TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

In his 1997 book, “Guns, Germs and Steel”, historian Jared Diamond summarized his theory as to why Europeans were able to conquer so much of the world in the centuries between 1492 and 1900. His thesis became the three words of the title of his book, and his reasoning is sound.

Europeans had metalworking technology. It is true gunpowder was an invention of China, but Europeans arrived on the battlefields of the Age of Discovery with weapons far superior to anything the defenders could muster.

Importantly also, Europeans and Africans carried diseases to the New World that devastated Native American populations. As part of the exchange of ideas, foods, animals and microbes between the Old World and New, diseases that Native Americans had no immunity for swept across the hemisphere and wiped out 90% of the population.

But despite these advantages, both understood and mysterious at the time, it defies logic that a few thousand Europeans could overthrow the powerful empires of Central and South America, and subdue millions of people in just a few decades. How was this possible? Couldn’t the Native Americans see the danger the Europeans posed?

Why didn’t millions of Native Americans stop a few thousand European conquerors?

LOS CONQUISTADORS

Columbus’s discovery opened a floodgate of Spanish exploration. Inspired by tales of rivers of gold and timid, malleable natives, later Spanish explorers were relentless in their quest for land and gold. Known as conquistadors – conquerors – they came by the thousands and established a thriving, albeit violent and culturally destructive empire in America.

THE FALL OF THE AZTEC

Hernan Cortés hoped to gain hereditary privilege for his family, tribute payments and labor from natives, and an annual pension for his service to the crown. Cortes arrived on Hispaniola in 1504 and took part in the conquest of that island.

Long before Cortés landed in Mexico at Vera Cruz on Good Friday, 1519, portents of doom appeared. A comet “bright as to turn night into day” lit the sky. Dismayed soothsayers and astrologers maintained they did not see it. For this unhelpful approach, Montezuma, the king of the Aztec Empire, cast them into cages where they starved to death. Then, an important temple burned. Lastly, hunters brought Montezuma a bird with a mirror strapped to its head. In it he saw large numbers of people “advance as for war; they appeared to be half men half deer.”

How much of this is fact? How much is myth? By the time spies brought tales of mountains floating upon the sea (Spanish galleons), and men with “flesh very white…a long beard and hair to their ears,” Montezuma’s nerves were shattered. Was this the legendary feathered serpent god, Quetzalcotl, who having vanished into the eastern ocean, now returned?

Montezuma half-convinced himself Cortés was a god. He sent Cortés the feathery costume of Quetzalcotl with other gifts, including “twenty ducks made of gold, very natural looking.” Cortés took the bold move of marching on Tenochtitlan. With a force of 500 Spanish soldiers and whatever warriors he recruited along the way, he faced Montezuma on the city’s southern causeway on November 8, 1519. Montezuma invited him in.

Cortés and his men were astonished by the incredibly sophisticated causeways, gardens, and temples in the city, but they were horrified by the practice of human sacrifice that was part of the Aztec religion. Above all else, the Aztec wealth in gold fascinated the Spanish adventurers. The Conquest of Mexico as depicted by muralist Diego Rivera

The Conquest of Mexico as depicted by muralist Diego Rivera

Hoping to gain power over the city, Cortés took Moctezuma, the Aztec ruler, hostage. The Spanish then murdered hundreds of high-ranking Aztecs during a festival to celebrate Huitzilopochtli, the god of war. This angered the people of Tenochtitlan, who rose up against the interlopers in their city. Cortés and his people fled for their lives, running down one of Tenochtitlan’s causeways to safety on the shore. Smarting from their defeat at the hands of the Aztec, Cortés slowly created alliances with native peoples who resented Aztec rule. It took nearly a year for the Spanish and the tens of thousands of native allies who joined them to defeat the Mexica in Tenochtitlan, which they did by laying siege to the city. Only by playing upon the disunity among the diverse groups in the Aztec Empire were the Spanish able to capture the grand city of Tenochtitlan. In August 1521, having successfully fomented civil war as well as fended off rival Spanish explorers, Cortés claimed Tenochtitlan for Spain and renamed it Mexico City.

The traditional European narrative of exploration presents the victory of the Spanish over the Aztec as an example of the superiority of the Europeans over the savage Indians. However, the reality is far more complex. When Cortés explored central Mexico, he encountered a region simmering with native conflict. Far from being unified and content under Aztec rule, many peoples in Mexico resented it and were ready to rebel. One group in particular, the Tlaxcalan, threw their lot in with the Spanish, providing as many as 200,000 fighters in the siege of Tenochtitlan. The Spanish also brought smallpox into the valley of Mexico. The disease took a heavy toll on the people in Tenochtitlan, playing a much greater role in the city’s demise than did Spanish force of arms.

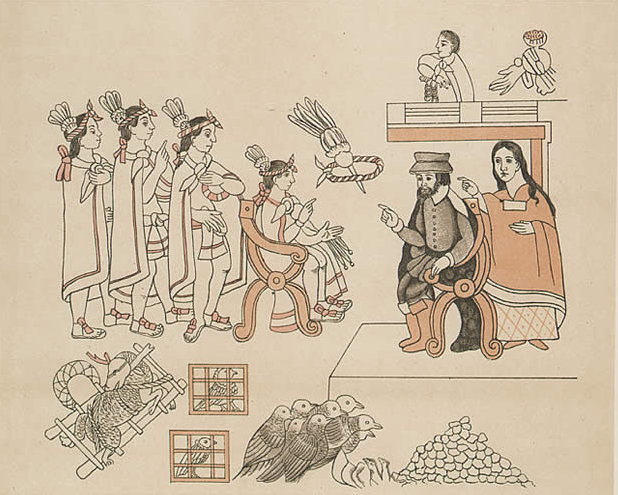

An Aztec codex depicting Cortes and Aztec leaders which la Malinche interpreting.

Cortés was also aided by a Nahua woman called Malintzin (also known as La Malinche or Dona Marina, her Spanish name), whom the natives of Tabasco gave him as tribute. Malintzin translated for Cortés in his dealings with Moctezuma and, whether willingly or under pressure, entered into a physical relationship with him. Their son, Martin, may have been the first mestizo (person of mixed indigenous American and European descent). Malintzin remains a controversial figure in the history of the Atlantic World; some people view her as a traitor because she helped Cortés conquer the Aztecs, while others see her as a victim of European expansion. In either case, she demonstrates one way in which native peoples responded to the arrival of the Spanish. Without her, Cortés would not have been able to communicate, and without the language bridge, he surely would have been less successful in destabilizing the Aztec Empire. By this and other means, native people helped shape the conquest of the Americas.

THE FALL OF THE INCA

The Spanish explorer Francisco Pizarro, first arrived in South America in 1526 and recognized the wealth and abundance that could be won by conquering the Inca Empire which was then at its greatest power. He went back to Spain to ask for the official blessing of the Spanish crown to conquer the area and become governor. Upon his return two years later with the royal blessing, Pizarro and a small force of Spanish conquistadors set out to recreate Cortés’s success against the Aztec. Many problems within the Inca Empire worked to their advantage. Foremost among these was that the Inca had turned against themselves in a civil war.

The ruling Inca emperor, Huayna Capac, and his designated heir, Ninan Cuyochic, died of disease. It was most likely smallpox, which had quickly traveled down to South America after the arrival of Spanish explorers in Central America. Brothers Huascar and Atahualpa, two sons of the emperor Huayna Capac, both wanted to rule after their father’s death. Initially, Huascar captured the throne in Cusco, claiming legitimacy. However, Atahualpa had a keen military mind and close relations with the military generals at the time, and proved to be the deadlier force. By 1532, Atahualpa had overpowered his brother’s forces via intrigue and merciless violence, scaring many local populations away from standing up to his power. This civil war left the population in a precarious position just as Pizarro and his small force were arriving.

The Spanish forces went to meet with Atahualpa and demanded he convert to Catholicism and recognize the authority of Charles I of Spain. Because of the language barrier, the Inca rulers probably did not understand much of these demands, and the meeting turned violent, leaving thousands of native people dead. The Spanish captured Atahualpa and kept him hostage, demanding ransoms of silver and gold. They insisted that Atahualpa agree to be baptized. Although the Inca ruler was mostly cooperative in captivity, and was finally baptized, the Spanish killed him on August 29, 1533, essentially ending the potential for larger Inca attacks on Spanish forces.

Even though the Inca Civil War made it easier for the Spanish armies to gain control initially, many other contributing factors brought about the demise of Inca rule and the crumbling of local populations. As scholar Jared Diamond points out, the Inca Empire was already facing threats. Local unrest in the provinces after years of paying tribute to the Inca elite created immediate allies for the Spanish against the Inca rulers. Second, demanding terrain throughout the empire made it difficult to keep a handle on populations and goods as the empire expanded. Third, diseases that the population had never been exposed to, such as smallpox, diphtheria, typhus, measles, and influenza, devastated large swaths of the population. And finally, superior Spanish military gear, including armor, horses, and weapons, overpowered the siege warfare more common in the Inca Empire.

The Spanish named their vast newly won region the Viceroyalty of Peru and set up a Spanish system of rule, which effectively suppressed any type of uprising from local communities. The Spanish system destroyed many of the Inca traditions and ways of life in a matter of years. Their finely honed agricultural system, which utilized tiered fields in the mountains, was completely disbanded. The Spanish also enforced heavy manual labor taxes, called mita, on the local populations. This meant every family had to offer up one person to work in the highly dangerous gold and silver mines. If that family member died, which was common, the family had to replace the fallen laborer. The Spanish also enforced heavy taxes on agriculture, metals, and other fine goods. The population continued to suffer heavy losses due to disease as Spanish rule settled into place.

THE SPANISH IN NORTH AMERICA

Spain’s drive to enlarge its empire led other hopeful conquistadors to push further into the Americas, hoping to replicate the success of Cortes and Pizarro. Hernando de Soto had participated in Pizarro’s conquest of the Inca, and from 1539 to 1542 he led expeditions to what is today the southeastern United States, looking for gold. He and his followers explored what is now Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Texas. Everywhere they traveled, they brought European diseases, which claimed thousands of native lives as well as the lives of the explorers. In 1542, de Soto himself died during the expedition. The surviving Spaniards, numbering a little over 300, returned to Mexico City without finding the much-anticipated mountains of gold and silver.

Francisco Vasquez de Coronado was born into a noble family and went to Mexico, by then called New Spain, in 1535. He presided as governor over the province of Nueva Galicia, where he heard rumors of wealth to the north. Between 1540 and 1542, Coronado led a large expedition of Spaniards and native allies to the lands north of Mexico City, and for the next several years, they explored the area that is now the southwestern United States. Rather than leading to the discovery of gold and silver, however, the expedition simply left Coronado bankrupt.

THOSE WHO LOST THE CONQUEST

Physical power to work the fields, build villages, process raw materials is necessary for maintaining a society. In the 1500s and 1600s, humans could derive power only from the wind, water, animals, or other humans. Everywhere in the Americas, a crushing demand for labor bedeviled Europeans because there were not enough colonists to perform the work necessary to keep the colonies going. Spain granted encomiendas, legal rights to native labor, to conquistadors who could prove their service to the crown. This system reflected the Spanish view of colonization: the king rewarded successful conquistadors who expanded the empire. Some native peoples who had sided with the conquistadors, like the Tlaxcalan, also gained encomiendas. Malintzin, the Nahua woman who helped Cortés defeat the Aztec, was granted one.

The Spanish believed native peoples would work for them by right of conquest, and, in return, the Spanish would bring them Catholicism. In theory the relationship consisted of reciprocal obligations, but in practice the Spaniards ruthlessly exploited it, seeing native people as little more than beasts of burden. Convinced of their right to the land and its peoples, they sought both to control native labor and to impose what they viewed as correct religious beliefs upon the land’s inhabitants. Native peoples everywhere resisted both the labor obligations and the effort to change their ancient belief systems. Indeed, many retained their religion or incorporated only the parts of Catholicism that made sense to them.

The system of encomiendas was accompanied by a great deal of violence. One Spaniard, Bartolomé de Las Casas, denounced the brutality of Spanish rule. A Dominican friar, Las Casas had been one of the earliest Spanish settlers in the Spanish West Indies. In his early life in the Americas, he owned Native American slaves and was the recipient of an encomienda. However, after witnessing the savagery with which encomenderos (recipients of encomiendas) treated the native people, he reversed his views. In 1515, Las Casas released his native slaves, gave up his encomienda, and began to advocate for humane treatment of native peoples. He lobbied for new legislation, eventually known as the New Laws, which would eliminate slavery and the encomienda system.

Las Casas’s writing about the Spaniards’ horrific treatment of Native Americans helped inspire the so-called Black Legend, the idea that the Spanish were bloodthirsty conquerors with no regard for human life. Perhaps not surprisingly, those who held this view of the Spanish were Spain’s imperial rivals. English writers and others seized on the idea of Spain’s ruthlessness to support their own colonization projects. By demonizing the Spanish, they justified their own efforts as more humane. Almost all European colonizers, however, shared a disregard for Native Americans.

Native Americans were not the only source of cheap labor in the Americas. By the middle of the 1500s, Africans formed an important element of the labor landscape, producing the cash crops of sugar and tobacco for European markets. Europeans viewed Africans as non-Christians, which they used as a justification for enslavement. Denied control over their lives, slaves endured horrendous conditions.

At every opportunity, they resisted enslavement, and their resistance was met with violence. Indeed, physical, mental, and sexual violence formed a key strategy among European slaveholders in their effort to assert mastery and impose their will. The Portuguese led the way in the evolving transport of slaves across the Atlantic. Slave “factories” on the west coast of Africa, like Elmina Castle in Ghana, served as holding pens for slaves brought from Africa’s interior. In time, other European imperial powers would follow in the footsteps of the Portuguese by constructing similar outposts on the coast of West Africa.

The Portuguese traded or sold slaves to Spanish, Dutch, and English colonists in the Americas, particularly in South America and the Caribbean, where sugar was a primary export. Over 10 million African slaves were eventually forcibly moved to the Americas where they found themselves mining and working on plantations.

Las Casas estimated that by 1550, there were 50,000 slaves on the island of Hispaniola. However, it is a mistake to assume that during the very early years of European exploration all Africans came to America as slaves. Some were free men who took part in expeditions, for example, serving as conquistadors alongside Cortés in his assault on Tenochtitlan. Nonetheless, African slavery was one of the most tragic outcomes in the emerging Atlantic World.

If the story of the Conquest of the Americas by the Spanish seems to be a long saga of failure and suffering on the part of Native Americans and Africans, that is because it is indeed a long saga of suffering. However, there is one story of resistance to Spanish rule that has come to be celebrated in modern times by those who champion indigenous rights, and that is the story of the Pueblo Revolt.

Intent on expanding their empire, Spanish conquistadors looked north to the land of the Pueblo Indians in what is now the state of New Mexico. Under orders from King Philip II, Juan de Oñate violently explored the American southwest for Spain in the late 1590s. The Spanish hoped that what we know as New Mexico would yield gold and silver, but the land produced little of value to them. In 1610, Spanish settlers established themselves at Santa Fe. As they had in other Spanish colonies, Franciscan missionaries labored to bring about a spiritual conquest by converting the Pueblo to Catholicism. At first, the Pueblo adopted the parts of Catholicism that dovetailed with their own long-standing view of the world. However, Spanish priests insisted natives discard their old ways entirely and angered the Pueblo by focusing on the young, drawing them away from their parents. This deep insult, combined with an extended period of drought and increased attacks by local Apache and Navajo in the 1670s, which the Pueblo came to believe were linked to the Spanish presence, moved the Pueblo to push the Spanish and their religion from the area. Pueblo leader Popé demanded a return to native ways so the hardships his people faced would end. To him and to thousands of others, it seemed obvious that “when Jesus came, the Corn Mothers went away.” In 1680, Popé led and uprising against Spanish rule known now as the Pueblo Revolt and tried bring about a return to prosperity and a pure, native way of life.

GALLEONS, TRADE AND PIRATES

As Spain’s New World empire grew, Spanish merchants expanded their economic empire. By 1565, Columbus’s original dream of connecting Europe and Asia by water was essentially complete. Twice each year, giant galleons departed Manila Harbor in the Spanish colony of the Philippines on route to Acapulco on the Pacific Coast of Mexico.

The galleon trade was supplied by merchants largely from Fujian Province in southern China who traveled to Manila to sell the Spaniards spices, porcelain, ivory, lacquerware, processed silk cloth and other valuable commodities. Cargoes varied from one voyage to another but often included goods from all over Asia including jade, wax, gunpowder and silk from China; amber, cotton and rugs from India; spices from Indonesia and Malaysia; and a variety of goods from Japan, including fans, chests, screens and porcelain. These goods were mostly bought by silver mined from Mexico and Potosí in Bolivia. In addition, slaves from various origins were transported from Manila. The cargoes arrived in Acapulco and were transported by land across Mexico to the port of Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico, where they were loaded onto the Spanish treasure fleet bound for Spain.

This vast array of wealth, packed tightly into a few ships which travelled on predictable schedules a few times each year to take advantages of the prevailing winds was a ripe target for Dutch and English pirates and the galleons were outfitted with a potent array of weaponry to protect them. The cat and mouse game between the Spanish ships and the pirates inspired stories and legends that fuel the imagination even today. They were the original, and real pirates of the Caribbean. Sometimes these great ships were lost in storms and treasure hunters continue to scour the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea looking for lost Spanish gold.

A reconstructed Spanish galleon. These large cargo ships carried the wealth of Asia and the Americas across both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans during the height of Spain’s imperial power.

THE SPANISH GOLDEN AGE

The exploits of European explorers had a profound impact both in the Americas and back in Europe. An exchange of ideas, fueled and financed in part by New World commodities, began to connect European nations and, in turn, to touch the parts of the world that Europeans conquered.

In Spain, gold and silver from the Americas helped to fuel a golden age, the Siglo de Oro, when Spanish art and literature flourished. Riches poured in from the colonies, and new ideas poured in from other countries and new lands. The Hapsburg dynasty, which ruled a collection of territories including Austria, the Netherlands, Naples, Sicily, and Spain, encouraged and financed the work of painters, sculptors, musicians, architects, and writers, resulting in a blooming of Spanish Renaissance culture. One of this period’s most famous works is the novel The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha, by Miguel de Cervantes. This two-volume book (1605 and 1618) told a colorful tale of an hidalgo (gentleman) who reads so many tales of chivalry and knighthood that he becomes unable to tell reality from fiction. With his faithful sidekick Sancho Panza, Don Quixote leaves reality behind and sets out to revive chivalry by doing battle with what he perceives as the enemies of Spain.

Las Meninas (The Maids of Honor), painted by Diego Velazquez in 1656, is unique for its time because it places the viewer in the place of King Philip IV and his wife, Queen Mariana.

Spain attracted innovative foreign painters such as El Greco, a Greek who had studied with Italian Renaissance masters like Titian and Michelangelo before moving to Toledo. Native Spaniards created equally enduring works. Las Meninas (The Maids of Honor), painted by Diego Velazquez in 1656, is one of the best-known paintings in history. Velazquez painted himself into this imposingly large royal portrait (he’s shown holding his brush and easel on the left) and boldly placed the viewer where the king and queen would stand in the scene.

NEW FRANCE

Competing with Spain, Portugal, the United Provinces (the Dutch Republic), and later Britain, France began to establish colonies in North America, the Caribbean, and India in the 1600s. The French first came to the New World as explorers, seeking a route to the Pacific Ocean and wealth. Major French exploration of North America began under the rule of Francis I of France. In 1524, Francis sent Italian-born Giovanni da Verrazzano to explore the region between Florida and Newfoundland for a route to the Pacific Ocean. Verrazzano gave the names Francesca and Nova Gallia to the land between New Spain and English Newfoundland, thus promoting French interests.

In 1534, Francis sent Jacques Cartier on the first of three voyages to explore the coast of Newfoundland and the St. Lawrence River. Cartier founded New France by planting a cross on the shore of the Gaspé Peninsula. He is believed to have accompanied Verrazzano to Nova Scotia and Brazil, and was the first European to travel inland in North America, describing the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, which he named “The Country of Canadas” after Iroquois names, and claiming what is now Canada for France. He attempted to create the first permanent European settlement in North America at Quebec in 1541 with 400 settlers, but the settlement was abandoned the next year. A number of other failed attempts to establish French settlement in North America followed throughout the rest of the 16th century.

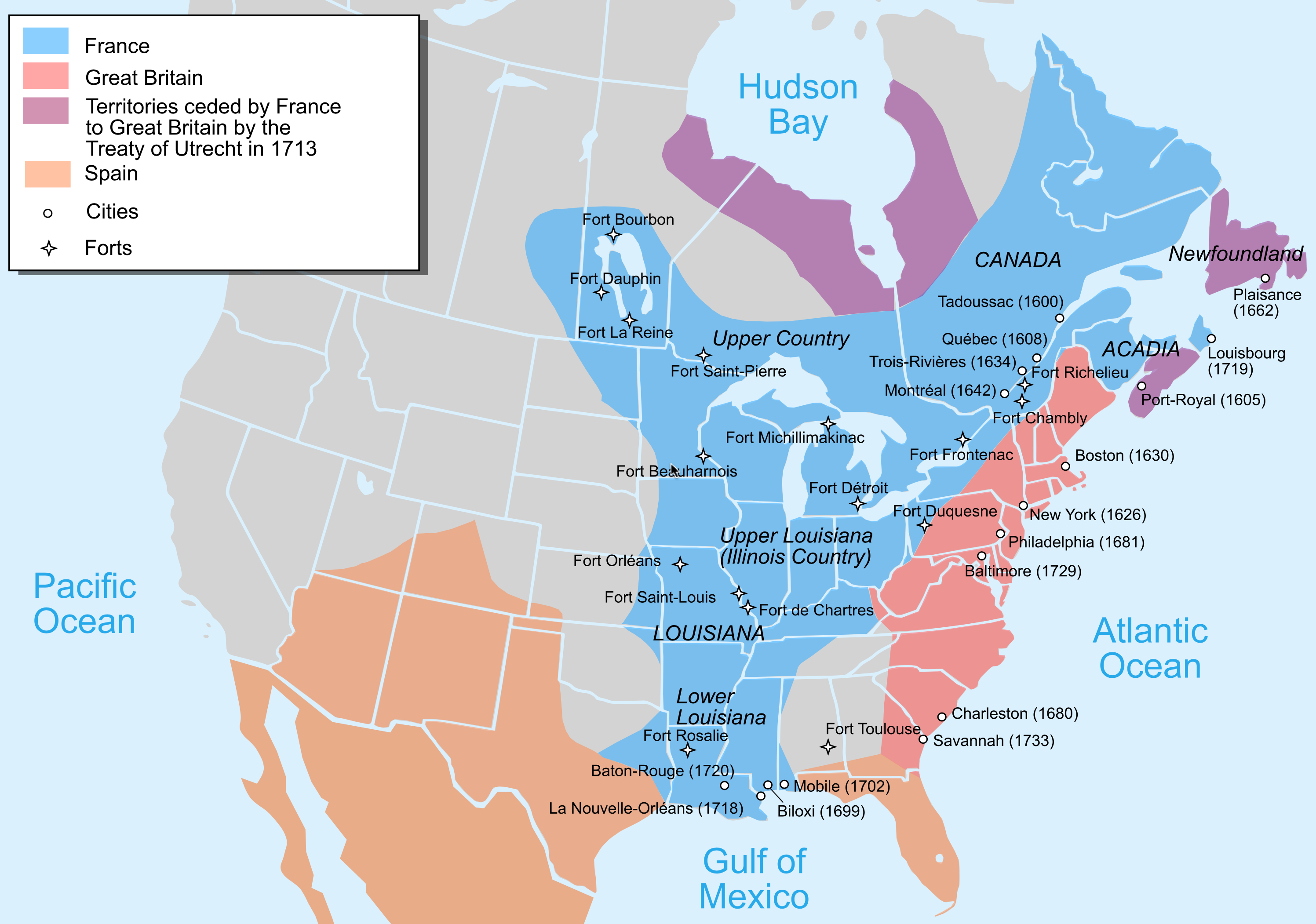

New France stretched from the mouth of the Mississippi River at the Gulf of Mexico north, through the Great Lakes Region and then on along the St. Lawrence River to the Atlantic Coast of what is now Canada. Despite its impressive size on the map, New France was sparsely populated relative to the Spanish and later English colonies.

Although through alliances with various Native American tribes, the French were able to exert a loose control over much of the North American continent, areas of French settlement were generally limited to the St. Lawrence River Valley. Based more on cooperation than conquest, the French colonies profited from a growing trade in beaver fur. French coureur des bois (runners of the woods) travelled the interior of New France trading European products for beaver pelts. The pelts were shipped back to Europe where they were manufactured into hats.

Because the fur trade relied on good relationships with Native Americans, there was relatively little interest in colonialism in France, which concentrated on dominance within Europe, and for most of its history, New France was far behind the British North American colonies in both population and economic development.

In 1699, French territorial claims in North America expanded still further, with the foundation of Louisiana in the basin of the Mississippi River. The extensive trading network throughout the region connected to Canada through the Great Lakes, was maintained through a vast system of fortifications, many of them centered in the Illinois Country and in present-day Arkansas.

New France was the area colonized by France in North America during a period beginning with the exploration of the Saint Lawrence River by Jacques Cartier in 1534, and ending with the cession of New France to Spain and Great Britain in 1763. At its peak in 1712, the territory of New France extended from Newfoundland to the Rocky Mountains and from Hudson Bay to the Gulf of Mexico, including all the Great Lakes of North America.

In general, what distinguished New France from the other European settlements in the New World was that the French largely got along with the Native Americans, and built very few cities. As trappers, most French colonists travelled, and the fur trade could only be profitable if Native Americans were willing participants. In the end, because they collaborated rather than replaced the Native Americans in their claimed territory, there were actually few French people at all in New France, compared to the density of Spanish and eventually English settlers in their American colonies. This would eventually prove to be a challenge for the French when it came to defending their empire.

AJ Miller’s depiction of a meeting between a French fur trader and Native Americans. French traders often married Native American women.

THE WEST INDIES

As the French empire in North America grew, the French also began to build a smaller but more profitable empire in the West Indies. Settlement along the South American coast in what is today French Guiana began in 1624, and a colony was founded on Saint Kitts in 1625. Colonies in Guadeloupe and Martinique were founded in 1635 and on Saint Lucia in 1650. The food-producing plantations of these colonies were built and sustained through slavery, with the supply of slaves dependent on the African slave trade. Local resistance by the indigenous peoples resulted in the Carib Expulsion of 1660.

France’s most important Caribbean colonial possession was established in 1664, when the colony of Saint-Domingue, known today as Haiti was founded on the western half of the Spanish island of Hispaniola. In the 18th century, Saint-Domingue grew to be the richest sugar colony in the Caribbean. The eastern half of Hispaniola is today’s Dominican Republic, which also came under French rule for a short period after being given to France by Spain in 1795.

In the middle of the 18th century, a series of colonial conflicts began between France and Britain, which ultimately resulted in the destruction of most of the first French colonial empire and the near complete expulsion of France from the Americas.

CONCLUSION

The Spanish and French both built empires in the Americas, but their social and economic systems were vastly different.

The Spanish replaced the Native political leaders with their own royal governors and extracted the mineral wealth of the continent for the glorification of Spain. They brutally converted their new subjects to Christianity and used them as slaves.

The French, on the other hand, did little to populate their new territories and collaborated with the Natives they met in order to trade. True, French missionaries also travelled the wilderness looking for converts, but the French colonial experience lacked the violent streak that marked Spanish America.

Regardless of the differences, in the end, Europeans came to rule in the Americas, to the tremendous detriment of the Native population. Which brings us back to our question.

What do you think? Why didn’t millions of Native Americans stop a few thousand European conquerors?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: Spain developed its American empire through military conquest and because Native Americans died in large numbers from Old World diseases. They focused on extracting precious metals. Alternatively, the French engaged in the beaver trade which led them to develop scattered settlements and cultivate good relationships with Native Americans.

Spanish conquistadors were able to conquer the great empires of Mexico and South America relatively easily in the early 1500s.

Hernán Cortés led an expedition of Spanish troops into the heart of Mexico. They were joined by native groups who had been conquered by the Aztec. Cortés was helped by La Malinche, a native woman who helped him by translating and providing insight into native cultural beliefs. Because of her relationship with Cortés, she is viewed as both the first Mexican, and as a traitor. The Aztecs may have believed Cortés was a god and treated him well. However, when it became clear that the Spanish were obsessed with Aztec gold, fighting ensued. Montezuma, the Aztec emperor was killed and the Spanish replaced the Aztec leadership as the rulers of the kingdom.

Francisco Pizarro repeated Cortés’s success against the Aztec when he led an expedition into South America. Pizarro captured and executed Atahualpa, the Inca emperor and expanded the Spanish Empire into much of South America.

Spanish attempts to find wealth in North America did not go as well. There were not great societies to conquer. Hernando de Soto explored Florida and much of the American South. Coronado explored the American Southwest.

Wherever the Spanish went, they left behind Old World diseases that devastated the local populations. Where they stayed, they implemented the encomienda system. Spanish conquistadors were given land as a reward for their service. They used the local Native American population as slave labor. Some Spanish, such as the priest Bartolomé de Las Casas protested this brutal system, however it ended mostly because Native Americans died from disease and were replaced by African slaves rather than because the Spanish decided to treat their new subjects better.

Great wealth based on gold and silver from America dramatically changed Spain. A golden age of culture in Spain resulted as the royal family patronized artists. Don Quixote of La Mancha was written. The wealth ultimately destroyed Spain because of runaway inflation.

The French also decided to explore America. Their colonies began in what is now Canada where they created the settlements of Quebec and Montreal. They also built the town of New Orleans at the mouth of the Mississippi River, and claimed the vast inland region between Louisiana, the Great Lakes and Canada. The French engaged in fur trapping and did not build large farms or populate large areas. Instead, they worked with the Native population to trade for furs.

The various islands of the Caribbean were divided between various European nations.

VOCABULARY

LOCATIONS

Viceroyalty of Peru: Name for the Spanish colony in South America.

New Spain: The northern Spanish colonies centered in Mexico and Central America.

Elmina Castle: Portuguese slave trading fortress on the Atlantic Coast of Africa in what is now Ghana.

Philippines: Spanish colony in Asia.

New France: The French colony in North America.

Quebec: French colonial settlement in what is now Canada.

Louisiana: French settlement established at the mouth of the Mississippi River.

Haiti: French colony on the island of Hispaniola. It was the most wealthy French possession in the New World because of the slave-based sugar industry there.

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Hernan Cortés: Spanish conquistador who defeated the Aztec.

Montezuma: Last Aztec emperor who was defeated by Cortés.

Quetzalcotl: Mesoamerican feathered serpent god.

La Malinche: Native American woman who helped Cortés defeated the Aztec by providing advice and translation.

Francisco Pizzaro: Spanish conquistador who defeated the Inca empire.

Atahualpa: Inca emperor who was defeated by Pizarro and the Spanish.

Hernando de Soto: Spanish conquistador who explored Florida and the southeastern United States. He failed to find gold or great civilizations to conquer.

Francisco Vasquez de Coronado: Spanish conquistador who explored the southwestern United States.

Bartolomé de Las Casas: Spanish priest who wrote about the mistreatment of Native Americans.

Juan de Oñate: Spanish conquistador who violently explored the American Southwest.

Popé: Pueblo leader who led the Pueblo Revolt and successfully expelled the Spanish from Pueblo territory in 1680.

Miguel de Cervantes: Spanish author during the Siglo de Oro. He wrote Don Quixote and is sometimes referred to as the Spanish equivalent of Shakespeare.

Diego Velazquez: Spanish painter during the Siglo de Oro. He is sometimes considered the greatest classical painter ever.

Jacques Cartier: French explorer who helped found New France.

Coureur des Bois: Literally “Runners of the Woods.” French trappers and traders who travelled the interior of North America trading for beaver fur and living with Native Americans.

![]()

EVENTS

Pueblo Revolt: Uprising led by Popé against the Spanish in 1680.

Siglo de Oro: The golden age of Spain during the 1500s, known as a time when the nation was rich with gold and silver from America, more powerful than its European rivals, and a center for literature and art.

![]()

TECHNOLOGY

Galleons: Giant Spanish and Portuguese ships that carried the wealth of their empires across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

![]()

KEY CONCEPTS

Encomiendas: Spanish system in which conquistadors were rewarded with land and the right to enslave Native Americans.

Black Legend: A retelling of the Spanish colonial era that emphasized the mistreatment of Native Americans in order to portray the Spanish as evil.

Beaver Trade: The foundation of the French colonial economy. Rather than exporting precious minerals or farming, the French relied on trade with Native Americans for this export.

If the French decided to have a populated city and build large farms instead, would they have changed their mind about working with the Native people to trade for furs & fur trapping?

Though most of the profits for the French came from the beaver trade with the Native Americans, that collaboration led to fewer French people and ultimately, difficulty in defending the French empire. Would it have been better for the French if they had colonized the Native American’s claimed territory?

Who did Hernan Cortes allied with when they sieged Aztec empire and why did they hate the Aztecs?

I find it interesting that some Native Americans volunteer helped explorers colonize their land. Maybe they thought it was a good thing and that the explores could help them in some ways.

When Huayna Capac died and one of his sons, Huascar, claimed legitimacy to the throne, did the people want to follow him, or did they want Atahualpa as ruler instead?

https://www.college.columbia.edu/core/content/bartolomé-de-las-casas

This article is about Bartolome de Las Casas. It shows a more detailed story about Las Casas’ journey, advocating for the Indians and indigenous slave labor.

Why were the French able to get along with the Native Americans while other people struggled?

The Spanish were hypocrites for converting Native tribes/peoples into Catholics when they never acted as Christians would. For example, they exploited the Africans and Native Americans as slave labor and oppressed them.

If the natives had the ability to combat these diseases that were pivotal to them losing, could the outcomes of the invasions changed?

How was the bond like between the French and the Native Americans? Since the connections of getting along made New France stand out.

Where did all of those rumors about wealth start?

Why were Europeans less prone to the diseases than Native Americans?

A pattern that I tend to keep seeing is how each of these civilizations have fallen because of European colonizers, even the Philippines. As the Spanish had greater power due to military control and how they can easily conquer civilizations. As they strip communities of their dignity and pride in their culture. As western culture expands and continues to take advantage of them.

How did the Europeans really justify misdeeds and sins as “God’s Will”? They are all like, “Do no bad or else you will go to hell for your sins”, but then start ranting about God’s Will when they start killing off humans.

We know that diseases the Spanish brought to the Americas was a key role in allowing them to conquer the natives, but did the Spanish know that at the time as well? Did they realize what those diseases were doing to the populations and used that to their advantage to take over empires, or was it more of a coincidence and they figured it out later?

If the Europeans didn’t bring all these diseases, would the Native Americans have most definitely fought back?

Why didn’t the French and Native Americans join together/ “join forces” to try and stop/ defeat the spanish from continuing to take over since they collaborated together?

I wonder if the French really could have developed New France more efficiently if they based their beliefs more on conquest instead of cooperation. It was proven by the British and Spanish that conquering land helped their empire grow quickly, but it was not always fair to the Native Americans. The French basically did take over their lands, but when doing so, did the French try to make it beneficial for everyone instead of just their own interests? I think that the fur trade did play a big part in how they cooperated with the Natives, but it also caused them problems.

Why are the Europeans so greedy? Have the European conquerors given thought to how the Native Americans will feel when their whole society needs to change and they will be used as slaves?

Why didn’t the Spanish try to make good relationships with the Inca empire? There would be trade and a good economy on both sides.

Did The French Do Anything To Stop The Spanish From Mistreating The Native Americans? And Why Did The Spanish Treat The Natives So Poorly?

European conquerors were more civilized. They had weapons and resources that the Native Americans didnt have. The Europeans also brought diseases which wiped out most of the native american population. During the war they lacked people, weapons, and resources which brought them down. SInce they became more and more outnumbered the population declined more and more

Why wasn’t Singlo de Oro a thing before it was? What made the art created in this time period so special? What was the difference in art during this period and before it? I also wonder, how did people learn literature when it was not as advanced as it is right now? Literature has kept improving and getting more complex over the centuries. What was the main source of learning literature back then?

Did the Native Americans record how many births or deaths they had each year? Did each tribe have their own rituals for births or deaths?

I Believe That The Native Americans Couldn’t Add Up To The Amount Of Power That The Spanish And Europeans Had Over Them. There Was A Language Barrier And The Native Americans Didn’t Have As Much Advanced Weaponry And Objects That That Could Be Compared To Everything Else That The Spanish And Europeans Had. They Couldn’t Communicate Well And Were Easily Manipulated Into Their Ways And Forced Them To Adjust To The Lifestyle That They Had Laid Out For Them. Though They May Be Powerful In Their Own Way, The Europeans And Spanish Were Way Advance But I Wonder What Had Started So Much Hated Towards Certain Powers?

I think if the natives were more united with each other, they would’ve stopped the Europeans. Despite the superior weapons the Europeans had, having an empire/society that wasn’t unified was far more deadly. With a unified empire, the natives could’ve easily won the battles by outnumbering the Europeans. It is proven by many wars, that quantity is better than quality. Quantities have their own qualities and advantages in war.

What would happen if the Aztec won and didn’t fall? Why did some people resented the Aztecs? Did the Aztec treated them badly to the point that they rebel?

Why did so much explorers search though the Americas for riches, yet a majority who did previously didn’t find anything even after searching all throughout the eastern portion of the Americas? Did they do this gamble because the reward, if they did strike riches, would outweigh their chances of finding nothing?

Why did the Spanish hate the Native Americans so much? The French had gone along pretty well with them because of trade and the Spanish could’ve done the same. Although, the Spanish were treating them poorly and had even created the caste system.

Who was most affected by The Columbian Exchange? and how did diseases affect the columbian exchange?

What did the French see in the Native Americans (other than the profitable fur trade) that led them to treat the natives with respect? How does this differ with the Spanish Conquistadors, as well as some of the other European conquerers? As “The Black Legend” spread around, did some other Spaniards side with Las Casas’s point of view and oppose the mistreatment of Native people?

How was the Pueblo Revolt successful? Was everyone that are non-christian considered below the Europeans? How did Africans become slaves in the Americas?

Millions of Native Americans didn’t stop a few thousand European conquers due to the fact that they were dying off so quickly. Natives decline in population was mainly impacted by the several diseases that the Europeans brought along. Diseases such as smallpox, diphtheria, typhus, measles, and influenza seemed to have a greater role than the Spanish force of arms had itself. Not only were there diseases that took part in the decreasing population of natives, but civil wars as well. For example, during the time of the fall of the Inca, the Spanish were more advanced with their military gear, including armor, horses, and weapons, overpowered the siege of the warfare. Therefore, resulting in many Native Americans to die because of the lack of preparedness. However, I do wonder, did Europeans bring the diseases on purpose to kill off natives as a strategic way to gain power over the cities? Or was it just something that happened coincidentally that acted in their favor instead of the Native Americans?

Why did the Europeans thought it was right to mistreat the Native Americans? Because before the Europeans arrive to takeover the Inca Empire and Aztec Empire they both admired the wealth of the Empire’s, and its power, yet once they finally took over they finally had the wealth and the power. But I guess that wasn’t enough for them, so they decided to take advantages of the Natives for labor and change their ways, because they were different, and until they die out.

What happened to Las Casas after he wrote and published this book that exposed the true intentions and actions of the Spainards in America, as it was mentioned that this is the book that gave rise to the Black Legend, how did the Spanish Crown react to this book, and what happened Las Casas if or when he returned back to Spain?

Before the fall of the Aztec Empire, Cortés and his men were astonished by the incredible gardens and temples in the city, but they were horrified by the practice of human sacrifice that was part of the Aztec religion. Given that information, if they thought that the practice of human sacrifice was awful, why would they think that the encomienda system and their mistreatment of Native Americans were morally right? I think this was because of their view on colonization. They believed that the native people would work for them because of their conquest of the land. Their views on colonization led them to brutally use the native people as slaves, replace the Native leaders with their own royal governors, and extracted the mineral wealth of the continent for their glorification.

I believe that the Native Americans couldn’t add up to the amount of power that the Spanish and Europeans had over them. There was a language barrier and the Native Americans didn’t have as much advanced weaponry and objects that that could be compared to everything else that the Spanish and Europeans had. They couldn’t communicate well and were easily manipulated into their ways and forced them to adjust to the lifestyle that they had laid out for them. Though they may be powerful in their own way, the Europeans and Spanish were way advance but I wonder what had started so much hated towards certain powers?

Why did Europeans seem to see Native Americans as savages rather than people? It seems that they weren’t even considered to be humans to Europeans. Was it because of the way they looked or behaved? Or simply a different lifestyle?