TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

In the beginning, Americans were farmers. Stories of the first settlers at Jamestown and the Pilgrims of Plymouth all recount learning to grow corn or tobacco. Southern planters grew cotton, and western farmers built windmills to pump water out of the ground to irrigate the prairies and produce the amber waves of grain immortalized in song.

But we are no longer a nation of farmers. In fact, as of 2012, 80% of Americans live in cities. How did this happen, and when? What caused all those farmers to give up on the land and fight the hustle and bustle of city life? And what happened to the cities when everyone moved in?

We think of our cities as multicultural places. People from many backgrounds mingle. The smells of foods from many homelands waft through the air. The air is often polluted, the streets noisy, the subways crowded. Where did all these people come from? When did we become more than just a nation of White Protestants?

Was it beneficial or harmful that we became a nation of multicultural cities?

THE NEW IMMIGRANTS

With the exception of Native Americans, America is a nation of immigrants, and the turn of the century was a period of enormous immigration. Immigrants shifted the demographics of America’s rapidly growing cities. Although immigration had always been a force of change in the United States, it took on a new character in the late nineteenth century.

Beginning in the 1880s, the arrival of immigrants from mostly southern and eastern European countries rapidly increased while the flow from northern and western Europe remained relatively constant. The previous waves of immigrants from northern and western Europe, particularly Germany, Great Britain, and the Nordic countries, were relatively well off, arriving in the country with some funds and often moving to the newly settled western territories. In contrast, the newer immigrants from southern and eastern European countries, including Italy, Greece, and Russia.

Many were pushed from their countries by a series of ongoing famines, by the need to escape religious, political, or racial persecution, or by the desire to avoid compulsory military service. They were also pulled by the promise of land, jobs, education, and religious freedom. Whatever the reason, these New Immigrants arrived without the education and finances of the earlier waves of immigrants, and settled more readily in the port towns where they arrived, rather than setting out to seek their fortunes in the West. By 1890, over 80% of the population of New York City would be either foreign-born or children of foreign-born parentage. Other cities saw huge spikes in foreign populations as well, though not to the same degree. Due in large part to the fact that Ellis Island, a major immigration station was in New York harbor, New York City’s status as a city of many cultures, was cemented at the turn of the century. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

The central building at Ellis Island in New York Harbor, photographed here in 1905.

THE IMPACT OF IMMIGRATION

The number of immigrants peaked between 1900 and 1910, when over nine million people arrived in the United States. To assist in the processing and management of this massive wave of immigrants, the Bureau of Immigration in New York City, which had become the official port of entry, opened Ellis Island in 1892. An equivalent station opened in San Francisco harbor at Angel Island where many immigrants from China were processed.

Today, nearly half of all Americans have ancestors who, at some point in time, entered the country through the portal at Ellis Island. Doctors or nurses inspected the immigrants upon arrival, looking for any signs of infectious diseases. Most immigrants were admitted to the country with only a cursory glance at any other paperwork. Roughly 2% of the arriving immigrants were denied entry due to a medical condition or criminal history. The rest would enter the country by way of the streets of New York, many unable to speak English and totally reliant on finding those who spoke their native tongue.

Seeking comfort in a strange land, as well as a common language, many immigrants sought out relatives, friends, former neighbors, townspeople, and countrymen who had already settled in American cities. This led to a rise in ethnic neighborhoods within the larger city. Little Italy, Chinatown, and many other communities developed in which immigrant groups could find everything to remind them of home, from local language newspapers to ethnic food stores. While these enclaves provided a sense of community to their members, they added to the problems of urban congestion, particularly in the poorest slums where immigrants could afford housing.

NATIVISM

The demographic shift at the turn of the century was later confirmed by the Dillingham Commission, created by Congress in 1907 to report on the nature of immigration in America. The commission reinforced this ethnic identification of immigrants and their simultaneous discrimination. The report put it simply:

These newer immigrants looked and acted differently. They had darker skin tone, spoke languages with which most Americans were unfamiliar, and practiced unfamiliar religions, specifically Judaism and Catholicism. Even the foods they sought out at butchers and grocery stores set immigrants apart. Because of these easily identifiable differences, new immigrants became easy targets for hatred and discrimination. If jobs were hard to find, or if housing was overcrowded, it was easy to blame the immigrants.

Growing numbers of Americans resented the waves of new immigrants, resulting in a backlash dubbed nativism by historians. This belief in the superiority of native-born Americans over immigrants, was led by the Reverend Josiah Strong who fueled the hatred and discrimination in his bestselling book, “Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis,” published in 1885. In a revised edition that reflected the 1890 census records, he clearly identified who he believed were undesirable immigrants, those New Immigrants from southern and eastern European countries, as a key threat to the moral fiber of the country, and urged all good Americans to face the challenge. Several thousand Americans answered his call by forming the American Protective Association, the chief political activist group to promote legislation curbing immigration into the United States. The group successfully lobbied Congress to adopt both an English language literacy test for immigrants, which eventually passed in 1917, and laid the groundwork for the subsequent limits on immigration.

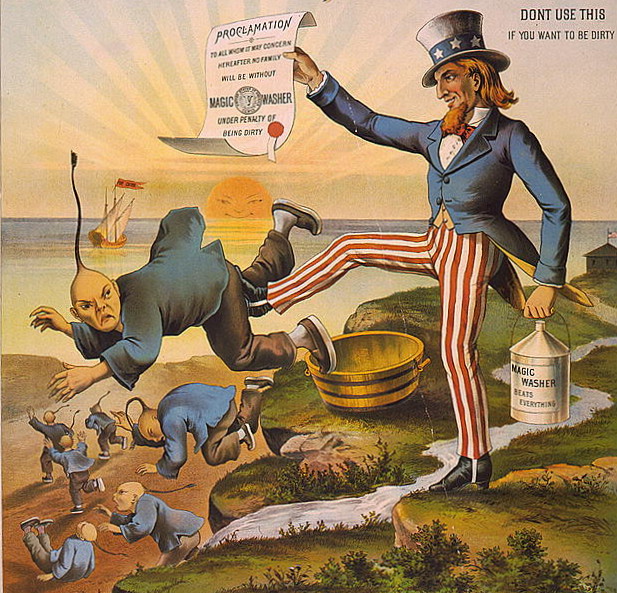

In 1882, Nativists convinced Congress to pass the Chinese Exclusion Act, barring this ethnic group in its entirety. 25 years later, Japanese immigration was restricted by executive agreement. These two Asian groups were the only ethnicities to be completely excluded from America.

But millions had already come. During the age when the Statue of Liberty beckoned the world’s “huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” American diversity mushroomed. Each brought pieces of an old culture and made contributions to a new one. Although many former Europeans swore to their deaths to maintain their old ways of life, their children did not agree. Most enjoyed a higher standard of living than their parents, learned English easily, and sought American lifestyles. At least to that extent, America was a melting pot. Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

This cartoon celebrates the Chinese Exclusion Act, showing Uncle Sam washing America by expelling Chinese immigrants.

URBANIZATION

Urbanization, the process of shifting from a country in which most people live on farms, to one where most people live in cities, occurred rapidly in the second half of the 19th Century in the United States for a number of reasons. The new technologies of the time led to a massive leap in industrialization, requiring large numbers of workers. New electric lights and powerful machinery allowed factories to run 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Workers were forced into grueling twelve-hour shifts, requiring them to live close to the factories.

While the work was dangerous and difficult, many were willing to leave behind the declining prospects of preindustrial agriculture in the hope of better wages in industrial labor. Furthermore, many of the New Immigrants settled and found work near the cities where they first arrived. The nation’s cities became an invaluable economic and cultural resource for people who missed their homelands.

Although cities such as Philadelphia, Boston, and New York sprang up from the initial days of colonial settlement, the explosion in urban population growth did not occur until the mid-1800s.

At this time, the attractions of city life, and in particular, employment opportunities, grew exponentially due to rapid changes in industrialization. Before the mid-1800s, factories, such as the early textile mills, had to be located near rivers and seaports, both for the transport of goods and the necessary water power. Production was dependent upon seasonal water flow, with cold, icy winters all but stopping river transportation entirely. The development of the steam engine transformed this need, allowing businesses to locate their factories near urban centers. The factories moved to where the most workers could be found, and workers followed the jobs, leading to a rapid rise in city populations.

Eventually, cities developed their own unique characters based on the core industry that spurred their growth. In Pittsburgh it was steel, in Chicago it was meat packing, in New York the garment and financial industries, and Detroit the automobiles reigned. But all cities at this time, regardless of their industry, suffered from the universal problems that rapid expansion brought with it, including concerns over housing and living conditions, transportation, and communication. These issues were almost always rooted in deep class inequalities, shaped by racial divisions, religious differences, and ethnic strife, and distorted by corrupt local politics.

GROWING OUT AND GROWING UP

As cities grew and sprawled outward, a major challenge was efficient mass transit within the city, from home to factories or shops, and then back again. Most transportation infrastructure was used to connect cities to each other, typically by rail or canal. Prior to the 1880s, transportation within cities was the usually the omnibus. This was a large, horse-drawn carriage, often placed on iron or steel tracks to provide a smoother ride. While omnibuses worked adequately in smaller, less congested cities, they were not equipped to handle the larger crowds that developed at the close of the century. The horses had to stop and rest and horse manure became an ongoing problem.

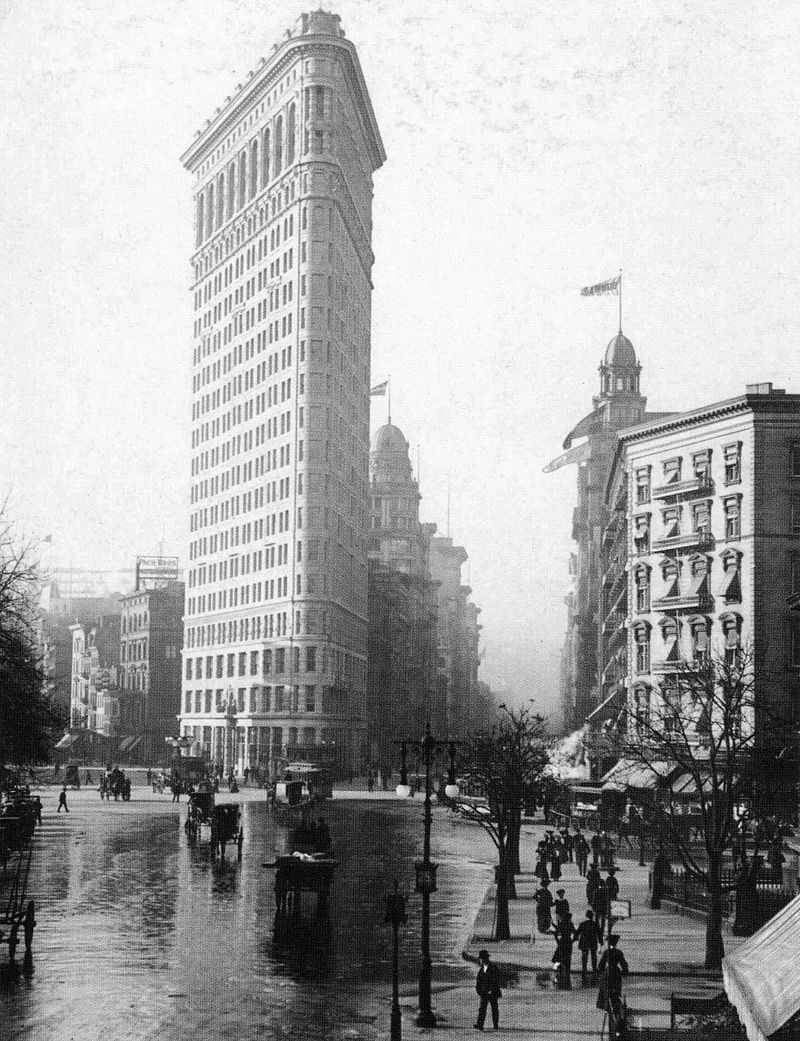

In 1887, Frank Sprague invented the electric trolley, which worked along the same concept as the omnibus, with a large wagon on tracks, but was powered by electricity rather than horses. The electric trolley could run throughout the day and night, like the factories and the workers who fueled them. But it also modernized less important industrial centers, such as the southern city of Richmond, Virginia. As early as 1873, San Francisco engineers adopted pulley technology from the mining industry to introduce cable cars and turn the city’s steep hills into elegant middle-class communities. However, as crowds continued to grow in the largest cities, such as Chicago and New York, trolleys were unable to move efficiently through the crowds of pedestrians. To avoid this challenge, city planners elevated the trolley lines above the streets, creating elevated trains, or L-trains, as early as 1868 in New York City, and quickly spreading to Boston in 1887 and Chicago in 1892. Transportation evolved one step further to move underground as subways. Boston’s subway system began operating in 1897, and was quickly followed by New York and other cities. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

The Flatiron Building, one of the world’s first skyscrapers which graces Fifth Avenue in New York City. It was completed in 1902.

With the development of efficient means of mass transportation, suburbs developed. Boston and New York spawned the first major suburbs. No metropolitan area in the world was as well served by railroad commuter lines at the turn of the twentieth century as New York, and it was the rail lines to Westchester from the Grand Central Terminal commuter hub that enabled its development. Westchester’s true importance in the history of American suburbanization derives from the upper-middle class development of villages including Scarsdale, New Rochelle and Rye serving thousands of businessmen and executives from Manhattan.

The last limitation that large cities had to overcome was the ever-increasing need for space. Eastern cities, unlike their Midwestern counterparts, could not continue to grow outward, as the land surrounding them was already settled. Geographic limitations such as rivers or the coast also hampered sprawl. In all cities, citizens needed to be close enough to urban centers to conveniently access work, shops, and other core institutions of urban life. The increasing cost of real estate made upward growth attractive, and so did the prestige that towering buildings carried for the businesses that occupied them. Workers completed the first skyscraper in Chicago, the ten-story Home Insurance Building, in 1885. Although engineers had the capability to go higher, thanks to new steel construction techniques, they required another vital invention in order to make taller buildings viable. In 1889, Elisha Otis delivered, with the invention of the safety elevator. This began the skyscraper craze, allowing developers in eastern cities to build and market prestigious real estate in the hearts of crowded metropolises.

CHALLENGES AND INNOVATIONS

As the country grew, certain elements led some towns to morph into large urban centers, while others did not. The following four innovations proved critical in shaping urbanization at the turn of the century: electric lighting, communication improvements, transportation, and the rise of skyscrapers. As people migrated for the new jobs, they often struggled with the absence of these basic services. Even necessities, such as fresh water and proper sanitation, often taken for granted in the countryside, presented a greater challenge in urban life.

Thomas Edison patented the incandescent light bulb in 1879. This development quickly became common in homes as well as factories, transforming how all social classes lived. Although slow to arrive in rural areas of the country, electric power became readily available in cities when the first commercial power plants began to open in 1882. When Nikola Tesla subsequently developed the AC (alternating current) system for the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company, power supplies for lights and other factory equipment could extend for miles from the power source. AC power transformed the use of electricity, allowing urban centers to physically cover greater areas.

Gradually, cities began to illuminate the streets with electric lamps to allow the city to remain alight throughout the night. No longer did the pace of life and economic activity slow substantially at sunset, the way it had in smaller towns. The cities, following the factories that drew people there, stayed open all the time.

The telephone, patented in 1876 by Alexander Graham Bell, greatly transformed communication both regionally and nationally. The telephone rapidly supplanted the telegraph as the preferred form of communication. By 1900, over 1.5 million telephones were in use around the nation, whether as private lines in the homes of some middle- and upper-class Americans, or jointly used party lines in many rural areas.

In the same way that electric lights spurred greater factory production and economic growth, the telephone increased business through the more rapid pace of demand. With telephones, orders could come constantly, rather than via mail order. More orders generated greater production, which in turn required still more workers. This demand for additional labor played a key role in urban growth, as expanding companies sought workers to handle the increasing consumer demand for their products.

Lights and communication might have illuminated the cities, but much of the urban poor, including a majority of incoming immigrants, lived in horrible housing. If the skyscraper was the jewel of the American city, the tenement was its boil. In 1878, a publication offered $500 to the architect who could provide the best design for mass housing. James Ware won the contest with his plan for a dumbbell tenement. This structure was thinner in the center than on its extremes to allow light to enter the building, no matter how tightly packed the tenements may be. Unfortunately, these vents were often filled with garbage. The air that managed to penetrate also allowed a fire to spread from one tenement to the next more easily.

The cities stank. The air stank, the rivers stank, the people stank. Although public sewers were improving, disposing of human waste was increasingly a problem. People used private cesspools, which overflowed with a long, hard rain. Old sewage pipes dumped the waste directly into the rivers or bays. These rivers were often the very same used as water sources.

Trash collection had not yet been systemized. Trash was dumped in the streets or in the waterways. Better sewers, water purification, and trash removal were some of the most pressing problems for city leadership. As the 20th Century dawned, many improvements were made, but the cities were far from sanitary. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

An example of a tenement building at the turn of the century. They were overcrowded, with many more people, and sometimes families, living in a single unit than the designers ever intended.

Because of the massive overcrowding and poor sanitation, disease was widespread. Cholera and Yellow Fever epidemics swept through the slums on a regular basis. Tuberculosis was a huge killer. Infants suffered the most. Almost 25% of babies born in late-1800s cities died before reaching the age of one. Sewer systems and the development of clean water delivery were some of the most important technological reforms of the time.

Poverty often breeds crime. Desperate people will often resort to theft or violence to put food on the family table when the factory wages would not suffice. Youths who dreaded a life of monotonous factory work and pauperism sometimes roamed the streets in gangs. Vices such as gambling, prostitution, and alcoholism were widespread. Gambling rendered the hope of getting rich quick. Prostitution provided additional income. Alcoholism furnished a false means of escape. The old system of town sheriffs were clearly inadequate for city life. The development of professional police forces is a legacy of the age of urbanization. In tandem with police forces, fire departments grew to meet the demand of city life. While small towns might be able to rely on a team of volunteer firefighters, or simply a bucket brigade of townspeople, cities required firefighters on duty day and night.

As the population became increasingly centered in urban areas while the century drew to a close, some reformers began to question the wisdom of moving into an entirely built environment. Was it wise to live in a world without trees, without lakes, rivers, or anything green?

Through the City Beautiful Movement, leaders such as Frederick Law Olmsted worked to bring nature back to the cities. Olmsted, one of the earliest and most influential designers of urban green space, and the original designer of Central Park in New York, worked to introduce the idea of the City Beautiful movement at the Columbian Exposition in 1893. From wide-open green spaces to brightly painted white buildings, connected with modern transportation services and appropriate sanitation, the White City of the Exposition set the stage for American urban city planning for the next generation. This model encouraged city planners to consider three principal tenets. First, create larger park areas inside cities. Second, build wider boulevards to decrease traffic congestion and allow for lines of trees and other greenery between lanes. And third, add more suburbs in order to mitigate congested living in the city itself. As each city adapted these principles in various ways, the City Beautiful movement became a cornerstone of urban development well into the twentieth century. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

The Polo Grounds, the first home of the New York Yankees baseball team. Professional baseball provided an inexpensive form of entertainment for the masses.

ENJOYING URBAN LIFE

Americans in cities wanted something to take their minds off of the hardships of daily life, and America’s entertainers rose to the challenge. One form of popular entertainment was vaudeville, large stage variety shows that included everything from singing, dancing, and comedy acts to live animals and magic. The vaudeville circuit gave rise to several prominent performers, including magician Harry Houdini, who began his career in these variety shows before his fame propelled him to solo acts. Although the new film industry would eventually kill off vaudeville, many of the most successful vaudeville performers moved from stage to screen.

A major form of entertainment for the working class was professional baseball. Club teams transformed into professional baseball teams with the Cincinnati Red Stockings, now the Cincinnati Reds, in 1869. Soon, professional teams sprang up in several major American cities. Baseball games provided an inexpensive form of entertainment, where for less than a dollar, a person could enjoy a double-header, two hot dogs, and a beer. But more importantly, the teams became a way for newly relocated Americans and immigrants of diverse backgrounds to develop a unified civic identity, all cheering for one team. By 1876, the National League had formed, and soon after, cathedral-style ballparks began to spring up in many cities. Fenway Park in Boston, Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, and the Polo Grounds in New York all became touch points where working-class Americans came together to support a common cause.

Other popular sports included prize-fighting, which attracted a predominantly male, working- and middle-class audience who lived vicariously through the triumphs of the boxers during a time where opportunities for individual success were rapidly shrinking, and college football, which paralleled a modern corporation in its team hierarchy, divisions of duties, and emphasis on time management.

CONCLUSION

As is clear, the turn of the century also turned Americans into city dwellers, and that shift was anything but easy. Overcrowding, pollution, poor sanitation, a lack of transportation, crime, fire, and overt racism all challenged the Americans, and newly arrived Americans, who built our cities. But, as we have come to expect of ourselves, those who struggled also persevered and developed ingenious ways to overcome seemingly insurmountable challenges. They built skyscrapers, streetcars, sewers and suburbs. They learned English, became citizens and gave us new foods, music, art and entertainment.

As America became and urban nation, Thomas Jefferson’s dream of a country built on yeoman farmers died. Americans would never again be tied to the land. We would be a nation of people who lived among paved streets, brick high rises, and electric lights instead of being regulated by the passing of the four seasons and the rising and setting of the sun.

What do you think? Was it beneficial or harmful for America to become a nation of cities?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The late 1800s and early 1900s was a time of enormous immigration and internal migration. For the first time more Americans lived in cities than on farms and inventors and leaders had to deal with the problems of growing cities.

Beginning in the 1880s, America experienced about four decades of massive immigration. These people are called the New Immigrants because they were different from earlier immigrants in important ways. First, they were poor and didn’t come with many skills. They left their homelands to escape poverty, war, famine and persecution. They came in search of jobs, religious freedom, and opportunities for their children. Most came from Southern and Eastern Europe. They were Italian, Greek, Romanian, Polish and Russian. Also, Chinese immigration increased.

New York City’s Ellis Island was a major immigration station and the city grew and expanded its reputation as a multicultural melting pot. Immigrants tended to settle into neighborhoods with support systems in place that they could rely on. The growth of ethnic enclaves such as Chinatown or Little Italy was a hallmark of urban growth at this time.

Some Americans did not like these new immigrants. Nativism once again was common. Efforts to make English the official language expanded. Anti-Semitism grew. Eventually, the KKK embraced these anti-immigrant ideas. The Chinese Exclusion Act officially banned all immigration from China, a victory for nativists. In contrast, the Statue of Liberty stood as a sign of welcome and symbol of all that immigrants hoped for in their adopted country.

Immigrants and migration from the countryside drove urbanization. It was around the year 1900 that America became a nation where more people lived in cities than on farms. As cities grew, so did problems associated with urban areas. Garbage and polluted water, crime, fire, poverty, and overcrowding were issues. In response, city leaders created professional police and fire departments.

Mass transit was developed. Cities built the first subways and trolley systems. Mass transit made it possible for people to live in suburbs and commute to work, so cities expanded outward. Otis’s safety elevator made skyscrapers possible, and cities expanded upward as well. Edison and Tesla’s work on electricity resulted in electric lights both inside and out. Bell’s telephone also revolutionized American city life.

Tenements were built to help house the poor. These low-rent apartments soon became overcrowded and emblematic of the problems with growing cities.

Cities built sewer systems to combat disease. The City Beautiful Movement encouraged the construction of parks such as Central Park in New York City. Americans went to baseball games for fun. Vaudeville performers travelled from place to place in the time before movies to entertain the masses.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

New Immigrants: The name for the immigrants who arrived in the United States in the late 1800s and early 1900s. They were different from the “Old Immigrants” in that they were often from Southern and Eastern Europe, were Catholic, Orthodox Christian or Jewish instead of Protestant. Unlike earlier groups of immigrants, they were also often poor and uneducated with few skills.

Josiah Strong: A leading nativist in the late 1800s. He disliked the New Immigrants and argued for literacy tests. He eventually helped end the waves of immigration that characterized the turn of the century.

Elisha Otis: Inventor of a safe electric elevator. His invention made skyscrapers possible.

Thomas Edison: Prolific American inventor. His creations included the electric lightbulb, phonograph (record player) and movie camera.

Nikola Tesla: Electrical engineer and inventor who developed alternating current that powers all of our electrical systems today.

Alexander Graham Bell: Inventor of the telephone and founder of the various Bell Telephone Companies.

Frederick Law Olmsted: Champion of the City Beautiful Movement and designer of many famous city parks including Central Park in New York City.

Harry Houdini: Famous vaudeville magician.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Push Factors: Reasons to leave a place. In the time of the New Immigrants these included religious persecution, war, famine and poverty.

Pull Factors: Reasons to come to a place. In the time of the New Immigrants these included jobs, religious freedom, education and land.

Nativism: A belief that people born in the United States are superior to immigrants.

Melting Pot: The idea that America is made up of a blending of many diverse cultural influences.

Urbanization: The process of developing cities.

City Beautiful Movement: A movement at the turn of the century to build parks in major cities. It was driven by the idea that humans should not live in an environment built of stone and concrete. Frederick Law Olmstead who designed Central Park in New York City was the most famous proponent of this idea.

Vaudeville: A form of entertainment popular in the early 1900s. It featured groups of travelling performers who put on played music, acted, or performed magic and similar acts. This form of entertainment died out as movies became popular.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Ellis Island: Major immigration station in New York Harbor.

Angel Island: Major immigration station in San Francisco Harbor.

Ethnic Neighborhoods: Areas in major cities where groups of immigrants concentrated. They usually had restaurants, grocery stores, newspapers, support organizations and churches that served the neighborhood’s immigrant population.

Statue of Liberty: Symbol of the pull factors that attracted the New Immigrants. It stands on an island in New York Harbor.

Suburbs: Cities built around a larger city. These developed because mass transit made it possible to live far from where a person worked.

Central Park: Famous park in Manhattan in New York City designed by Frederick Law Olmstead.

![]()

SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY

Mass Transit: Any form of transportation in cities designed to move many people. These include busses, subways, trolley cars and elevated trains.

Omnibus: A forerunner to the modern city bus. It was a carriage that ran on railroad tracks that was pulled by horses.

Electric Trolley: A trolley that ran on electricity.

Elevated Train: Similar to a subway, these trains ran on tracks built on bridges above city streets. The most famous is in Chicago and nicknamed the “L.”

Subway: A form of mass transit that has trains running in tunnels underground. The first in the United States was in Boston, but the most famous is in New York City.

Skyscraper: Tall buildings in cities. They made it possible for many more people to live and work in a smaller area.

Tenement: Public housing designed to provide inexpensive places to live in cities. Designed by James Ware, they were usually overcrowded, dirty, and places where disease was common.

Cholera: A disease common in major cities at the turn of the century caused by drinking polluted water. Sewer systems helped eliminate the disease.

Yellow Fever: A disease common in major cities at the turn of the century caused by the bite of mosquitos who bred in puddles of standing water. Paved streets and sewer systems reduced both the mosquitos and the disease.

Tuberculosis: A lung disease that spread in overcrowded cities at the turn of the century.

Sewer Systems: Major public works at the turn of the century designed to clean wastewater and provide clean drinking water.

![]()

LAWS & RESOLUTIONS

Chinese Exclusion Act: Law passed in 1882 ending immigration from China and preventing Chinese immigrants already in the United States from applying for citizenship.