INTRODUCTION

The United States underwent dramatic changes during the period of Democratic-Republican political leadership in the first decades of the 1800s. The growth into the West and conflicts with Native Americans nations and problems dealing with the European powers posed a fundamental challenge to the fragile new republic.

At the heart of foreign relations in the first decades of the early republic was the challenge of being taken seriously. Despite having won independence from Britain, the United States remained weak. Without the help of the Spanish, and especially the French, victory would probably not have been possible. Now that the War for Independence was over, Americans wanted to be treated and respected as an independent nation. For the Europeans, America was a pawn. For the British, there was no reason to think American might not in the future be retaken and folded back into their empire. Just because we know now that it didn’t happen, does not mean that everyone assumed the same thing at the time.

The fundamental question the Founding Generation had to grapple with was how to be taken seriously by their powerful neighbors.

DEALING WITH BRITAIN AND FRANCE

The French Revolution was not just a matter of political identity for Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. The United States was a small new country and it found itself in the midst of the dramatic escalation of political and military conflicts between Europe’s two superpowers.

President Washington wanted the United States to remain neutral, fearing that foreign alliances would limit American sovereignty and draw the nation into foreign conflicts. He declared American neutrality, breaking the terms of a 1778 treaty with France that had promised mutual assistance between the two countries. While France had aided the Americans during the American Revolution, America would not do the same for France.

Washington’s decision stemmed from his philosophical commitment to non-involvement in foreign affairs, but was also based upon pragmatic considerations. 90% of all American imports came from Britain and customs duties on these imports produced 90% of federal revenue. Without trade with Britain, the federal government would have no money.

Additionally, the conflict in Europe created an immense opportunity for Americans. Farmers, merchants, and ship owners all stood to profit from the long European war. With European manufacturers busying themselves with war, American manufacturers were able to develop without the usual competition from the British and French. The war stimulated a broad recovery of the American economy.

In the face of American neutrality that would continue a strong economic relationship with Great Britain, the French government sent Edmond Genet to the United States as a diplomatic envoy. Genet was instructed by his superiors in Paris to enlist American aid for the French Revolution even though Washington had established a clear policy of neutrality.

Since Washington had no intention of helping the French, Genet called for American privateers to harass British ships and opened up the French sugar islands in the Caribbean for free trade with American ships. Supporters of the French Revolution, as well as those who stood to benefit from the new lucrative trade opportunities, rallied to support Genet’s mission. Federalists saw him as a renegade who broke American laws by manipulating American merchants into violating the national policy of neutrality. The French superpower clearly showed to qualms about trying to force the hand of the new American republic.

Britain responded to the offer of French free trade by seizing American ships that they suspected of carrying French goods. While Americans saw this as a deep violation of their national sovereignty and right to trade as a neutral nation, the British dismissed American claims to free trade as merely war time profiteering with the enemy.

At the same time, the British continued to occupy forts in the American Northwest that were supposed to have been abandoned by the terms of the peace treaty of 1783. Not only did the British army still not surrender these strategic strongholds, but they also supplied Native Americans with goods and encouraged them to attack the United States from the west.

While France ignored American neutrality, the British engaged in covert and explicit acts of war. Washington needed to do something to resolve these problems and demonstrate American independence. He may have won on the battlefield at Yorktown, but he would also have to win a delicate diplomatic and political battle as well.

Washington sent John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, on a diplomatic mission to England. He negotiated an extremely broad agreement that dealt with issues from repaying pre-Revolutionary debts, to the British forts in the West, and the rights of free trade across the Atlantic. When it was announced, Jay’s Treaty proved to be enormously controversial.

Clearly, America lacked the strength to force powerful Britain to capitulate on key issues, so compromise was necessary to convince Britain to agree to American demands. As a result, the agreement largely strengthened American ties to Great Britain. Although it was quite favorable to the Americans, the treaty was predictably denounced by the growing Democratic-Republican Party. Jay became the victim of harsh public protests that included burning him in effigy. The controversial treaty passed the senate with the minimum number of votes even with Washington’s total commitment to its success.

By concluding the treaty with Britain, Washington was able to avoid open war, but probably accelerated the political divide at home. Jefferson, Madison and their supporters wanted the United States to support France, and Jay’s Treaty infuriated them.

PICKNEY’S TREATY

France and Britain were not the only European powers America had to contend with. During the Revolution, Spain had aided the American cause, but Spain had not been a party to the Treaty of Paris. That treaty between Britain and the United States had specified the boundary between West Florida and the newly independent United States at 31° north. However, in the companion treaty signed between Britain and Spain, West Florida was ceded to Spain without its boundaries being specified. The Spanish government assumed that the boundary was the same as in the 1763 agreement by which they had first given their territory in Florida to Britain, claimed that the northern boundary of West Florida was at the 32° 22′, the boundary established by Britain in 1764 after the Seven Years’ War. The now independent United States insisted that the boundary was at 31°, as specified in its Treaty of Paris with Britain.

President Washington sent Thomas Pinckney to Spain to negotiate a settlement. The Treaty of San Lorenzo, know better in the United States as Pinckney’s Treaty, was signed in 1795 and established intentions of friendship between the United States and Spain. It also defined the border between the United States and Spanish Florida, and guaranteed the United States navigation rights on the Mississippi River.

The treaty had both positive short-term and long-term effects. In the near term, Spain agreed to allow American ships to navigate along the full length of the Mississippi River and to dock and do business in New Orleans, which was controlled by Spain. This permission, known as the right of deposit, was essential for the development of the West, especially in that it allowed farmers in the Ohio Valley the ability to ship goods by water to the cities of the Atlantic Coast.

In the long term, the treaty defined the boundary between the United States and Spanish Florida, which remains the boundary between Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Florida. Even better, it kept the United States out of war with Spain. Secondary Source: Map

Secondary Source: Map

This map shows the area that was claimed by both the United States and Spain that was the subject of Pinckney’s Treaty.

THE XYZ AFFAIR AND QUASI-WAR WITH FRANCE

The second president, John Adams also faced a major international crisis. The French were outraged by what they viewed as an Anglo-American alliance in Jay’s Treaty. France suspended diplomatic relations with the United States at the end of 1796 and seized more than 300 American ships over the next two years.

Adams responded by sending a diplomatic mission to France. The diplomats, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, John Marshall, and Elbridge Gerry, were approached through informal channels by agents of the French Foreign Minister Talleyrand, who demanded bribes and a loan before formal negotiations could begin. Although such demands were not uncommon in mainland European diplomacy of the time, the Americans were offended by them, and eventually left France without ever engaging in formal negotiations.

While the American diplomats were in Europe, President Adams considered his options in the event of the commission’s failure. His cabinet urged that the nation’s military be strengthened, including the raising of a 20,000-man army and the acquisition or construction of ships for the navy. He had no substantive word from the commissioners until March 1798, when the first dispatches revealing the French demands and negotiating tactics arrived. The commission’s apparent failure was duly reported to Congress, although Adams kept French disrespect for the American emissaries and their demand of a bribe secret, seeking to minimize a warlike reaction.

His cabinet was divided on how to react. The general tenor was one of hostility toward France, with Attorney General Charles Lee and Secretary of State Timothy Pickering arguing for a declaration of war. Democratic-Republican leaders in Congress, believing Adams was pro-British and wanted war, united with hawkish Federalists to demand the release of the commissioners’ dispatches. On March 20, Adams turned them over, with the names of some of the French actors redacted and replaced by the letters W, X, Y, and Z. The use of these disguising letters led the business to immediately become known as the XYZ Affair.

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

A British cartoon depicting French diplomats abusing America, a woman with Native American feathers, while John Bull (Britain’s version of Uncle Sam) sits on a hill watching.

The release of the dispatches produced exactly the response Adams feared. Federalists called for war, and Democratic-Republicans, realizing that Adams was actually working for peace, but that the French had refused, were left without an effective argument. Despite calls for a formal war declaration, Adams steadfastly refused to ask Congress for one.

American popular support for France weakened dramatically as the Federalists effectively used the slogan “millions for defense, but not one cent for tribute” to strengthen their political position. Federalists who controlled the Congress as well as the presidency raised new taxes, dramatically enlarged the army and navy, and generally increased the power of the central government in preparation for a war against France that seemed inevitable.

The Adams Administration entered a quasi-war with France from 1798 to 1800. Although no official declaration of war had been made, the seizure of American ships by France was viewed by the Adams Administration as an act of war and the United States began acting as an unofficial ally of Great Britain. Only 15 years after the end of the Revolutionary War, a dramatic transition in American international alliances had occurred.

While France under the rule of a king had supported colonial America in its revolutionary fight against the British, republican America now joined with Britain, its former revolutionary enemy, to challenge republican France. In spite of this dramatic change, the French seizure of American ships incensed Americans and Adams’ anti-French policies were extremely popular.

Rather than continue to use the exigencies of war to build his own popularity and to justify the need for strong federal authority, Adams opened negotiations with France when the opportunity arose to work toward peace. Reconciling with France during the critical campaign of 1800 enraged many Federalists. Adams, however, preferred to see himself as president above the political fray, acting as a representative of the people in general.

While maintaining peace was good for the country, it was bad politics. Alexander Hamilton, Adams’ nemesis within the Federalist Party and ever the shrewd political operator, denounced Adams’ actions. A quasi-war clearly could stimulate patriotic fervor and might help Federalists win the upcoming election. In the end, Adams only convinced the Federalist Congress to move toward peace by threatening to resign and thus allow Jefferson to become president. Vilified by his political opponents and abandoned by his own party, Adams would be the only one-term president in the early national period until his son suffered the same fate in the election of 1828.

John Adams was a complex figure. A vain man who took offense easily, he also acted honorably in refusing to exploit war with France for personal and partisan gain. Such deeply principled actions marked his public career from its earliest days.

JEFFERSON AND THE BARBARY PIRATES

Thomas Jefferson has the dubious distinction of being the first president to send Americans into battle overseas. His target were the four nations along the Mediterranean coast of North Africa known as the Barbary States.

In fact, two wars were fought at different times between the United States and the Barbary States. At issue were demands by the Barbary leaders for tribute from American merchant vessels in the Mediterranean Sea. If ships failed to pay, pirates would attack the vessels and take their goods, often enslaving crew members or holding them for ransom.

In 1801, newly minted president Thomas Jefferson refused to pay the Barbary States a tribute, whereupon Yusuf Karamanli, the Pasha of Tripoli, declared war on the United States. In response, Jefferson sent a naval fleet to the Mediterranean. Throughout the war, the navy bombarded various fortified cities along the coast and maintained a blockade in Tripoli’s harbor. After a stunning defeat at Tripoli and wearied from the blockade and raids, Yussif Karamanli signed a treaty ending hostilities on June 10, 1805, and the United States was given fair passage through the Mediterranean.

Seven years later, the Barbary States again initiated piracy against American ships, and again the navy was dispatched to the Mediterranean to fight. This time under President Madison and once again the Barbary leaders were forced to capitulate and recognize the right of American ships to pass unimpeded through the Mediterranean.

Although relatively unknown today, the war against the Barbary Pirates was an important initial success for the fledgling American navy. It is best remembered now as a line in the Marine’s Hymn: “From the Halls of Montezuma, To the shores of Tripoli; We fight our country’s battles, In the air, on land, and sea…” Primary Source: Painting

Primary Source: Painting

A contemporary rendition of the clash between American and Barbary ships in the Mediterranean Sea.

THE EMBARGO OF 1807

Despite their best efforts, the first presidents were unable to maintain American neutrality. In 1812, the nation again went to war, and once again with Britain. Some historians see the conflict as a Second War for American Independence.

The three-year war marks a traditional boundary between the early republic and early national periods. The former period had strong ties to the more hierarchical colonial world of the 1700s, while post-war developments moved the nation in dynamic new directions that contributed to a more autonomous American society and culture. Although the War of 1812 serves as an important turning point in the development of an independent United States, the war itself was mostly a political and military disaster for the country.

By 1812 the wars in Europe had taken a different turn. The French Revolution was over and France was now led by the brilliant military strategist Napoleon Bonaparte. However, as had also been true in the 1790s, neither European superpower respected the neutrality of the United States. Instead, both tried to prevent American ships from carrying goods to their enemy. Both Britain and France imposed blockades to limit American merchants, though the dominant British navy was more successful.

In response to this denial of American sovereignty, President Jefferson and his secretary of state James Madison crafted an imaginative, but fundamentally flawed, policy of economic coercion. Their Embargo of 1807 banned American ships from any trade with Europe in the belief that dependence on American goods would soon force France and Britain to honor American neutrality. The plan backfired, however, as the Democratic-Republican leaders failed to understand how deeply committed the superpowers were to carrying on their war despite its high costs.

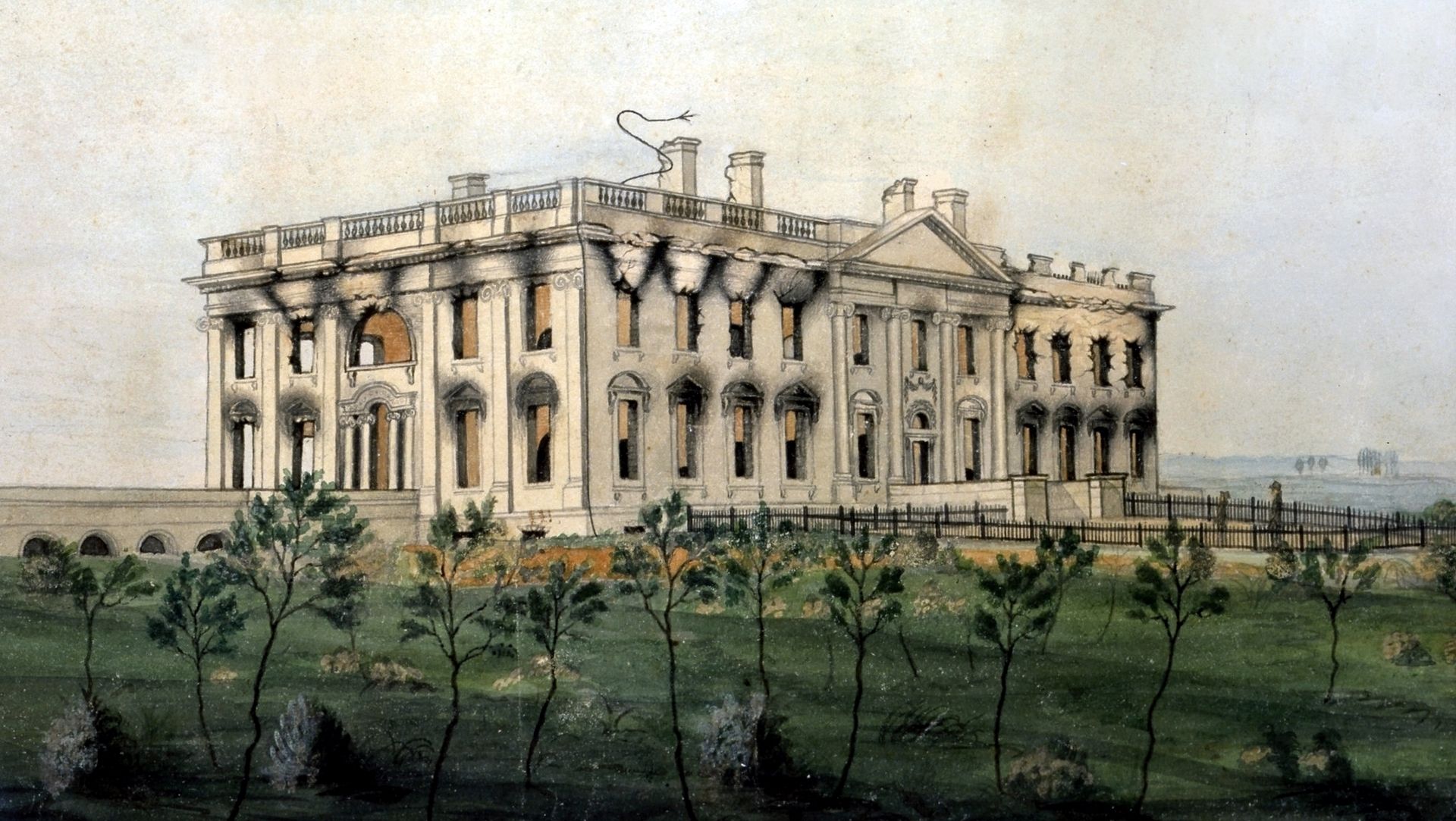

The Embargo not only failed diplomatically, but also caused enormous domestic dissent. American shippers, who were primarily concentrated in Federalist New England, generally circumvented the unpopular law. Its toll was clearly marked in the sharp decline of American imports from 108 million dollars’ worth of goods in 1806 to just 22 million in 1808. This unsuccessful diplomatic strategy that mostly punished Americans helped to spur a Federalist revival in the elections of 1808 and 1812. Nevertheless, Republicans from Virginia continued to hold the presidency as James Madison replaced Jefferson in 1808. Primary Source: Painting

Primary Source: Painting

The burned out shell of the White House after the attack by the British.

THE WAR OF 1812

Madison faced difficult circumstances in office with increasing Native American violence in the West and war-like conditions on the Atlantic. These combined to push him away from his policy of economic coercion toward an outright declaration of war. This intensification was favored by a group of pro-war Westerners and Southerners in Congress led by Henry Clay of Kentucky and nicknamed the War Hawks.

Perhaps most infuriating for the American public, however, was the issue of impressment. Britain claimed the right to take any British sailors serving on American merchant ships. In practice, the British stopped American ships and took anyone they wanted, claiming they were British, and forced them to serve on British ships. This was nothing short of kidnapping.

Most historians now agree that the War of 1812 was “a western war with eastern labels.” By this, they mean that the real causes of the war stemmed from desire for control of western Native Americans lands and clear access to trade through New Orleans. While the issue of national sovereignty, so clearly denied by British rejection of American free trade on the Atlantic and impressment, provided a more honorable rationale for war.

Even with the intense pressure of the War Hawks, the United States entered the war hesitantly and with especially strong opposition from Federalist New England who would stand to lose business in a war with their primary trading partner. When Congress declared war in June 1812, its heavily divided votes (19 to 13 in the Senate and 79 to 49 in the House) suggest that the republic entered the war as a divided nation.

America’s initial invasion of Canada which was still part of the British Empire in the summer of 1812 was repulsed by the British and their Native Americans allies under the leadership of Tecumseh. Although Tecumseh would be killed in battle the following fall, American was unable to mount a major invasion of Canada because of significant domestic discord over war policy. Most importantly, the governors of most New England states refused to allow their state militias to join a campaign beyond state boundaries. Similarly, a promising young Congressman from New Hampshire, Daniel Webster, actually discouraged enlistment in the army.

One bright spot for the Americans was Oliver Hazard Perry’s destruction of the British fleet on Lake Erie in September 1813 that forced the British to flee from Detroit. Primary Source; Painting

Primary Source; Painting

An artist’s impression of the bombardment of Fort McHenry guarding Baltimore Harbor by the British fleet. The survival of the fort inspired Francis Scott Key to write the poem that became The Star-Spangled Banner.

Minor victories aside, things looked bleak for the Americans in 1814. With Napoleon’s French forces failing in Europe, Britain committed more of its resources to the American war and in August sailed up the Potomac River to occupy Washington, DC and burn the White House. President Madison had to flee the city. His wife Dolley gathered invaluable national objects, including Gilbert Stuart’s portrait of George Washington, and escaped with them at the last minute. It was the nadir of the war.

On the edge of national bankruptcy and with the capital largely in ashes, total American disaster was averted when the British failed to capture Fort McHenry that protected nearby Baltimore. Watching the failed attack on Fort McHenry as a prisoner of the British, Francis Scott Key wrote a poem later called “The Star-Spangled Banner” which was set to the tune of an English drinking song. It became the official national anthem of the United States of America in 1931.

THE HARTFORD CONVENTION

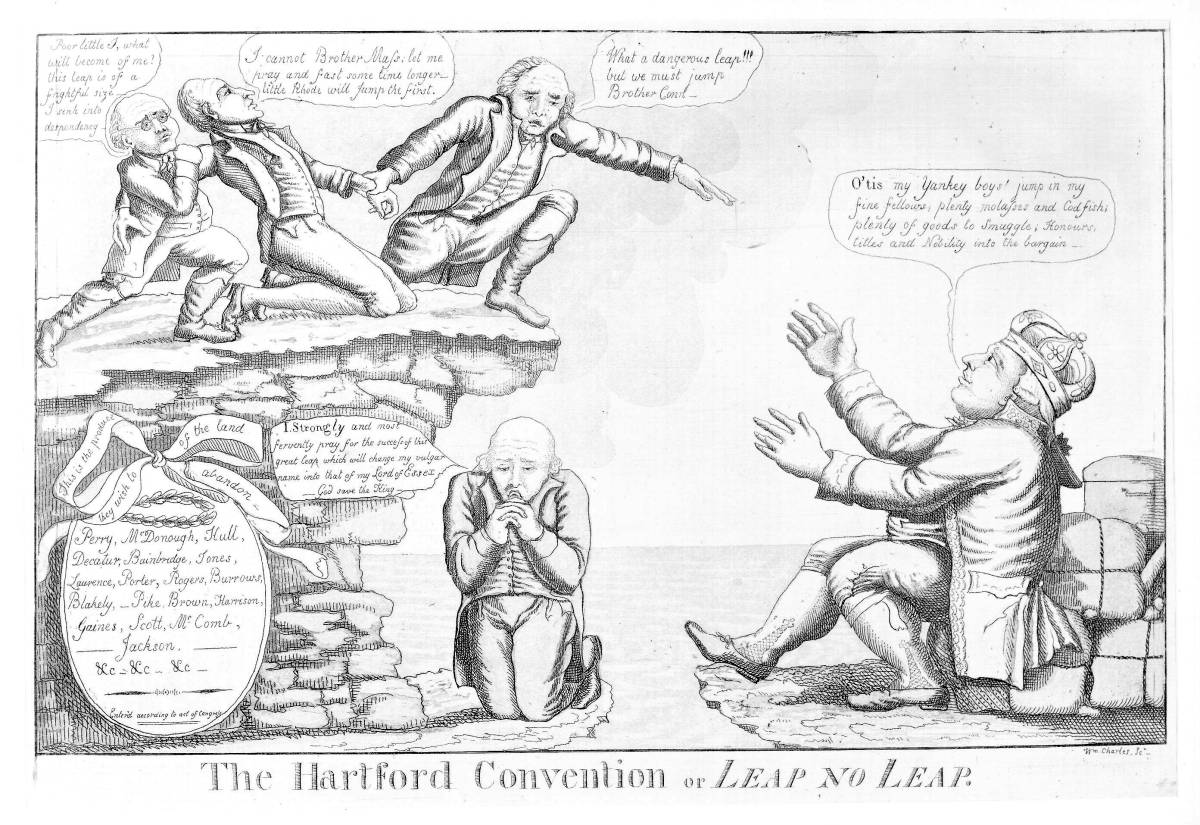

The most critical moment of the War of 1812, however, may not have been a battle, but rather a political meeting called by the Massachusetts legislature. Beginning in December 1814, 26 Federalists representing New England states met at the Hartford Convention to discuss how to reverse the decline of their party and the region. Although manufacturing was booming and contraband trade brought riches to the region, war and its expenses proved hard to swallow for New Englanders.

Federalist New England’s opposition to national policies had been demonstrated in numerous ways from circumventing trade restrictions as early as 1807, to voting against the initial declaration of war in 1812, refusing to contribute state militia to the national army, and now its representatives were moving on a dangerous course of semi-autonomy during war time. Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

A cartoon ridiculing the Federalists who are depicted blindly leaping into the arms of a waiting British monarch.

Although it probably would have hurt them in the end, the angry Federalists who met in Hartford discussed various possibilities such as expelling the western states, succeeding and negotiating their own peace treaty with Britain,

If a peace treaty ending the War of 1812 had not been signed while the Hartford Convention was still meeting, New England may have seriously debated seceding from the Union. Other more down-to-earth suggestions were made such as ending the unpopular embargo, limiting presidents to two terms, requiring a 2/3 majority vote for a declaration of war and mandating that a president be from a different state than his predecessor. After all, three out of the four presidents up to that date had been Virginians.

The Federalists had terrible timing. Just as news of their ideas leaked out, Andrew Jackson and his American army won a stunning victory in New Orleans and Madison concluded a peace treaty ending the war. The combined effect was that the Federalists became synonymous with disunion, secession, and treason, especially in the South. The party was ruined, and ceased to be a significant force in national politics.

EFFECTS OF THE WAR OF 1812

The War of 1812 came to an end largely because the British public had grown tired of the sacrifice and expense of their twenty-year war against France. Now that Napoleon was all but finally defeated, the minor war against the United States in North America lost popular support. Negotiations began in August 1814 and on Christmas Eve the Treaty of Ghent was signed in Belgium. The treaty called for the mutual restoration of territory based on pre-war boundaries and with the European war now over, the issue of American neutrality had no significance.

In effect, the treaty did not change anything and hardly justified three years of war and the deep divide in American politics that it exacerbated. Secondary Source: Painting

Secondary Source: Painting

An artist’s rendition of Andrew Jackson leading the American forces at the Battle of New Orleans. This was painted after the event, and probably does not depict the battle as it really happened.

Popular memory of the War of 1812 might have been quite so dour had it not been for a major victory won by American forces at New Orleans on January 8, 1815. Although the peace treaty had already been signed, news of it had not yet arrived on the battlefront where General Andrew Jackson led a decisive victory resulting in 700 British casualties versus only 13 American deaths. Of course, the Battle of New Orleans had no military or diplomatic significance, but it did allow Americans to swagger with the claim of a great win.

Furthermore, the victory launched the public career of Andrew Jackson as a new kind of American leader totally different from those who had guided the nation through the Revolution and early republic. The Battle of New Orleans vaunted Jackson to heroic status and he became a symbol of the new American nation emerging in the early 19th Century.

CONCLUSION

Foreign relations in the early republic period war messy. Washington warned against foreign entanglements in his Farewell Address, and Adams and Jefferson both did their best to avoid unnecessary alliances, but powerful neighbors forced their hands.

The XYZ Affair illustrates quite clearly just how insignificant Americans were on the world stage, at least in the view of the European powers. So, how can a weak nation gain the respect of powerful neighbors?

Is war essential? That is what happened in 1812.

What do you think?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The young United States was often caught between the warring powers of Britain and France. American leaders had different ideas about who to support and often found themselves in conflicts they would rather have avoided. In the end, America fought a second war with Britain.

In its early years, the United States had problems with both Britain and France. These were the two most powerful European powers and were in conflict with one another. Americans wanted to do business and benefit from this war but had problems maintaining independence from foreign influence.

Britain continued to maintain forts in American territory in the West that they had promised to leave after the Revolution. They actively encouraged and supported Native Americans who opposed American expansion. The British navy impressed American sailors. To solve these problems, America negotiated Jay’s Treaty. In return the United States agreed to pay back debts to British banks from before the Revolution. Democratic-Republicans saw this as giving in to the British.

America also negotiated Pinckney’s Treaty with Spain to gain land in what is now Mississippi and Alabama and the right to carry out trade in New Orleans.

American diplomats were disrespected by French officials embarrassing John Adams. The result was a non-declared war with France as the French navy tried to stop Americans from trading with Britain.

President Jefferson sent the navy to the Mediterranean Sea to fight the pirates from the Barbary States of North Africa.

Jefferson also implemented an embargo against both British and French imports in an attempt to stop them from interfering with American shipping, but the embargo simply hurt business and was unpopular.

America ultimately fought a declared war against Britain in 1812. Impressment of American sailors and British support for Native Americans in the West led Congress to declare war. It was not universally popular in Congress or with the public. The United States invaded Canada, but it did not go well. British troops bombarded Fort McHenry in Baltimore, an event that was immortalized in The Star-Spangled Banner, and burned Washington, DC. The United States had some minor victories as well, including a decisive victory by Andrew Jackson’s troops in New Orleans.

The War of 1812 led to the demise of the Federalist Party. At their convention in Hartford, talk turned to secession of New England. The war had been unpopular in New England since it was a center of trade with Britain. For most Americans, talk of secession simply sounded unpatriotic. Never again were the Federalists a force in national politics.

The War of 1812 concluded in a stalemate. The two sides agreed to the pre-war borders, so no land was exchanged. The Americans confirmed their independence and Andrew Jackson launched his political career.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

War Hawks: Young members of congress in 1812 who advocated for war with Britain. They were led by Kentuckian Henry Clay.

Francis Scott Key: American lawyer who wrote The Star-Spangled Banner during the War of 1812.

Andrew Jackson: American hero of the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812, and later president.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Right of Deposit: Permission to stop and do business in a foreign port. This was an important element of Pinckney’s Treaty when Spain granted it to American farmers transporting crops along the Mississippi River.

Impressment: Forcing American sailors to serve on British ships. This was one cause of the War of 1812.

![]()

SONGS

The Star-Spangled Banner: The national anthem. They lyrics were written by Frances Scott Key during the War of 1812.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Barbary States: A series of kingdoms along the Mediterranean Coast of Africa. They preyed on merchant ships demanding tribute for safe passage. Presidents Jefferson and Madison both sent the navy to fight them.

![]()

EVENTS

XYZ Affair: Political scandal during the John Adams administration when letters from American diplomats in France were made public detailing an effort by France’s foreign minister to demand bribes from the Americans.

Quasi-War with France: Open conflict with France from 1798 to 1800 on the high seas due to American neutrality. France was attempting to stop American merchants from doing business with Britain. No declaration of war was ever made.

First Barbary War: Naval conflict in the Mediterranean Sea between America and the Barbary Pirates in 1801 during Thomas Jefferson’s presidency.

Second Barbary War: Naval conflict in the Mediterranean Sea between America and the Barbary Pirates in 1807 during James Madison’s presidency.

Embargo of 1807: Embargo on imports from Europe established by President Jefferson in an effort to stop French and British ships from attacking American merchants. The plan backfired as it hurt Americans more than Europeans.

War of 1812: War with Britain. It was America’s first declared war. It lasted three years and resulted in a military stalemate, but affirmed American independence and provided renewed sense of national identity.

British attack on Washington, DC: 1814 attack during the War of 1812 by the British on the nation’s capital in which they burned the White House, Capitol and other government buildings.

Hartford Convention: Meeting of Federalists in 1814 in which secession of the New England States was discussed. It led to the downfall of the party as a force in national politics.

Battle of New Orleans: Final battle of the War of 1812. It was actually fought after the Treaty of Ghent had been signed, but before the news of the treaty had arrived. The stunning American victory propelled Andrew Jackson to national popularity.

![]()

TREATIES

Jay’s Treaty: 1794 treaty with Britain resolving problems after the Revolution. America agreed to pay debts owed to Britain and Britain agreed to leave forts it occupied in the West. It was hated by Democratic-Republicans who saw the treaty as overly pro-Britain and anti-French.

Pinckney’s Treaty: 1795 treaty with Spain resolving a border dispute between the border of the United States and Spanish Florida. It also guaranteed the United States navigation rights on the Mississippi River and the Right of Deposit in Spanish New Orleans.

Treaty of Ghent: Treaty that ended the War of 1812. It reaffirmed American independence but otherwise resulted in no significant changes.