TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

The price of living in a capitalist society is that there will always be economic winners and losers. While we have the opportunity to become rich, we know that there will also always be poverty. But is this true? Why can’t a wealthy nation like ours, rich with natural resources, a stable government, and innovated people find a way to end poverty?

In the 1960s, President Lyndon Johnson set out to do just that. After stepping into the presidency when John F. Kennedy was assassinated, Johnson described for Americans a Great Society. In this society, there would be no poverty. People would be able to pay for healthcare, have safe food, safe cars, safe homes, access to great art and music, and people from all over the world would be able to come to the United States to join and participate in this utopian nation.

For some it seemed too idealistic, but the 1960s was a time of change and Americans were eager for idealism. Johnson was able to convince Congress to enact his plans, and won the presidency himself in a tremendous landslide victory in 1964.

Of course, there is still poverty today, over half a century later, so we know that Johnson did not succeed in ending poverty. But perhaps that was not the fault of his programs and ideas, but rather other circumstances at the time.

What do you think? Can we end poverty?

THE ASSASSINATION OF PRESIDENT KENNEDY

Ask any American who was over the age of eight in 1963 the question: “Where were you when President Kennedy was shot?” and a complete detailed story is likely to follow. The death of the young, dynamic president is one of the defining moments of the 1960s, and one that people who lived through it have never forgotten.

Although his public advocacy for civil rights had won him support in the African American community, and his steely performance during the Cuban Missile Crisis had led his overall popularity to surge, Kennedy understood that he had to solidify his base among White Southerners to secure his reelection in 1964. On November 21, 1963, he accompanied Vice President Lyndon Johnson to Texas to rally his supporters in that large state.

President Kennedy’s motorcade route through Dallas on November 22 was planned to give him maximal exposure to Dallas crowds before his arrival at a luncheon with civic and business leaders in the city. The planned motorcade route was widely reported in Dallas newspapers several days before the event for the benefit of people who wished to view the motorcade, but tragically gave Kennedy’s assassin a chance to plan his attack.

At about 11:40am, the presidential motorcade left for the trip through Dallas. By the time the motorcade reached Dealey Plaza, Kennedy was only five minutes away from the planned destination. At 12:30 p.m., as Kennedy’s uncovered limousine entered Dealey Plaza, a reported three shots were fired at Kennedy. Seriously injured, Kennedy was rushed to Parkland Hospital where he was pronounced dead. Primary Source: Newspaper

Primary Source: Newspaper

The headline of The Boston Globe captured the sentiments of the nation. Kennedy’s death shocked the nation.

Vice-President Johnson had been riding two cars behind Kennedy in the motorcade and was not injured. He took the oath of office and became president. At his side was a grieving Jaqueline Kennedy. The photograph of the moment is one of the most heart-wrenching in American presidential history. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

The tragic image of Jaqueline Kennedy standing next to Lyndon Johnson as he took the oath of office aboard Air Force One. Johnson refused to leave Dallas until Kennedy’s body and the former First Lady were aboard.

The gunfire that killed Kennedy appeared to come from the upper stories of the Texas School Book Depository building. Lee Harvey Oswald, an employee at the depository and a trained sniper was charged with the murders of President Kennedy and Dallas police officer J.D. Tippit. Oswald denied shooting anyone, and claimed he was being framed because he had lived in the Soviet Union. Oswald’s case never came to trial because he was shot and killed two days later by Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby while being escorted from Dallas Police Headquarters to the County Jail. Arrested immediately after the shooting, Ruby said he had been distraught over the Kennedy assassination and sought to avenge the president’s death.

News of the president’s death shocked the nation. Men and women wept openly. People gathered in department stores to watch the television coverage, while others prayed. Traffic in some areas came to a halt as the news spread from car to car. Schools across the country dismissed their students early. The state funeral took place in Washington, DC during the three days that followed the assassination. Kennedy’s coffin was carried on a horse-drawn caisson to the Capitol to lie in state. Throughout the day and night, hundreds of thousands of people lined up to view the guarded casket. Representatives from over 90 countries attended the state funeral and after the Requiem Mass at St. Matthew’s Cathedral, the late president was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery across the Potomac River from the capital city. His gravesite is now marked by an eternal flame. In a testament to the slain president’s popularity, 50,000 people visited the site each day in the first few years after his death.

President Johnson appointed a special commission to investigate Kennedy’s assassination. Headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren, and therefore known to history as the Warren Commission, they concluded that Oswald was the lone assassin. The ten-month investigation by the Warren Commission concluded that the President was assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald acting alone, and that Jack Ruby acted alone when he killed Oswald before he could stand trial. These conclusions were initially supported by the American public. However, polls conducted from 1966 to 2004 found that as many as 80% of Americans have suspected that there was a plot or cover-up. The assassination is still the subject of widespread debate, and has spawned numerous conspiracy theories.

LYNDON B. JOHNSON

Born in a farmhouse in Stonewall, Texas, the new president had been a high school teacher and worked as a Congressional aide before winning election to the House of Representatives in 1937. He won election to the Senate in 1948 and rose through the ranks of leadership to become the Senate Majority Leader in 1955. Johnson was a master of convincing others to agree with him and he artfully moved legislation through Congress. A contemporary writes of the famous Johnson Treatment, “It was an incredible blend of badgering, cajolery, reminders of past favors, promises of future favors, predictions of gloom if something doesn’t happen. When that man started to work on you, all of a sudden, you just felt that you were standing under a waterfall and the stuff was pouring on you.”

Johnson ran for the Democratic nomination in the 1960 presidential election but lost to Kennedy. He did, however, accept Kennedy’s invitation to be his running mate in the general election.

After Kennedy’s death, Johnson continued both his predecessor’s major political initiatives and maintained his team of advisors. Johnson’s cabinet included several members of Kennedy’s cabinet. Johnson retained Dean Rusk as Secretary of State, Robert McNamara as Secretary of Defense, as well as Kennedy’s Secretaries of Agriculture and the Interior, all for the duration of his presidency. Former presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson continued as Johnson’s Ambassador to the United Nations until Stevenson’s death in 1965. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, the former president’s younger brother, with whom Johnson had a notoriously difficult relationship, remained in office for a few months, before leaving in 1964 to run for the Senate. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

This image captures the infamous Johnson Treatment. The president, on the left, leans in as he makes his case to a reluctant member of congress. Johnson always made sure his chair was higher than those he was meeting with in order to maximize his ability to get the “yes” response he was looking for.

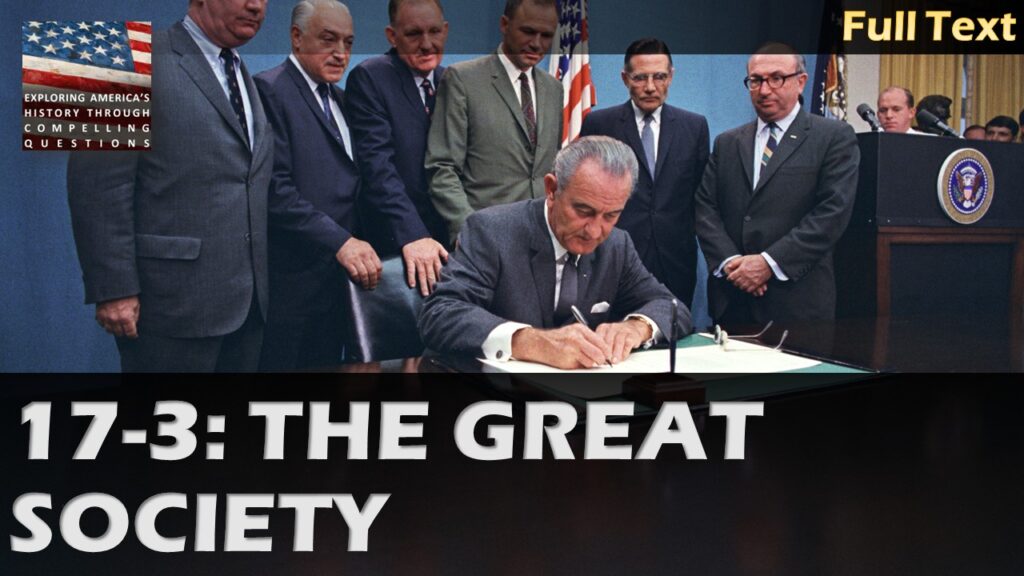

THE GREAT SOCIETY

Johnson continued Kennedy’s push to pass a civil rights law. However, Johnson decided to implement some of his own priorities and a few months after taking office, announced his most famous initiative.

In May 1964, in a speech at the University of Michigan, Lyndon Johnson described in detail his vision of the Great Society he planned to create. Johnson had been a supporter of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal during the 1930s, but those programs were designed to address an economic crisis. In the 1960s, Johnson wanted the nation to go a step further and use all the best of its resources, especially human resources, to become truly great.

Addressing the graduates, he recounted the nation’s past challenges and accomplishments. “For a century we labored to settle and to subdue a continent. For half a century we called upon unbounded invention and untiring industry to create an order of plenty for all of our people.” He proceeded to describe what he saw as the challenge they would have to help him solve in the coming years. “The challenge of the next half century is whether we have the wisdom to use that wealth to enrich and elevate our national life, and to advance the quality of our American civilization. Your imagination, your initiative, and your indignation will determine whether we build a society where progress is the servant of our needs, or a society where old values and new visions are buried under unbridled growth. For in your time we have the opportunity to move not only toward the rich society and the powerful society, but upward to the Great Society. The Great Society rests on abundance and liberty for all.”

For Johnson, “liberty for all” meant freedom from racial injustice, freedom from poverty, as well as the freedom to live in a nation rich with natural beauty, artistic expression, available healthcare, and a government that watched out for the wellbeing of its citizens.

When Congress convened the following January, he and his supporters began their effort to turn his promise into reality. By combatting racial discrimination and attempting to eliminate poverty, the reforms of the Johnson administration changed the nation.

THE WAR ON POVERTY

The centerpiece of Johnson’s plan to create a Great Society was the eradication of poverty in the United States. Johnson had seen poverty up close back in Texas and saw it as a moral issue rather than just a matter of economics. The War on Poverty, as he termed it, was fought on many fronts, but the driving idea behind everything was the help people find ways to rise out of poverty, not just to give them relief. In other words, Johnson wanted the government to use taxpayer money to give the poor a chance, rather than just give them money. As he said it, “I want to be the President who helped to feed the hungry and to prepare them to be taxpayers instead of tax-eaters… I want to be the President who helped the poor to find their own way…”

In the 1960s the economy was doing well and there were jobs available, but for many poor Americans they couldn’t apply for these opportunities because they lacked the skills necessary. The Economic Opportunity Act (EOA) of 1964 established and funded a variety of programs to assist the poor in finding jobs. The Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), first administered by President Kennedy’s brother-in-law Sargent Shriver, coordinated programs such as the Jobs Corps and the Neighborhood Youth Corps, which provided job training programs and work experience for the disadvantaged.

Volunteers in Service to America recruited people to offer educational programs and other community services in poor areas, just as the Peace Corps did abroad. The Community Action Program, also under the OEO, funded local Community Action Agencies, organizations created and managed by residents of disadvantaged communities to improve their own lives and those of their neighbors. The EOA fought rural poverty by providing low-interest loans to those wishing to improve their farms or start businesses. EOA funds were also used to provide housing and education for migrant farm workers. Other legislation created jobs in Appalachia, one of the poorest regions in the United States, and brought programs to Indian reservations. One of EOA’s successes was the Rough Rock Demonstration School on the Navajo Reservation that, while respecting Navajo traditions and culture, also trained people for careers and jobs outside the reservation.

EDUCATION

Johnson, a former teacher, realized that a lack of education was the primary cause of poverty and other social problems. Educational reform was thus an important pillar of the society he hoped to build, and one of the chief pieces of legislation that Congress passed in 1965 was the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). This law provided increased federal funding to both elementary and secondary schools, allocating more than $1 billion for the purchase of books and library materials, and the creation of educational programs for disadvantaged children.

The ESEA was not important only because it provided funding for schools, but also because it was the first time the federal government became involved in providing money for the public schools. For most of the nation’s history, schools were the responsibility of local governments. However, after Johnson’s Great Society, every president and members of congress have promised to improve education and have allocated federal money to do so. Even still, federal funding accounts for only a small fraction of a school’s overall budget. Most of a school’s budget is still provided by local taxes and decisions about curriculum are made at the state and local level. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Lady Bird Johnson reads to students at a Head Start program. She was a champion of all of her husband’s Great Society programs, especially Head Start and his environmental initiatives.

The Higher Education Act, signed into law in 1966, provided scholarships and low-interest loans for the poor, increased federal funding for colleges and universities, and created a corps of teachers to serve schools in impoverished areas. Today, approximately two-thirds of all student financial support comes from the federal government.

When high school seniors complete their Federal Application for Student Aid (FAFSA), they become eligible for any of three forms of federal funding: Grants, or money given, loans, which have to be repaid after graduation, or work-study, which is money that can be earned by working at a job during school.

The planners of education reform that was part of the War on Poverty understood that systemic poverty was generational. That is, being the child of poor parents makes it much more likely that at person will grow up to be poor. One factor in this pattern is the ability to prepare children for kindergarten. While middle and upper class parents can provide books and toys for their young children, take them to museums, zoos, camps or send them to a preschool, poorer parents cannot afford these things, and often gave less time to teach their children because they were working.

To combat this problem, Johnson created Head Start, a program that provided government-funded preschool for low-income families. In this way, children from poor families would not start kindergarten already behind their middle and upper class peers. In 2009, David Deming evaluated the program, using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. He compared siblings and found that those who attended Head Start showed stronger academic performance as shown on test scores for years afterward, were less likely to be diagnosed as learning-disabled, less likely to commit crime, more likely to graduate from high school and attend college, and less likely to suffer from poor health as an adult.

MEDICARE AND MEDICAID

During the New Deal, President Franklin Roosevelt had enacted Social Security, an important program that provides financial support for America’s elderly. Johnson realized that despite Social Security, the nation’s elderly were among its poorest and most disadvantaged citizens, and added to the social safety net by enacting a program to provide medical insurance for the elderly. The creation of Medicare, a program to pay the medical expenses of those over sixty-five, has, along with Social Security, been one of the most popular and most expensive programs run by the federal government. Initially opposed by the American Medical Association, which feared the creation of a national healthcare system, the new program was supported by most citizens because it would benefit all social classes, not just the poor.

Like Social Security, current workers pay the costs of Medicare. As the Baby Boomers retire, more and more will be taking advantage of Medicare benefits and the government will have to pay for their prescription drugs, doctors’ visits, and other treatments. With better healthcare, Americans are living longer. The combined effect of the large number of Baby Boomers and the longer they are all living, the cost of Medicare is rising quickly. Politicians in the coming decades will have to face tough choices. Either they will have to raise taxes on current workers to pay for Medicare’s costs, or cut benefits. Since older Americans vote in greater numbers than younger Americans, the outcome seems obvious.

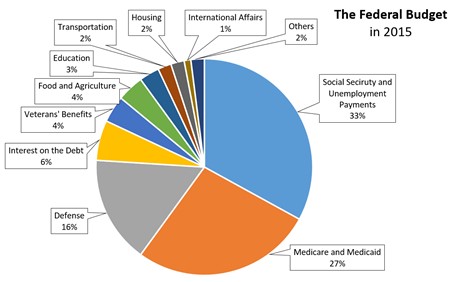

A year after Medicare was created, a medical program for the poor was enacted entitled Medicaid. States use money from the federal government and run the program themselves so Medicaid is known by different names in different places. For example, California calls their program Medi-Cal, in Massachusetts it is known as MassHealth, and Hawaii’s version of Medicaid is called Quest. As part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), also known as Obama Care, passed in 2010, the Medicaid program was greatly expanded by redefining who qualified to receive its benefits. Secondary Source: Chart

Secondary Source: Chart

A pie chart of the federal budget in 2015 shows the enormous expense of the entitlement safety net programs such as Social Security, unemployment, Medicare and Medicaid, which together account for well over half of all federal spending. As the Baby Boomers live out their long retirements, greater and greater allocations will be needed to support these programs. Either taxes on younger workers will have to go up, or the benefits the elderly receive will have to go down.

THE ARTS

Perhaps influenced by Kennedy’s commitment to the arts, Johnson also signed legislation creating the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funding for artists and scholars. In September 1965, when he signed the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities Act, Johnson, declared, “the arts and humanities belong to all the people of the United States.” Government support for the arts is an assertion that culture is a concern of everyone, not just private citizens.

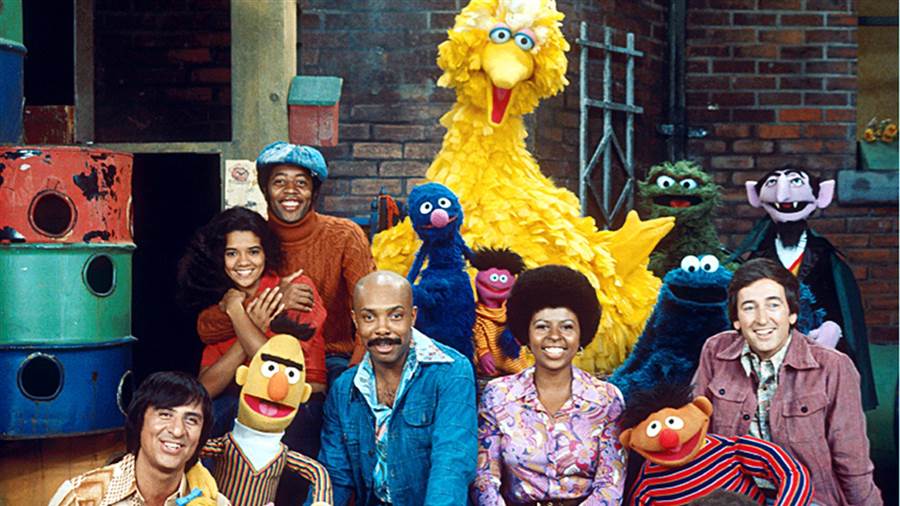

The Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 authorized the creation of the private, not-for-profit Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which helped launch the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) and National Public Radio (NPR) in 1970.

Since its inception, the National Endowment for the Arts and National Endowment for the Humanities have funded theatrical productions, translations of works of literature, art exhibits, and have made the arts accessible to millions of schoolchildren. Sometimes, people forget that the arts are expansive. However, consider the cost of paying for school busses to transport elementary school students to a theater to watch a play. This is an experience most Americans are familiar with, but do not often realize that the cost of those busses was probably paid for with a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Another important project these Great Society programs have undertaken is the recognition of America’s great artists. The National Medal of Arts, given annually by the president has been awarded to such great contributors as painters Georgia O’Keeffe, Jacob Lawrence, and Andrew Wyeth, musicians Dave Brubeck, Wynton Marsalis, Johnny Cash, and Ray Charles, writers Ralph Ellison, and Beverly Cleary, and dancers Mikhail Baryshnikov and Suzanne Farrell. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Sesame Street premiered in 1969, launched with funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

CONSUMER PROTECTION

In the first decade of the 1900s, muckrakers such as Upton Sinclair made food safety a part of the national conversation with their books. The Jungle, for example, helped spur congress to create the Food and Drug Administration. As part of the Great Society, Johnson moved consumer protection a step further.

The Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act of 1965 required packages to carry warning labels. The Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966 set standards through creation of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The Fair Packaging and Labeling Act requires products have a label to identify manufacturer, address, and clearly mark quantity and servings. The Child Safety Act of 1966 prohibited any chemical so dangerous that no warning can make it safe and the Flammable Fabrics Act of 1967 set standards for children’s sleepwear. The Wholesome Meat Act of 1967 and Wholesome Poultry Products Act of 1968 improved inspection of the nation’s meats. The Truth-in-Lending Act of 1968 required lenders and credit providers to disclose the full cost of finance charges in both dollars and annual percentage rates, on installment loan and sales. The Land Sales Disclosure Act of 1968 provided safeguards against fraudulent practices in the sale of land. The Radiation Safety Act of 1968 provided standards and recalls for defective electronic products.

We have Johnson to thank for the fact that we can look on the side of a package at the grocery store and know what ingredients it contains, or eat a hamburger without fearing for our health, or ride in a car and know it will protect us in an accident, or rest easy knowing that the things in our house will not poison our children.

IMMIGRATION

The United States is a nation of immigrants. However, after World War I, people began to fear the impact that immigrants were having. Communists led by Vladimir Lenin had just taken power in Russia, revolutions were brewing in Europe, and traditional racist fears were brewing. In response, Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924, which almost ended legal immigration. It set quotes for how many people could enter the United States from any particular country, favored White Europeans, and ended immigration from Asia all together.

In 1965, the Johnson Administration encouraged Congress to pass the Immigration and Nationality Act, which radically changed the nation’s immigration policy. The law lifted restrictions on immigration from Asia and gave preference to immigrants with family ties in the United States and immigrants with desirable skills. Although the measure seemed less significant than many of the other legislative victories of the Johnson administration at the time, it opened the door for a new era in immigration. When it was first passed, its advocates believed that the trend of predominantly White immigration would continue, since most Americans at the time were White. However, because it favored families, once one immigrant had moved to the United States, the law made it possible for other family members to obtain visas to immigrate as well. Over the past 50 years, this has made possible the formation of Asian and Latin American immigrant communities.

Between the passage of immigration restrictions in the 1920s and the Great Society in the 1960s, 52% of immigrants were from Europe and only 6% were from Asia. Since the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act in 1965, 14% have been from Europe and 33% from Asia. The rebirth of Chinatowns, as well as the establishment of Vietnamese, Thai, Korean, Japanese, Indian, Pakistani, as well as various African ethnic communities in the United States are the effects of the policy change implemented by Johnson.

Immigration from Latin America was not ended in 1924 because of the need for farm workers and Hispanic immigrants have accounted for about 45% of the nation’s total new arrivals in the past 100 years.

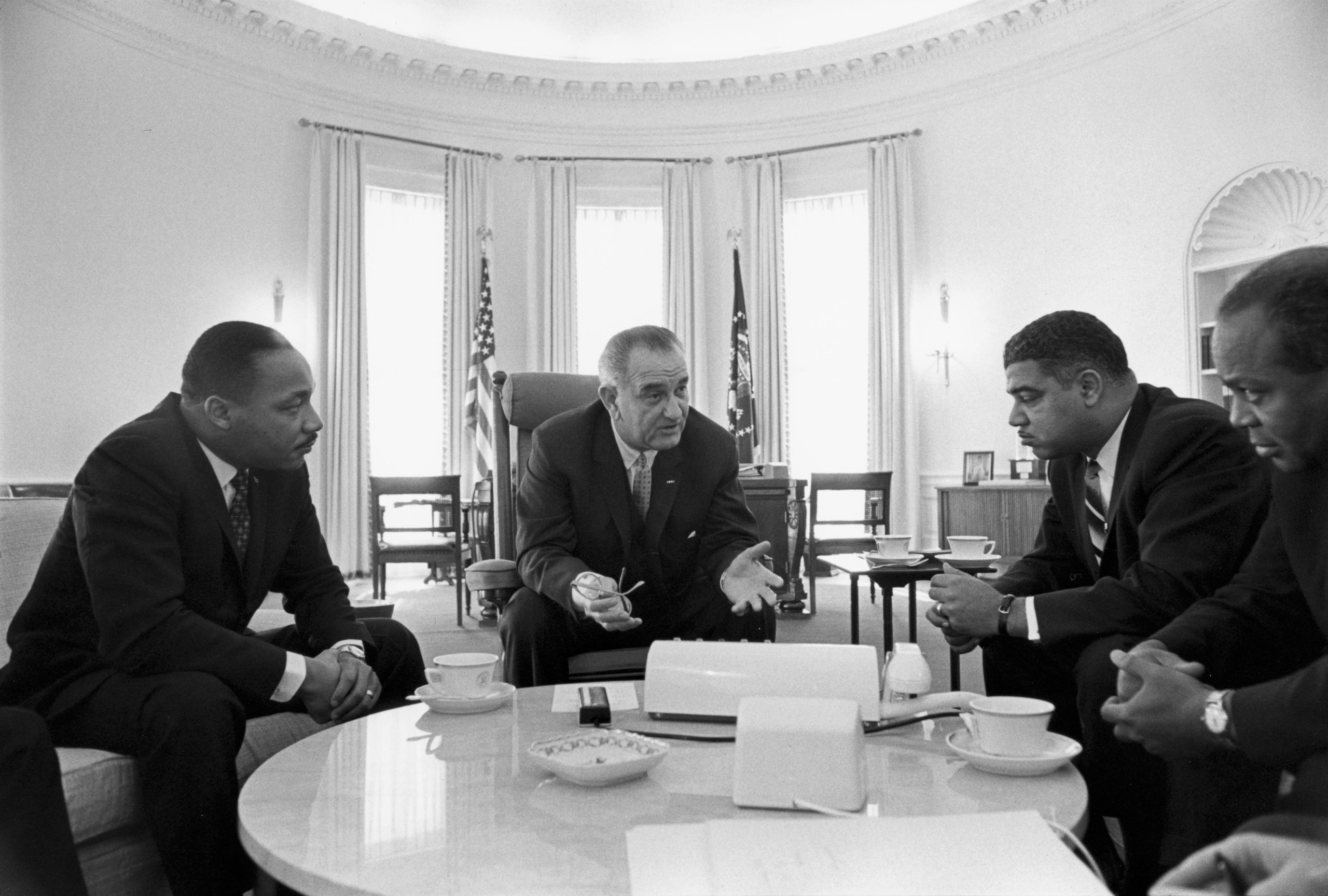

CIVIL RIGHTS AND THE ENVIRONMENT

The fight for civil rights was an important part of Johnson’s quest to create a Great Society. He used his considerable ability to work with Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, both of which we discussed in the preceding unit.

Johnson was also greatly concerned with protecting the environment, which we will discuss at length in our next reading. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

President Johnson met with Martin Luther King, Jr. and other civil rights leaders in the Oval Office of the White House. His support was an important component of the effort to convince Congress to pass both the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

THE END OF THE GREAT SOCIETY

Perhaps the greatest casualty of the nation’s war in Vietnam during the 1960s and early 1970s was the Great Society. As the war escalated, money spent to fund it also increased, leaving less to pay for the many social programs Johnson had created to lift Americans out of poverty. Johnson knew he could not achieve his Great Society while spending money to wage the war, however he was unwilling to withdraw from Vietnam for fear that the world would perceive this action as evidence of American failure. On balance, he was willing to sacrifice all he could do to end poverty and improve life at home so that the United States could carry out its responsibilities as a superpower in the Cold War.

Vietnam doomed the Great Society in other ways as well. Dreams of racial harmony suffered, as many African Americans, angered by the failure of Johnson’s programs to alleviate severe poverty in the inner cities, rioted in frustration. Their anger was heightened by the fact that a disproportionate number of African Americans were fighting and dying in Vietnam. Nearly two-thirds of eligible African Americans were drafted, whereas draft deferments for college, exemptions for skilled workers in the military industrial complex, and officer training programs allowed White middle-class youth to either avoid the draft or volunteer for a military branch of their choice. As a result, less than one-third of White men were drafted.

Although the Great Society failed to eliminate suffering or increase civil rights to the extent that Johnson wished, it made a significant difference in people’s lives. By the end of Johnson’s Administration, the percentage of people living below the poverty line had been cut nearly in half. While more minorities continued to live in poverty, the percentage of poor African Americans had decreased dramatically. The creation of Medicare and Medicaid as well as the expansion of Social Security benefits and welfare payments improved the lives of many, while increased federal funding for education enabled more people to attend college than ever before.

Conservative critics argued that, by expanding the responsibilities of the federal government to care for the poor, Johnson had hurt both taxpayers and the poor themselves. Aid to the poor, many maintained, would not only fail to solve the problem of poverty but would also encourage people to become dependent on the government and lose their desire and ability to care for themselves, an argument that many found intuitively compelling but which lacked conclusive evidence. These same critics also accused Johnson of saddling the United States with a large debt as a result of all the money he borrowed in order to fund both the war in Vietnam and the programs of the Great Society.

THE WARREN COURT

Earl Warren was the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court from 1953 to 1969. His time on the court is remembered as an era in which the Court made numerous progressive decisions that advanced civil rights. During his tenure, Warren wrote the Brown v. Board of Education and Hernandez v. Texas decisions. He ruled that witnesses did not have to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee that had become infamous during the Red Scare. In Engel v. Vitale his court ruled that schools cannot force students to participate in prayers. He was chief justice when President Nixon tried to prevent newspapers from printing stories that contained secrets about the Vietnam War and ruled that the people have the right to know what their government is doing. However, two rulings in particular made by the Warren Court are remembered because together they greatly advanced protection of people accused of crimes, especially for those who are poor.

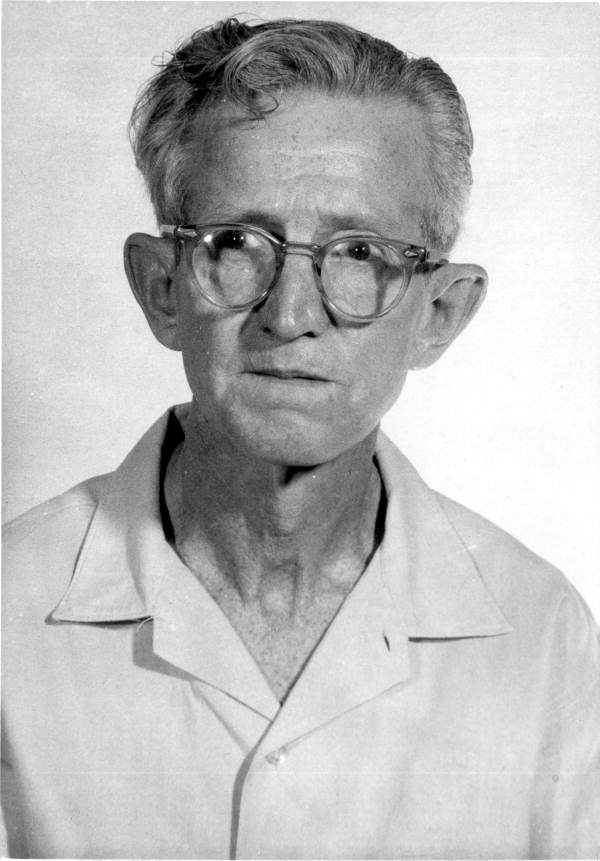

In 1961, a poor man named Clarence Earl Gideon was arrested and put on trial for robbing a pool hall in Florida. When he appeared before the court, Gideon could not afford an attorney to represent him, and the prosecutor easily convinced the jury that Gideon was guilty. However, Gideon was not guilty and believed that he should have been entitled to a government appointed lawyer. Public defenders, as they are known, are lawyers paid with tax money who defend people accused of crimes who cannot afford to hire lawyers of their own. Gideon took his case, Gideon v. Wainwright, all the way to the Supreme Court where he won. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Clarence Earl Gideon was convicted of a crime although he was too poor to afford a lawyer to help with his defense in court. He took his case to the Supreme Court where he won. Today, everyone accused of a crime has the right to an attorney. Those who cannot afford their own lawyer will be represented by a public defender paid for with tax money.

In 1963, Ernesto Miranda was arrested, by the Phoenix Police Department, based on circumstantial evidence linking him to the kidnapping and rape of an eighteen-year-old woman. After two hours of interrogation by police officers, Miranda signed a written confession. However, at no time was Miranda told of his right to consult with a lawyer. Before being presented with the form on which he was asked to write out the confession he had already given orally, he was not advised of his right to remain silent, nor was he informed that his statements during the interrogation would be used against him. These rights are guaranteed by the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution. At trial, when prosecutors offered Miranda’s written confession as evidence, his court-appointed lawyer objected that the confession was not truly voluntary and should be excluded from the trail. Moore’s objection was overruled and Miranda was convicted. Like Gideon, Miranda and Moore believed the police and prosecutors should not be able to use a confession unless the person on trial knew that confession might be used in court. The Supreme Court agreed. In Miranda v. Arizona, they clarified that statements made by those in police custody can only be used in a trial if the person has clearly been warned that such is the case.

This warning is now known as the Miranda Warning, and incorporates both the Gideon case and the Miranda case. The exact wording varies, but could read, “You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can be used against you in court. You have the right to talk to a lawyer for advice before we ask you any questions. You have the right to have a lawyer with you during questioning. If you cannot afford a lawyer, one will be appointed for you before any questioning if you wish. If you decide to answer questions now without a lawyer present, you have the right to stop answering at any time.”

While most Americans eventually agreed that the Court’s desegregation decisions were fair and right, disagreement about the “due process revolution” continues. Warren took the lead in criminal justice despite his years as a tough prosecutor. He always insisted that the police must play fair or the accused should go free. Warren was privately outraged at what he considered police abuses that ranged from warrantless searches to forced confessions.

Conservatives angrily denounced the Warren Court’s decisions claiming that they prevented the police from effectively putting criminals behind bars. Violent crime and homicide rates shot up nationwide in the following years. In New York City, for example, after steady to declining trends until the early 1960s, the homicide rate doubled in the period from 1964 to 1974. Controversy exists about the cause, with conservatives blaming the Supreme Court’s decisions, and liberals pointing to increased urbanization and income inequality characteristic of that era. After 1992 the homicide rates fell sharply.

CONCLUSION

Many liberals would argue that the failure of the War on Poverty to actually end poverty was the fault of external factors such as the Vietnam War. The programs and ideas President Johnson championed would have worked if other distractions had not interfered.

Conservatives, on the other hand, claim that the War on Poverty, while well-intentioned, would never had undone the natural order of the capitalist economic system, and in some ways might have made poverty worse. People who know the government will rescue them when they fall on hard times are less likely to work their way out of poverty. Or so the argument goes.

What do you think? Can we end poverty?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The federal government joined in the efforts to remake American society in the 1960s. President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs were meant to end poverty, protect healthcare and protect the environment. The Supreme Court handed down important rulings about civil rights and criminal justice and the immigration system was significantly changed.

In 1963, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald while riding through Dallas, Texas in an open limousine. A man seeking to avenge the president’s death killed Oswald a few days later. The Warren Commission investigated the killing and found that Oswald had acted alone, but Kennedy’s death remains the subject of conspiracy theories.

The new president was Lyndon Johnson from Texas. Johnson was a long-time member of Congress and a master at convincing others to agree with him.

Johnson continued many of Kennedy’s programs. He also wanted to improve the nation and believed America should be a Great Society.

Johnson declared a War on Poverty. He signed many laws that were designed to end poverty, mostly by giving people the education or support they needed to find jobs, rather than just by giving away money.

Johnson signed the ESEA, which provided federal funding for education. This was the first time the federal government got involved in funding local schools. He also created Head Start for low-income preschoolers and increased federal scholarships and loans for college.

Johnson created Medicare to cover health insurance for the elderly and Medicaid to provide health insurance for the poor. Both programs remain popular and account for about a quarter of the entire federal budget.

Johnson’s Great Society included federal funding for the arts, including funding for public radio and television.

Johnson also passed laws to protect consumers, such as regulations on automobile safety, truth in packaging, and financial disclosures.

Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act, which ended national quotas for immigration and implemented a family reunification policy. This greatly increased immigration from Asia and Africa.

The Great Society and Johnson’s War on Poverty were limited because Johnson was also spending money to fight the Vietnam War. Conservatives criticize the Great Society programs as excessive government.

During the 1960s, the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren ruled on multiple cases that expanded civil rights, including Brown v. Board of Education, as well as cases that led to the creation of the Miranda Warning.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Lee Harvey Oswald: The man who shot and killed President John F. Kennedy. He was killed by Jack Ruby a few days later.

Warren Commission: Group who led the official government investigation of the assassination of President Kennedy. They concluded that Oswald had acted alone.

Earl Warren: Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in the 1950s and 1960s who pushed the Court to rule favorably on numerous cases related to civil rights.

The Warren Court: Nickname for the Supreme Court during the 1950s and 1960s during a period of time when handed down many civil rights and criminal justices rulings that historians view as particularly liberal.

Public Defender: Lawyer paid by tax dollars who defends people who cannot afford a lawyer of their own.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Miranda Warning: Statement made by arresting police officers advising people of their right to remain silent and their right to an attorney.

![]()

GOVERNMENT PROGRAMS & AGENCIES

The Great Society: Collection of laws and problems implemented by President Lyndon Johnson to improve life in America. They included his War on Poverty as well as programs to protect the environment and Medicare and Medicaid.

War on Poverty: Name given to the laws promoted by President Lyndon Johnson designed specifically to help the poor. These included the Jobs Corps which provided training, as well as education laws such as Head Start and college financial aide.

Jobs Corps: Program that was part of Johnson’s War on Poverty. It provides training so people can learn skills they will need to be hired.

Head Start: Preschool program for children from low-income families that was instituted as part of the War on Poverty in the 1960s.

Medicare: Program that provides health insurance for the elderly. It is a signature program created as part of the Great Society in the 1960s by President Johnson.

Medicaid: Program that provides health insurance for lower-income Americans. It is run independently by states and goes by different names in the different states.

National Endowment for the Arts: Program created in the 1960s as part of the Great Society that uses federal tax dollars to fund art exhibits, performances, and art education.

Corporation for Public Broadcasting: Program created in the 1960s as part of the Great Society that uses federal tax dollars to support public television and public radio programing.

![]()

COURT CASES

Gideon v. Wainwright: 1963 Supreme Court cases that guaranteed a lawyer to all those accused of a crime.

Miranda v. Arizona: 1966 Supreme Court case which banned the use of confessions or statements made by a defendant before they had been advised of their right to remain silent. This case led to the now-famous Miranda Warnings.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Dealey Plaza: The location in Dallas, Texas where President Kennedy was assassinated.

![]()

EVENTS

Assassination of John F. Kennedy: November 22, 1963 – Dallas, Texas.

![]()

LAWS & RESOLUTIONS

Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA): Law passed in 1965 as part of the Great Society and War on Poverty that greatly increased federal funding for school and made the federal government a major player in funding education.

Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965: Major revision to immigration law passed in 1965 that eliminated national quotas and instead encouraged family reunification. It led to a tremendous increase in immigration from Asia, Latin America and Africa.