JUMP TO

TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

In the first part of the Civil Rights Movement, change happened because a few people chose to do what was right, even though it was often hard. The days of the great marches led by famous people like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. were still in the future, so it was individual presidents, business leaders, judges, and students who made a difference by choosing to be fair instead of being prejudiced. They made decisions that were not popular, and sometimes even dangerous.

What made these people do what they did? Why did they decide to put their lives on the line and make other people angry so that they could make change happen? Why did they look at injustice and decide that it was up to them to make change? How was it that a few Americans, sometimes only children, got rid of unfair laws and discrimination that had been around for years and years? What was special about them that helped them be successful?

How did these individual people push the Civil Rights Movement forward?

A LONG STRUGGLE FOR JUSTICE

The Civil Rights Movement of marches, boycotts, and great speeches by leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr. that many Americans know about did not suddenly happen. In fact, African Americans had been working for many years to get the same rights as White Americans.

As amazing as it may seem, slavery has been present in the United States longer than it has not. The first slaves were brought to the Virginia Colony in 1619, and the 13th Amendment to the Constitution did not end slavery until after the Civil War in 1865. That’s a total of 246 years! Slavery has been in America 100 years more than it has not. So, it would be wrong to think that the control of millions of people because of their skin color did not have a huge impact on our country.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, three amendments to the Constitution were approved. They ended slavery, gave citizenship to Americans of all races, and gave the right to vote to all men. Together, these three major changes could have been the start of a totally new way of life in the South. However, in 1877 the government decided to bring soldiers home who had been in the South trying to protect former slaves and force White Southerners to change their way of thinking. White leaders in the South took power back and created a system of rules and laws which put them back in control.

The social order of the Old South returned. African Americans were at the bottom of society. They lived in the worst areas of town and had the worst jobs, or lived as hired farmers, living on the farm and always having to pay rent to the White person who owned the land. African Americans could not eat in the same restaurant as White people, swim in the same swimming pools, drink from the same water fountains, or go to the same schools. They could not vote, run for office, and could not change their position in life. African Americans were treated like second-class citizens. It was everywhere, in jobs, schools, government, and even language. For example, White people were used to calling all African American men “boy,” no matter how old they were. This new system became called Jim Crow.

At first, well-known African American leaders tried to improve the lives of their people through education. Booker T. Washington, for example, opened the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, but he was afraid that trying to ask for equality would lead to more violence and problems for African Americans.

Things changed in the 1900s when the Great Migration brought thousands of African Americans to the cities of the North. New leaders in these northern cities began talking about equal rights in public. Among the most famous was W. E. B. Du Bois who started the Niagara Movement. Through the work of Du Bois and great writers like Langston Hughes, the Harlem Renaissance led to the idea of the New Negro, and the real fight for equality was born. With a new feeling of pride and knowing what needed to be done, African American leaders created the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in the early 1900s to fight for their rights in court.

During World War II, another important leader fought for equal rights. A. Philip Randolph, the head of the union of railroad porters, convinced President Franklin Roosevelt to make discrimination illegal at any companies that sold things to the government or army.

When World War II finished, it had been almost a century since slavery had ended. A lot of good had been done, but there was still much more to do.

CIVIL RIGHTS AFTER WORLD WAR II

After World War II, America tried to show the world that countries with free democratic governments were better than countries with dictators and communism. But the Jim Crow system of segregation in the South, and prejudice in other parts of the country showed that even though we said that we were free, millions of Americans didn’t have basic rights. In fact, the leaders of the Soviet Union and communist China threw this in our face every time American politicians said that the Soviet Union and China did not let their people have human rights.

One of the first changes to take place after World War II came in the world of sports. In 1947, the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers baseball team decided to put Jackie Robinson on the field and broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier. Until then, the many talented African American baseball players had to play in the Negro Leagues. As African American fans rushed to see the Dodgers play, other baseball teams followed suit and let African Americans join their own teams.

Another bold move in the early post-war era, was the full integration of the military. In 1948 President Harry Truman’s Executive Order 9981 ended segregation in the military. No longer would there be Whites-Only or Blacks-Only units in the army or air force.

Primary Source: Newspaper

Primary Source: Newspaper

President Truman’s Executive Order 9981 was an important step toward integration in the country. Because he was Commander in Chief of the armed forces, he did not need Congress or the White people of the US to say that this was okay to do.

But baseball and the military were pretty easy to integrate compared to what most people experienced every day in the South. Nothing showed how dangerous the fight for civil rights was more than the murder of Emmitt Till. Till was born and raised in Chicago, and he understood racism, but Emmitt did not grow up learning the harsh rules of the Jim Crow South. While visiting family in Mississippi in 1955, he spoke to 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant, the White owner of a small grocery store. Exactly what happened at the store is not known, but Whites in the area thought that Till had been flirting with Bryant. Several nights later, Bryant’s husband and his half-brother went to the house where Till was staying and took him. They beat him up, shot him and threw him in the Tallahatchie River.

Three days later, Till’s body was found and returned to Chicago where his mother insisted on a public funeral with an open casket so the world would know what had been done to her son. Photographs of Till’s beaten body were published in magazines and newspapers. When people learned about what had happened to Emmitt Till, they started to support the civil rights movement. When an all-White jury in Mississippi decided the men who murdered Till were innocent, the whole country could see how much White power was built into the society of the South. They could also see how Whites used violence and fear to keep African Americans from having equality.

Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Emmitt Till was only a boy when he was killed. His murder brought attention to the Jim Crow system that used violence to keep Blacks separate from Whites.

BROWN v. BOARD OF EDUCATION

One of the first areas of success for Civil Rights activists was in the courts. In 1896 the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision said that segregated schools were legal, so long as they were equal. But segregated schools were never equal. Teachers in White schools were paid more, school buildings for White students were nicer, and more money for teaching supplies was given to White schools. States normally spent 10 to 20 times as much money on the education of White students as they spent on African American students.

In the 1950s, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), led by lawyer Thurgood Marshall, went to court against the segregated public schools of the South, saying that the “separate but equal” law had not been followed. In 1954, in the famous Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka case, the Supreme Court said that “Separate facilities are inherently unequal.” Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote the Court’s decision, and all nine members of the Supreme Court agreed. The Supreme Court had sent a clear message that schools had to integrate.

School leaders in the North followed the Court’s decision, but Whites in the South were angry. The Court had not said they had to integrate right away, but had said that school leaders had to follow their decision “with all deliberate speed.” Ten years after Brown, fewer than 10% of southern public schools had integrated. Instead of opening their schools to African Americans, many White leaders just closed their schools. In one county in Virginia, for example, the White county government stopped sending money to schools. Instead, they gave tax money for students to attend private schools. Then they closed the public schools and turned them into private schools that took only White students. Since the schools were private, they didn’t have to follow the Supreme Court’s order. So, despite the Supreme Court’s decision, it took the work of many brave Americans to actually integrate America’s schools.

Primary Source: Photographs

Primary Source: Photographs

Many White Southerners were angered by the Brown v. Board of Education decision of the Supreme Court.

THE LITTLE ROCK NINE

Three years after the Supreme Court that segregated schools were against the law, a face-off took place in Little Rock, Arkansas. In 1957, nine African American students tried to attend the all-White Central High School. When it was clear that White mobs were going to violently stop the students, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus called up the Arkansas National Guard to stop the students, known as the Little Rock Nine, from going to the school. Then a federal judge declared that stopping the students was illegal. Faubus sent the National Guard soldiers home. When the students tried again to go to the school, they were taken in through a back door. Word of this spread, and a thousand angry White people charged the school. As the police tried to keep the crowd under control, other worried people rushed the students to safety.

Amazed Americans watched on television as violent, White Southerners harassing polite African American children trying to get an education. Television was new in the 1950s, and it had a powerful effect on how people thought and felt about the news. President Eisenhower was forced to act. Eisenhower did not really want to get involved in the civil rights movement, but he was afraid that the Brown decision could lead to a stand-off between the federal government in Washington, DC and state governments. Eisenhower did not believe the individual states had the right to go against the Supreme Court. He ordered the soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division into Little Rock and took control of the Arkansas National Guard so that the governor couldn’t use them to stop the students from attending school. It was the first time federal soldiers were sent to the South since the days of Reconstruction after the Civil War. For the next few months, the African American students went to school with army soldiers protecting them.

The next year, Little Rock city leaders closed the schools. But a year later, the schools were open again. This time both African American and White children attended school together. It was a victory for the Little Rock Nine and for African American students everywhere.

RUBY BRIDGES

Yet another challenge to segregation was made by a little girl. In early 1960, Ruby Bridges was one of six African American children in New Orleans who passed the test to decide if they could go to the all-White William Frantz Elementary School. In the end, only Bridges chose to attend, and US Marshals had to go with her to class every day to protect her from the crowds of angry Whites who didn’t want their children at the same school as African Americans.

Bridges later said, “Driving up I could see the crowd, but living in New Orleans, I actually thought it was Mardi Gras. There was a large crowd of people outside of the school. They were throwing things and shouting, and that sort of goes on in New Orleans at Mardi Gras.” Former United States Deputy Marshal Charles Burks later recalled, “She showed a lot of courage. She never cried. She just marched along like a little soldier, and we were all very, very proud of her.”

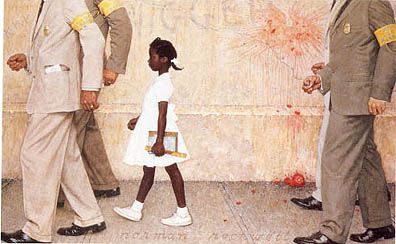

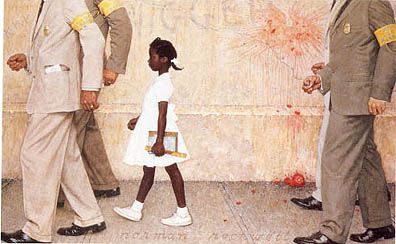

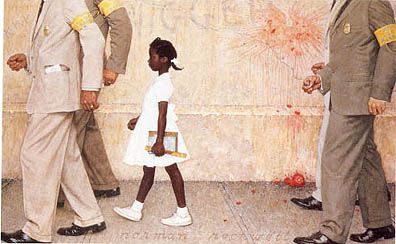

Primary Source: Painting

Primary Source: Painting

Norman Rockwell’s painting, “The Problem We All Live With,” showed how innocent African American students who integrated the schools of the South were, plus the hate and the fight for power between Whites in the South and the US government.

As soon as Bridges entered the school, many White parents pulled their own children out. All the teachers except for one refused to teach while an African American child was enrolled. Only one person agreed to teach Ruby, and that was Barbara Henry from Boston, Massachusetts. For over a year Ruby was in a class all alone with just Henry as her teacher.

The Bridges family suffered for their decision to send her to William Frantz Elementary. Her father lost his job at the gas station where he worked. The grocery store the family went to would no longer let them shop there. Her grandparents, who were sharecrop farmers in Mississippi, were forced off of their land.

Ruby remembers that many others in the community, both African American and White, showed support. Some White families continued to send their children to Frantz. A neighbor gave her father a new job, and local people helped to take care of the kids, watched their house to keep it safe, and walked behind the federal marshals’ car on the trips to school.

Bridges still lives in New Orleans with her husband and their four sons. She now leads the Ruby Bridges Foundation, which she started in 1999 to further “the values of tolerance, respect, and appreciation of all differences.”

JAMES MEREDITH

In 1961 James Meredith applied to the University of Mississippi. He said that it was his civil right to go to the university since it was a state school. Despite the Brown v. Board of Education decision and the fact that the university was supported by all the people who paid taxes, it still had not admitted a single African American student.

In his application, Meredith wrote, “Nobody handpicked me. I believed, and believe now, that I have a Divine Responsibility. I am familiar with the probable difficulties involved in such a move as I am undertaking and I am fully prepared to pursue it all the way to a degree from the University of Mississippi.”

His application was turned down two times. With the help of Medgar Evers of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Meredith went to court. There, he argued that the school had turned him down only because he was an African American. He had a very successful record of military service and had shown that he was a good student. After many lower court cases, the Supreme Court said that their Brown decision was correct, and that Meredith had the right to be admitted to the University.

The Governor of Mississippi, Ross Barnett, insisted that “no school will be integrated in Mississippi while I am your governor,” and the state legislature passed a new law that kept any person from being admitted to the University “who has a crime of moral turpitude against him,” or who had been convicted of any felony crime, or not given a pardon. The same day that it became law, Meredith was accused and found guilty of “false voter registration.”

Clearly, Mississippi’s White leaders were doing anything they could to keep Meredith from going to the university, so President John F. Kennedy decided to step in. With the help of his younger brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, the president ordered US Marshals and army soldiers to go with Meredith on his way to school. When the marshals arrived with Meredith, a mob of angry Whites came to the campus and a riot broke out. During the course of a day, over 100 US soldiers and marshals were hurt, and three people who were not soldiers or marshals were killed. The so-called Battle of Oxford ended the next day and Meredith was allowed into school.

Many of the University students made Meredith’s life difficult. For example, they wouldn’t sit near him and they made noise in his dorm at night to keep him from sleeping. But despite that, and always being isolated from other students, he graduated with a degree in political science.

THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA

The same year Meredith graduated, three African American students became the first to attend the University of Alabama. Vivian Malone Jones, Dave McGlathery, and James Hood had all been turned down because they were African American. But they went to court and a judge ordered that they be admitted.

Alabama’s Governor George Wallace had made a name for himself as a leader who believed in segregation, promising, “Segregation now, Segregation tomorrow, Segregation forever.” When President Kennedy ordered the US Marshals to escort the students to school, Wallace made a show of standing in front of the door to keep them out. Kennedy sent in the army to force Wallace out of the way. When they arrived, Wallace gave a speech promoting his racist ideas, but he finally moved, and the students were able to enroll in the university. It is one of the most remembered standoffs in the fight to let African American students enter the schools and universities of the South.

Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

The stand made by Alabama Governor George Wallace (on the left) at the door at the University of Alabama in 1963 is remembered as an important moment as White Southerners tried to hold on to the segregated school system of the Jim Crow era.

CONCLUSION

The brave decision to let Jackie Robinson play on an all-White baseball team, and his courage in doing so, broke down old barriers in sports. President Truman ended hundreds of years of segregation in the military. The choices of individual students and their families to stand up to hate and prejudice and go to an all-White school was just as brave. Those students could have easily been killed on their way to class. Standing up for African Americans was not popular back then. Millions of White people in the South were proud to say that they were racist and wanted to keep Whites and African Americans apart. Because of that, the decisions by President Eisenhower and President Kennedy to support the students instead of the White leaders who ran those schools was brave as well.

Without these people, the later work of Dr. King, and the Civil Rights marches and protests that most Americans are familiar with, probably would not have happened. So, how did individuals advance the Civil Rights Movement?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The Civil Rights Movement began slowly after WWII with the first big successes coming when the Supreme Court and then a few brave individuals ended school segregation.

African Americans have been working for their civil rights for generations. When slavery ended after the Civil War in 1865, three amendments to the Constitution were ratified that ended slavery, granted former slaves citizenship, and guaranteed voting rights to all men. However, a new system of laws was established in the South by White leaders the blocked these rights. African Americans lived as second-class citizens with no vote.

Segregation was a way of life in the South. African Americans could not eat in restaurants, go to movie theaters, or even drink from the same drinking fountains as Whites. Their children went to segregated schools and they rode in the back of city busses. This system was nicknamed Jim Crow.

In the early 1900s, African Americans had started working against this system, especially during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s.

Some progress was made in the 1940s after World War II. The first African Americans began playing for major league baseball teams. Also, President Truman desegregated the military and eliminated blacks-only units. However, when a young African American boy was murdered in the South, an all-White jury set his White killers free, and it was clear that segregation in the South would be hard to change.

In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled that segregated schools were unconstitutional. This undid an older ruling. Despite their decision, most White leaders in the South refused to integrate their schools.

In Little Rock, Arkansas, nine African American students tried to enroll in high school. When mobs of Whites were going to attack them, President Eisenhower ordered the national guard to escort them to school.

Ruby Bridges became the first African American girl to attend her school when she enrolled in kindergarten. Federal marshals had to escort her to school so she would not be hurt by White mobs.

James Meredith became the first African American to attend the University of Mississippi. President Kennedy ordered the National Guard to escort him to school. For three days there was rioting as Whites tried to keep him out.

At the University of Alabama, the governor tried to stand in the doorway and prevent African Americans from enrolling.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Jackie Robinson: First African American baseball player to play for a major league team.

Emmitt Till: African American teenager from Chicago who was murdered by Whites in 1955 while visiting his family in Mississippi. His murder and open casket funeral brought national attention to the issue of Jim Crow segregation and racism in the South.

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP): Organization dedicated to promoting African American rights through the justice system. It was established in 1909 as part of the Niagara Movement.

Thurgood Marshall: NAACP lawyer who argued the Brown v. Board of Education case and was later appointed to be the first African American justice on the Supreme Court.

Earl Warren: Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in the 1950s and 1960s who pushed the Court to rule favorably on numerous cases related to civil rights.

Little Rock Nine: Group of African American students who integrated the main high school in Arkansas under the protection of the National Guard.

Ruby Bridges: African American girl who was the first to integrate Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans. She became the subject of Norman Rockwell’s painting “The Problem We All Life With.”

James Meredith: First African American student at the University of Mississippi.

George Wallace: Governor of Alabama during the 1960s who was a champion of segregation. His most famous line was “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

![]()

COURT CASES

Plessy v. Ferguson: 1896 Supreme Court case in which the court declared that racially segregated schools and other public facilities were constitutional establishing the “separate but equal” doctrine. It was overturned in the Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954.

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka: 1954 Supreme Court decision that ended segregated schools by overturning the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling.

![]()

EVENTS

Battle of Oxford: Rioting by White citizens and the efforts by US Marshals and army troops to keep the peace at the University of Mississippi when James Meredith became the first African American student to enroll there.

![]()

LAWS

Jim Crow: The nickname for a system of laws that enforced segregation. For example, African Americans had separate schools, rode in the backs of busses, could not drink from White drinking fountains, and could not eat in restaurants or stay in hotels, etc.

Executive Order 9981: Executive order issued by President Truman in 1948 ending racial segregation in the military.

Separate but Equal: Legal doctrine established by the Supreme Court in the Plessy v. Ferguson case that segregated schools and other public institutions were legal so long as they were equal.