TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

The First World War was a total war. In previous wars, expectations were placed on civilians for food and clothing, but modern communication and technology brought about by the industrial revolution required an all-out effort from the entire population. Without the support of civilians, failure was certain. Governments used every means of communication imaginable to spread pro-war propaganda. American efforts geared to winning World War I amounted to nothing less than a national machine.

During peacetime, businesses buy and sell, invest, succeed and fail on their own, with little or no interference from the government. That is what has made America’s economy so powerful for so long. However, during wartime, the wheels of commerce needed to be tuned toward production of military equipment, and the nation’s food supply, as well as the means of transportation and communication all needed to be coordinated to ensure maximum support for the war effort. Victory depended on total support for the war.

The result was a tremendous increase in federal power as the government took over the job of managing the food supply, the railroad systems, the communications networks, industry, labor relations, and even took on the role of advertiser in order to promote pro-war attitudes among the public. Never before in American history had the government been so powerful.

Was this a good idea? Government control of the economy seemed like a way to increase the nation’s chances of winning the war, but it also limited the ability of individuals to make economic decisions for themselves. The government even passed laws limiting what people could say or write in their effort to promote 100% support for the war.

What do you think? Are restrictions on basic freedoms justified in times of crisis?

MOBILIZING THE NATION

Wilson knew that the key to America’s success in war lay largely in its preparation. With both the Allied and enemy forces entrenched in battles of attrition in thousands of miles of trenches, and supplies running low on both sides, the United States needed, first and foremost, to secure enough men, money, food, and supplies to be successful.

In 1917, when the United States declared war on Germany, the army ranked seventh in the world in terms of size, with an estimated 200,000 enlisted men. In contrast, at the outset of the war in 1914, the German force included 4.5 million men, and the country ultimately mobilized over eleven million soldiers over the course of the entire war.

To compose a fighting force, Congress passed the Selective Service Act in 1917, which required all men aged 21 through 30 to register for the draft. In 1918, the act was expanded to include all men between 18 and 45. By way of the draft, the government could enlist men into the military whether they volunteered or not. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Men lined up to register for the draft early in the war.

Through a campaign of patriotic appeals, as well as an administrative system that allowed men to register at their local draft boards rather than directly with the federal government, over ten million men registered for the draft on the very first day. By the war’s end, twenty-two million men had registered for the draft. Five million of these men were actually drafted, another 1.5 million volunteered, and over 500,000 additional men signed up for the navy or marines. In all, two million men participated in combat operations overseas. Among the volunteers were also twenty thousand women, a quarter of whom went to France to serve as nurses or in clerical positions.

Certainly, many Americans were enthusiastic about supporting their country. Some of the most eager were recent immigrants from Europe and their children, since serving in the army was a way to demonstrate patriotism and love for their new country. However, the draft also provoked opposition, and almost 350,000 eligible Americans refused to register for military service. About 65,000 of these defied the conscription law as conscientious objectors, mostly on the grounds of their deeply held religious beliefs. Such opposition was not without risks, and whereas most objectors were never prosecuted, those who were found guilty at military hearings received stiff punishments. Courts handed down over two hundred prison sentences of twenty years or more, and seventeen death sentences for Americans who refused to join the military.

There was a sinister side to the war hysteria. Wars seem to bring out the worst prejudices in people, and since many Americans could not discern between enemies abroad and enemies at home, German-Americans became targets for countless hate crimes. On a local level, schoolchildren were pummeled on schoolyards, and yellow paint was splashed on front doors. One German-American was lynched by a mob in Collinsville, Illinois.

Anti-German sentiment was so extreme in some places is strikes modern students of history as silly. Colleges and high schools stopped teaching the German language. The city of Cincinnati banned pretzels, and esteemed city orchestras refused to play music by German composers. Hamburgers, sauerkraut, and frankfurters became known as liberty meat, liberty cabbage, and hot dogs. Even the temperance movement received a boost by linking beer drinking with support for Germany.

THE POWER OF GOVERNMENT

World War I led to important changes in the federal government’s relationship with business. Notably, the government gave itself enormous power to direct and regulate private enterprise.

With the size of the army growing, the government needed to ensure that there were adequate supplies, in particular food and fuel, for both the soldiers and the home front. Concerns over shortages led to the passage of the Lever Act, also called the Food and Fuel Control Act, which empowered the president to control the production, distribution, and price of all food products during the war effort. Using this law, Wilson created both a Fuel Administration and a Food Administration. The Fuel Administration, run by Harry Garfield, created the concept of fuel holidays, encouraging civilian Americans to do their part for the war effort by rationing fuel on certain days. Garfield also implemented daylight saving time for the first time in American history, shifting the clocks to allow more productive daylight hours. Herbert Hoover coordinated the Food Administration, and he too encouraged volunteer rationing by invoking patriotism. With the slogan “food will win the war,” Hoover encouraged “Meatless Mondays,” “Wheatless Wednesdays,” and other similar reductions, with the hope of rationing food for military use. Primary Source: Propaganda Poster

Primary Source: Propaganda Poster

While British, French, German and other European farmers were fighting fighting, American farmers provided the food that save the lives of much of the population of Europe.

Wilson also created the War Industries Board, run by Bernard Baruch, to ensure adequate military supplies. The War Industries Board had the power to direct shipments of raw materials, as well as to control government contracts with private producers. Baruch used lucrative contracts with guaranteed profits to encourage several private firms to shift their production over to wartime materials. For those firms that refused to cooperate, Baruch’s government control over raw materials provided him with the necessary leverage to convince them to join the war effort, willingly or not.

As a way to move all the personnel and supplies around the country efficiently, Congress created the U.S. Railroad Administration. Wilson appointed William McAdoo, the Secretary of the Treasury, to lead this agency, which had extraordinary war powers to control the entire railroad industry, including traffic, terminals, rates, and wages.

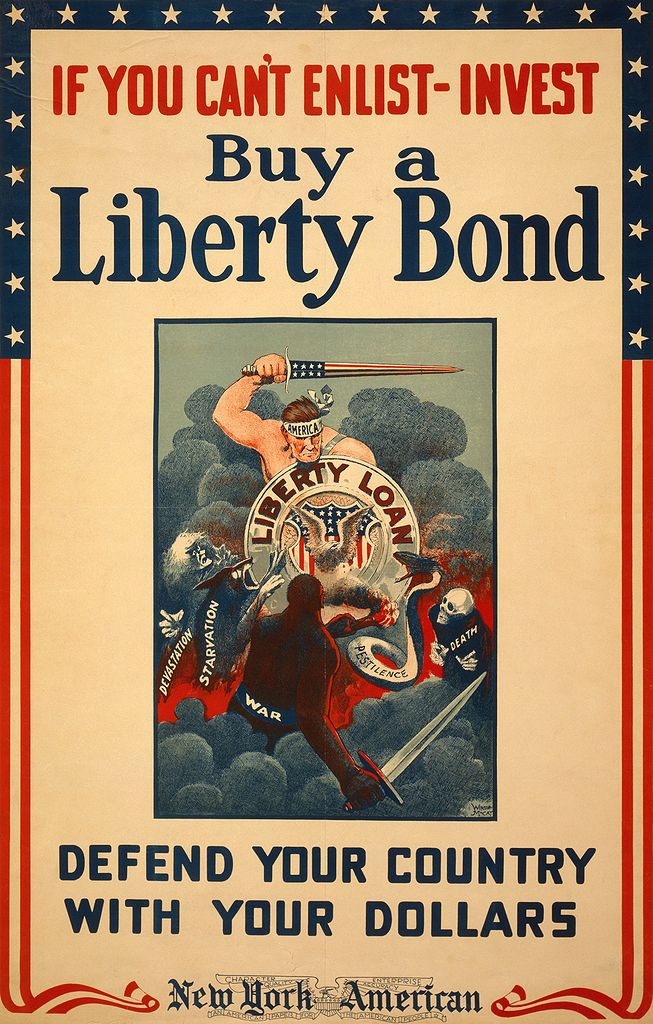

Almost all the practical steps were in place for the United States to fight a successful war. The only step remaining was to figure out how to pay for it. The war effort was costly, with an eventual price tag in excess of $32 billion by 1920, and the government needed to finance it. The Liberty Loan Act allowed the federal government to sell liberty bonds to the American public, extolling citizens to “do their part” to help the war effort and bring the troops home. The government ultimately raised $23 billion through liberty bonds. Additional monies came from the government’s use of federal income tax revenue, which was made possible by the passage of the Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1913. With the financing, transportation, equipment, food, and men in place, the United States was ready to enter the war. The next piece the country needed was public support.

LIMITING FREEDOMS

Although all the physical pieces required to fight a war fell quickly into place, the question of national unity was another concern. The American public was divided on the subject of entering the war. While many felt it was the only choice, others protested strongly, feeling it was not America’s war to fight.

Wilson needed to ensure that a nation of diverse immigrants, with ties to both sides of the conflict, thought of themselves as American first, and their home country’s nationality second. Wilson created the Committee on Public Information under the direction of George Creel to create and disseminate propaganda. Creel used every possible medium imaginable to raise American consciousness. He organized rallies and parades. He commissioned popular musicians to write patriotic songs intended to stoke the fires of American nationalism. One song, Over There became an overnight standard. Artists illustrated dozens of posters urging Americans to do everything from preserving coal to enlisting in the service. The famous image of Uncle Sam staring at young American men declaring “I Want You for the U.S. Army” was a creation of the World War I propaganda campaign. An army of Four-Minute Men swept the nation making short, but poignant, powerful speeches. Films and plays added to the fervor. The Creel Committee effectively raised national spirit and engaged millions of Americans in the business of winning the war. Primary Source: Propaganda Poster

Primary Source: Propaganda Poster

Images like these were important elements of the government’s propaganda campaign to convince Americans to support the war effort.

Still there were dissenters. The American Socialist Party condemned the war effort. Many Irish-Americans displayed contempt for Britain, who they saw as an enemy rather than an ally. Millions of immigrants from Germany and Austria-Hungary were forced to support initiatives that could destroy their homelands. Although all of this dissent was rather small, the government stifled wartime opposition by law with the passing of the Espionage and Sedition Acts of 1917. Anyone found guilty of criticizing the government war policy or hindering wartime directives could be sent to jail. Many cried that this was a flagrant violation of precious civil liberties, including the right to free speech. The Supreme Court handed down a landmark decision on this issue in the Schenck v. United States verdict. The majority court opinion ruled that should an individual’s free speech present a “clear and present danger” to others, the government could impose restrictions or penalties. Schenck was arrested for sabotaging the draft. The Court ruled that his behavior endangered thousands of American lives and upheld his jail sentence. Socialist Party leader Eugene V. Debs was imprisoned and ran for President from his jail cell in 1920. He polled nearly a million votes.

ORGANIZED LABOR SUPPORTS THE WAR

After decades of limited involvement in the challenges between management and organized labor, the need for peaceful and productive industrial relations prompted the federal government during wartime to invite organized labor to the negotiating table. Samuel Gompers, head of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), sought to capitalize on these circumstances to better organize workers and secure for them better wages and working conditions. His efforts also solidified his own base of power. The increase in production that the war required exposed severe labor shortages in many states, a condition that was further exacerbated by the draft, which pulled millions of young men from the active labor force.

Wilson only briefly investigated the longstanding animosity between labor and management before ordering the creation of the National Labor War Board in April 1918. Quick negotiations with Gompers and the AFL resulted in a promise. Labor unions pledged not to strike for the duration of the war in exchange for the government’s protection of workers’ rights to organize and bargain collectively. The federal government kept its promise and promoted the adoption of an eight-hour workday (which had first been adopted by government employees in 1868), a living wage for all workers, and union membership. As a result, union membership skyrocketed during the war, from 2.6 million members in 1916 to 4.1 million in 1919. In short, American workers received better working conditions and wages as a result of the country’s participation in the war. However, their economic gains were limited. While prosperity overall went up during the war, it was enjoyed more by business owners and corporations than by the workers themselves. Even though wages increased, inflation offset most of the gains. Prices in the United States increased an average of 15% to 20% annually between 1917 and 1920. Individual purchasing power actually declined during the war due to the substantially higher cost of living. Business profits, in contrast, increased by nearly a third during the war.

WOMEN IN WARTIME

For women, the economic situation was complicated by the war, with the departure of wage-earning men and the higher cost of living pushing many toward less comfortable lives. At the same time, however, wartime presented new opportunities for women in the workplace. More than one million women entered the workforce for the first time as a result of the war, while more than eight million working women found higher paying jobs, often in industry. Many women also found employment in what were typically considered male occupations, such as on the railroads, where the number of women tripled, and on assembly lines.

After the war ended and men returned home and searched for work, women were fired from their jobs, and expected to return home and care for their families. Furthermore, even when they were doing men’s jobs, women were typically paid lower wages than male workers, and unions were ambivalent at best, and hostile at worst, to women workers. Even under these circumstances, wartime employment familiarized women with an alternative to a life in domesticity and dependency, making a life of employment, even a career, plausible for women. When, a generation later, World War II arrived, this trend would increase dramatically. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Women found jobs open to them during wartime that had never been open before.

One notable group of women who exploited these new opportunities was the Women’s Land Army of America. First during World War I, then again in World War II, these women stepped up to run farms and other agricultural enterprises, as men left for the armed forces. Known as Farmerettes, some twenty thousand women, mostly college educated and from larger urban areas, served in this capacity. Their reasons for joining were manifold. For some, it was a way to serve their country during a time of war. Others hoped to capitalize on the efforts to further the fight for women’s suffrage.

Also of special note were the approximately thirty thousand American women who served in the military, as well as a variety of humanitarian organizations, such as the Red Cross and YMCA, during the war. In addition to serving as military nurses, American women also served as telephone operators in France. Of this latter group, 230 of them, known as “Hello Girls,” were bilingual and stationed in combat areas. Over eighteen thousand American women served as Red Cross nurses, providing much of the medical support available to American troops in France. Close to three hundred nurses died during service. Many of those who returned home continued to work in hospitals and home healthcare, helping wounded veterans heal both emotionally and physically from the scars of war.

AFRICAN AMERICANS AND THE DOUBLE V CAMPAIGN

African Americans also found that the war brought upheaval and opportunity. African Americans composed 13% of the enlisted military, with 350,000 men serving. Colonel Charles Young of the Tenth Cavalry division served as the highest-ranking African American officer. African Americans served in segregated units and suffered from widespread racism in the military hierarchy, often serving in menial or support roles.

Some troops saw combat, however, and were commended for serving with valor. The 369th Infantry, for example, known as the Harlem Hellfighters, served on the frontline of France for six months, longer than any other American unit. One hundred seventy-one men from that regiment received the Legion of Merit for meritorious service in combat. The regiment marched in a homecoming parade in New York City, was remembered in paintings, and was celebrated for bravery and leadership. The accolades given to them, however, in no way extended to the bulk of African Americans fighting in the war.

On the home front, African Americans, like American women, saw economic opportunities increase during the war. Nearly 350,000 African Americans found work in the steel, mining, shipbuilding, and automotive industries. African American women also sought better employment opportunities beyond their traditional roles as domestic servants. By 1920, over 100,000 women had found work in diverse manufacturing industries, up from 70,000 in 1910. Despite such opportunities, racism continued to be a major force in both the North and South. Worried about the large influx of African Americans into their cities, several municipalities passed residential codes designed to prohibit African Americans from settling in certain neighborhoods. Race riots also increased in frequency: In 1917 alone, there were race riots in twenty-five cities, including East Saint Louis, where thirty-nine blacks were killed. In the South, White business and plantation owners feared that their cheap workforce was fleeing the region, and used violence to intimidate blacks into staying. According to NAACP statistics, recorded incidences of lynching increased from thirty-eight in 1917 to eighty-three in 1919. These numbers did not start to decrease until 1923, when the number of annual lynchings dropped below thirty-five for the first time since the Civil War. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Members of the 369th Infantry, better known as the Harlem Hellfighters. Like many African American men during the war they were fighting both against the Kaiser’s army on the field in Europe and against prejudice at home.

CONCLUSION

Wars are instigators for tremendous change, and although World War I was not fought on American soil, it did bring about enormous change for many Americans. Women and African Americans saw new opportunities, and labor unions found an unexpected boost from the need to keep factories open during the war.

By far, however, the most significant change was relationship Americans had with their government. Before the war, the only connection most people had with the federal government was when they went to the post office, or every other year on election day when they went to vote. World War I changed that forever. Because of the war, government took on the power to regulate such everyday things as the price of milk, and what you could or could not say to your friends.

Undoubtedly, the nation needed to take appropriate steps to win once having committed itself to the fight, but was such deep involvement in everyday life appropriate? Were laws such as the Espionage and Sedition Acts or regulations on food prices and railroad schedules acceptable, or is there nothing, not even war, that warrants such direct involvement in private life and private business?

What do you think? Are restrictions on basic freedoms justified in times of crisis?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: World War I had profound impacts on the United States. Although there was never any fighting on American soil, it led to the expansion of the government, new opportunities for women and African Americans, as well as regrettable restrictions of the freedom of speech.

Americans were enthusiastic about joining the army. For many recent immigrants and their children, joining the fight was a way to demonstrate their love for their new country. A draft was implemented. There were a few conscientious objectors.

Anti-German feelings were common. There were many German immigrants and they faced discrimination. Schools stopped teaching German and German foods were renamed at restaurants.

The federal government gained in both size and power during the war. Business leaders and government officials collaborated to set prices and organize railroad schedules in support of the war effort. Future president Herbert Hoover organized the food industry and the United States fed both its own people and the people of Europe during the war.

To pay for the war, the government raised money by selling liberty bonds.

One of the dark sides to World War I were laws passed to limit First Amendment freedoms. The Espionage and Sedition Acts made criticizing the government and the war effort illegal. In the case of Schenck v. United States, the Supreme Court upheld these restrictions.

The war effort was good for organized labor. Labor unions worked closely with government officials who wanted to avoid strikes. It was during the war that the 8-hour workday was implemented. Pay went up as well.

Women took some jobs in factories and supported the war effort as nurses and secretaries.

For African Americans, the war was a chance to demonstrate their bravery in battle. Although they served in segregated units, African Americans were fighting against both Germany and discrimination back home. During the war, the need for factory workers in the North increased and thousands of African American families moved out of the rural South to the cities of the North to find work. This Great Migration significantly changed the racial makeup for the country.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Conscientious Objectors: People who refuse to join the military for personal, moral reasons, such as because of religious beliefs.

Herbert Hoover: Director of the Food Administration during World War I, and later president.

Bernard Baruch: Director of the War Industries Board during World War I.

George Creel: Director of the Committee on Public Information during World War I.

Harlem Hellfighters: Nickname for the 369th Infantry, a segregated unit of African-American soldiers during World War I.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Draft: System in which the government legally compels citizens to join the armed forces.

Daylight Savings Time: System in which clocks are moved forward one hour in the spring, thus allowing for more daylight hours during summer evenings.

Propaganda: Advertising created by the government to encourage citizens to think and act in ways the government wants.

Eight-Hour Day: Traditional work-day that was established during World War I.

![]()

GOVERNMENT AGENCIES

Fuel Administration: Government agency during World War I that managed rationing of gasoline and oil.

Food Administration: Government agency during World War I run by Herbert Hoover that managed rationing of food supplies.

War Industries Board: Government agency during World War I run by Bernard Baruch which directed production, distribution and wages. It is an example of significant government involvement in private industry.

U.S. Railway Administration: Government agency during World War I that managed the nation’s railway networks in order to support the war effort.

Committee on Public Information: Government agency created during World War I and run by George Creel to produce pro-war, pro-government propaganda.

National Labor War Board: Government agency created during World War I to negotiate with labor unions and prevent strikes.

Women’s Land Army: Government agency which employed women on farms to replace men who had joined the army.

![]()

SONGS

Over There: Most popular song during World War I.

![]()

COURT CASES

Schenck v. United States: Supreme Court ruling during World War I upholding the Espionage and Sedition Acts. It introduced the “clean and present danger” doctrine but is not widely considered to be a failure of the Court to preserve individual liberties.

![]()

LAWS

Selective Service Act: 1917 law that established the draft.

Lever Act / Food and Fuel Control Act: Law passed during World War I granting the president power to control production, distribution and price of food.

Liberty Loan Act: Law passed during World War I empowering the government to borrow billions of dollars by issuing war bonds.

Espionage and Sedition Acts: A pair of laws passed during World War I significantly restricting freedom of speech by making anti-war or anti-government speech illegal.