TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

Thomas Jefferson had dreamed of America as a land of independent, self-sufficient, noble farmers. In Jefferson’s mind, these yeomen farmers, as he called them, were the bedrock of a truly democratic society. They were connected to the land, did not rely on others, and would form the foundation of a pure, uncorrupted base of voters to wisely guide the nation. Unlike the merchants, traders, artisans and factory workers of Alexander Hamilton’s America, they could not be manipulated or coerced.

We know, of course, that Jefferson’s vision for America did not come to pass. It is a Hamiltonian world that we live in. Why is this? How did it happen that commerce, industry, banking and trade toppled noble agriculture as the preeminent pillar in American society?

Why didn’t America become a land of yeoman farmers?

THE CANAL ERA

Ever since the days of Jamestown and Plymouth, America was moving west. Trail blazers had first hewn their way on foot and by horseback. Homesteaders followed by wagon and by either keelboat or bargeboat, bringing their possessions with them. Yet, real growth in the movement of people and goods west started with the canal.

For over a hundred years, people had dreamed of building a canal across New York that would connect the Great Lakes to the Hudson River, New York City and the Atlantic Ocean. After unsuccessfully seeking federal government assistance, Dewitt Clinton successfully petitioned the New York State legislature to build the canal and bring that dream to reality. Clinton’s Ditch, his critics called it.

Construction began in 1817 and was completed in 1825. The canal spanned 350 miles between the Great Lakes and the Hudson River and was an immediate success. Between its completion and its closure in 1882, it returned over $121 million in revenues on an original cost of $7 million. Its success led to the great canal age. By bringing the Great Lakes within reach of a metropolitan market, the Erie Canal opened up the unsettled northern regions of the Old Northwest Territory: Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin and Illinois. It also fostered the development of many small industrial companies, whose products were used in the construction and operation of the canal. Primary Source: Lithograph

Primary Source: Lithograph

A depiction of the locks along the Erie Canal at Lockport, NY, where canal boats like the one on the left are raised and lowered.

New York City became the principal gateway to the West and financial center for the nation. The Erie Canal was also in part responsible for the creation of strong bonds between the new western territories and the northern states. The flat lands of the West were cleared, plowed, and turned into productive farmland. The canal enabled the farmers to send their goods to New England. With food being produced elsewhere and brought to consumers by canal, fewer subsistence farmers were needed in the North to feed the population. Many farmers left for jobs in the factories.

Pennsylvanians were shocked to find that the cheapest route to Pittsburgh was by way of New York City, up the Hudson River, across New York by the Erie Canal to the Great Lakes, with only a short overland trip from Lake Erie to Pittsburgh. When it became evident that little help for state improvements could be expected from the federal government, other states followed New York in constructing canals. Ohio built a canal in 1834 to link the Great Lakes with the Mississippi Valley. As a result of Ohio’s investment, Cleveland rose from a frontier village to a Great Lakes port by 1850. With the canal, Cincinnati could send food products down the Ohio and Mississippi by flatboat and steamboat and ship flour by canal boat to New York.

Spurred on by their neighbors, leaders in Pennsylvania put through a great portage canal system to Pittsburgh. It used a series of inclined planes and stationary steam engines to transport canal boats up and over the Allegheny Mountains on rails. At its peak, Pennsylvania had almost a thousand miles of canals in operation. By the 1830s, the country had a complete water route from New York City to New Orleans, and by 1840, over 3,000 miles of canals had been built. Yet, within 20 years a new mode of transportation, the railroad, would put most of them out of business. Secondary Source: Map

Secondary Source: Map

The many canals of the early Industrial Revolution. Before railroads, these canals spurred the development of the market revolution and waves of immigration into the Midwest.

EARLY RAILROADS

The development of railroads was one of the most important phenomena of the Industrial Revolution. With their formation, construction and operation, they brought profound social, economic and political change. Over the next 50 years, America would come to see magnificent bridges and other structures on which trains would run, awesome depots, ruthless rail magnates and the majesty of rail locomotives crossing the country.

The railroad was first developed in Great Britain. A man named George Stephenson successfully applied the steam technology of the day and created the world’s first successful locomotive. The first engines used in the United States were purchased from the Stephenson Works in England. Even rails were largely imported from England until the Civil War. Americans who had visited England to see new steam locomotives were impressed that railroads dropped the cost of shipping by carriage by 60-70%.

Baltimore, the third largest city in the nation in 1827, had not invested in a canal. Yet, Baltimore was 200 miles closer to the frontier than New York and soon recognized that the development of a railway could make the city competitive with New York and the Erie Canal in transporting people and goods to the West. The result was the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the first railroad chartered in the United States. There were great parades on the day the construction started. On July 4, 1828, the first spade full of earth was turned over by the last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence, 91-year-old Charles Carroll.

New railroads came swiftly. In 1830, the South Carolina Canal and Rail-Road Company was formed to draw trade from the interior of the state. It had a steam locomotive built at the West Point Foundry in New York City, called The Best Friend of Charleston, the first steam locomotive to be built for sale in the United States. A year later, the Mohawk & Hudson railroad reduced a 40-mile wandering canal trip that took all day to accomplish to a 17-mile trip that took less than an hour. Its first steam engine was named the DeWitt Clinton after the builder of the Erie Canal.

Although the first railroads were successful, attempts to finance new ones failed at first as opposition was mounted by turnpike operators, canal companies, stagecoach companies and wagon drivers, tavern owners and innkeepers whose businesses were threatened. Sometimes opposition turned to violence. Religious leaders decried railroads as sacrilegious. But the economic benefits of the railroad won over the skeptics.

A note on railroad names: Most railroads were named after the two places they connected, or where they generally operated. For example, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad line went between the city of Baltimore in Maryland and the state of Ohio. To simplify things, most people began calling the railroads by their initials and the companies themselves used their initials on the sides of locomotives and railroad cars. Everyone knew, for example, what the B&O was.

INVENTORS AND INVENTIONS

A nation becomes great because of great people. Often the people that make the greatest impact on progress are not national leaders, but brilliant men and women of ideas. A handful of individuals developed inventions in the first half of the 1800s that not only had a direct impact on everyone’s lives, but also affected the destiny of the American nation.

In the second decade of the nineteenth century, roads were few and poor. Getting to the frontier and instituting trade with settlers was difficult. In 1807, Robert Fulton sailed the first commercially viable steamboat, the Clermont, on the Hudson River from New York City to Albany. Steamboats could sail upstream against the current. Before Fulton’s innovation, merchants in the North built flatboats that they loaded with goods and floated with the current downstream. After unloading, they sold the boats for scrap wood and proceeded home overland since there was no way to propel a flatboat upriver. However, within four years, regular steamboat service from Pittsburgh took passengers and cargo down the Ohio River to ports along the Mississippi as far as New Orleans, and then back again. Within 20 years, over 200 steamboats were plying these routes.

While New England was moving to mechanize manufacturing, others were working to mechanize agriculture. Cyrus McCormick wanted to design equipment that would simplify farmers’ work. In 1831, he invented a horse-drawn reaper to harvest grain and started selling it to others in 1840. It allowed the farmer to do five times the amount of harvesting in a day than they could by hand using a scythe. By 1851, his company was the largest producer of farm equipment in the world. Primary Source: Design

Primary Source: Design

Cyrus McCormick’s design for a reaper in 1845. The tongue on the right would be attached to a team of horses.

In 1837, John Deere made the first commercially successful riding plow. Deere’s steel plow allowed farmers to turn heavy, gummy prairie sod easily, which stuck to the older wooden and iron plows. His inventions made farm less physically demanding. During the Civil War, 25 years later, women and young children of the South would use these devices when the men were away at war.

Another notable American inventor was Samuel Morse, who invented the telegraph and Morse Code. Morse was an artist having a great deal of difficulty making enough money to make ends meet. He started pursuing other business opportunities that would allow him to continue his work as an artist. Out of these efforts came the telegraph, a machine that sent electrical signals over wires. His code was a set up long and short pulses that represented each letter of the alphabet and the numbers 0-9. A telegraph operator at one end tapped out a message in code, and at the other end, another operator listed and decoded the message onto paper. With the completion of the first telegraph line between Baltimore and Washington in 1844, almost instant communication between distant places in the country was possible. The man who was responsible for building this first telegraph line was Ezra Cornell, later the founder of Cornell University. It was not long before there were telegraph offices in almost every town and young boys were seen riding their bikes to deliver the messages the office received. Telegraph companies eventually went into the financial business as well. People could pay the company at one office, and “wire” money to their friends, family, or business associates far way where that telegraph office would take their cash on hand and deliver it, all for a fee, of course. The most famous of these companies was the ubiquitous Western Union.

Charles Goodyear invented one of the most important chemical processes of the century. Natural rubber is brittle when cold and sticky when warm. In 1844, Goodyear received a patent for developing a method of treating rubber called vulcanization, which made it strong and supple when hot or cold. Although, the process was instrumental in the development of tires used on bicycles and automobiles, the fruit of this technology came too late for Goodyear and he died a poor man.

Perhaps no one had as great an impact on the development of the industrial North as Eli Whitney. Whitney lived in an age where an artisan would handcraft each part of every gun. No two products were quite the same. Whitney raised eyebrows when he walked into the US Patent office, took apart ten guns, and reassembled them mixing the parts of each gun. Whitney’s milling machine allowed workers to cut metal objects in an identical fashion, making interchangeable parts. It was the start of the concept of mass production. Over the course of time, the device and Whitney’s techniques were used to make many others products. Elias Howe used it to make the first workable sewing machine in 1846. Clockmakers used it to make metal gears. In making the milling machine to produce precision guns and rifles in an efficient and effective way, he set the industrial forces of the North in motion.

THE FIRST AMERICAN FACTORIES

There was more than one kind of frontier and one kind of pioneer in early America. While many people were trying to carve out a new existence in states and territories continually stretching to the West, another group pioneered new, large forms of business enterprise that involved the use of power-driven machinery to produce products and goods previously produced in the home or small shops. Part of the technology used in forming these new business enterprises came from England, however, increasingly they came from American inventors and scientists and mechanics.

The first factory in the United States was begun after George Washington became President. In 1790, Samuel Slater, a cotton spinner’s apprentice who left England the year before with the secrets of textile machinery, built a factory from memory to produce spindles of yarn.

The factory had 72 spindles, powered by nine children pushing foot treadles, soon replaced by waterpower. Three years later, John and Arthur Shofield, who also came from England, built the first factory to manufacture wool in Massachusetts.

From these humble beginnings in 1790, the Industrial Revolution spawned growth in factories and, mill towns, and eventually large cities in the North. By the time the Civil War began 70 years later, there were over two million spindles in over 1200 cotton factories and 1500 woolen factories in the United States.

From the textile industry, the factory system spread to many other areas. In Pennsylvania, large furnaces and rolling mills supplanted small local forges and blacksmiths. In Connecticut, tin ware and clocks were manufactured. Soon, factories were producing everything from reapers to sewing machines. Primary Source: Drawing

Primary Source: Drawing

The Boston Manufacturing Company sits aside on of New England’s many rivers, providing the waterpower necessary to turn the factory’s machines. Eventually, steam power made it possible to build factories anywhere.

At first, these new factories were financed by business partnerships, where several individuals invested in the factory and paid for business expenses like advertising and product distribution.

Shortly after the War of 1812, a new form of business enterprise became prominent: the corporation. Similar to the joint stock company of colonial times, in a corporation, individual investors are financially responsible for business debts only to the extent of their investment, rather than extending to their full net worth, which might include a house and other property.

First used by bankers and builders, the corporation spread to manufacturing. In 1813, Frances Cabot Lowell combined financing from both family members and other investors and formed the Boston Manufacturing Company to build America’s first integrated textile factory, which performed every operation necessary to transform cotton lint into finished cloth. Frances Cabot Lowell and his associates hoped to avoid the worst evils of British industry. They built their production facilities at Waltham, Massachusetts. To work in the textile mills, Lowell hired young, unmarried women from New England farms. The mill girls were chaperoned by matrons and were held to a strict curfew and moral code. He chartered additional companies in Massachusetts and New Hampshire that replicated their idea. Other entrepreneurs copied their corporation model and by 1840 the corporate manufacturer was commonplace.

Although the work was tedious (12 hours per day, 6 days per week), many women enjoyed a sense of independence they had not known on the farm. The wages were triple the going rate they could earn as domestic servants.

The impact of the creation of all these factories and corporations was to drive people from rural areas to the cities where factories were located. During the 1840s, the population of the country as a whole increased by 36%. The population of towns and cities of 8,000 or more increased by 90%. With a huge and growing market of customers, the corporation became the central force in America’s economic growth.

Changes brought about by improved transportation, communication, production and business organization led to a shift historians call the market revolution. Americans could now buy and sell products far from where they lived. Subsistence farming decreased. Fewer people worked for themselves. If food could be transported, cities were possible where no one was a farmer. The market revolution was by no means an overnight occurrence, but the nature of American production, consumption and commerce was radically different at the outset of the Civil War in 1860 then what it had been at the end of the War of 1812.

IRISH AND GERMAN IMMIGRATION

In the middle half of the 19th Century, more than one-half of the population of Ireland immigrated to the United States. So did an equal number of Germans. Most of them came because of civil unrest, severe unemployment or almost inconceivable hardships at home. This wave of immigration affected almost every city and almost every person in America. From 1820 to 1870, over seven and a half million immigrants came to the United States — more than the entire population of the country in 1810. Nearly all of them came from Northern and Western Europe, about a third from Ireland and almost a third from Germany. Burgeoning companies were able to absorb anyone who wanted to work. Immigrants built canals and constructed railroads. They became involved in almost every labor-intensive endeavor in the country. They built much of the country. Primary Source: Illustration

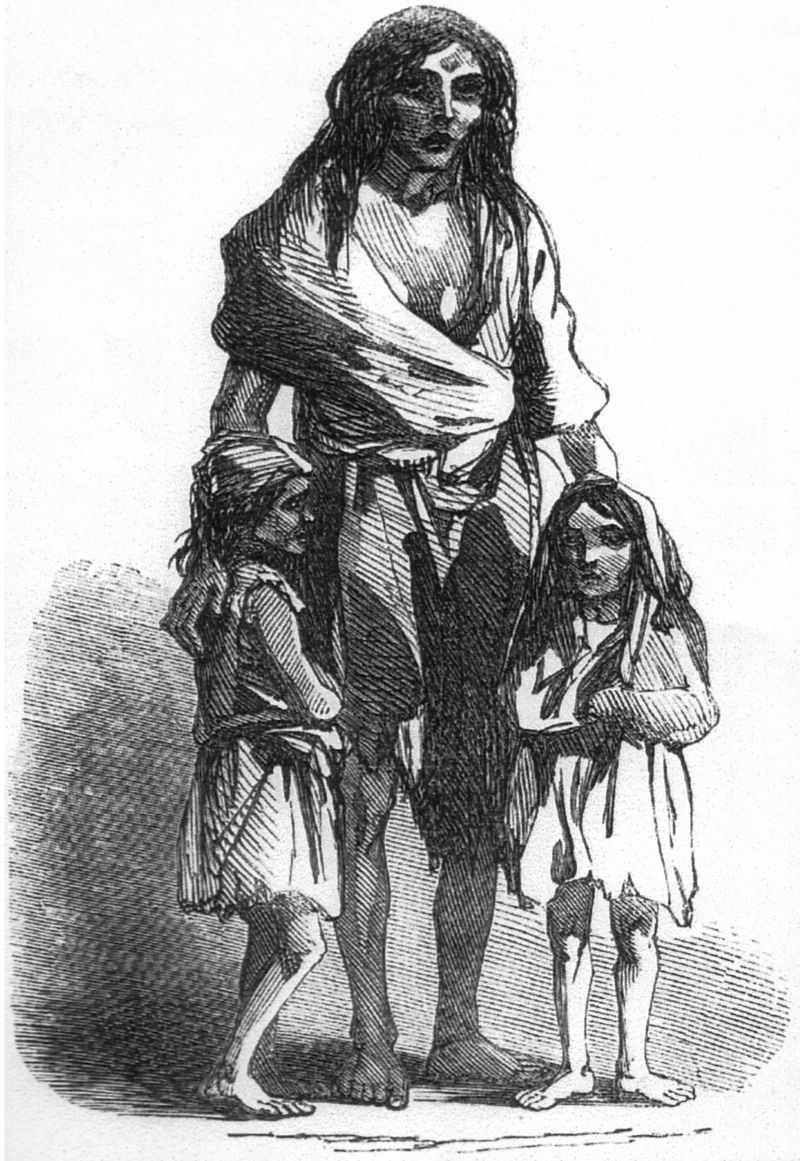

Primary Source: Illustration

A famous depiction of a mother and children escaping the Irish Potato Famine.

In Ireland almost half of the population lived on farms that produced little income. Because of their poverty, most Irish people depended on potatoes for food. When this crop failed three years in succession and when mold destroyed potatoes stored for the winters, it led to the a Great Famine with horrendous consequences. Over 750,000 people starved to death. Over two million Irish eventually moved to the United States seeking relief from their desolated country. Impoverished, the Irish could not buy property. Instead, they congregated in the cities where they landed, almost all in the northeastern United States. Today, Ireland has just half the population it did in the early 1840s and there are more Irish Americans than there are people in the whole of Ireland itself.

In the decade from 1845 to 1855, more than a million Germans fled to the United States to escape economic hardship. They also sought to escape political unrest caused by riots, rebellion and a revolution in 1848. The Germans had little choice. Few other places besides the United States allowed German immigration. Unlike the Irish, many Germans had enough money to journey to the Midwest in search of farmland and work. The largest settlements of Germans were in New York City and Baltimore in the East, Cincinnati, St. Louis and Milwaukee in the Midwest. One of the legacies of this migration are the German breweries, including Anheuser-Busch in St. Louis.

With vast numbers of German and Irish coming to America, hostility toward them erupted, in part due to religious intolerance as all of the Irish and many of the Germans were Roman Catholic. Part of the opposition was political. Most immigrants living in cities became Democrats because the party focused on the needs of commoners. Part of the opposition occurred because Americans in low-paying jobs felt threatened and feared being replaced by new arrivals willing to work for almost nothing. Signs that read NINA — “no Irish need apply” — sprang up throughout the country.

Ethnic and anti-Catholic rioting occurred in many northern cites, the largest occurring in Philadelphia in 1844 during a period of economic depression. Protestants, Catholics and local militia fought in the streets. 16 were killed, dozens were injured and over 40 buildings were demolished. Nativist political parties sprang up almost overnight. The most influential of these parties, the Know Nothing Party, was anti-Catholic and wanted to extend the amount of time it took immigrants to become citizens and voters. They also wanted to prevent foreign-born people from ever holding public office. Economic recovery after the 1844 depression reduced the number of serious confrontations for a time, as the country needed all the labor it could get and competition for jobs decreased.

But nativism returned in the 1850s with a vengeance. In the 1854 elections, nativists won control of state governments in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Hampshire and California. They won elections in Maryland and Kentucky and took 45% of the vote in five other states.

THE AMERICAN SYSTEM

From his entry into politics in the first decade of the 1800s until his death in 1852, Henry Clay was a dominating force in American politics. A champion of the interests of the West and leader of the Whig Party, Clay served as both Secretary of State and Speaker of the House of Representatives. He was involved in or responsible for many of the most important pieces of legislation during the first half of the 1800s.

During the Industrial Revolution, Clay championed what was known as the American System of high tariffs, a national bank, and federally sponsored internal improvements of canals and roads. Once in office, President John Quincy Adams embraced Clay’s American System and proposed a national university and naval academy to train future leaders of the republic. Clay envisioned a broad range of internal transportation improvements. Using the proceeds from land sales in the West, Adams endorsed the creation of roads and canals to facilitate commerce and the advance of settlement in the West. Secondary Source: Photograph

Secondary Source: Photograph

This is modern view the Petersburg Toll House on the National Road in Addison, Pennsylvania. Toll houses like these were common along the roads of the early 1800s. Travelers would stop to pay since the construction and maintenance of the roads were private ventures. Like the canals and railroads of the time, there might have been government money to initiate the project, but they were not government run services the way we think of roads and highways today.

Many in Congress vigorously opposed federal funding of internal improvements, citing among other reasons that the Constitution did not give the federal government the power to fund these projects and the president’s opponents smelled elitism in these proposals and pounced on what they viewed as the administration’s catering to a small privileged class at the expense of ordinary citizens. However, in the end, Adams succeeded in extending the Cumberland Road into Ohio. He also broke ground for the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal on July 4, 1828.

Tariffs, which both Clay and Adams promoted, were not a novel idea. Since the birth of the republic, they had been seen as a way to advance domestic manufacturing by making imports more expensive. Congress had approved a tariff in 1789, and Alexander Hamilton had proposed a protective tariff in 1790. Congress also passed tariffs in 1816 and 1824. Clay spearheaded the drive for the federal government to impose high tariffs. If imported goods were more expensive than domestic goods, then people would buy American-made goods.

President Adams wished to promote manufacturing, especially in his home region of New England. To that end, in 1828 he proposed a high tariff on imported goods, amounting to 50% of their value. The tariff raised questions about how power should be distributed, causing a fiery debate between those who supported states’ rights and those who supported the expanded power of the federal government. Those who championed states’ rights denounced the 1828 measure as the Tariff of Abominations, clear evidence that the federal government favored one region, in this case the North, over another, the South. They made their case by pointing out that the North had an expanding manufacturing base while the South did not. Therefore, the South imported far more manufactured goods than the North, causing the tariff to fall most heavily on the southern states. The enactment of the tariff led to the Nullification Crisis, one of the most severe tests of the Union before the Civil War.

CONCLUSION

Most Americans in the early 1800s were farmers. In fact, it was not until 1900 that more than half of all Americans lived in cities, but the trend was clearly established by the time the middle of the 19th Century had arrived. Hamilton’s vision for America is our world, not Jefferson’s world of yeoman farmers.

But why is this? Why is it that Jefferson’s vision, so noble and egalitarian, did not survive the test of time?

What do you think? Why isn’t America a land of yeomen farmers as Jefferson had envisioned?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The industrial revolution began in the early 1800s and led to major changes in transportation, communication, manufacturing, and the way the economy worked.

In the first half of the 1800s, the United States experienced a new sort of revolution. This change dealt with transportation, communication, and economics.

New forms of transportation made it much easier to move goods from one part of the country to another. Many canals were built, most importantly the Erie Canal. The Erie Canal opened in 1825 and connected New York City to the Great Lakes. After it opened, many people from New York and New England moved into the Midwest. The expansion of trade through New York City fostered growth and solidified it as America’s largest city and the center of the nation’s trade.

This time in history also saw the construction of the nation’s first railroads. Although they were few in number, railroads later eclipsed canals as the primary means of moving people and products.

American inventors were especially prolific in the early 1800s. The steamboat which allowed ships to move upriver, the horse-drawn reaper that allowed farmers to harvest much larger fields, the riding plow that allowed the tilling of thick prairie soil, and interchangeable parts were all developed at this time.

The first factories developed in the early 1800s. Based primarily in New England near rivers where they could draw waterpower, the early factories produced textiles and employed young women who sometimes lived in company dormitories. The Lowell Mills were the most famous example of these.

All of these changes led to the market revolution. Because transportation was improved, products could be shipped far from where they were produced. Thus, instead of growing one’s own food, or trading with neighbors, Americans could send products far away to sell, and buy things that were imported to their region.

Much of the labor in the nation’s factories and building canals and railroads was done by immigrants. In the early 1800s, many were from Germany and Ireland. The Irish came to escape the Potato Famine and faced intense anti-Catholic nativist discrimination.

It was during this time that Senator Henry Clay proposed the American System. He wanted tariffs to protect American producers, a national bank to support business, and federal funding for roads, canals and other internal improvements that could foster growth. Southerners resisted a tariff signed by John Quincy Adams since it protected Northern producers but made imports to the South more expensive.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Dewitt Clinton: Entrepreneur who built the Erie Canal.

Robert Fulton: Entrepreneur who built the first commercially successful steamboat. His ship, the Clermont, sailed between New York City and Albany along the Hudson River.

Cyrus McCormick: Inventor of a horse-drawn reaper. His company became a major producer of farm equipment.

John Deere: Inventor of a riding plow that allowed farmers to turn thick prairie soil into profitable farmland.

Samuel Morse: Inventor of the telegraph and the code that bears his name.

Charles Goodyear: Inventor of vulcanization, a chemical process that for treating rubber so that it could be used in both hot and cold conditions.

Eli Whitney: Inventor who pioneered the use of interchangeable parts and invented the cotton gin.

Elias Howe: Inventor of a sewing machine in 1846.

Samuel Slater: Entrepreneur who opened the first factory in America. He learned the textile industry in England and replicated it in the United States.

Frances Cabot Lowell: Entrepreneur of the early Industrial Revolution. He opened the Boston Manufacturing Company and integrated all steps of the textile industry.

Mill Girls: Unmarried young women who worked in the Lowell Mills in Massachusetts. They were paid well and lived in a company town, but had strict limitations on behavior.

Known Nothing Party: Political party that was active in the 1850s. They promoted nativist policies in response to increased immigration, especially by Catholic Irish and Germans. They were renamed the American Party.

Henry Clay: American statesman who served as Secretary of State and Speaker of the House of Representatives. He was the leading Whig politician of the early 1800s, championed the needs of the West, and was the organizer of a series of political compromises that kept the nation together before the Civil War. His economic ideas were dubbed the American System.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Interchangeable Parts: Pieced of a finished product that are standardized so that one piece could be swapped out for an identical replacement part. Before Eli Whitney made use of this system, everything was made by craftsmen and any broken piece required a hand-crafted replacement.

Corporation: A form of business in which investors are only liable up to the amount they invested.

Nativism: Belief that people born in a county are better than immigrants.

Textile Industry: The business of turning raw cotton into thread, then into cloth, and finally into finished products such as clothing.

![]()

CANALS, ROADS RAILROADS & BUSINESSES

Erie Canal: Canal that connected the Hudson River to the Great Lakes across New York State. It was completed in 1825 and helped establish New York City as the financial capital of nation and allowed New Englanders to easily settle the Midwest.

Cumberland Road: A federally-funded road that connected Maryland and Illinois. It was a project built as part of Henry Clay’s American system in the early 1800s.

Chesapeake and Ohio Canal: Canal connecting Washington, DC and Ohio. It was a project funded in party of Henry Clay’s American system in the early 1800s.

Baltimore and Ohio Railroad: First major railroad company in the United States.

Western Union: Major American telegraph company.

![]()

EVENTS

Industrial Revolution: A long, gradual change in both Europe and America away from small-scale production based on human and horsepower toward the use of machines, factories, and steam/coal power.

Market Revolution: A shift in the way Americans produced and consumed products. Over the course of the early 1800s, improvements in transportation and communication made it possible to originate a produce in one place and then move it far away to sell. This was a major shift away from subsistence farming.

Great Irish Potato Famine: A massive famine in Ireland between 1845 and 1849 that drove waves of immigration of impoverished Irish to America.

![]()

LAWS & POLICIES

American System: Henry Clay’s economic proposals. These included a protective tariff, a national bank, and federally-funded internal improvements such as canals and railroads.

Tariff of Abominations: Tariff passed in 1828 under John Quincy Adams. It was part of Henry Clay’s American System but disproportionately favored northern manufacturers and hurt southern consumers.

When Adams enacted a high tariff, what actions did the opposition take? Was there any violence?

How long did it take to create a canal compared to a railroad and how did they make it so that travelling up stream with doors was possible with the technology they had?

Whoever made child labor is sorta dumb like how could you trust children that much you would allow them to work for you. Even if they worked for a lower pay I would never trust children to make my products. So would you trust children in making stuff for your factory?

What was it that made religious leaders feel that it was sacreligious to them, as if religon had anything to do with messing with their beliefs?

If there is heavy rainfall, would the canals be affected?

What if America was full of yeoman farmers and no factories? Would we still have a market revolution?

What types of goods did the South get imported?

If I were to be living during the time of the Industrial revolution I would feel grateful because of how convenient it was but I can see why others would want to keep it the way it was because it does change the idea that you have to work for yourself to sustain your living.

Would there have been more yeoman farmers if plows were not invented?

As immigrants from Ireland and Germany pour into America, were there any immigrants that came from other countries such as Asia?

If the way that immigrants were treated was horrible how many of them decided to leave the US and move back to their country when they felt that things were of a better condition there?

How was life as a mill girl?

Did inventors ever have issues with other people stealing their ideas or products?

How did the Industrial revolution change the way on how people relied on themselves for survival?

How did Thomas Jefferson feel during the industrial revolution?

A connection that I see is how the people in North America reacted to newcomers in different times. When the Germans and Irish came to the US, they felt threatened politically and economically. They did not want these Europeans to immigrate and wanted to make it harder for them to gain citizenship. I find this hypocritical because the original colonists, who were mostly European immigrants themselves, were the very ones who also took over Native American lands. US citizens were just now experiencing the very struggle they put Native Americans through.

Why isn’t Erie Canal named after Dewitt Clinton? Why did they choose to name it the “Erie” Canal?

Considering that some first buildings or inventions were named after whoever founded it , Why Wasnt Eerie Canal named after its creator, Dewitt Clinton, and instead where did it come from ?

Is there any favoritism to any part of America now or are we all treated the same?

Why did the American’s all of a sudden pounce on the Irish and Germans on their religion? Wasn’t there the first amendment around at this time?

Did people from the south move to the North to get their thoughts heard or possibly favored?

In the reading it says that few other places besides US allowed German immigration. Why did other places not allow German immigration and why did US allow it?

Railroads have become so convenient for people to transport goods from one place to another. On the other hand, do you think there were people that preferred using canals more because it was the very first method of transporting goods? Thinking about it as preferring “older ways.”

In my opinion, people prefer using one over the other depending on what’s more convenient for them. I don’t think anyone would’ve preferred the canals over the railroads because railroads were a lot more efficient and cheaper.

If the Irish and Germans received such harsh punishments, why didn’t they fight back? Why did they flee all the way to the United States when they could’ve fought back and possibly win against their troubles?

I think that they thought the United States was their best option out of the few choices they had. They seemed desperate to leave their homes because of the hardships, and there were companies in the United States that needed workers. They could have possibly fought back, but they traveled a long way and probably did not want to further upset the Americans.

Were the Irish and Germans ever open about their political and religious views even though the government restricted them from it?

I think the Irish and Germans subconsciously understood that if they were to speak about their political and religious views, there was possibility that negative reactions would occur especially since the government restricted it. Knowing this, I believe most of them decided it was best to remain silent as speaking out could lead to consequences.

In the reading, it mentioned that part of the reason why the Americans were so hostile towards the new immigrants was because many of them were Roman Catholic or of another religion. This connects to the idea where the Constitution states in its First Amendment that everyone in the US should have the right to practice his or her own religion, or no religion at all. Do you think this contradicts the Constitution’s words of having “free religion”? If everyone had their own right to follow their own religion, why couldn’t the Americans tolerate the immigrants’ religions? Or was this just another way for the Americans to hate on the immigrants because they “took” their jobs?

With the new industries that popped up, there needed to be labor to work for companies. When did labor laws and unions start to exist and what prompted them to be created?

How did the bulk of immigrants come at such a “perfect” time where the canals were just being built? Its almost as if it was destiny for them to come and ultimately be the catalyst for the industrial revolution!

I think immigrants had been stuck in their country being poor and wanted to escape but did not see any better places to move. After the canals were built, its made american industry to different levels and the country seemed to have more jobs, more opportunities for them so that’s why they moved to america.

It was mentioned above that during the periods of time where there where large amounts immigration from the Irish and Germans that there was opposition against these immigrants as some Americans felt threatened that these workers would replace them because they are willing to for almost nothing, how does this relate to current day politics and immigration, and the things are President have said about immigrants taking jobs from Americans.

What were the benefits of having unmarried young women work at Lowell mills? In other words, why were unmarried young women chosen to work in these textile mills? Was it because they provided cheap labor because they’re not married?

I think it was because Lowell wanted to avoid child labor, like Samuel Slater, who used child labor for his factory. And this also gave women a sense of independence they wanted.