TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

As children, everyone learns about government. We teach young students the names presidents and how to pledge allegiance to their flag. As we grow, we learn more about the precise nature of our system. We learn about different branches of government and how that system has changed over time. Once we are adults, we participate in that system by voting, serving on juries, and paying taxes.

However, did you ever stop to consider why our government has authority over our lives? In some places and times governments derived their power from god. In Europe this was called divine right. In ancient Egypt, the pharaoh was a god himself. But our system has no such foundation. God does not select our presidents, legislators or judges. And this fact reveals a great deal about our beliefs about power and society, or perhaps more accurately, it reveals a great deal about the beliefs of the leaders of the colonies in 1776.

Where does government’s power come from?

THE FIRST CONTINENTAL CONGRESS

Americans were fed up. The Intolerable Acts were more than the colonies could stand.

In the summer that followed Parliament’s attempt to punish Boston, sentiment for the patriot cause increased dramatically. The printing presses at the Committees of Correspondence were churning out volumes and the message of resistance spread across the colonies.

It had been nearly ten years since the Stamp Act Congress had assembled and there was agreement that this new quandary warranted another intercolonial meeting. Thus, in September 1774, the First Continental Congress convened at Carpenter’ Hall in Philadelphia.

This time participation was better. Only Georgia withheld a delegation. Sam and John Adams from Massachusetts were present, as was John Dickinson from Pennsylvania. Virginia selected Richard Henry Lee, George Washington, and Patrick Henry.

In the end, the voices of compromise carried the day. Rather than calling for independence, the First Continental Congress passed a Declaration and Resolves, which called for a boycott of British goods to take effect in December 1774. It requested that local Committees of Safety enforce the boycott and regulate local prices for goods. These resolutions adopted by the Congress did not endorse any legal power of Parliament to regulate trade, but consented, nonetheless, to the operation of acts for that purpose.

The delegates at the First Continental Congress did not outright reject the right of the king to make laws for the colonies, but did draft a petition to the king requesting the repeal of the Intolerable Acts.

Benjamin Franklin carried the petition to England and on January 19, 1775, the petition was presented to the House of Commons by Lord North, and was also presented to the House of Lords the following day. Unfortunately it arrived mixed among letters, official reports and other messages from the colonies and Parliament gave it little attention. Likewise, the King never gave the Colonies a formal reply to their petition.

A plan introduced by Joseph Galloway of Pennsylvania proposed an imperial union with Britain. Under this program, all acts of Parliament would have to be approved by an American assembly to take effect. Such an arrangement, if accepted by London, might have postponed revolution. But the delegations voted against it by a single vote.

One decision by the Congress, often overlooked in importance, was its decision to reconvene in May 1775 if their grievances were not addressed. This was a major step in creating an ongoing intercolonial decision making body.

When Parliament and the King ignored the Congress, the colonial leaders reconvened the next May, but by this time boycotts were no longer a major issue. The Second Continental Congress, however, would grapple with the spilling of blood at Lexington and Concord. Primary Source: Book

Primary Source: Book

A copy of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, published in 1776. The Roman numeral date is at the bottom: MDCCLXXVI.

THOMAS PAINE’S COMMON SENSE

Americans did not break ties with Britain easily.

Despite all the hardships, the majority of colonists had been reared since birth to believe that England was to be loved and its monarch revered.

Change is scary, and the well-informed colonists knew about the harsh manner the British employed with Irish rebels.

A revolution could bring mob rule, and no one, not even the potential mob, wanted that.

Furthermore, despite taxes, times were good. The average American was better off in 1776 than the average Briton.

Yet there were the terrible injustices the colonists could not forget. Americans were not all in agreement about what course of action to take, but arguments for independence were growing. Thomas Paine, who arrived in America only a year before the war began, would provide the extra push.

Paine’s book, Common Sense, was an instant best-seller. Published in January 1776 in Philadelphia, nearly 120,000 copies were in circulation by April. Paine’s brilliant arguments were straightforward. He argued for two main points. First, the colonies should be independent from England and second, the new nation should be democratic republic with elected leaders. Primary Source: Painting

Primary Source: Painting

King George III, painted by Johann Zoffany in 1771

Paine avoided flowery prose. He wrote in the language of the people, often quoting the Bible in his arguments. Most people in America had a working knowledge of the Bible, so his arguments rang true. Paine was not religious, but he knew his readers were. King George was “the Pharaoh of England” and “the Royal Brute of Great Britain.” His ideas touched a nerve in the American countryside.

Beside attacks on George III, he called for the establishment of a republic. Even patriot leaders like Thomas Jefferson and John Adams condemned Paine as an extremist on the issue of a post-independence government. Still, Common Sense advanced the patriot cause. It made no difference to the readers that Paine was a new arrival to America. Published anonymously, many readers attributed it to John Adams, although he denied involvement.

In the end, his ideas were indeed common sense for most Americans. Why should tiny England rule the vastness of a continent? How can colonists expect to gain foreign support while still professing loyalty to the British king? How much longer should Americans stand for the repeated abuses of the Crown? As the summer of 1776 drew near, many of Paine’s readers turned toward the cause of independence.

THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE

For the first few months after war broke out at Lexington and Concord, the Patriots carried on their struggle in an ad-hoc and uncoordinated manner. They had seized arsenals, driven out royal officials, and besieged the British army in the city of Boston. On June 14, 1775, the Second Continental Congress voted to create the Continental Army out of the militia units around Boston and appointed George Washington of Virginia as commanding general.

On July 6, 1775, Congress approved a Declaration of Causes outlining the rationale and necessity for taking up arms in the Thirteen Colonies and two days later they extended the Olive Branch Petition to the British Crown as a final attempt at reconciliation, however, it was received too late to do any good.

Although the Second Continental Congress had no explicit legal authority to govern, the delegates assumed all the functions of a national government such as appointing ambassadors, signing treaties, raising armies, appointing generals, borrowing money, issuing paper money and disbursing funds. However, a lack of legal authority limited the Congress’s ability to take action. Although the delegates were moving towards declaring independence, many delegates lacked the authority from their home governments to take such a drastic action.

Advocates of independence moved to have reluctant colonial governments revise instructions to their delegations, or even replace those governments which would not authorize independence. On May 10, 1776, Congress passed a resolution recommending that any colony with a government that was not inclined toward independence should form one that was. On May 15, they adopted a more radical preamble to this resolution, drafted by John Adams, which advised throwing off oaths of allegiance and suppressing the authority of the Crown in any colonial government that still derived its authority from the Crown.

That same day, the Virginia Convention instructed its delegation in Philadelphia to propose a resolution that called for a declaration of independence, the formation of foreign alliances, and a confederation of the states. The resolution of independence was delayed for several weeks, as advocates of independence consolidated support in their home governments but on June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee offered a resolution before the Congress declaring the colonies independent. He also urged Congress to resolve “to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances” and to prepare a plan of confederation for the newly independent states. Lee argued that independence was the only way to ensure a foreign alliance, since no European monarchs would deal with America if they remained Britain’s colonies.

The delegates recognized the necessity of proving their credibility, especially to potential European allies, so before formally adopted the resolution of independence, Congress creating three overlapping committees to draft the Declaration, a Model Treaty, and the Articles of Confederation to outline the form of government that would guide the new nation.

The committee appointed to draft the declaration, consisting of John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut. The committee left no minutes, so there is some uncertainty about how the drafting process proceeded and contradictory accounts were written many years later by Jefferson and Adams. What is certain is that the committee discussed the general outline which the document should follow and decided that Jefferson would write the first draft.

The committee in general, and Jefferson in particular, thought that Adams should write the document, but Adams persuaded the committee to choose Jefferson and promised to consult with him personally. The committee presented Jefferson’s draft to the full Congress on June 28, 1776. At that point, the title of the document was “A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress assembled.”

After a long day of speeches on July 1, each colony cast a single vote, as was the custom of the Congress. The delegation for each colony numbered from two to seven members, and each delegation voted amongst themselves to determine the colony’s vote. Pennsylvania and South Carolina voted against declaring independence. The New York delegation abstained, lacking permission to vote for independence. Delaware cast no vote because the delegation was split between Thomas McKean who voted yes and George Read who voted no. The remaining nine delegations voted in favor of independence. Edward Rutledge of South Carolina was opposed to Lee’s resolution for independence, and moved that a final vote be postponed until the following day in order to give time unanimous consent. Secondary Source: Engraving

Secondary Source: Engraving

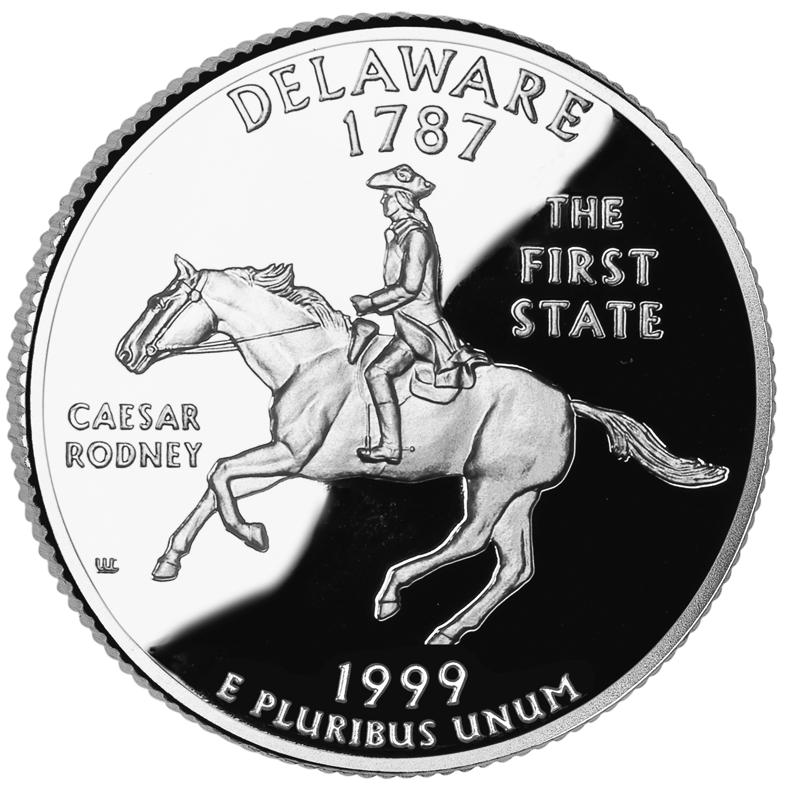

Delaware chose to feature Ceasar Rodney riding to vote for independence on their quarter in 1999.

On July 2, South Carolina reversed its position and voted for independence. In the Pennsylvania delegation, Dickinson and Robert Morris abstained, allowing the delegation to vote three-to-two in favor of independence. The tie in the Delaware delegation was broken by the timely arrival of Caesar Rodney, who, road 70 miles during the night through a thunderstorm to Philadelphia and arrived in time to vote for independence. The New York delegation abstained once again since they were still not authorized to vote for independence, although they were allowed to do so a week later by the New York Provincial Congress. The resolution of independence had been adopted with twelve affirmative votes and one abstention. With this, the colonies had officially severed political ties with Great Britain.

John Adams predicted in a famous letter, written to his wife on the following day, that July 2 would become a great American holiday. He wrote, “I am apt to believe that [Independence Day] will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.” He did not foresee that Americans would instead celebrate Independence Day on the date when the announcement of that act was finalized.

After voting in favor of the resolution of independence, Congress turned its attention to the committee’s draft of the declaration. Over the next two days of debate, they made a few changes in wording and deleted nearly a fourth of the text and, on July 4, 1776, the wording of the Declaration of Independence was approved and sent to the printer for publication. Secondary Source: Painting

Secondary Source: Painting

This famous depiction of the Declaration of Independence is a 12-by-18-foot work by American John Trumbull. Trumbull painted many of the figures in the picture from life, and visited Independence Hall to depict the chamber where the Second Continental Congress met. It hangs in the rotunda of the United States Capitol Building in Washington, DC.

WHAT THE FOUNDING FATHERS SAID

The Declaration of Independence, despite being shortened by Congress, is quite long. It opens by stating why the delegates believed a written declaration was necessary. They wrote, “When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.”

Then, the Declaration continues to its preamble, containing perhaps the most famous phrases in American history. The preamble justified their rebellion. Dense with Enlightenment ideas, it claims that revolution is justified when government harms natural rights. Jefferson’s words, inspired by John Locke, are familiar to most Americans even today.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.”

The Declaration goes on to itemize the various injustices the delegates believed showed the way their government had violated their natural rights. Among the long list are closing trade, quartering troops, imposing taxes without representation, and eliminating jury trials.

THE SIGNATURES

The first and most famous signature on the engrossed copy was that of John Hancock, President of the Continental Congress. When asked why he signed his name so large, it is said that he replied, “So King George III could read it without his glasses.” Two future presidents, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, and a father and great-grandfather of two other presidents, Benjamin Harrison, signed their names. Edward Rutledge, age 26, was the youngest signer. Benjamin Franklin was the oldest at age 70. Altogether, fifty-six men penned their names. If the American effort was successful, they would be hailed as heroes. If it failed, they would be hanged as traitors. Benjamin Franklin drove home to point in his usual way, giving posterity a quote to remember, quipping, “We must, indeed, all hang together or, most assuredly, we shall all hang separately.” Primary Source: Signature

Primary Source: Signature

John Hancock’s signature as it appears at the bottom of the Declaration of Independence. It was so large and now so famous, that if someone asks for your John Hancock, they are asking for your signature.

CONCLUSION

Thomas Jefferson and the delegates to the Second Continental Congress that declared American independence were strongly influenced by the writers and philosophers of the Enlightenment. The Declaration of Independence they signed is one of the world’s best encapsulations of the ideas of the Age of Reason, and in laying out their justification for revolution, they explained what they believed is the proper source for any government’s authority.

What do you think? Why do governments have power?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: American leaders did not want to declare independence right away and tried unsuccessfully to resolve their differences with the government in England. The Declaration of Independence laid out the philosophical reasons for independence and remains a seminal document in American history.

Leaders from the colonies gathered in Philadelphia in 1774 at the First Continental Congress to try to find ways to negotiate with the British government and solve their growing problems. They wrote a petition to the King and resolved to meet again. Their petition was ignored by both Parliament and the King.

Thomas Paine wrote a bestselling book making the case for independence entitled Common Sense. He used enlightenment ideas to explain why the British government had no moral authority over the colonies.

When colonial leaders met in 1776 at the Second Continental Congress, fighting had already begun in Boston. This time, the delegates voted to declare independence. They appointed a committee to write a document explaining their justification for this bold move. Ben Franklin, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson all served on the committee. Jefferson wrote most of the document.

The Declaration of Independence included some of the most important ideas about the meaning of the United States. In it, the Founding Fathers declared that “all men are created equal.”

John Hancock was the president of the Second Continental Congress and signed it first. Washington did not sign the document. He had been appointed to lead the Continental Army.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Thomas Paine: Author of Common Sense, a pamphlet that convinced many Americans to support independence.

George Washington: Virginia planter, surveyor, officer in the Seven Years War, leader of the Continental Army in the Revolution, President of the Constitutional Congress and First President of the United States.

Richard Henry Lee: Virginia delegate to the Second Continental Congress who proposed the resolution to declare independence.

Thomas Jefferson: Author of the Declaration of Independence and later third president.

John Hancock: Boston Patriot who served as President of the Second Continental Congress and was the first signer of the Declaration of Independence. His signature is much larger than the others and is now famous.

![]()

DOCUMENTS

Declaration and Resolves: Resolution passed in 1774 by the First Continental Congress calling for a boycott of British goods.

Petition to the King: Letter to the King and Parliament passed by the First Continental Congress in 1774 asking for repeal of the Intolerable Acts.

Common Sense: Pamphlet authored by Thomas Paine in 1776 that convinced many Americans to support independence.

Declaration of Causes: 1775 declaration passed by the Second Continental Congress explaining why the colonies were fighting against the British government. It did not declare independence.

Olive Branch Petition: Final attempt by the Second Continental Congress in 1775 to find a peaceful resolution to problems between the colonies and the British government. It was ignored by both Parliament and the King.

Declaration of Independence: Statement passed by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776 officially stating that the United States was independent from Britain.

When in the Course of human events…: Opening words of the Declaration of Independence.

Preamble to the Declaration of Independence: Paragraphs of the Declaration of Independence that contains the lines “all men are created equal” and “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

![]()

EVENTS

First Continental Congress: Meeting of leaders from the colonies in 1774. Prompted by the Stamp Act, they passed the Declaration of Resolves and initiated a boycott of British goods. They also sent the Petition to the King.

Second Continental Congress: Meeting of colonial leaders in 1775 and 1776. They declared independence.

July 4, 1776: America’s Independence Day.