1830s, and temperance eventually became synonymous with prohibition.

One of the most colorful reformers of the temperance movement was Carrie Nation. She described herself as “a bulldog running along at the feet of Jesus, barking at what He doesn’t like,” and claimed a divine ordination to promote temperance by destroying bars. Sometimes accompanied by hymn-singing women, but most often alone, she would march into a bar and sing and pray while smashing bar fixtures and stock with a hatchet. Between 1900 and 1910, she was arrested some 30 times for “hatchetations,” as she came to call them. Nation paid her jail fines from lecture-tour fees and sales of souvenir hatchets.

While successful in tapping into a growing enthusiasm for social reform, the American Temperance Society failed to achieve legislative success until well into the next century when alcohol was prohibited with the ratification of the 18th Amendment. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Bible in one hand and hatchet in the other, Carrie Nation was a striking, if controversial, figure of the temperance movement.

EDUCATION REFORM

Education opportunities in the 13 colonies during the 1600s and 1700s varied considerably depending on one’s location, race, gender, and social class. Basic education in literacy and arithmetic was widely available, especially to white males residing in the Northern and Middle Colonies, and the literacy rate was relatively high among these people. Educational opportunities were much sparser for women, minorities, and poor Whites in the rural South.

Education in the United States had long been a local affair, with schools governed by locally elected school boards. Public education was common in New England where literacy had been prized since the first arrival of the Puritans, although it was often class-based with the working class receiving few benefits. Instruction and curriculum were all locally determined, and teachers were expected to meet rigorous demands of strict moral behavior. Schools taught religious values and applied Calvinist philosophies of discipline, which included corporal punishment and public humiliation for students found to be lacking.

The public education system was less organized in the South. Public schools were rare, and most education took place in the home with the family acting as instructors. The wealthier planter families were able to bring in tutors for instruction in the classics, but many yeoman farming families had little access to education.

The education reform movement began in Massachusetts when Horace Mann started the common school movement. He is often called “the father of American public education.” Arguing that universal public education was the best way to turn the nation’s unruly children into disciplined, judicious republican citizens, Mann won widespread approval from modernizers, especially in his Whig Party, for building public schools. Most states adopted one version or another of the system he established in Massachusetts, especially the program for normal schools to train professional teachers.

A common school was a public, often one-roomed school in the United States or Canada in the 1800s. Students often went to the common school from ages six to fourteen, or roughly until what we would call eighth grade. The duration of the school year was often dictated by the agricultural needs of the community, with children on vacation from school when they needed to work on the family farm. Common schools were funded by local taxes, did not charge tuition, and were open to all White children.

Mann advocated a statewide curriculum and instituted school financing through local property taxes. Mann also fought protracted battles against the Calvinist influence on discipline, preferring positive reinforcement to physical punishment.

Private academies that served students after eighth grade flourished in towns across the country. Change was slow, but by the close of the 1800s, public high schools began to outnumber private ones. However, in rural areas where most people lived, there were few secondary schools before the 1900s.

Other reforms included kindergartens introduced by German immigrants, while New England orators sponsored the lyceum movement that provided open lectures for hundreds of towns and small cities. Mann advocated the Prussian model of schooling, which included the technique separating the school into levels by age. Students were assigned by age to different grades and progressed through them. Some students progressed with their grade and completed all courses the secondary school had to offer. These students were graduated, and awarded a certificate of completion.

Colleges also began to change in the mid-1800s. At the onset of the Industrial Revolution, the nation’s many small colleges helped young men make the transition from rural farms to complex urban occupations. These colleges prepared ministers and provided towns across the country with a core of community leaders. The more elite colleges became increasingly exclusive and contributed relatively little toward upward social mobility. By concentrating on the offspring of wealthy families, ministers, and a few others, prestigious eastern colleges, especially Harvard, played an important role in the formation of a northeastern elite with great power. Secondary Source: Map

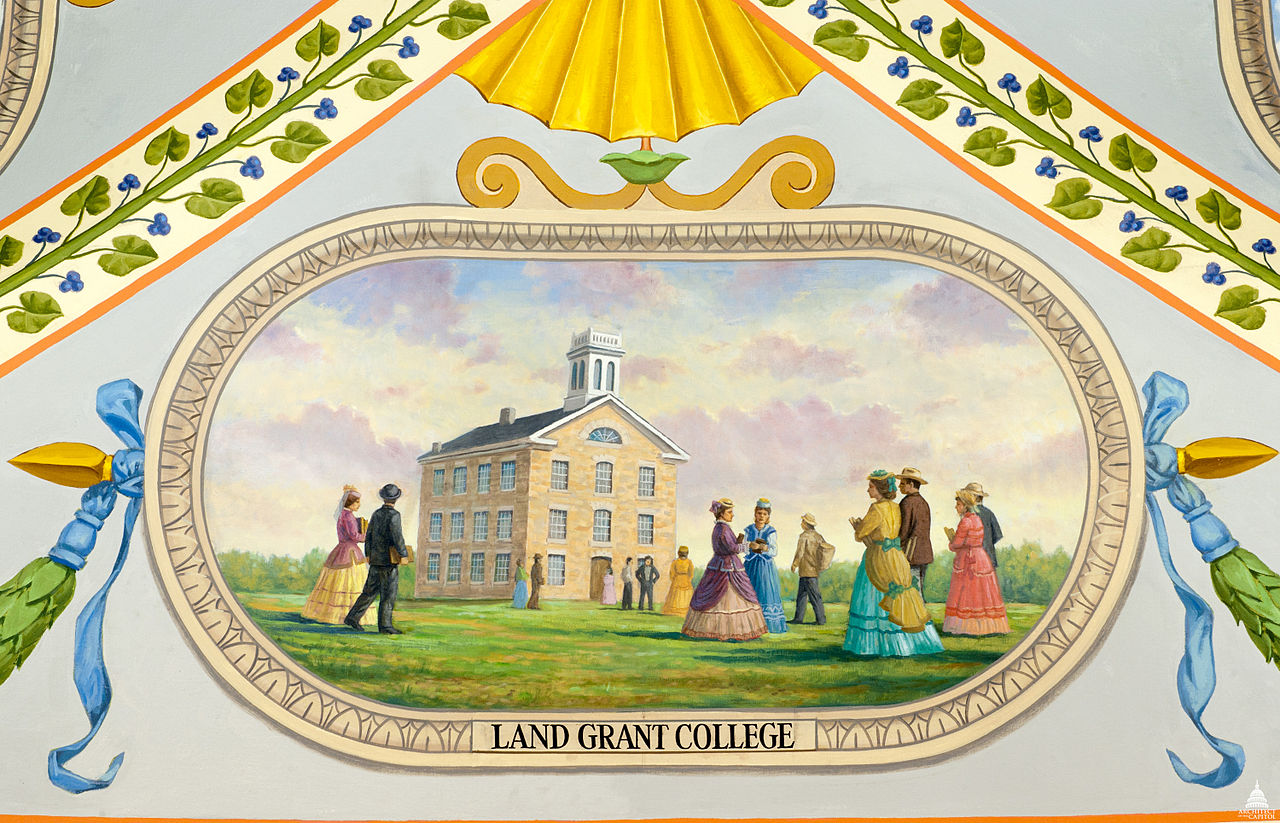

Secondary Source: Map

A map showing all of the land grant colleges and universities in the United States. Clearly the Morrill Acts were an enormous boost for the availability of American postsecondary education.

This began to change with the passage of the Morrill Land-Grant Acts, a set of laws signed by President Abraham Lincoln that allowed for the creation of land-grant colleges. Under the act, each eligible state received a total of 30,000 acres of federal land for each member of Congress held by the state. This land, or the proceeds from its sale, was to be used for establishing and funding educational institutions. The land-grant college system produced the system of public state universities ubiquitous in America today and helped make the United States a world leader in post-secondary education.

CONCLUSION

Reformers in the early 1800s took up the causes of education, women’s rights, prison reform, mental healthcare, and temperance. They sought out evil, confronted it, and tried to banish it from American life (sometimes even with hatchets).

They certainly left their mark. The millions of Americans who have degrees from state universities or all who simply attended a high school can thank the reformers of that era. We can scarcely imagine a world in which women cannot vote, students pay for school, the mentally ill and convicts alike are housed in decrepit prisons and alcoholism is commonplace rather than stigmatized.

But for all they tried, the pioneering reformers of the first half of the 19th Century were not able to purify humanity. We still have dangerous prisons, expensive colleges, high school dropouts, restrictions on voting, homeless alcoholics, and gender inequality.

Is the goal of purifying humanity possible? What do you think?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The spirit of reform brought about by the Second Great Awakening led to movements to improve many areas of life including temperance, education, women’s rights, mental health, and abolition.

Some serious social reform movements developed in the early 1800s. Women began organizing and advocating for equal rights. This was in part due to the rise of the idea that the Woman’s Sphere was in the home. An outgrowth of the industrial revolution, this idea is still prevalent in American society. The suffrage movement began when reformers met at Seneca Falls, New York to organize. Their Declaration of Sentiments marks an important beginning for the effort by women to win the right to vote.

Dorothea Dix and Louis Dwight worked to improve conditions in mental asylums and jails.

A temperance movement developed to work toward a ban on alcohol consumption. Most members of the movement were practical, but Carrie Nation made headlines by attacking bars with her hatchet and Bible.

Horace Mann worked to reform schools. In the North, common schools were built to use taxpayer dollars to provide basic education for all children through eighth grade. Mann build normal schools to train teachers. Congress allocated funding for land to build universities in each state, the beginning of the public university system.

Much of the spirit of reform at this time was inspired by the Second Great Awakening’s teaching that a pure society full of perfected people would hasten the return of God.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Abigail Adams: Wife of the second president. She is remembered as an early champion for women’s rights.

Angelina and Sarah Grimke: Sisters from the South in the early 1800s who promoted women’s rights and the abolition of slavery.

Harriet Wilson: African-American female novelist of the early 1800s.

Lucretia Mott: Boston reformer and champion of women’s rights in the early 1800s. Along with Stanton and Anthony, she helped organize the Seneca Falls Convention.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Champion of women’s rights in the early 1800s. Along with Mott and Anthony, she helped organize the Seneca Falls Convention.

Susan B. Anthony: Champion of women’s rights in the early 1800s. Along with Mott and Stanton, she helped organize the Seneca Falls Convention.

Amelia Bloomer: Women’s rights advocate in the 1800s and publisher of The Lily. She tried to make wearing pants social acceptable for women.

Dorothea Dix: Social reformer of the 1800s who worked especially to improve the conditions of jails and mental asylums.

Louis Dwight: Founder of the Boston Prison Discipline Society. Along with Dorothea Dix, he helped reform prisons in the 1800s.

Lyman Beecher: Connecticut minister in the 1800s who co-founded the American Temperance Society.

American Temperance Society: Organization founded in 1826 to encourage limiting or banning of alcohol.

Carrie Nation: Temperance advocate of the late 1800s who famously entered bars to preach while chopping the bars to pieces with a hatchet.

Horace Mann: Champion of education reform during the 1800s. He is remembered as the founder of public education.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Women’s Sphere: Idea popularized in the early 1800s with the onset of the Industrial Revolution that certain tasks and issues were appropriate for women. These did not include work outside the home or politics. This has also been called the Cult of Domesticity.

Cult of Domesticity: Idea popularized in the early 1800s with the onset of the Industrial Revolution that certain tasks and issues were appropriate for women. These did not include work outside the home or politics. This has also been called the Women’s Sphere.

Feminism: Political movement to establish equal status for women.

Suffrage: The right to vote.

Universal Public Education: The idea that all children should have the opportunity to attend schools for free that are funded by tax dollars. It was a key idea promoted by Horace Mann in the 1800s.

![]()

DOCUMENTS

“Remember the Ladies!” Quote from one of Abigail Adams’ letters to John Adams during the debate over the Declaration of Independence in which she urged him to consider women’s rights in the establishment of the nation.

Declaration of Sentiments: Statement adopted at the Seneca Falls Convention arguing for acceptance of more rights for women, including the right to vote.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Normal Schools: Colleges designed to prepare future teachers. They were championed by Horace Mann in the 1800s.

Common Schools: Free public schools in the 1800s that taught students up to the eighth grade.

Land-Grant Colleges: State universities created under the Morrill Acts in the 1860s.

![]()

EVENTS

Seneca Falls Convention: The first major meeting of women’s rights advocates in America, which occurred in New York in 1848.

Temperance: Movement to reduce the use of alcohol, and eventually to ban alcohol entirely.

Common School Movement: Movement in the 1800s founded by Horace Mann to establish public schools.

![]()

LAWS

Morrill Land-Grant Acts: A collection of laws signed by Abraham Lincoln in the 1860s setting aside land for states to establish universities. They created the system of state universities that is familiar today.

![]()

FASHION

Bloomers: Wide pants worn by women in the 1800s.

What happened to the bars that Carrie Nation destroyed? Were they rebuilt or just damaged?

What were some of the problems Horace Mann faced building common schools?

Did anything happen Angelina and Sarah Grimke for living in the South and being abolitionists?

While women during this advocated for more rights, did they ever actually see any success at the time, or were they just badly looked down upon by the rest of society including other women?

Jobless women from that time seems no different from present day bored housewives who like to gossip.

Was the universal white manhood suffrage beneficial or detrimental to slave and women’s rights in the long run of things?

Oops wrong reading :p

During the Temperance movement, did farmers still create alcohol out of their crops for easy transportation, or did the industrial revolution make it so that they could transfer the wheat itself?

Did Harriet Wilson get any backlash from publishing his book?

I feel like we still see this issue today where women still aren’t given those equal chances, whether it be in the workforce or their rights as women and how they are able to use their body. Which I feel like those people are speaking because of how they don’t understand where a woman’s body has gone through and what sort of pain they may have endured.

Were there any women back then who refused to wear bloomers or despised the idea of wearing them?

What would happen to the women who didn’t meet their social standards? Would they end up not being married?

With the education reform, how much does it differ from the current education system?

I wonder why there was not as much influence for these reforms before this time period. Did people not think that the problems were bad or did they know of them and just did not want to help make that change?

Who came up with the idea of the home where husbands would go work and women would stay at home?

I wonder why women advocated for the cult of true womanhood.

Why was the idea of being an ideal women so strict?

Why were only white women of European descent able to be true women?

I find it interesting how men did not want women to have the right to vote because they did not want their drinking rights taken away. It is just interesting.

The reformers in the early 1800s did a lot of great things. Why is college not free while schools did not charge tuition?

Despite all the hard work being done by women, why did they still have so few political rights? Elizabeth Cady Stanton had organized the first women’s Convention in America and many other things had occurred, but women still didn’t get their rights. Why was this? Did women have that little power compared to men?

Within the category of Women’s Rights, women such as Susan B. Anthony, both of the sisters Angelina and Sarah Grimke, and many more got hate along with people agreeing and moving with them at the same time. If you were them how would you react to the hate and disagreement? Would you choose to hold your head high? Or back off from the “spotlight” and go behind the scenes?

Were there women who felt satisfied with the picture of the “perfect harmony” concept? If so, why?

Did the Common School Movement or public education originally include minority groups, such as the African Americans & other immigrant children? Did they receive the same education as the Whites did?

What led to the rise of the women’s movement and what impact did it have on American society?

Women being excluded from society despite their contributions led to the rise of the Women’s movement. It made a huge impact on American society because it changed the way we see Women and the rights given to women.

Do you remember the video we watched about the impact of the Revolution on women? The move toward Republican Motherhood set off the shift in thinking that eventually laid the groundwork for the rise of the women’s rights movement.

Why is that during this period of reform that America two of the best prisons in the world in Pennsylvania, and why is that when the reformers that were being involved in starting a crusade, continue to allevate human suffering in prisons that still continue to exsist?

If women were teachers for the future generation, to raise patriotic sons and daughters, why did men and society want women to stay within their “Women Sphere”? If the Women Sphere included not working outside of home or politics, how were the women supposed to raise and teach patriotic sons and daughters for the next generation?

I think the idea of women staying inside their “sphere” involved men wanting women to stay inferior to them. By staying in their “sphere”, this allowed men to have authority over them.

Did the mass incarceration of individuals during the 1800s actually make America safer?

What was society’s reaction to women speaking up, demanding equal rights, and leading social reforms?

How did Americans originally view tattoos? Was it taboo as well? I find that tattoos are more socially accepted now but they are still considered unacceptable in certain workplaces and seen as gang related. We need to make progress despite how far we’ve come.