JUMP TO

INTRODUCTION

An atmosphere of fear hung over America during the early years of the Cold War. People feared that communists might achieve their goal of world domination. When the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb in 1949, Americans feared nuclear holocaust. That same year, China, the world’s most populous nation, became communist. Half of Europe was under Josef Stalin’s influence, and every time Americans read their newspapers there seemed to be a new and more terrifying danger.

These fears changed the way Americans thought about freedom and security. Sometimes they became paranoid and ignored basic freedoms as they tumbled over themselves to find communists hidden in their midst. Other times, a desire to defend themselves and stay ahead of the looming danger from the East led to impressive advances in science and engineering.

While the face-to-face standoff between the American armed forces and communist troops might have been far away in Berlin, Korea or Vietnam, the Cold War, like all wars, changed America. Some wars lead to positive outcomes on the home front. For example, the Second World War led to increased participation by women in the workforce, an increased number of Americans going to college due to the GI Bill, and courageous leaders who advanced civil right for African-Americans.

Was this true of the Cold War? Did this long period living on the edge of annihilation make life at home better, or did the Cold War hurt America?

MCCARTHYISM

“Are you, or have you ever been, a communist?” In the late 1940s and early 1950s, thousands of Americans who toiled in the government, served in the army, worked in the movie industry, or came from any number of other walks of life had to answer that question under oath.

It did not take long for the Cold War confrontation in Europe and Asia to come home. In 1947, President Truman had ordered background checks of every civilian in service to the government to make sure they were not secretly supporting communism or Nazism. When Alger Hiss, a high-ranking diplomat at the State Department who had advised Roosevelt at Yalta and been involved in the creation of the United Nations was denounced as a communist and arrested on charges of espionage, Americans panicked. The Hiss trial concluded in 1950 with a conviction. Hiss went to jail, but evidence of his guilt is still inconclusive.

In 1951, husband and wife Julius and Ethel Rosenburg were accused of passing nuclear secrets to the Soviet Union. Like Alger Hiss, the Rosenbergs maintained their innocence. While the evidence against Julius was convincing, Ethel’s involvement in the plot seems to have been less crucial. All the same, they were both convicted and put to death in the electric chair.

Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin capitalized on national paranoia by proclaiming that communists were omnipresent and that he was America’s only salvation. Historians often label his efforts a witch hunt in reference to the Salem Witch Trials of the 1600s in which dozens of people were falsely accused.

At a speech in Wheeling, West Virginia, on February 9, 1950, McCarthy launched his first salvo. He proclaimed that he was aware of 205 card-carrying members of the Communist Party who worked for the State Department. A few days later, he repeated the charges at a speech in Salt Lake City. McCarthy began to attract headlines, and the Senate asked him to make his case. As it turned out, McCarthy was never able to provide any evidence to support his sensational accusations.

On February 20, 1950, McCarthy addressed the Senate and made a list of dubious claims against suspected communists. He originally cited 81 cases that day but skipped several as he went, and for most cases repeated the same flimsy information. He proved nothing that day, but the Senators were suspicious enough that they called for a full investigation. McCarthy was in the national spotlight.

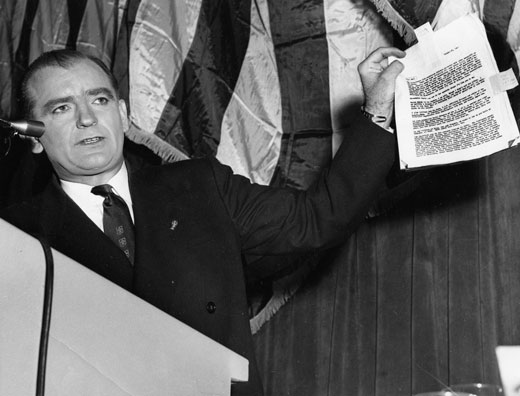

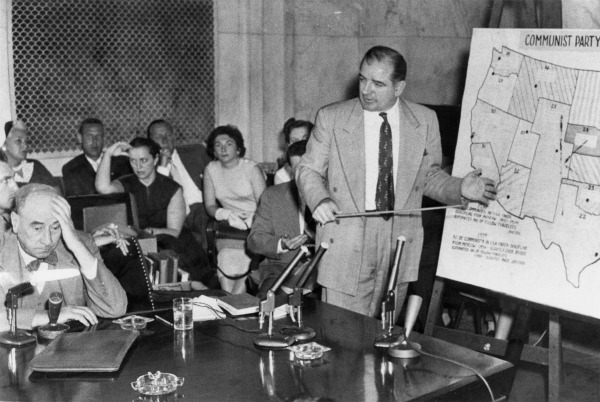

Staying in the headlines was a full-time job. After accusing low-level officials, McCarthy went for the big guns, even questioning the loyalty of Dean Acheson and George Marshall, two of the most respected republican leaders of the day. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Senator Joseph McCarthy claiming to know of communists working in the State Department.

Some Republicans in the Senate were aghast and disavowed McCarthy. Others such as Senator Robert Taft and Congressman Richard Nixon saw him as an asset. The public loved the show. It was emotionally rewarding to think that someone was making sure the country was safe from communist infiltration, and McCarthy was a master of alternately stoking fear and then providing a show of strength and resolve. His supporters rewarded the witch-hunters by sending red-baiters to Washington to file accusations against suspected Reds, providing plenty of work for McCarthy and his fellow communist hunters.

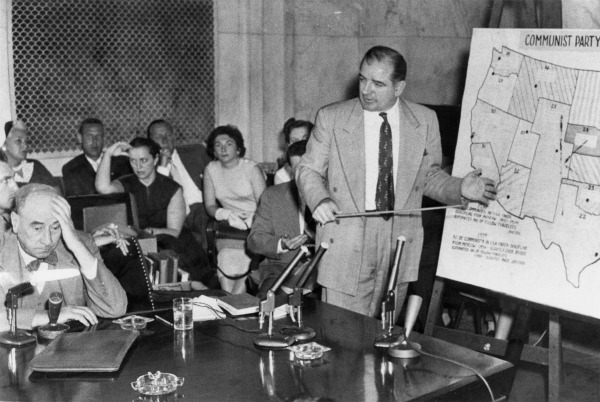

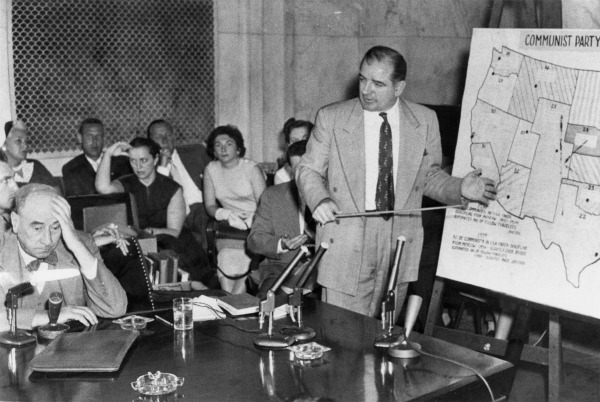

Dwight Eisenhower, the hero of World War II had no love for McCarthy. Eisenhower could see through McCarthy’s charade, but when Eisenhower was elected president in 1952, he was reluctant to condemn McCarthy for fear of splitting the Republican Party. McCarthy’s accusations went on into 1954, when the Wisconsin senator turned his sights on the United States Army. For eight weeks, in televised hearings, McCarthy interrogated army officials, including many decorated war heroes. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Senator Joseph McCarthy and Welch at the Army hearings.

This was his tragic mistake. Television was new in the 1950s, and for the first time Americans were able to watch McCarthy live. Instead of showing a noble crusader, television illustrated the mean-spiritedness of McCarthy’s campaign. The army then went on the attack, questioning McCarthy’s methods and credibility leading up to one of the most memorable lines in government history. Joseph Welch, a lawyer for the army challenged McCarthy, “Until this moment, Senator, I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness.” Then, defending the young man McCarthy was accusing, Welch went on, “Let us not assassinate this lad further, senator. You have done enough. Have you no sense of decency?”

Americans agreed. McCarthy was a jerk, and Welch and television proved it. The American people thought McCarthy unscrupulous in his attacks. Poll after poll showed that Americans would not tolerate attacks on the brave men and women in the armed forces.

Fed up with the embarrassing show, McCarthy’s colleagues censured him for dishonoring the Senate, and the hearings came to a close. Plagued with poor health and alcoholism, McCarthy himself died three years later.

HUAC

Senator McCarthy was not the only individual to make a name for himself seeking out potential communists. Members of the House of Representatives wanted to show that they were just as enthusiastic about rooting out the red threat.

The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) targeted the Hollywood film industry. Actors, writers and producers alike were summoned to appear before the committee and provide names of colleagues who may have been members of the Communist Party.

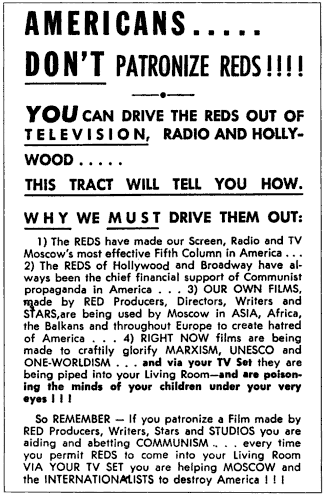

Those who repented and named names of suspected communists were allowed to return to business as usual. Those who refused to address the committee were cited for contempt. Since the First Amendment protects Americans’ right to free speech and freedom of assembly, there is nothing illegal about being communist, meeting with communists, or spreading communist ideas. Primary Source: Document

Primary Source: Document

A warning to Americas during the height of the Red Scare focused especially on the supposed influence of communists in Hollywood.

When ten writers and directors refused to answer the questions the HUAC members posed, citing their first amendment rights, they were cited for contempt of Congress. This was a dubious charge legally since Congress does not have the right to question anyone’s political beliefs, but in the hysteria of the early 1950s, even being accused of being a communist was tantamount to a social death sentence.

The Hollywood 10 as they came to be called were fined, jailed, and lost their jobs. Like others who were accused of being communist during this time, they were blacklisted, meaning that no one would hire them. Years passed before they had their reputations restored.

Americans had mixed feelings about the Hollywood 10. Some people admired them for standing up to government officials who were abusing the Constitution. Others felt that communism was such an existential threat that bending the rules was necessary to protect the nation.

EFFECTS OF THE RED SCARE

This era in American history is called the Red Scare or McCarthyism and we look back with some mystification. How could people have been so consumed by fear that they ignored the Constitution? Were there in fact communists in America? The answer is undoubtedly yes, but many of the accused had attended communist events many years before the hearings. In fact, it had been fashionable to do so in the 1930s.

Although Soviet spies did penetrate the highest levels of the American government, the vast majority of the accused were innocent victims. All across America, state legislatures and school boards mimicked McCarthy and HUAC. Thousands of people lost their jobs and had their reputations tarnished.

Unions were a special target of communist hunters. Sensing an unfavorable environment, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) merged in 1955 to close ranks. Librarians and school boards pulled books from library shelves that they thought might corrupt the minds of children, including Robin Hood, which was deemed dangerous for spreading the communist-like notion of stealing from the rich to give to the poor.

Some famous politicians first got their start during the Red Scare. Unlike Senator McCarthy who fell into disgrace, congressman Richard Nixon polished his anti-communist credentials as a member of HUAC and was selected by Eisenhower to be vice president. Later, Nixon capitalized on his tough reputation when he ran for president himself. Another future president, an actor name Ronald Reagan was elected president of the Screen Actors Guild, the union of Hollywood actors, and worked to root out communists from within the ranks of the Hollywood elite.

The Red Scare cast a long shadow over American foreign policy as well. For more nearly two decades, no politician could consider visiting or opening trade with China or withdrawing troops from Southeast Asia without being branded a communist. Ultimately, it was Richard Nixon, one of the great heroes of HUAC, who was able to visit China without being suspected of being soft on communists.

Above all, several messages became crystal clear to the average American: Don’t criticize the United States and don’t be different.

ATOMS FOR PEACE

As the arms race intensified, fear among the general public about the mysterious dangers of atomic weapons intensified. Research on atomic energy was a strictly held secret and the results of that research had been used only for developing weaponry. President Eisenhower wanted to change that, and on December 8, 1953, he delivered a groundbreaking speech to the United Nations General Assembly that has become known as “Atoms for Peace.”

Eisenhower was determined to solve “the fearful atomic dilemma” by finding some way by which “the miraculous inventiveness of man would not be dedicated to his death, but consecrated to his life.” Essentially, Eisenhower argued, the nations of the world should share the discoveries they were making in the field of atomic energy so that the technologies that were being developed for war could also be applied to civilian purposes – electricity production and medicine for example.

Atoms for Peace opened up nuclear research to civilians and countries that had not previously possessed nuclear technology. This made it possible for some countries to develop weapons. However, the Atoms for Peace program that Eisenhower’s speech initiated had great impacts on the world.

Atoms for Peace created the ideological background for the creation of the International Atomic Energy Agency and the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. Eisenhower argued for a nonproliferation agreement throughout the world and argued for a stop of the spread of military use of nuclear weapons. Although the nations that already had atomic weapons kept their weapons and grew their supplies, very few other countries have developed similar weapons since. In this way, Eisenhower was successful.

The Atoms for Peace program also created regulations for the use and handling of nuclear material and production of nuclear power. Today, there are over 440 nuclear reactors in 31 countries that provide about 11% of the world’s electricity. In the United States, 99 reactors provide about 19% of our electricity. Atomic technologies have been used by doctors to diagnose illnesses and treat cancers, in agriculture to eradicate pests, and in industry to develop smoke detectors and perhaps eventually, automobiles. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

The Grafenrheinfeld Nuclear Power Plant in Germany. The steam rising from the cooling towers is non-polluting. The use of nuclear technology for civilian purposes was an important product of Eisenhower’s Atoms for Peace program.

The Atoms for Peace speech and program helped Americans and the people of the rest of the world see the benefits and not just the terror of nuclear power. However, Atoms for Peace did nothing to slow the arms race. The belief that in order to avoid a nuclear war the United States must stay on the offensive, ready to strike at any time, meant that the arms race was essential to preserve our very existence, and the same belief is the reason that the Soviet Union would not give up its atomic weapons either. In fact, during Eisenhower’s time in office, the nuclear holdings of the United States rose from 1,005 to 20,000 weapons.

THE MILITARY INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX

Before World War II, the United States didn’t have a permanent military industry. In times of war, companies that built cars, refrigerators, and all the other things that were sold to consumers simply adapted their factories to produce tanks, bombers and bombs. This was the basis for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s famous Arsenal of Democracy.

However, the realities of the Cold War were different. The nuclear standoff with the Soviet Union meant that the United States could never go back to a time when the government was not developing, producing and buying new weapons systems. And so, a complex and enduring network grew up between the military who needed the latest weaponry, the companies who developed and built those weapons, and Congress which provided the funds.

President Eisenhower warned Americans about the danger of this relationship, which he dubbed the Military Industrial Complex. He foresaw a time when members of congress would realize that they needed the votes of workers at major defense contractors such as Lockheed Martin, Boeing, or Raytheon and would make sure that the military purchased new aircraft, missiles, and guns from these hometown producers. In the end, the government would spend tax dollars, not because the military needed a particular new weapon, but because these contracts were important for creating jobs.

Since the 1950s, many leaders have tried to reduce the size of the nation’s arsenal, or stop the purchase of new equipment they deem unnecessary, only to come up against the resistance of the Military Industrial Complex and find that the demands of the Cold War have irreversibly changed the way our country produces the tools of war.

EDUCATION

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the world’s first satellite. Suddenly, there was concrete evidence that Soviet education might be superior to that in the United States, and Congress reacted by passing the National Defense Education Act to bring American schools up to speed.

Since the defense of the nation was based on nuclear weapons, there was a tremendous need for the scientists and mathematicians who could develop these essential technologies. New electronic computers created a demand for programmers. For years, the United States had relied on well-educated refugees from Europe for its top mathematicians, but it was clearly time for the United States to educate its own. Consequently, the law’s focus was preparing young people to excel in math and science.

The law provided funding for schools to upgrade their science laboratories and to train new math and science teachers. It provided loans for students to attend college. It provided money for students to study languages that might help national defense such as Russian. The law initiated a search for talented students, which gave birth to gifted and talented programs in public schools across the country.

Perhaps most importantly in the long term, however, was that the Cold War changed Americans’ attitudes towards science in public schools. In the 1920s, a great debate had raged between believers in modernism and traditionalists who insisted that the Bible be the basis for scientific study. The 1925 Scopes Trial had epitomized this conflict. In the 1950s, all that changed. Studying science, not the Bible, was essential for the nation’s survival. The traditionalists did not disappear, but at least while the Soviet Union’s missiles were aimed at America, science and mathematics ruled the public schools.

THE MISSILE GAP

Another important consequence of the Soviet launch of Sputnik was the growing prevalence of the idea that the United States was falling behind in its total number of missiles. By this time the actual number of nuclear missiles and bombs each nation had was irrelevant since they could destroy one another many times over, but the fear of being somehow behind our rivals was potent.

In the early 1950s, American magazines began carrying stories about nuclear powered or nuclear armed Soviet bombers crossing the Arctic and raining destruction down on the United States. Although they were much exaggerated and proven false by subsequent U-2 spy plane missions over the Soviet Union, stories of a bomber gap put pressure on members of Congress to act. In response, the air force increased its own bomber fleet to a whopping 2,500 aircraft, far exceeding what turned out to be an imagined, rather than real threat.

Fear of a bomber gap was soon replaced, however, by fear of a missile gap. Missiles were far more terrifying than bombers since they could strike with less warning, and covered the distance from their bases deep inside the Soviet Union to their targets in the United States in minutes rather than hours. Incoming bombers might be intercepted and shot down by fighter aircraft, but no one had any way to defend against incoming missiles. Then Senator John F. Kennedy helped popularize this notion in speeches as he geared up for his presidential campaign in 1960.

President Eisenhower, who knew full well that there was no missile gap, was irritated by Kennedy’s rhetoric. He knew that fear was an infection that could lead to problems in society, and despite his efforts to provide reassuring, steady, thoughtful leadership, the public seemed to by buying into the idea. Once again, pressure mounted on congress to allocate funds to increase the arsenal of nuclear-tipped missiles.

Ironically, talk of a missile gap probably made America less safe since Soviet leaders began to view Kennedy as an extremist warmonger. When Kennedy authorized the invasion of communist Cuba in 1961 at the Bay of Pigs their fears were confirmed and Kennedy’s campaign talk of a missile gap, which he had known was an exaggeration, ended up making the Cuban Missile Crisis much more dangerous than it had to be.

Whether they bought into the idea of the bomber gap and missile gap or not, Americans had legitimate fears when it came to nuclear attack. What could a regular citizen do if the Soviets decided to launch a nuclear first strike? In reality, the answer was nothing, but this was entirely un-reassuring. A whole industry grew up during the 1950s to build bomb shelters in backyards and basements. Complete with beds, tins of crackers and barrels of water, these shelters were advertised in popular magazines and in newspapers. While a personal shelter might save a family from the blast and radioactive fallout of a nuclear attack, it is hard to imagine what sort of world they might climb out to find after consuming their rations of stale crackers.

EISENHOWER’S FAREWELL

Shortly after taking the oath of office in 1953, President Eisenhower had delivered a speech in which he warned about the cost of expanding the armed forces. A former general and hero of the Second World War, Eisenhower surprised many with his dovish tone. He said, “Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children. The cost of one modern heavy bomber is this: a modern brick school in more than 30 cities. It is two electric power plants, each serving a town of 60,000 population. It is two fine, fully equipped hospitals. It is some fifty miles of concrete pavement. We pay for a single fighter with a half-million bushels of wheat. We pay for a single destroyer with new homes that could have housed more than 8,000 people… This is not a way of life at all, in any true sense. Under the cloud of threatening war, it is humanity hanging from a cross of iron.” Primary Source: Document

Primary Source: Document

Page 15 from Eisenhower’s copy of his farewell address that he used during the television broadcast

By the time his presidency ended eight years later, Eisenhower had presided over a long period of economic growth and also a huge expansion of the military. A few days before he handed off power to John F. Kennedy, the young president-elect, Eisenhower appeared on television to speak to the nation one last time. In this farewell address, his message was even more urgent. He warned of the danger of the Military Industrial Complex, a term he coined for the speech, and also against the growing influence of government-funded, defense-oriented research, which he saw as limiting the natural curiosity of America’s brightest minds.

He urged leaders in American and the world to act cautiously, to keep an eye on the distant future and avoid rash acts that might seem necessary in the moment but would endanger generations to come.

Years later, we can look back and see the wisdom that the aging president imparted. His lessons about developing understanding, avoiding unnecessary conflict, guarding against undue influence, and seeking ways to disarm apply as much today as they did in 1961.

CONCLUSION

Every war America has fought has had impacts on the home front. People make sacrifices to support the troops or take jobs in new places to fill in for workers who have taken up arms. But no war produced results at home quite like the Cold War. We transformed our economy. We learned to live in perpetual fear. In some cases, we turned on one another. Although President Eisenhower did his best to turn the negatives of nuclear war into positive advances for humanity, so many aspects of fighting the Cold War turned out to be bad for everyday Americans.

Of course, what was the alternative to fighting the communists? Letting them win? That would have been a catastrophe! Certainly, the benefit of saving freedom for humankind outweighs any price we had to pay. What do you think? Did the Cold War hurt America?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: Fear of communism led Americans to turn on one another and changed the relationship between the military, government and defense contractors. However, the Cold War also led to improvements in education and new technologies for civilian use.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, a second Red Scare swept the United States. People in both the House of Representatives and especially Senator Joseph McCarthy investigated suspected communists. Many people’s careers were ruined by false accusations since few real communists were ever found. Those that did, such as spies who had given nuclear secrets to the Soviet Union, fueled fears that gave power to the accusers.

President Eisenhower wanted to find ways to use nuclear power for good, not just for weapons of destruction. His Atoms for Peace program encouraged the sharing of nuclear technology to support things such as medicine and nuclear power stations to generate electricity.

When he left office, Eisenhower warned America about the danger posed by the Cold War’s long period of military readiness. Unlike past wars that ended, the Cold War was always about to begin. This meant that the government was always spending money to have the latest military technology, and the companies and workers that supplied those weapons relied on tax money being spent for their jobs. Eisenhower warned that this would lead to unnecessary spending in the future, which has turned out to be true.

In fact, during the election campaign of 1960, Kennedy encouraged this sort of spending by claiming that the United States had fewer missiles than the Soviet Union. This missile gap did not actually exist, but many people were so afraid of communists that they believed it anyway and their fear encouraged politicians to vote to spend money on the military.

Fear that the communists might be more advanced in the fields of science and math, and therefore might be able to surpass the United States in weapon design, led to spending in education. Science education became important again and many colleges and high schools built new science labs and hired science teachers.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Alger Hiss: American diplomat who had advised Roosevelt at Yalta and was involved in the creation of the United Nations. He was denounced as a communist during the Red Scare. He was convicted but evidence of his guilt is inconclusive.

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg: Julius Rosenberg was scientist who gave nuclear secrets to the Soviet Union. He and his wife Ethel were tried, convicted and put to death during the Red Scare.

Joseph McCarthy: Senator who became famous as an accuser during the Red Scare. He rarely presented evidence and was eventually discredited.

Reds: Derogatory nickname for communists.

Hollywood 10: A group of ten Hollywood writers, producers and directors who were accused of being communist. They refused to answer questions from HUAC and were blacklisted.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Military Industrial Complex: President Eisenhower’s term for the relationship between the military, weapons manufacturers, and lawmakers who allocated funding for weapons systems.

Bomber Gap: A perceived lack of long-range bombers capable of striking the Soviet Union in the early 1950s. There was no gap – the United States had a roughly equal number of bombers as the Soviet Union. Concern, however, meant an increase in spending for bomber aircraft.

Missile Gap: A perceived lack of ICBMs compared to the Soviet Union. There was actually no gap, but the public became concerned with Senator Kennedy repeatedly used the term to stoke fear during his 1960 presidential campaign.

Bomb Shelters: A place that would be safe during an atomic attack. They were often stocked with food, water, and medical supplies.

![]()

SPEECHES

McCarthy’s 205 Communists: McCarthy claimed to know of 205 communists working in the State Department during a speech in 1950. He never provided evidence but his claim and subsequent Senate hearings made him famous.

Have you no sense of decency?: Famous line from Army lawyer Joseph Welch during the Red Scare. His televised question helped discredit Joseph McCarthy.

Atoms for Peace: A speech given by President Eisenhower in 1953 (and the government programs that followed) that encouraged the civilian use of nuclear technology.

Eisenhower’s Farewell Address: Televised address by departing President Eisenhower in 1961 shortly before Kennedy took office. Eisenhower warned of the dangers of all-or-nothing thinking and the growing influence of a military industrial complex.

![]()

GOVERNMENT & INTERNATIONAL AGENCIES

Second Red Scare: The period in the late 1940s and early 1950s when the fear that communists were infiltrating America drove wild accusations and political investigations.

McCarthyism: Another term often used for the Second Red Scare which refers to the unfounded accusations common of the time.

![]()

EVENTS

Second Red Scare: The period in the late 1940s and early 1950s when the fear that communists were infiltrating America drove wild accusations and political investigations.

McCarthyism: Another term often used for the Second Red Scare which refers to the unfounded accusations common of the time.

![]()

LAWS & TREATIES

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty: A treaty signed in 1968 by all but four countries in the world. Nations promise not to acquire nuclear weapons (if they don’t already possess them) and in exchange they may use nuclear technology for civilian purposes.

National Defense Education Act: Law passed in 1957 after the launch of Sputnik. It provided funding for science and mathematics education in schools and universities.