TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

For over 200 years of America’s history, African Americans had been slaves, primarily in the southern states. In the 1860s, slavery ended with the Civil War, but the position of African Americans at the bottom of the social order did not change much, despite the best efforts of reform-minded Reconstructionists. However, in the 1920s a group of African Americans in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City began promoting the idea of the New Negro. For them, things were changing.

What was it that they saw as new? If the former slaves and their children had been the Negro of the later 1800s, what was new about the African Americans in the 1920s?

What did it mean to be a New Negro that was different from the African Americans of the period between the end of slavery and WWI?

AFRICAN AMERICAN LIFE AFTER RECONSTRUCTION

After the Civil War ended in 1865, the victorious Union spent eleven years trying to remake the South. Although three constitutional amendments were passed ending slavery, granting citizenship to former slaves, and legally giving voting rights to all men, the era of Reconstruction is often seen as a failed effort to change the culture of the South. As many historians have said, the North won the war but lost the peace.

After the end of Reconstruction in 1877, with the passage of new constitutions, Southern states adopted provisions that caused disenfranchisement of large portions of their populations by skirting constitutional protections. While their voter registration requirements applied to all citizens, in practice, they disenfranchised most Blacks.

Democratic state legislatures passed Jim Crow laws to assert white supremacy, establish racial segregation in public facilities, and treat Blacks as second-class citizens. The landmark court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 held that “separate but equal” facilities, as on railroad cars, were constitutional. Thus were born segregated public schools.

For the national Democratic Party, the alignment after Reconstruction resulted in a powerful Southern region that was useful for congressional clout. Virginian Woodrow Wilson, one of the two Democrats elected to the presidency between Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt, was the first Southerner elected after 1856. He benefited from the disenfranchisement of Blacks and the crippling of the Republican Party in the South.

THE NIAGARA MOVEMENT

Born into slavery in Virginia in 1856, Booker T. Washington became an influential African American leader in the ear after Reconstruction. In 1881, he became the first principal for the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, better known as the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, a position he held until he died in 1915. Tuskegee was an all-black normal school, an old term for a teachers’ college, teaching African Americans a curriculum geared towards practical skills such as cooking, farming, and housekeeping. Graduates would then travel through the South, teaching new farming and industrial techniques to rural communities. Washington extolled the school’s graduates to focus on the Black community’s self-improvement and prove that they were productive members of society, something Whites had often doubted was possible.

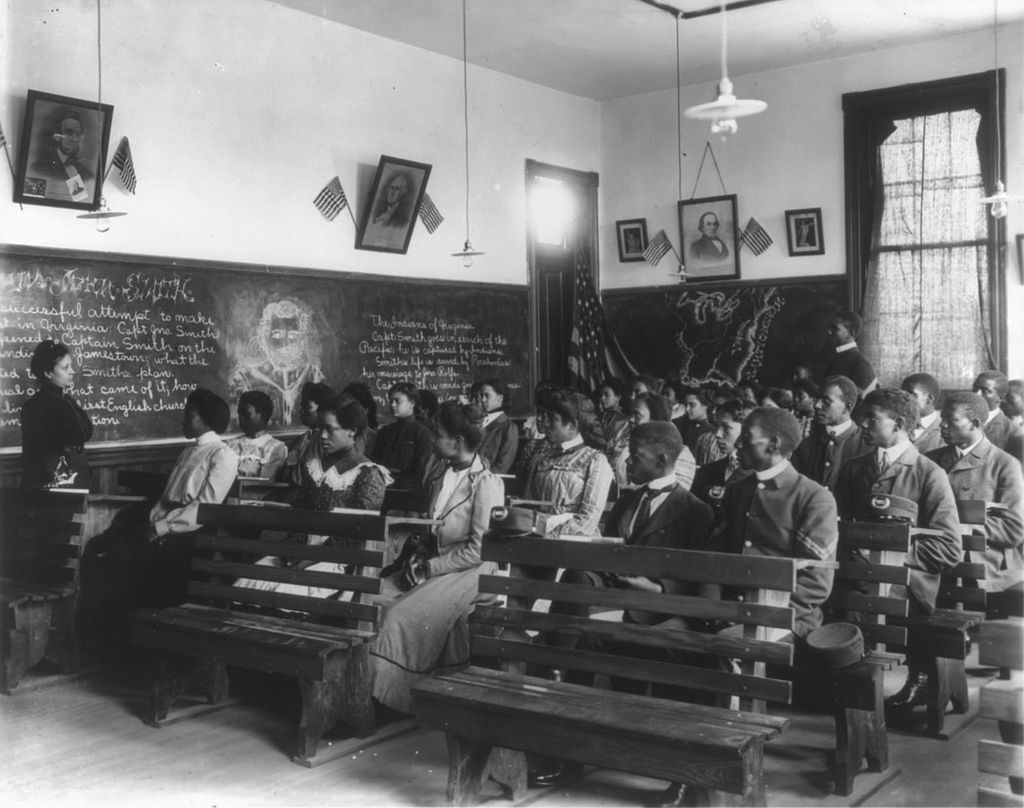

In a speech delivered at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta in 1895, which was meant to promote the economy of the South, Washington proposed what came to be known as the Atlanta Compromise. Speaking to a racially mixed audience, Washington called upon African Americans to work diligently for their own uplift and prosperity rather than preoccupy themselves with political and civil rights. Their success and hard work, he implied, would eventually convince southern Whites to grant these rights. Not surprisingly, most Whites liked Washington’s model of race relations, since it placed the burden of change on Blacks and required nothing of Whites. Wealthy industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller provided funding for many of Washington’s self-help programs, as did Sears, Roebuck & Co. co-founder Julius Rosenwald, and Washington was the first African American invited to the White House by President Roosevelt in 1901. At the same time, his message also appealed to many in the Black community, and some attribute this widespread popularity to his consistent message that social and economic growth, even within a segregated society, would do more for African Americans than agitation for equal rights. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

A history class at the Tuskegee Institute in 1902. Booker T. Washington emphasized education as a means to be productive citizens, but not citizens who would agitate for change to the Jim Crow system of the South.

Yet, many African Americans disagreed with Washington’s approach. Much in the same manner that Alice Paul felt the pace of the struggle for women’s rights was moving too slowly under the NAWSA, some within the African American community felt that immediate agitation for the rights guaranteed under the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, established during the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, was necessary. In 1905, a group of prominent civil rights leaders, led by W. E. B. Du Bois, met in a small hotel on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls, where segregation laws did not bar them from hotel accommodations, to discuss what immediate steps were needed for equal rights. Du Bois, a professor at the all-black Atlanta University and the first African American with a doctorate from Harvard, emerged as the prominent spokesperson for what would later be dubbed the Niagara Movement. By 1905, he had grown wary of Booker T. Washington’s calls for African Americans to accommodate White racism and focus solely on self-improvement. Du Bois, and others alongside him, wished to carve a more direct path towards equality that drew on the political leadership and litigation skills of the black, educated elite, which he termed the talented tenth.

At the meeting, Du Bois led the others in drafting the Declaration of Principles, which called for immediate political, economic, and social equality for African Americans. These rights included universal suffrage, compulsory education, and the elimination of the convict lease system in which tens of thousands of Blacks had endured slavery-like conditions in southern road construction, mines, prisons, and penal farms since the end of Reconstruction. Within a year, Niagara chapters had sprung up in twenty-one states across the country. By 1908, internal fights over the role of women in the fight for African American equal rights lessened the interest in the Niagara Movement. However, the movement laid the groundwork for the creation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909 to fight for African American rights in the courts. Du Bois served as the influential director of publications for the NAACP from its inception until 1933. As the editor of the journal The Crisis, Du Bois had a platform to express his views on a variety of issues facing African Americans in the later Progressive Era, as well as during World War I and its aftermath.

In both Washington and Du Bois, African Americans found leaders to push forward the fight for their place in the new century, each with a very different strategy. Both men cultivated ground for a new generation of African American spokespeople and leaders who would then pave the road to the modern civil rights movement after World War II.

THE GREAT MIGRATION

Between the end of the Civil War and the beginning of the Great Depression in 1929, nearly two million African Americans fled the rural South to seek new opportunities elsewhere. The vast majority of these internal migrants moved to the cities of the industrial North during World War I. New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, St. Louis, Detroit, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Indianapolis were the primary destinations for these African Americans. Together, these eight cities accounted for over two-thirds of the total population of the African Americans who travelled during this Great Migration.

A combination of both push and pull factors played a role in this movement. Despite the end of the Civil War and the passage of constitutional amendments ensuring freedom, the right to vote and equal protection under the law, African Americans were still subjected to intense racial hatred. For African Americans fleeing this culture of violence, Northern and Midwestern cities offered an opportunity to escape the dangers and intense poverty of the South.

In addition to this push out of the South, African Americans were also drawn to the cities of the North by job opportunities which had opened up when White men left for the army during World War I. Although many lacked the funds to move themselves, factory owners and other businesses that sought cheap labor assisted the migration. Often, the men moved first then sent for their families once they were ensconced in their new city life. Racism and a lack of formal education relegated these African American workers to many of the lower-paying unskilled or semi-skilled occupations. More than 80% of African American men worked menial jobs in steel mills, mines, construction, and meatpacking. In the railroad industry, they were usually employed as porters or servants. In other businesses, they worked as janitors, waiters, or cooks. African American women, who faced discrimination due to both their race and gender, found a few job opportunities in the garment industry or laundries, but were more often employed as maids and domestic servants. Regardless of the status of their jobs, however, African Americans earned higher wages in the North than they did for the same occupations in the South and typically found housing to be more available. Secondary Source: Map

Secondary Source: Map

This map shows the concentration of African Americans in the United States in 1900 before the Great Migration. The darker colors show counties in which a higher percentage of residents were African American.

However, such economic gains were offset by the higher cost of living in the North, especially in terms of rent, food costs, and other essentials. As a result, African Americans usually found themselves living in overcrowded, unsanitary conditions, much like the tenement slums in which European immigrants lived in the cities. For newly arrived African Americans, even those who sought out the cities for the opportunities they provided, life in these urban centers was exceedingly difficult. They quickly learned that racial discrimination did not end at the Mason-Dixon Line, but continued to flourish in the North as well as the South. European immigrants, also seeking a better life in the cities of the United States, resented the arrival of the African Americans, whom they feared would compete for the same jobs or offer to work at lower wages. Landlords frequently discriminated against them. Their rapid influx into the cities created severe housing shortages and even more overcrowded tenements. Homeowners in traditionally White neighborhoods later entered into covenants in which they agreed not to sell to African American buyers. Some bankers practiced mortgage discrimination, later known as redlining, in order to deny home loans to qualified buyers who wanted to buy houses in White neighborhoods, indicated on a map with a red line. Such pervasive discrimination led to a concentration of African Americans in some of the worst slum areas of most major metropolitan cities, a problem that persists today.

THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE

Beginning in the early 1900s, the neighborhood of Harlem on the island of Manhattan in New York City became home to a growing African American middle class. In 1910, a large block along 135th Street and Fifth Avenue was purchased by various African-American realtors and a church group. Many more African Americans arrived during World War I. Due to the war, the migration of laborers from Europe virtually ceased, while the war effort resulted in a massive demand for unskilled industrial labor. The Great Migration brought hundreds of thousands of African Americans from the South. Among them were a great number of artists, writers, musicians and thinkers who would live and work together in Harlem. Their ideas and creative talents marked an outpouring of cultural creation and pride called the Harlem Renaissance.

Characterizing the Harlem Renaissance was an overt racial pride that came to be represented in the idea of the New Negro, who through intellect and production of literature, art, and music could challenge the pervading racism and stereotypes to promote progressive or socialist politics, and racial and social integration. The creation of art and literature would serve to uplift the race. Thus, the Harlem Renaissance embraced the ideas of W. E. B. Du Bois and rejected the Atlanta Compromise of Booker T. Washington.

There would be no uniting form singularly characterizing the art that emerged from the Harlem Renaissance. Rather, it encompassed a wide variety of cultural elements and styles, including traditional musical styles as well as blues and jazz, traditional and new experimental forms in literature such as modernism and the new form of jazz poetry. This duality meant that numerous African-American artists came into conflict with conservatives in the Black intelligentsia. In this way, the Harlem Renaissance was not a monolithic movement, but a vibrant opportunity for the African American community to develop and explore the many facets of its identity.

Although the forms of expression varied widely, some common themes threaded throughout much of the work of the Harlem Renaissance. Black identity, the influence of slavery and emerging African-American folk traditions, institutional racism, the dilemmas inherent in performing and writing for elite White audiences, and the question of how to convey the experience of modern Black life in the urban North all found outlets in the work of the Harlem artists. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Three young women on the sidewalk in Harlem during the 1920s. For African Americans, Harlem was the center of culture – fashion, music, art, literature and politics – during the decade.

African American artists used their creativity to prove their humanity and demand equality. The Harlem Renaissance led to more opportunities for Blacks to be published by mainstream houses. Many authors began to publish novels, magazines and newspapers during this time. The new fiction attracted a great amount of attention from the nation at large. Among authors who became nationally known were Claude McKay, Zora Neale Hurston, James Weldon Johnson, Alain Locke, and Langston Hughes.

The Harlem Renaissance was more than a literary or artistic movement. It also embraced a development of ethnic pride, as seen in the Back to Africa movement led by Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican-born political leader, publisher, journalist, entrepreneur, and orator. Garvey was President-General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and also President and one of the directors of the Black Star Line, a shipping and passenger line. Garvey was unique in advancing a philosophy to inspire a global mass movement and economic empowerment focusing on Africa known as Garveyism. Garveyism would eventually inspire others, ranging from the Nation of Islam to the Rastafari movement, which proclaim Garvey as a prophet, and the Black Power Movement of the 1960s.

At the same time, a different expression of ethnic pride, promoted by W. E. B. Du Bois, introduced the notion of the “talented tenth,” the African Americans who were fortunate enough to inherit money or property or obtain a college degree during the transition from Reconstruction to the Jim Crow period of the early twentieth century. According to Du Bois, these talented tenth were considered the finest examples of the worth of Black Americans as a response to the rampant racism of the period. Du Bois did not assign any particular leadership to the talented tenth, but in his writings he held them up as a model to be emulated. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Madam C. J. Walker in her car. She served as a symbol of the possibilities for African Americans, both men and women.

The artists and writers of the Harlem Renaissance rested primarily on a support system of Black patrons, Black-owned businesses and publications rather than on support from wealthy Whites. Among the most notable of these was Sarah Breedlove, better known as Madam C. J. Walker. Walker was an entrepreneur, philanthropist, and political and social activist. The first female self-made millionaire in the United States, she became one of the wealthiest self-made women in America and the wealthiest African-American woman in the country. Walker made her fortune by developing and marketing a line of beauty and hair products for black women. In addition to being a patron of the arts, Walker’s home served as a social gathering place for the African-American community.

Although the vibrant creativity of the Harlem Renaissance faded in the 1930s with the onset of the Great Depression, the movement had an enormous, lasting impact on the African American community in both New York City and the nation in general. The Harlem Renaissance was more than a literary or artistic movement. It possessed a certain sociological development, particularly through a new racial consciousness, through racial integration, and it helped lay the foundation for the later Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

CONCLUSION

W. E. B. Du Bois is rightfully remembered as a man who challenged Booker T. Washington’s accommodationist attitude toward White power and is properly accorded a position as one of the African American thinkers who gave birth to the ideas that became the Civil Rights Movement.

Du Bois’ New Negro was a different kind of person than Washington’s ideal African American citizen. But how so? What did it mean to be a New Negro in the 1920s? What was new or reborn?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The 1920s marked a time when African-Americans were moving and changing their ideas about themselves and their place in American society.

After the end of Reconstruction, White leaders in the South established the Jim Crow system of segregation, which recreated the social order of the pre-Civil War Era with African Americans stuck firmly at the bottom.

The most prominent African American leader in the late 1800s was Booker T. Washington. He ran the Tuskegee Institute and argued that African Americans should find ways to become educated so that they could be productive members of society. He did not emphasize fighting for equality or equal rights.

In 1905, a group of African Americans formed the Niagara Movement. They wanted equal rights and founded the NAACP to fight for equality in the courts. Their leader was W. E. B. Du Bois, who offered a contrast to Booker T. Washington.

During WWI, thousands of African Americans moved out of the South to find jobs in factories in the North. This movement of people is called the Great Migration. They mostly settled in urban centers such as New York City, Chicago or Detroit. Although they did find higher paying jobs, they also found that segregation still existed in the North in the form of limits on where they could live and what jobs they could have.

A large number of the most creative and important leaders of the African American community settled in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City during the 1920s. They made music, wrote poetry and novels, danced, created artwork, and advocated for new political rights. This period of intense racial pride and activism was the Harlem Renaissance.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Booker T. Washington: African American educator in the late 1800s and early 1900s who led the Tuskegee Institute and argued that the best way for African Americans to advance their position in society was to learn useful skills rather than agitate for equality and justice. This was the Atlanta Compromise.

W. E. B. Du Bois: African American author, political leader and intellectual who led the Niagara Movement and published The Crisis. He believed that African Americans should reject the Atlanta Compromise and fight for equality and justice.

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP): Organization dedicated to promoting African American rights through the justice system. It was established in 1909 as part of the Niagara Movement.

Claude McKay: Poet of the Harlem Renaissance. His most famous poem is “If We Must Die.”

Zora Neale Hurston: Author of the Harlem Renaissance. Her novels celebrated the life of everyday African Americans.

James Weldon Johnson: Poet of the Harlem Renaissance. He wrote “Life Every Voice and Sing.”

Alain Locke: Author, philosopher, teacher and patron of the arts during of the Harlem Renaissance.

Langston Hughes: Most famous poet of the Harlem Renaissance.

Marcus Garvey: Jamaican-born entrepreneur and leader during the 1920s who led the Universal Negro Improvement Association.

United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA): Organization founded by Marcus Garvey that encourage cooperation among all African people and people of African descent in the world. They also supported the independence movement in Jamaica.

Madam C. J. Walker: Female African American entrepreneur who was an important patron of the arts and leader during the Harlem Renaissance. She rose from poverty and made her fortune selling cosmetic products designed for African American women.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Jim Crow: The nickname for a system of laws that enforced segregation. For example, African Americans had separate schools, rode in the backs of busses, could not drink from White drinking fountains, and could not eat in restaurants or stay in hotels, etc.

Atlanta Compromise: Belief that the best way for African Americans to advance their position in society was to learn useful skills rather than agitate for equality and justice. It was promoted by Booker T. Washington in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The name derives from a speech.

Talented Tenth: W. E. B. Du Bois’s idea that 10% of African Americans had the skills, education, and motivation to be the leaders of the community.

Redlining: Unofficial segregation in northern cities that occurred after the Great Migration in which realtors and banks refused to sell homes in certain neighborhoods to African American buyers.

New Negro: Idea that African Americans should assert themselves as members of American society, with literature, art, music and civil rights equal to all other people. It was popularized in the 1920s as part of the Harlem Renaissance and Niagara Movement. It was championed by W. E. B. Du Bois and contradicted Booker T. Washington’s Albany Compromise.

![]()

DOCUMENTS

Declaration of Principles: Statement published at the meeting of African American leaders in Niagara in 1905 calling for political, economic and social equality.

The Crisis: Journal published by W. E. B. Du Bois to promote the causes of African Americans.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Tuskegee Institute: Famous collage for African Americans led by Booker T. Washington.

Harlem: Neighborhood in Manhattan in New York City that became the home of African American politics and culture in the 1920s.

![]()

EVENTS

Niagara Movement: Movement in the African American community led by W. E. B. Du Bois to advocate for equality and racial justice. The NAACP was founded as part of this movement.

Great Migration: Movement of nearly two million African Americans out of the South to cities of the North in the 19-teens, largely to escape segregation and take advantage of job opportunities during World War I.

Back to Africa Movement: Movement championed by Marcus Garvey in the 1920s that argued for African Americans to assert ethnic pride and move to Africa.

![]()

COURT CASES

Plessy v. Ferguson: 1896 Supreme Court case in which the court declared that racially segregated schools and other public facilities were constitutional establishing the “separate but equal” doctrine. It was overturned in the Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954.

Did the Tuskegee Institute ever face racist hate crimes?

It’s sad how even after all those fights and laws passed, Blacks were still subjected to racial hatred.

The two views from Washington and Du Bois continues today for new immigrants. When people from other countries move to the US, many are in a dilemma of either changing to fit in better or staying true to their own culture.

Without the Harlem Renaissance would music like Jazz exist in society today?

How has the Harlem Renaissance still been recognized in recent events involving African Americans?

Did the W. E. B. stand for anything in the Du Bois?

Why is it that they enjoyed the idea of the Harlem renaissance entertainment yet they still embraced Jim Crow laws and being “separate but equal”?

Did outsiders know about the Harlem Renaissance? If so, did they ever join the Movement, or was there oppositions towards it?

Love seeing African American artists using their platform for good girlboss moment

How much did the Harlem Renaissance actually help African Americans show white people that they deserved to be treated as equals? How did it impact civil rights movements from the communities?

What happened to W. E. B. Du Bois?

Were the African-American tenements better or worse than the European tenements?

How did people respond to the Harlem Renaissance?

How different would it be if the people were to follow or listen more closely to what Booker T. Washington said in his speech?

Was it an easy road for Madam C. J. Walker?? What complications did she face?

Would Washington’s way ever have worked?

Did Booker T. Washington receive hate because of his speech?

Were there any African American groups or small organizations that did agree with Washington’s Atlanta Compromise? If so, what did they do? What became of them?

It’s so crazy to see the remnants of slavery that are still present today from the great migration through redlining and prejudices during the transition out of slavery.

Did Madam C.J Walker ever run into racial complications that would jeopardize her company?

Were there any white people that enjoyed specifically the culture that the blacks created for themselves?

Did those who attended Tuskegee want to learn things other than curriculum like cooking, farming, and housekeeping? Did any individuals want to learn subjects like math, english, or science?

During the Great Migration did some African Americans struggle to find jobs because of the color of they’re skin or did they get paid less?

Why did African American choose to move to the North during this time? Why not earlier?

Many of them faced economic problems with their jobs and their homes, after the war they sought to the North to gain better opportunities and escape Jim Crow laws. After the war, there had been many job openings for African Americans.

Was the Harlem Renaissance similar to the Enlightenment? In both periods, the people there had shared their different ideas about each other, what they felt was right and more, and I feel there is a connection between these two periods.

I guess it was kind of an African-American englightenment. Yes, they were able to share their different ideas to their community and they were able to work together as a whole to fight for their community too.

What are some examples of people in the Black intelligentsia? What did they think about the Harlem Renaissance?

What outcome would have resulted if T. Booker’s Washington beliefs were championed greatly by everyone?

I think the outcome would be very repressive for all those who did not champion the beliefs of Booker T. Washington. His beliefs were very accommodating towards the Whites and that is why many of them agreed with his beliefs. This would have led to many African Americans to just show that they can be productive members of society but they would not be seen as equals. This would mean that in that time period and possibly even now, African Americans would not be seen as equals and would not have achieved the civil rights they did in current day society.

Did wealthy industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie and John D Rockefeller providing funds for Washington’s self-help programs have an influence?