TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

Today we call ourselves “the United States,” but this was not always so. When Washington and the Colonial Army effectively secured independence at Yorktown in 1781, most people referred to their new nation as “these United States.”

This may seem like a minor difference, but consider the implications of how we speak of our nation. If we are “these United States,” we must think of ourselves as a collection of individual parts. If we are “the United States,” we are thinking first of the whole, and then noting that it is made up of parts. It is a bit like talking about M&Ms or a bag of M&Ms. In the first case, we are speaking of a plural and in the second a singular entity.

How did this change come about? How did Americans stop thinking of themselves as a collection of individual colonies or states, and start thinking about themselves as a single nation? When did we stop being citizens of New York, Massachusetts, or Rhode Island before being American?

This is the question you will explore here. Why are we THE United States and not THESE United States?

STATE CONSTITUTIONS

The states faced serious and complicated questions about how govern themselves after independence. What did it mean to replace royal authority with institutions based on popular rule? How was popular sovereignty, the idea that the people were the highest authority, to be institutionalized in the new state governments? For that matter, who were the people?

Every state chose to answer these questions in different ways based on distinctive local experiences, but in most cases colonial traditions were continued, with some modifications, so that the governor lost significant power, while the assemblies, the legislative branch that represented the people most directly, became much more important. The new rules created in three states to suggest the range of answers to the question about how to organize republican governments based upon popular rule.

Pennsylvania created the most radical state constitution of the period. Following the idea of popular rule to its logical conclusion, Pennsylvania created a state government with several distinctive features. First, the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776 abolished property requirements for voting as well as for holding office. All adult man who paid taxes were allowed to vote or even to run for office. This was a dramatic expansion of who was considered a political person, but other aspects of the new state government were even more radical. Pennsylvania also became a unicameral government where the legislature only had one body. Furthermore, the office of the governor was entirely eliminated. Radicals in Pennsylvania observed that the governor was really just like a small-scale king and that an upper legislative body, like the House of Lords in Parliament, was supposed to represent wealthy men and aristocrats. Rather than continue those forms of government, the Pennsylvania constitution decided that the people could rule most effectively through a single body with complete legislative power.

Many conservative Patriots viewed Pennsylvania’s new design with horror. When John Adams described the Pennsylvania constitution, he only had bad things to say. To him it was “so democratical that it must produce confusion and every evil work.” Clearly, popular rule did not mean sweeping democratic changes to all Patriots.

South Carolina’s State Constitution of 1778 created new rules at the opposite end of the political spectrum from Pennsylvania. In South Carolina, white men had to possess significant property to vote, and they had to own even more property to be allowed to run for political office. In fact, these property requirements were so high that 90% of all White adults were prevented from running for political office.

This dramatic limitation of who could be an elected political leader reflected a central tradition of Anglo-American political thought in the 1700s. Only individuals who were financially independent were believed to have the self-control to make responsible and reasonable judgments about public matters. As a result poor white men, all women, children, and African Americans, both free and slave, were considered too dependent on others to exercise reliable political judgment. While most of these traditional exclusions from political participation have been ended, age limitations remain largely unchallenged.

The creation of the Massachusetts State Constitution of 1780 offered yet another way to answer some of the questions about the role of “the people” in creating a republican government. When the state legislature presented the voters with a proposed constitution in 1778, it was rejected because the people thought that this was too important an issue for the government to present to the people. If the government could make its own rules, then it could change them whenever it wanted and easily take away peoples’ liberties. Following through on this logic, Massachusetts held a special convention in 1780 where specially elected representatives met to decide on the best framework for the new state government.

This idea of a special convention of the people to decide important constitutional issues was part of a new way of thinking about popular rule that would play a central role in the ratification of the national Constitution in 1787-1788.

THE ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION

While the state constitutions were being created, the Continental Congress continued to meet as a general political body. Despite being the central government, it was a loose confederation and most power was held by the individual states. By 1777 members of Congress realized that they should have some clearly written rules for how they were organized. As a result the Articles of Confederation were drafted and passed by the Congress in November.

This first national constitution for the United States was not particularly innovative, and mostly put into written form how the Congress had operated since 1775.

Even though the Articles were rather modest in their proposals, they were not ratified by all the states until 1781. Even this was accomplished largely because the danger of war demanded greater cooperation.

The purpose of the central government was clearly stated in the Articles. The Congress had control over diplomacy, printing money, resolving controversies between different states, and, most importantly, coordinating the war effort. The most important action of the Continental Congress was probably the creation and maintenance of the Continental Army. Even in this area, however, the central government’s power was quite limited. While Congress could call on states to contribute specific resources and numbers of men for the army, it was not allowed to force states to obey the central government’s request.

The organization of congress itself demonstrates the primacy of state power. Each state had one vote. Nine out of thirteen states had to support a law for it to be enacted. And, any changes to the Articles themselves would require unanimous agreement. In the one-state, one-vote rule, state sovereignty was given a primary place even within the national government. Furthermore, the whole national government consisted entirely of the unicameral Congress with no executive and no judicial organizations.

The national Congress’ limited power was especially clear when it came to money issues. Not surprisingly, given that the Revolution’s causes had centered on opposition to unfair taxes, the central government had no power to raise its own revenues through taxation. All it could do was request that the states give it the money necessary to run the government and wage the war. In 1780, with the outcome of the War for Independence still very much undecided, the central government had run out of money and was bankrupt! As a result, the paper money it issued was basically worthless. To say something is “not worth a continental” is to say it has no value. Clearly, it comes from this time period.

Robert Morris, who became the Congress’ superintendent of finance in 1781, forged a solution to this dire dilemma. Morris expanded existing government power and secured special privileges for the Bank of North America in an attempt to stabilize the value of the paper money issued by the Congress. His actions went beyond the limited powers granted to the national government by the Articles of Confederation, but he succeeded in limiting runaway inflation and resurrecting the fiscal stability of the national government. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Originally known as the Pennsylvania State House, the building housed the Pennsylvania colonial and state governments, as well as the Continental Congress. Both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were signed there. The Liberty Bell hung in its tower (although it is now in a museum across the street).

SUCCESSES UNDER THE ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION

The central failure of the Congress was related to its limited FISCAL POWER. Because it could not impose taxes on the states, the national government’s authority and effectiveness was severely limited. Given this major encumbrance, the accomplishments of the Congress were actually quite impressive. First of all, it raised the Continental Army, kept it in the field, and managed to finance the war effort.

Diplomatic efforts helped the war effort too. Military and financial support from France secured by Congress helped the Americans immeasurably. The diplomatic success of the treaty of alliance with France in 1778 was unquestionably a major turning point in the war. Similarly, the success of Congress’ diplomatic envoys to the peace treaty ending the war also secured major — and largely unexpected — concessions from the British in 1783. The treaty won Americans’ fishing rights in rich Atlantic waters that the British navy could have controlled. Most importantly, Britain granted all its western lands south of the Great Lakes to the new United States.

Although winning these western lands from the British was an important diplomatic victory for the United States, actually having them created new problems. Ownership of this land and how to best settle it was enormously controversial. Before independence, each colony had claimed lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. As part of ratifying the Articles of Confederation, each state had ceded its claim to western land to the national government, but the lure of wealth in the West might lead state leaders to reassert their old claims.

To make matters worse, many Americans had ignored legal restrictions on western settlement, such as the Proclamation of 1763, and simply struck out for new land that they claimed as their own by right of occupation. How could a national Congress with limited financial resources and no coercive power deal with this complex problem? Secondary Source: Map

Secondary Source: Map

Land claims ceded by the first 13 states during the Articles of Confederation Era.

The Congressional solution was a remarkable act of statesmanship that tackled several problems and did so in a fair manner. The Congress succeeded in asserting its ownership of the western lands and used the profits from their sale to pay the enormous expenses associated with settlement such as construction of roads and providing military protection. Second, the Congress established a process for future states in this new area to join the Confederation. The new states would be sovereign and not suffer secondary colonial status. That is, they would be states equal to the original thirteen members.

The actual process by which Congress took control of the area of western lands north of the Ohio River indicated some of its most impressive actions. Congress passed three laws – the Ordinance of 1784, the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, regarding the settlement of this Northwest Territory. Together, these three laws established an admission policy to the United States based on population, organized the settlement of the territory on an orderly rectangular grid pattern that helped make legal title more secure, and prohibited the expansion of slavery to this large region which would eventually include the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

The resolution of a potentially crisis-filled western land policy was perhaps the most outstanding accomplishment of the first national government. A political process for adding new states as equals was created. A partial solution to the national revenue crisis was found. Together these policies fashioned a mechanism for the United States to be a dynamic and expanding society. Most remarkably of all, Congressional western policy put into practice some of the highest Revolutionary ideals that often went unheeded. By forbidding slavery in the Northwest as an inappropriate institution for the future of the United States, the Congress’ achievements should be considered quite honorable. At the same time, however, there were people whose rights were infringed upon by this same western policy. The control of land settlement by the central government favored wealthy large-scale land developers over small-scale family farmers. Furthermore, Native Americans’ claim to a western region still largely unsettled by Whites, was ignored.

THE ECONOMIC CRISIS OF THE 1780s

The economic problems faced by the Congress deeply affected the lives of most Americans in the 1780s. The war had disrupted much of the American economy. On the high seas, the British navy had superiority and destroyed most American ships, crippling the flow of trade. On land, where both armies regularly stole from local farms in order to find food, farmers suffered tremendously.

When the fighting came to an end in 1781, the economy was in a shambles. Exports to Britain were restricted. Further, British law prohibited trade with Britain’s remaining sugar colonies in the Caribbean. Thus, two major sources of colonial-era commerce were eliminated. A flood of cheap British manufactured imports that sold at lower prices than comparable American goods made the post-war economic slump worse. Finally, the high level of debt taken on by the states to fund the war effort added to the economic crisis by helping to fuel rapid inflation.

This crisis was a grave threat to individuals, as well as to the stability and future of the young republic. Independence had been declared and the war had made that a reality, but now the new republican governments, at both the state and national level, had to make difficult decisions about how to respond to serious economic problems. Most state legislatures passed laws to help ordinary farmers deal with their high level of debt. Repayment terms were extended and imprisonment for debt was relaxed.

However, the range of favorable debtor laws passed by the state legislatures in the 1780s outraged those who had extended loans and expected to be paid, as well as political conservatives. Political controversy about what represented the proper economic policy mounted and approached the boiling point. As James Madison of Virginia noted, the political struggles were primarily between “the class with, and [the] class without, property.” Just as the republican governments had come into being and rethought the meaning of popular government, the economic crisis threatened their future.

SHAYS’ REBELLION

The crisis of the 1780s was most intense in the rural and relatively newly settled areas of central and western Massachusetts. Many farmers in this area suffered from high debt as they tried to start new farms. Unlike many other state legislatures in the 1780s, the Massachusetts government didn’t respond to the economic crisis by passing pro-debtor laws. Such laws included provisions for forgiving debt and printing more paper money. More currency in circulation would have driven the value of money and made it less expensive for debtors to pay off their loans. Without such laws on the books, local sheriffs seized many farms. Worse, it was not uncommon for debtors to be taken to court. If they could not pay, they would be thrown in prison until they did. Of course, it is hard to manage a farm and raise any money from prison, so both the wealthy merchants of Boston who had extended the loans and the courts were hated in western Massachusetts.

These conditions led to the first major armed rebellion in the post-Revolutionary United States. Once again, Americans resisted high taxes and unresponsive government that was far away. But this time it was Massachusetts’s settlers who were angry with a republican government in Boston, rather than with the British government across the Atlantic.

The farmers in western Massachusetts organized their resistance in ways similar to the American Revolutionary struggle. They called special meetings of the people to protest conditions and agree on a coordinated protest. This led the rebels to close the courts by force in the fall of 1786 and to liberate imprisoned debtors from jail.

Soon events flared into a full-scale revolt when the resistors came under the leadership of Daniel Shays, a former captain in the Continental Army. This was the most extreme example of what could happen in the tough times brought on by the economic crisis. Some thought of the Shaysites (named after their military leader) as heroes in the direct tradition of the American Revolution, while many others saw them as dangerous rebels whose actions might topple the young experiment in republican government.

James Bowdoin, the governor of Massachusetts, was clearly in the latter group. He organized a military force funded by eastern merchants, many of whom would benefit if the farmers were forced to pay off their debts, to confront the rebels. This armed force crushed the movement in the winter of 1786-1787 as the Shaysites fell apart when faced with a strong army organized by the state. While the rebellion disintegrated quickly, the underlying social forces that propelled such dramatic action remained. The debtors’ discontent was widespread and similar actions occurred on a smaller scale in Maine (then still part of Massachusetts), Connecticut, New York, and Pennsylvania among others places.

While Governor Bowdoin had acted decisively in crushing the rebellion, the voters turned against him in the next election. Perhaps rightly, the voters believed that the state’s wealthy few were running the government and ignoring the needs of the masses. This high level of discontent, popular resistance, and the election of pro-debtor governments in many states threatened the political notions of many political and social elites. Shays’ Rebellion demonstrated the high degree of internal conflict lurking beneath the surface of post-Revolutionary life.

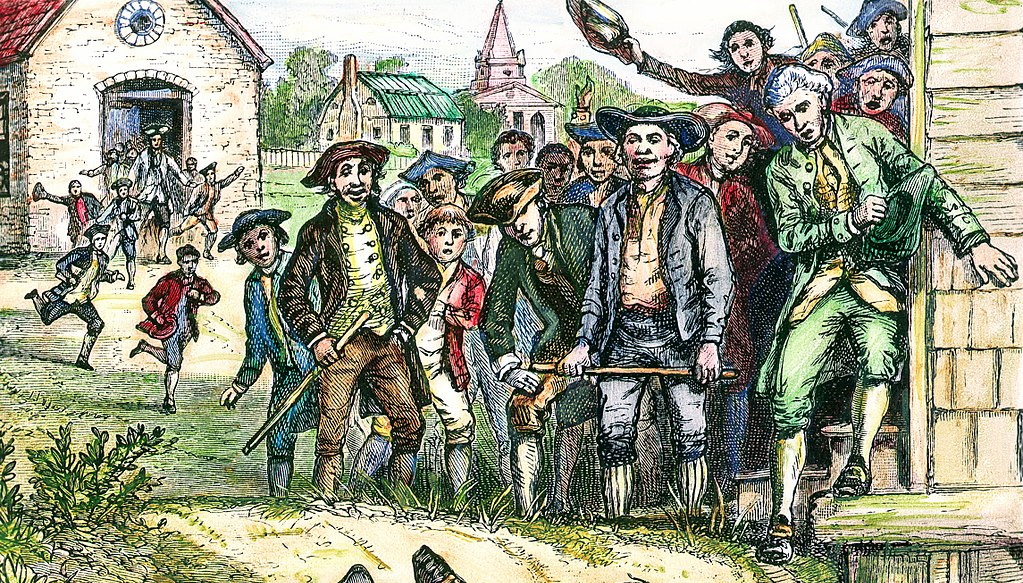

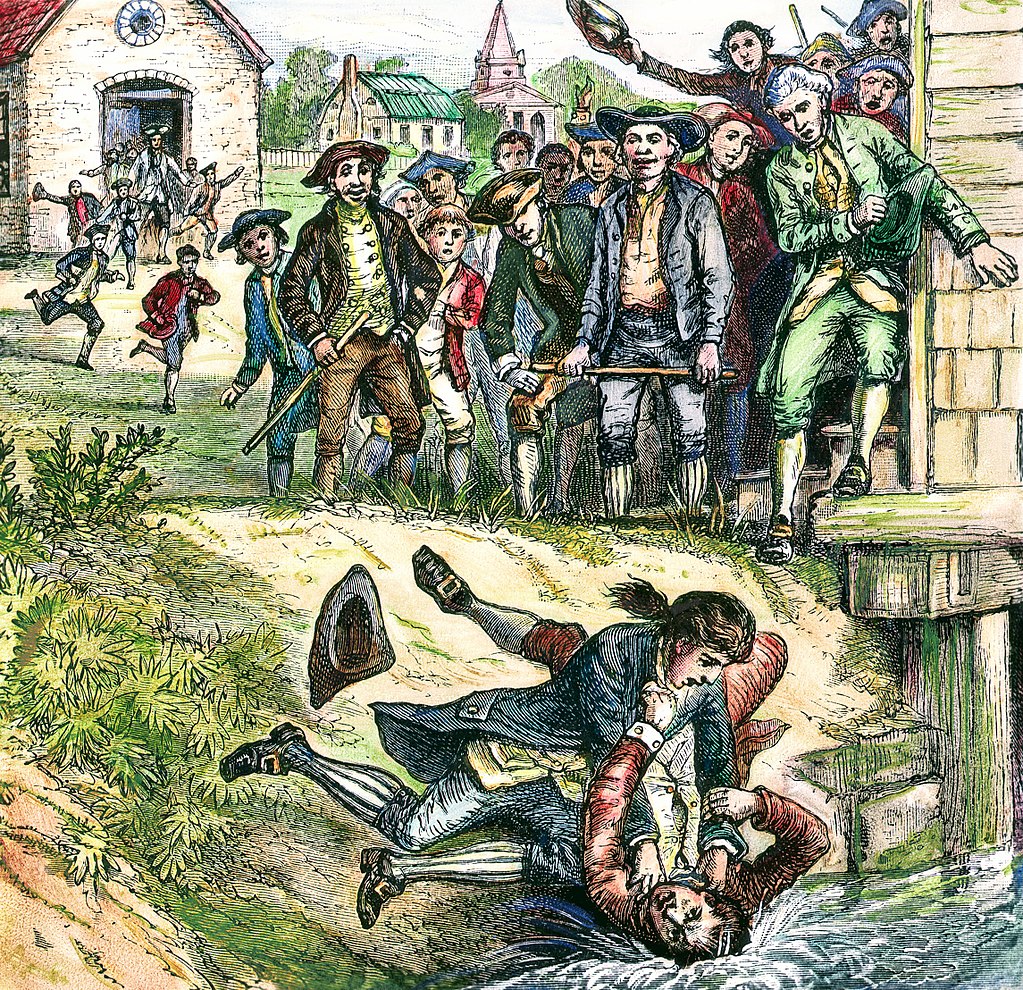

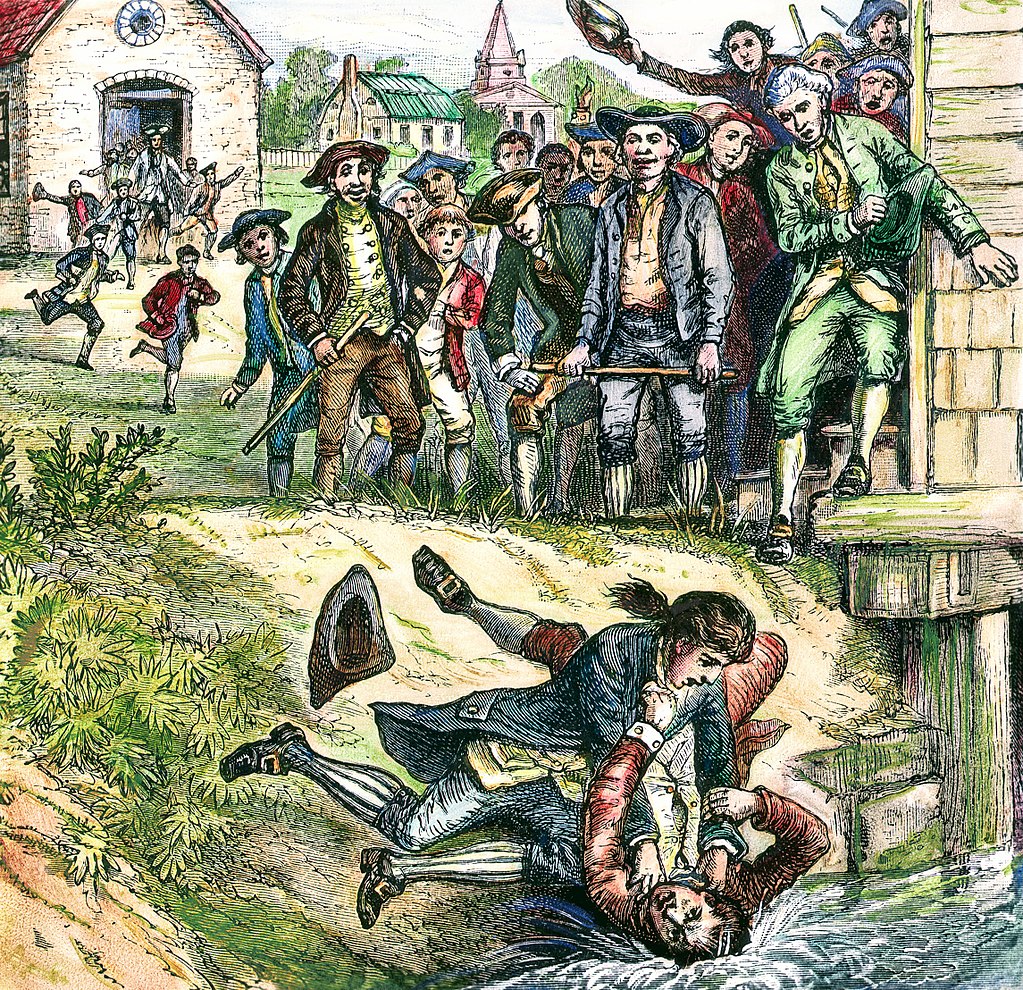

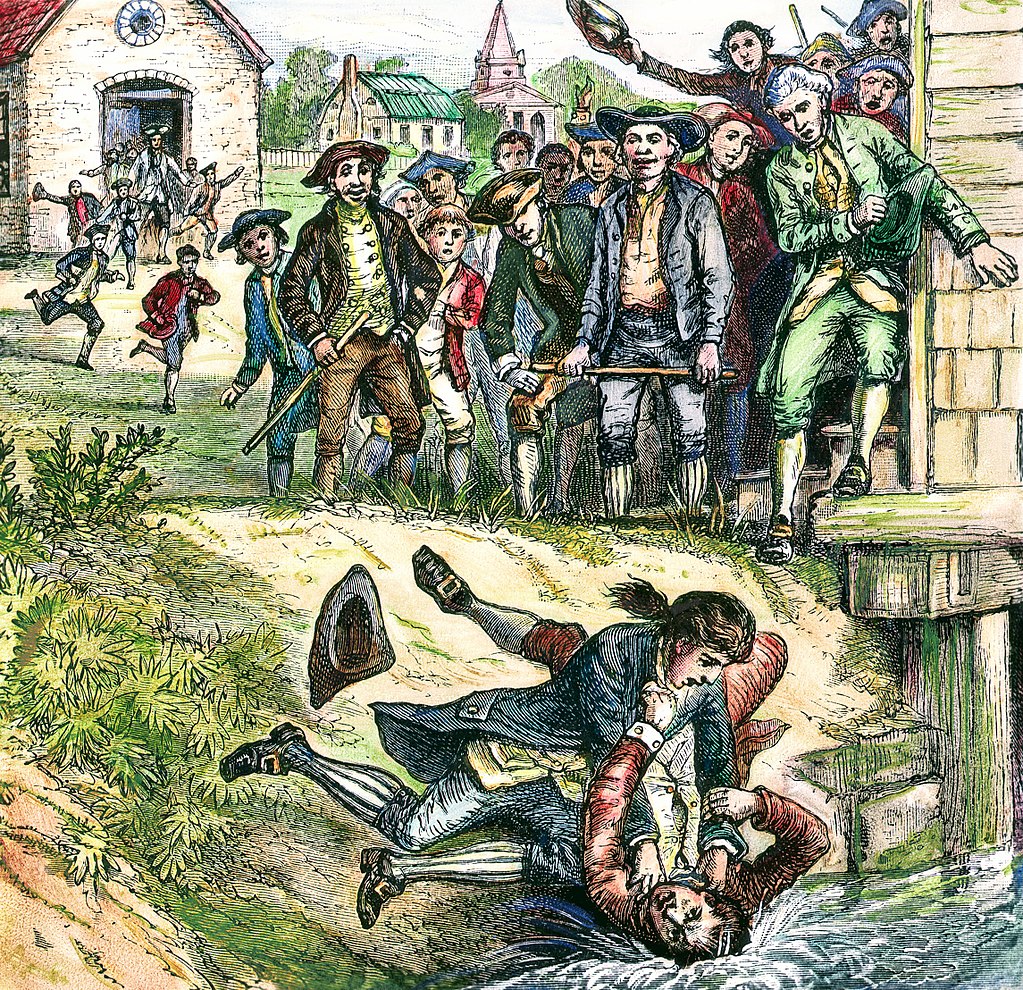

In the end, 4,000 people signed confessions acknowledging participation in the events of the rebellion in exchange for amnesty. Several hundred participants were eventually indicted on charges relating to the rebellion, but most of these were pardoned. Eighteen men were convicted and sentenced to death, but most of these were overturned on appeal, pardoned, or had the sentences commuted. Only two men were ever hanged for their participation in the rebellion. Secondary Source: Illustration

Secondary Source: Illustration

One artist’s impression of Shaysites attacking the courts.

Shays himself was pardoned in 1788 and returned to his farm but was vilified in the Boston press. He moved to the New York where he died poor and obscure in 1825.

Thomas Jefferson was serving as ambassador to France at the time and refused to be alarmed by Shays’ Rebellion. He argued in a letter to James Madison on January 30, 1787 that occasional rebellion serves to preserve freedoms. “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure.” It is one of his most frequently quoted lines, although his political insights were probably incorrect.

More astute, was Shay’s former commander, George Washington, now in retirement at Mount Vernon, Virginia. He had been calling for constitutional reform for many years. When his friend Henry Lee wrote and asked him to use his influence to calm the protestors, he replied, “You talk, my good sir, of employing influence to appease the present tumults in Massachusetts. I know not where that influence is to be found, or, if attainable, that it would be a proper remedy for the disorders. Influence is not government. Let us have a government by which our lives, liberties, and properties will be secured, or let us know the worst at once.” As Washington knew, the Articles of Confederation were not up to the task of preserving the liberties he and his fellow Patriots had won in the Revolution.

CONCLUSION

Most Americans forget that between the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the start of George Washington’s presidency 13 years had passed. Going from a collection of colonies to a unified nation under the constitutional system of government we are familiar with today was a long, complicated, controversial and occasionally violent process.

We may despair when hearing the news of failed nations around the world and think that they would be better off if they just followed our example. However, we were no better than most other people at figuring out how to create a “more perfect union.”

What happened that brought us around? What made it possible for 13 separate states to realize they needed to be truly unified in order to survive? What do you think? How did we become THE United States and not THESE United States?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: For the first few years of American independence, the federal government was weak and ineffective at dealing with major problems. A rebellion in Massachusetts eventually pushed leaders to seek a new system of government.

During the War for Independence the states and Congress formed new systems of government. These formed the basis for ideas that would eventually become part of the Constitution.

The national government was organized under a set of rules called the Articles of Confederation. It emphasized state power, giving only limited responsibility to the national congress. This was because the Revolution had been prompted by conflicts with a powerful national government in Britain that Americans believed had too much authority. Having a weak central government led to problems down the road.

There were some important political agreements made during the Articles of Confederation government. Most notably, Congress agreed to a set of laws laying out the process for the lands of the Old Northwest (today’s Midwest) to become states. Within these laws were the seeds of the Civil War since they banned slavery in the territory. The laws ignored Native Americans.

An economic crisis in the 1780s increased social problems and showed the weaknesses of the government. In Massachusetts, poor farmers could not afford to pay back loans and found themselves in danger of losing land or going to debtor’s prison. Daniel Shays led a rebellion of these farmers against that state government. His rebellion failed, but it showed the rift between the wealthy who dominated government, and the people. It also showed the need for a strong federal government to maintain domestic security.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Daniel Shays: Farmer and former Revolutionary War soldier who organized a rebellion in Western Massachusetts in 1786-87. He and his followers were upset about economic inequalities and debt laws that disadvantaged farmers.

Shaysites: Followers of Daniel Shays.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Unicameral: A legislature with only one group or body of representatives.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Northwest Territory: Area that today includes Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin.

![]()

EVENTS

Economic Crisis of the 1780s: Period after the conclusion of the War for Independence characterized by unemployment, debt, a stagnant economy and social and political upheaval. Hamilton’s economic plans were designed to address this its problems.

Shay’s Rebellion: Uprising in Western Massachusetts led by Daniel Shays in 1786-87. Farmers were upset about economic conditions and debt laws and closed down courthouses to prevent repossession of lands and debtors prison convictions.

![]()

LAWS & RESOLUTIONS

Constitution: Document that outlines the form and function of the United States government. Written in 1787, it has been amended less than 30 times.

Articles of Confederation: The plan for government created during the War for Independence. It featured a unicameral legislature, no executive, and favored state power over federal power. It proved ineffective and was replaced by the Constitution.

Ordinance of 1784, Land Ordinance of 1785 and Northwest Ordinance of 1787: Laws that outlined the process of settlement of the Northwest Territory. They provided for an orderly, rectangular pattern of land division, set aside land for schools, and banned slavery.

Study on Quizlet (Readings 1 & 2 Combined)