TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

In the previous unit, we explored the American Revolution and accurately celebrated the amazing changes it brought to both the nation and the world. A new nation was born, as was an admirable tradition of rejecting tyranny in favor of representative government. Enlightenment ideals were lifted out of the pages of philosophy and made real on the battlefield.

School children have, for centuries, been indoctrinated with a love for the brave Founding Fathers who put their names to the Declaration of Independence and across the nation we celebrate that important day with barbeques, pool parties and fireworks. However, there is not universal acceptance of the glorified view of the Revolution.

For many Americans, life after the Revolution remained mostly unchanged, or even worse. The Revolution may have swept out British authority, but the seats of power were replaced by wealthy, White men of property. Basic liberties were not guaranteed, and Native Americans suffered far more at the hands of White Americans than they had under British rule.

From the most cynical viewpoint, the Founders were wealthy men who stood to lose under the economic structures of mercantilism and British taxation so they manipulated the public into supporting a war so they could usurp power.

Of course, such a view ignores the idealism of the Revolution and all those who have drawn inspiration from it, but it is worth looking at the outcome of the Revolution for different groups of Americans and asking ourselves just how revolutionary things were for them.

Ask yourself: Was the American Revolution actually revolutionary?

THE MEANING OF THE DECLARATION

“When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.”

So begins the Declaration of Independence. But what was the Declaration? Why do Americans continue to celebrate its public announcement as the birthday of the United States, July 4, 1776? While that date might just mean a barbecue and fireworks to some today, what did the Declaration mean when it was written in the summer of 1776?

On one hand, the Declaration was a formal legal document that announced to the world the reasons that led the thirteen colonies to separate from the British Empire. Much of the Declaration sets forth a list of abuses that were blamed on King George III. One charge levied against the King sounds like a Biblical plague: “He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance.”

The Declaration was not only legalistic, but practical too. Americans hoped to get financial or military support from other countries that were traditional enemies of the British. However, these legal and pragmatic purposes, which make up the bulk of the actual document, are not why the Declaration is remembered today as a foremost expression of the ideals of the Revolution.

The Declaration’s most famous sentence reads, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Even today, this inspirational language expresses a profound commitment to human equality.

This ideal of equality has certainly influenced the course of American history. Early women’s rights activists at Seneca Falls in 1848 modeled their Declaration of Sentiments in precisely the same terms as the Declaration of Independence. “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” they said, “that all men and women are created equal.” Similarly, the African-American anti-slavery activist David Walker challenged white Americans in 1829 to “See your Declaration Americans!!! Do you understand your own language?” Walker dared America to live up to its self-proclaimed ideals. If all men were created equal, then why was slavery legal?

The ideal of full human equality has been a major legacy, and ongoing challenge, of the Declaration of Independence. But the signers of 1776 did not have quite that radical an agenda. The possibility for sweeping social changes was certainly discussed in 1776. For instance, Abigail Adams suggested to her husband John Adams that in the “new Code of Laws” that he helped draft at the Continental Congress, he should, “Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them.” It didn’t work out that way.

Thomas Jefferson provides the classic example of the contradictions of the Revolutionary Era. Although he was the chief author of the Declaration, he also owned slaves, as did many of his fellow signers. They did not see full human equality as a positive social goal. Nevertheless, Jefferson was prepared to criticize slavery much more directly than most of his colleagues. His original draft of the Declaration included a long passage that condemned King George for allowing the slave trade to flourish. This implied criticism of slavery, a central institution in early American society, was deleted by just one vote of the Continental Congress before the delegates signed the Declaration. Primary Source: Document

Primary Source: Document

The Declaration of Independence. This signed copy is considered the official version and is now on view at the National Archives in Washington, DC.

So, what did the signers intend by using such idealistic language? Look at what follows the line, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.”

These lines suggest that the whole purpose of government is to secure the people’s rights and that government gets its power from “the consent of the governed.” If that consent is betrayed, then “it is the right of the people to alter or abolish” their government. When the Declaration was written, this was a radical statement. The idea that the people could reject a monarchy, and replace it with a republican government based on the consent of the people was a revolutionary change.

Historians must be careful to balance the meaning of events in their own time and the meaning they have taken on over time. The sentiments expressed in the Declaration of Independence are enormously important now. However, the generation of Americans who secured independence did not share the same ideas about equality we associate with the Declaration. The fact was that for many people in America, very little changed because of the Revolution.

THE SOLDIERS

Americans remember the famous battles of the American Revolution such as Bunker Hill, Saratoga, and Yorktown, in part, because they were Patriot victories. But this apparent string of successes is misleading.

The Patriots lost more battles than they won and, like any war, the Revolution was filled with hard times, loss of life, and suffering. In fact, the Revolution had one of the highest casualty rates of any American war. Only the Civil War was bloodier.

In the early days of 1776, most Americans were naïve when assessing just how difficult the war would be. Great initial enthusiasm led many men to join local militias where they often served under officers of their own choosing. Yet, these volunteer forces were not strong enough to defeat the British army, which was the most highly trained and best equipped in the world. Because most men preferred serving in the militia, the Continental Congress had trouble getting volunteers for General George Washington’s Continental Army. This was in part because, the Continental Army demanded longer terms and harsher discipline.

Washington correctly insisted on having a regular army as essential to any chance for victory. After a number of militia losses in battle, the Congress gradually developed a stricter military policy. It required each state to provide a larger quota of men, who would serve for longer terms, but who would be compensated by a signing bonus and the promise of free land after the war. This policy aimed to fill the ranks of the Continental Army, but was never entirely successful. While the Congress authorized an army of 75,000, at its peak Washington’s main force never had more than 18,000 men. The terms of service were such that only men with relatively few other options chose to join the Continental Army.

Part of the difficulty in raising a large and permanent fighting force was that many Americans feared the army as a threat to the liberty of the new republic. The ideals of the Revolution suggested that the militia, made up of local Patriotic volunteers, should be enough to win in a good cause against a corrupt enemy. Beyond this idealistic opposition to the army, there were also more pragmatic difficulties. If a wartime army camped near private homes, they often seized food and personal property. Exacerbating the situation was Congress inability to pay, feed, and equip the army.

As a result, soldiers often resented civilians whom they saw as not sharing equally in the sacrifices of the Revolution. Several mutinies occurred toward the end of the war, with ordinary soldiers protesting their lack of pay and poor conditions. Not only were soldiers angry, but officers also felt that the country did not treat them well. Patriotic civilians and the Congress expected officers, who were mostly elite gentlemen, to be honorably self-sacrificing in their wartime service. When officers were denied a lifetime pension at the end of the war, some of them threatened to conspire against the Congress. General Washington, however, acted swiftly to halt this threat before it was put into action.

The Continental Army defeated the British, with the crucial help of French financial and military support, but the war ended with very mixed feelings about the usefulness of the army. Not only were civilians and those serving in the military mutually suspicious, but also even within the army soldiers and officers could harbor deep grudges against one another. The war against the British ended with the Patriot military victory at Yorktown in 1781. However, the meaning and consequences of the Revolution had not yet been decided.

THE LOYALISTS

Any full assessment of the American Revolution must try to understand the place of Loyalists, those Americans who remained faithful to the British Empire during the war.

Although Loyalists were steadfast in their commitment to remain within the British Empire, it was a very hard decision to make and to stick to during the Revolution. Even before the war started, a group of Philadelphia Quakers were arrested and imprisoned in Virginia because of their perceived support of the British. The Patriots were not a tolerant group, and Loyalists suffered regular harassment, had their property seized, or were subject to personal attacks.

The process of tar and feathering, for example, was brutally violent. Stripped of clothes, covered with hot tar, and splattered with feathers, the victim was then forced to parade about in public. Unless the British Army was close at hand to protect Loyalists, they often suffered at the hands of local Patriots and often had to flee their own homes. About one-in-six Americans was an active Loyalist during the Revolution, and that number undoubtedly would have been higher if the Patriots hadn’t been so successful in threatening and punishing people who made their Loyalist sympathies known.

One famous Loyalist is Thomas Hutchinson, a leading Boston merchant from an old American family, who served as governor of Massachusetts. Viewed as pro-British by some citizens of Boston, Hutchinson’s house was burned in 1765 by an angry crowd protesting the Crown’s policies. In 1774, Hutchinson left America for London where he died in 1780 and always felt exiled from his American homeland. One of his letters suggested his sad end, for he, “had rather die in a little country farm-house in New England than in the best nobleman’s seat in old England.” Like his ancestor, Anne Hutchinson who suffered religious persecution from Puritan authorities in the early 17th-century, the Hutchinson family suffered severe punishment for holding beliefs that other Americans rejected.

Perhaps the most interesting group of Loyalists were enslaved African-Americans who chose to join the British army. The British promised to liberate slaves who fled from their Patriot masters. This powerful incentive, and the opportunities opened by the chaos of war, led some 50,000 slaves (about 10 percent of the total slave population in the 1770s) to flee. When the war ended, the British evacuated 20,000 formerly enslaved African Americans and resettled them as free people.

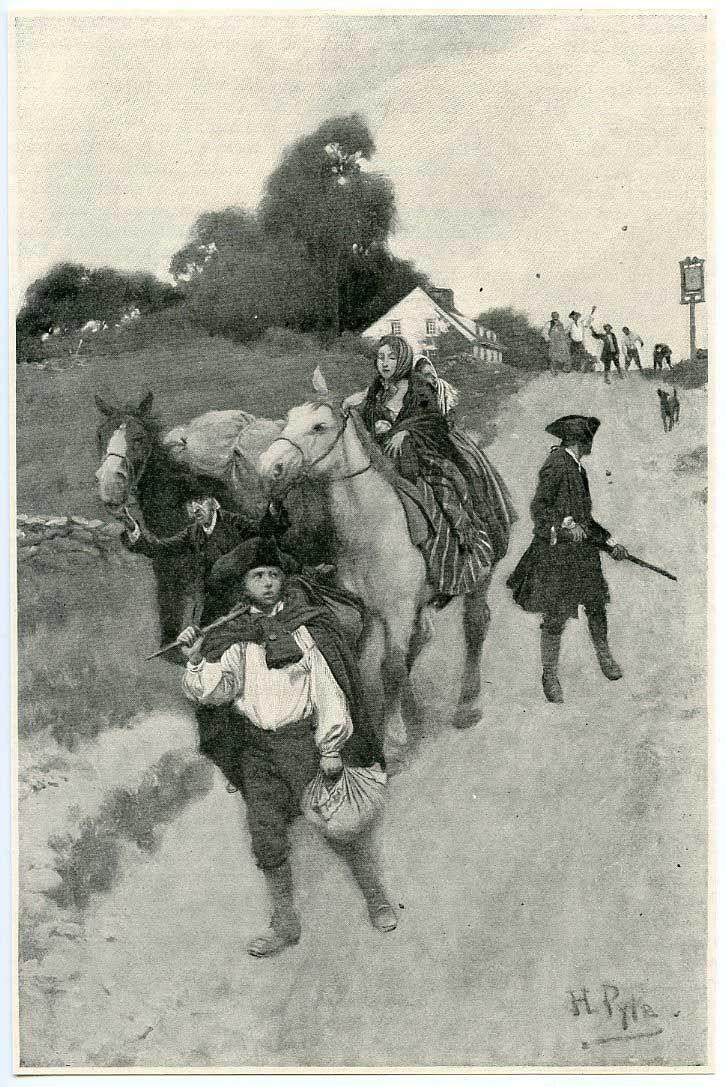

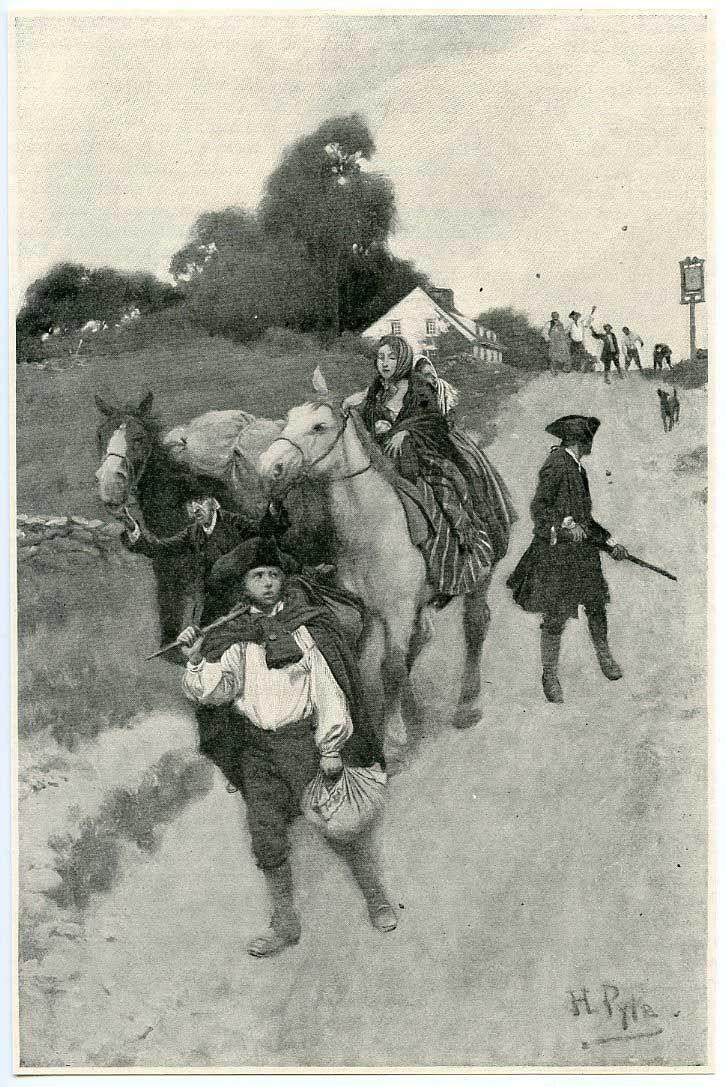

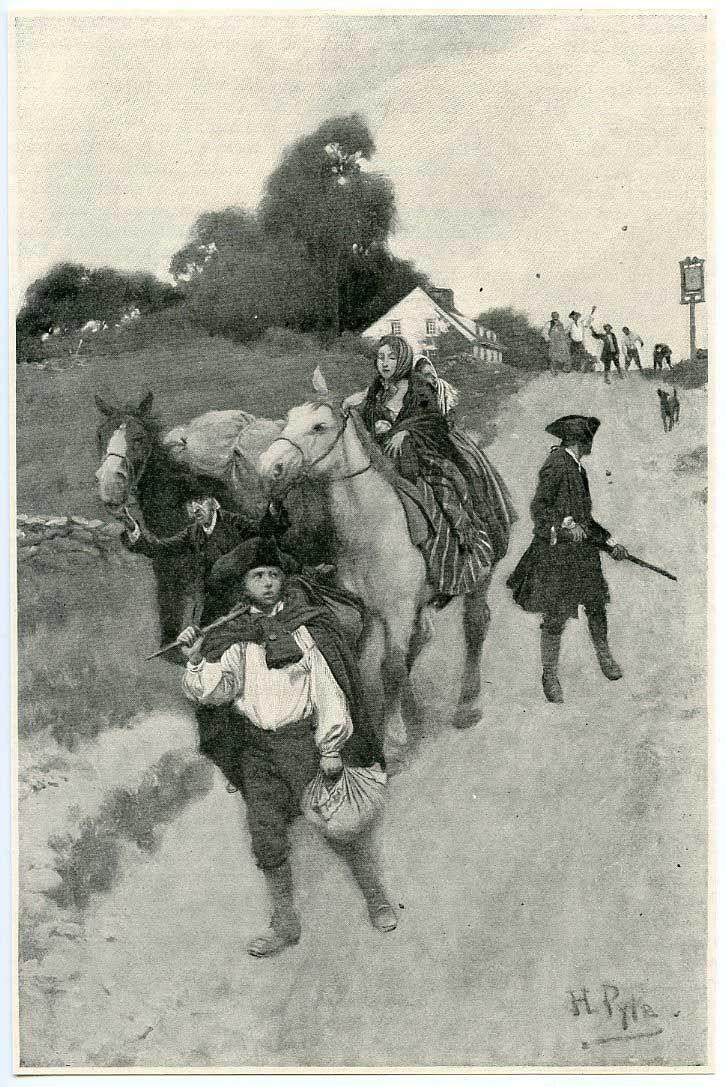

Along with this group of black Loyalists, about 80,000 other Loyalists chose to leave the independent United States after the Patriot victory in order to remain members of the British Empire. Wealthy men like Thomas Hutchinson who had the resources went to London. But most ordinary Loyalists went to Canada where they would come to play a large role in the development of Canadian society and government. In this way, the American Revolution played a central role shaping the future of two North American countries. Secondary Source: Sketch

Secondary Source: Sketch

Tory Refugees on their way to Canada, a sketch by American artist Howard Pyle. The work appeared in Harper’s Monthly in December 1901.

AFRICAN AMERICANS

The American Revolution, as an anti-tax movement, centered on Americans’ right to control their own property. In the 18th century “property” included other human beings.

In many ways, the Revolution reinforced American commitment to slavery. On the other hand, the Revolution also hinged on radical new ideas about “liberty” and “equality,” which challenged slavery’s long tradition of extreme human inequality. The changes to slavery in the Revolutionary Era revealed both the potential for radical change and its failure more clearly than any other issue. Secondary Source: Engraving

Secondary Source: Engraving

Bishop Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church

Slavery was a central institution in American society during the late-18th century, and was accepted as normal and applauded as a positive thing by many white Americans. However, this broad acceptance of slavery among the White population began to be challenged in the Revolutionary Era. The challenge came from several sources, partly from Revolutionary ideals, partly from a new evangelical religious commitment that stressed the equality of all Christians, and partly from a decline in the profitability of tobacco in the most significant slave region of Virginia and adjoining states.

The decline of slavery in the period was most noticeable in the states north of Delaware, all of which passed laws outlawing slavery quite soon after the end of the war. However, these gradual emancipation laws were very slow to take effect. Many of them only freed the children of current slaves, and even then, only when the children turned 25 years old. Although laws prohibited slavery in much of the North, slavery persisted well into the 19th century.

Even in the South, there was a significant movement toward freeing slaves. In states where tobacco production no longer demanded large numbers of slaves, the free black population grew rapidly. By 1810, one third of the African American population in Maryland was free, and in Delaware, free blacks outnumbered enslaved African Americans by three to one. Even in the powerful slave state of Virginia, the free black population grew more rapidly than ever before in the 1780s and 1790s. This new free black population created a range of public institutions for themselves that usually used the word “African” to announce their distinctive pride and insistence on equality.

The most famous of these new institutions was Richard Allen’s African Methodist Episcopal Church founded in Philadelphia.

Although the rise of the free black population is one of the most notable achievements of the Revolutionary Era, it is crucial to note that the overall impact of the Revolution on slavery also had negative consequences. In rice-growing regions of South Carolina and Georgia, the Patriot victory confirmed the power of the master class. Doubts about slavery and legal modifications that occurred in the North and Upper South, never took serious hold among whites in the Lower South. Even in Virginia, the move toward freeing slaves was made more difficult by new legal restrictions in 1792.

In the North, where slavery was on its way out, racism still persisted, as in a Massachusetts law of 1786 that prohibited whites from legally marrying African Americans, Native Americans, or people of mixed race. The Revolution clearly had a mixed impact on slavery and contradictory meanings for African Americans.

WOMEN

The Revolutionary rethinking of the rules for society also led to some reconsideration of the relationship between men and women. At this time, women were widely considered inferior to men, a status that was especially clear in the lack of legal rights for married women. Laws did not recognize wives’ independence in economic, political, or civic matters in Anglo-American society of the eighteenth century.

Even future first ladies had relatively little influence. After the death of her first husband, Dolley Todd Madison, had to fight her deceased spouse’s heirs for control of his estate. And Abigail Adams, an early advocate of women’s rights, could only encourage her husband John, to “remember the ladies” when drawing up a new federal government. She could not participate in the creation of this government herself.

The Revolution increased people’s attention to political matters and made issues of liberty and equality especially important. As Eliza Wilkinson of South Carolina explained in 1783, “I won’t have it thought that because we are the weaker sex as to bodily strength we are capable of nothing more than domestic concerns. They won’t even allow us liberty of thought, and that is all I want.”

Judith Sargent Murray wrote the most systematic expression of a feminist position in this period in 1779, although was not published until 1790. Her essay, On the Equality of the Sexes, challenged the view that men had greater intellectual capacities than women. Instead, she argued that whatever differences existed between the intelligence of men and women were the result of prejudice and discrimination that prevented women from sharing the full range of male privilege and experience. Murray championed the view that the order of nature demanded full equality between the sexes, but that male domination corrupted this principle.

Like many other of the most radical voices of the Revolutionary Era, Murray’s support for gender equality was largely met by shock and disapproval. Revolutionary and early America remained a place of male privilege. Nevertheless, the understanding of the proper relationships among men, women, and the public world underwent significant change in this period. The republican thrust of revolutionary politics required intelligent and self-disciplined citizens to form the core of the new republic. This helped shape a new ideal for wives as republican mothers who could instruct their children, sons especially, to be intelligent and reasonable individuals. This heightened significance to a traditional aspect of wives’ duties brought with it a new commitment to female education and helped make husbands and wives more equal within the family.

Although Republican Motherhood represented a move toward greater equality between husbands and wives, it was far less sweeping than the commitment to equality put forth by women like Judith Sargent Murray. In fact, the benefits that accompanied this new ideal of motherhood were largely restricted to elite families that had the resources to educate their daughters and to allow wives to not be employed outside the household. Republican motherhood did not meaningfully extend to White working women and was not expected to have any place for enslaved women.

NATIVE AMERICANS

While the previous explorations of African American and white female experience suggest both the gains and limitations produced in the Revolutionary Era, from the perspective of almost all Native Americans the American Revolution was an unmitigated disaster. At the start of the war, Patriots worked hard to try to ensure native neutrality, for they could provide strategic military assistance that might decide the struggle. Gradually, however, it became clear to most native groups that an independent America posed a far greater threat to their interests and way of life than a continued British presence that restrained American westward expansion.

Cherokees and Creeks, among others tribes in the southern interior and most Iroquois nations in the northern interior provided crucial support to the British war effort. With remarkably few exceptions, Native American support for the British was close to universal.

The experience of the Iroquois Confederacy In current-day northern New York provides a clear example of the consequences of the Revolution for Native American. The Iroquois represented an alliance of six different native groups who had responded to the dramatic changes of the Colonial Era more successfully than most other Natives in the eastern third of North America. Their political alliance, which had begun to take shape in the 1400, even before the arrival of European colonists, was the most durable factor in their persistence in spite of the disastrous changes brought on by European contact. During the American Revolution, the Confederacy fell apart for the first time since its creation as different Iroquois groups fought against one another.

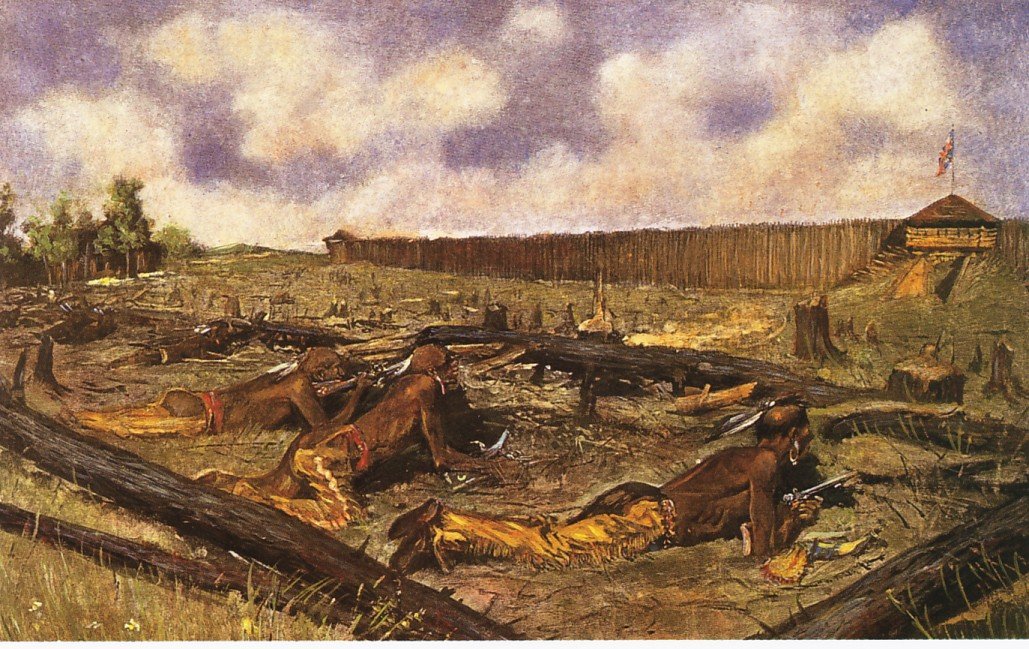

The Mohawk chief Thayendanegea, known to English-speaking Americans as Joseph Brant, was the most important Iroquois leader in the Revolutionary Era. He convinced four of the six Iroquois nations to join him in an alliance with the British and was instrumental in leading combined Native, British, and Loyalist forces on punishing raids in western New York and Pennsylvania in 1778 and 1779. These were countered by a devastating Patriot campaign into Iroquois country that was explicitly directed by General Washington to both engage warriors in battle and to destroy all Indian towns and crops so as to limit the military threat posed by the Native-British alliance. Secondary Source: Painting

Secondary Source: Painting

The Siege of the Fort at Detroit by Frederic Remington.

In spite of significant Native American aid to the British, the European treaty negotiations that concluded the war in 1783 had no native representatives. The Iroquois and other tribes had not surrendered nor suffered a final military defeat, however, the United States claimed that its victory over the British meant a victory over Natives as well. Not surprisingly, due to their lack of representation during treaty negotiations, Native Americans received very poor treatment in the diplomatic arrangements. The British retained their North American holdings north and west of the Great Lakes, but granted the new American republic all land between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. In fact, this region was largely unsettled by Whites and mostly inhabited by Native Americans. As a member of the Wea tribe complained about the failed military alliance with the British, “In endeavoring to assist you it seems we have wrought our own ruin.” Even groups like the Oneida, one of the Iroquois nations that allied with the Americans, were forced to give up traditional lands.

Despite the sweeping setback to Native Americans represented by the American Revolution, native groups in the trans-Appalachian west would remain a vital force and a significant military threat to the new United States. Relying on support from Spanish colonists in New Orleans as well as assistance from the British at Fort Detroit, various Native groups continued to resist Anglo-American incursions well into the 1800s.

Although the outcome of the Revolution for most Native American groups was disastrous, their continued struggle for autonomy, independence, and full legal treatment resulted in partial victories at a much later date. In some ways, this native struggle showed a more thorough commitment to certain revolutionary principles than that demonstrated by the Patriots themselves.

YEOMEN AND ARTISANS

The Revolution succeeded for many reasons, but central to them was broad popular support for a social movement that opposed monarchy and the hereditary privilege. Diverse Americans rallied to the cause to create an independent American republic in which individuals would create a more equal government through talent and a strong commitment to the public good. Two groups of Americans most fully represented the independent ideal in this republican vision for the new nation: yeomen farmers and urban artisans. These two groups made up the overwhelming majority of the White male population, and they were the biggest beneficiaries of the American Revolution.

The yeomen farmer who owned his own modest farm and worked it primarily with family labor remains the embodiment of the ideal American: honest, virtuous, hardworking, self-sufficient, and independent. These same values made yeomen farmers central to the republican vision of the new nation. Because family farmers did not exploit large numbers of other laborers and because they owned their own property, they were seen as the best kinds of citizens to have political influence in a republic.

While yeomen represented the largest number of White farmers in the Revolutionary Era, artisans were a leading urban group making up at least half the total population of seacoast cities. artisans were skilled workers drawn from all levels of society from poor shoemakers and tailors to elite metal workers. The silversmith Paul Revere is the best-known artisan of the Revolution, and exemplifies an important quality of artisans. They had contact with a broad range of urban society. These connections helped place artisans at the center of the Revolutionary movement and it is not surprising that the origins of the Revolution can largely be located in urban centers like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, where artisans were numerous. Like yeomen farmers, artisans also saw themselves as central figures in a republican order where their physical skill and knowledge of a specialized craft provided them with the personal independence and hard-working virtue to be good citizens.

The representatives elected to the new republican state governments during the Revolution reflected the dramatic rise in importance of independent yeomen and artisans. A comparison of the legislatures in six colonies (New York, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, and South Carolina) before the war reveals that 85% of the assemblymen were very wealthy, but by war’s end in 1784, yeomen and artisans of moderate wealth made up 62% of elected officials in the three northern states, while they formed 30%, a significant minority, in the southern states. The Revolution’s greatest achievement, and it was a major change, was the expansion of formal politics to include independent workingmen of modest wealth.

THE AGE OF REVOLUTION

The American Revolution needs to be understood in a broader framework than simply that of domestic events and national politics. The American Revolution started a trans-Atlantic Age of Revolution. Thomas Paine, the author of Common Sense, permits a biographical glimpse of the larger currents of revolutionary change in this period. Paine was English-born and had been in the American colonies less than two years when he wrote what would become the most popular publication of the American Revolution.

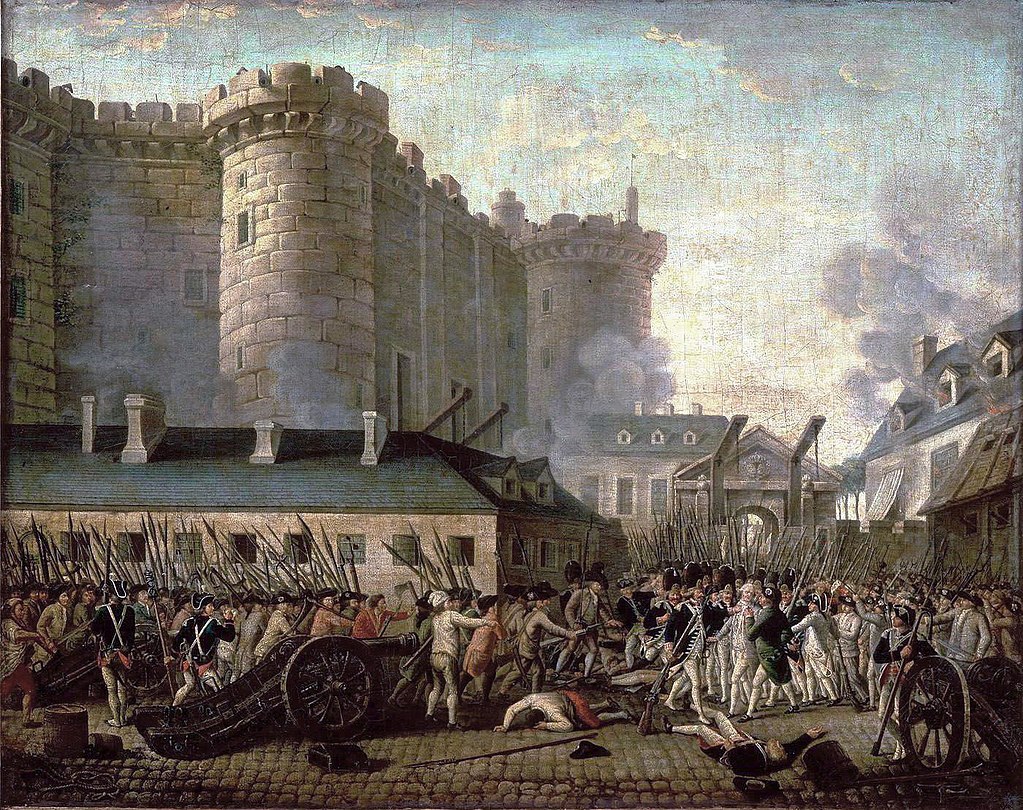

Paine foresaw that the struggle to create an independent republic free of monarchy was a cause of worldwide importance. For Paine, success would make America “an asylum for all mankind.” After the war, Paine returned to England and France where he continued his radical activism by publishing a defense of the French Revolution, in 1791 in his most famous work, The Rights of Man. Paine also served as a politician in revolutionary France. His international role reveals some of the connections among different countries at the time. Secondary Source: Painting

Secondary Source: Painting

The Storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789 is one of the iconic events of the French Revolution. The people of Paris raided the infamous prison and released political prisoners. Bastille Day is a national holiday in France, roughly equivalent to the Fourth of July in the United States.

The French Revolution surely sprung from important internal dynamics, but the connection between the French struggle that began in 1789 and the American Revolution was widely acknowledged at the time. As a symbol of the close relationship, the new French government sent President Washington the key to the door of the Bastille, the prison that had been destroyed by a Parisian revolutionary crowd in one of the great collective actions of the French Revolution. For a time, most Americans celebrated the French overthrow of an absolutist monarch in favor of a constitutional government.

However, in 1792 and 1793 the French Revolution took a dark turn with the beheading of the king. Thus began a period of radicalization that saw significant action on behalf of oppressed groups, including the poor, women and racial outcasts. Unfortunately, this period was also marked by rapidly rising violence that was often sanctioned by the revolutionary government. The violence swept beyond the boundaries of the French revolutionary republic, as it became locked in a war against a coalition of traditional European powers headed by Great Britain.

The winds of the Age of Revolution soon carried back across the Atlantic to the French colony of St. Domingue in the Caribbean. Here, enslaved people responded to the Paris government’s abolition of racial distinctions with a rebellion that began in 1791. Long years of violent conflict followed that ended with the creation of the independent black-run Republic of Haiti in 1804 and the United States was joined by a second republican experiment in the New World.

In comparison to the French and Haitian Revolutions, the lack of radical change in the American Revolution is glaring. The benefits of the American Revolution for the poor, for women, and, perhaps most of all, for enslaved people, were very limited. Nevertheless, the American Revolution did transform American society in meaningful ways and it accomplished its changes with comparatively little internal violence.

Most notably of all, the American Revolution created new republican political institutions that proved to be remarkably stable and long lasting. For all its limitations, the American Revolution had built a framework that allowed for future inclusion and redress of wrongs.

CONCLUSION

For most Americans, life was not significantly different after the Revolution. For some, they were decidedly worse off. For a Revolution purportedly intended to bring rights inspired by the Enlightenment to the masses, few people actually enjoyed any more rights after all was said and done than they had under British rule.

What do you think? Was the American Revolution actually revolutionary?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The American Revolution led to different outcomes for different groups of people. It was good for landowners and artisans, but not good for loyalists, slaves and Native Americans.

The Declaration of Independence is one of the most important documents in American history. The introduction laid out basic ideas about human freedom and the meaning of America. Over time we have expanded our idea of what the Declaration means and who it applies to. For example, in the beginning the phrase “all men are created equal” only applied to White men who owned property. Today, we include men and women of all races and all stations in life.

Soldiers who fought in the War for Independence had a difficult time. In the beginning of the war, the American army was made up of various volunteer militias. As the war progressed, Washington fashioned a professional army, but they were poorly paid and poorly equipped by Congress and mutinies and desertion were common. At the end of the war, the army was a powerful force and the people and the government were suspicious that military officers might try to take power for themselves.

Loyalists were treated poorly throughout the war and especially afterward. Many fled to Britain or Canada.

The Revolution was not an advancement in freedom for African Americans. The British offered freedom for slaves who agreed to fight for the British army, so the Americans were effectively fighting to perpetuate slavery. There was a rise in the population of free African Americans in the North during the war and institutions such as churches developed. The ideas of liberty expressed in the Declaration were embraced by African Americans in later generations who used it as a rallying cry for emancipation and civil rights.

Although women contributed a great deal to the success of the war effort, they were not included in the new governments that followed. Women did become the primary teachers of revolutionary ideas to their children, thus gaining the position of preservers and perpetuators of the essential nature of the American experiment.

Native Americans lost badly. Tribes had almost universally supported the British who had promised to help secure their land rights against encroaching American settlers. The British loss contributed to efforts by Native American leaders to form intertribal alliances between the Great Lakes and Mississippi River area against the new American nation.

Because the Founding Fathers gave voting rights to White men who owned land, small farmers came out of the Revolution as victors. Artisans such as silversmith Paul Revere also came out of the Revolution well. Of course, most of the Founding Fathers were wealthy landowners and they also benefited from the Revolution.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

African Methodist Episcopal Church: The first major protestant religious organization established primarily by and for African Americans in the United States.

Yeoman Farmer: An American who owned his own modest farm a primarily with family labor. According to Thomas Jefferson, he was the embodiment of the ideal American: honest, virtuous, hardworking, and independent.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Republican Motherhood: An idea that developed after the American Revolution centered on the belief that it was the role of women to uphold the ideals of the Revolution by passing on republican values to the next generation. The term was coined by historians in the 20th Century.

Study on Quizlet (Readings 1 & 2 Combined)

Did Loyalists do anything to stop the tar and feathering harassment? Did they ever try to get revenge?

How similar was the American Revolution to the French Revolution?

What happened to the closeted Loyalists? Even after the colonists agreed not to pursue and harass them, did they still reveal themselves?

Was the Constitution ever supported by yeoman farmers?

What if women had the same powers as men? Would our society be structured more differently today?

Did some of the loyalist hide their real feelings to escape the torture of the patriots?

How would Republican Motherhood have made an impact to the effects of abortion rights and transgender rights?

Was there anyone else like Judith Sargent Murray that created a big impact ?

Were the American loyalist that went to London after the war treated differently by British born citizens? Did they see them so Americans or as “one of their own” ?

(Ex. even though many people of color were born in America, they are still looked down on and mistreated due to their race. )

see them as americans*

How has the Declaration’s interpretation been changed over time to match modern ideals?

Did the rise of the free black population influence other states to stop slavery?

Why were groups such as women and slaves not included within the final draft of the Declaration of Independence, while a long list of grievances were included, even though they were a big part of American history?

For the Loyalists that chose to stay in America after the war how did the Americans treat them? And are there any instances of large groups of Loyalists trying to rise up and overthrow the government to revert back to being part of Great Britain?

was there another member of the hutchinson family that faced punishment for having different beliefs? if so, what was their opinion and what did they disagree on?

Thomas Hutchinson was kicked out of America for being a Loyalist during the revolution.

Did any Loyalists stay in America after the Declaration of Independence?

When did people decide that the Declaration of Independence could be for human rights too?

At the time when women were considered inferior, did women also believe this? Did they believe that they were less competent or did they just suppress their dissatisfaction towards gender roles?

I believe some women believe that they were less competent for they did not get the same amount of education as men did. However, some other women may have had their thoughts of diissatifaction, some may have tried to voice their opinions.

Republican Motherhood was an ideal largely restricted to elite families. It wasn’t intended to extend to white working women and not enslaved women, but did the tyrannized women ever tried to speak up for their rights as well?

When Abigal Adams suggested to her husband John Adams that in the “new Code of Laws” that he helped draft at the Continental Congress, he should, “Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them.” It didn’t work out that way. What was preventing them from making it happen?

I think that this didn’t happen because women were seen inferior to men. In their eyes , men were the ones who were going to make the most change and women were better off just in the house

It’s sad that the Native Americans aid the British and in the end they lack representation during treaty negotiations.

I agree with your statement. It has been shown numerous times throughout history that Native Americans have repeatedly been neglected and ignored. It makes me wonder what would the future of different countries emerge as if Natives and foreigners had just gotten along during those fateful encounters?

When children of current slaves were freed, Why did the age of the child particularly need to be 25? Did it have to do with anything of being old enough for the child to live on his/her own? Or was it just a chosen age?

Why did slavery still continue despite the effort that had been done in the Revolution? Many battles were fought with Enslaved Americans helping the armies and people had been fighting for the abolishment of slavery. What was it that made it continue still until 1865?

I think the fact itself is that everybody was entitled to their own beliefs and opinions. Although slavery is an awful act, back then it was seen as “normal” for African Americans to be treated as property and not a human being. Despite numerous attempts and battles pushing for the abolishment of slavery, an act that was deemed as customary would have taken a duration to put an end to these efforts.

It is mentioned that Thomas Paine the author of Common Sense, also served as a politician in France, how did Paine support the French revolution and as a politican what were some of his most prominent actions and how did these actions affect the French Revolution?

Why did the French take a dark turn in their revolution? What made the Haiti Revolution so successful?

Why do we celebrate July 4th for our Founding Fathers when the Founders used the American Revolution to gain power for their own personal gain? Because in the Introduction, and Conclusion it said that After the American Revolution for Americans life either stayed the same or got worse.

Despite having a growing increase in emancipated slaves, Racism still persisted throughout the colonies. How exactly did the whites treat the new free black population? Were they accepted for a little bit or were they subject to prejudice/hate crimes from the very beginning of Independent America?

During this time, many enslaved people were liberated in states that were later part of the confederacy/ border states. Was there a problem where emancipated slaves were taken back as slaves during this time?

Why were middle and upper-class white women the ones who were given an education? How about the lower class and the enslaved women? Don’t you think that ruins the whole concept of Republican Motherhood?

Back then it was only natural for someone with a respected class to receive an education. People thought the middle and upper classes needed to be educated because they can help in raising important patriots. People thought important influential patriots wouldn’t come from the lower class and enslaved families so women didn’t need to be educated.