TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

Just as they had done east of the Mississippi River, when White settlers pushed westward, they came into conflict with Native American tribes. Although the threat of attacks was quite slim and nowhere proportionate to the number of army actions directed against them, the occasional attack, often one of retaliation, was enough to fuel the popular fear of “savage Indians.” The clashes, when they happened, were indeed brutal, although most of the brutality occurred at the hands of the settlers.

Ultimately, the settlers, with the support of local militias and, later, with the federal government behind them, sought to remove the tribes from lands the Whites desired. The result was devastating for the Native American tribes who lacked the weapons and group cohesion to fight back against well-armed forces.

Modern Americans celebrate the nation as a land stretching from sea to shining sea, but that expansion came at a cost. The final conflict between the government and the Sioux Nations of the Northern Plains did indeed open the entire West to White settlement, but marked the absolute destruction of traditional Native American culture. Was this episode in America’s westward march a triumph or a tragedy? What do you think?

REMOVAL BY TREATY

Back East, the popular vision of the West was of a vast and empty land. Of course, this was an exaggerated depiction. On the eve of westward expansion, as many as 250,000 Native Americans, representing a variety of tribes, populated the Great Plains. Previous wars against these tribes in the early nineteenth century, as well as the failure of earlier treaties, had led to a general policy of the forcible removal of many tribes in the eastern United States. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 resulted in the infamous Trail of Tears, which saw nearly fifty thousand Seminole, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Creek Indians relocated west of the Mississippi River to what is now Oklahoma between 1831 and 1838. Building upon such a history, the government was prepared, during the rest of the century, to deal with tribes that settlers viewed as obstacles to expansion.

As settlers sought more land for farming, mining, and cattle ranching, the first strategy employed to deal with a perceived threat from resident Native Americans was to negotiate settlements to move tribes out of the path of White settlers onto designated lands called reservations. In 1851, the chiefs of most of the Great Plains tribes agreed to the First Treaty of Fort Laramie, which did just that. This agreement established distinct tribal borders, essentially codifying the reservation system. In return for annual payments of $50,000 to the tribes (originally guaranteed for fifty years, but later revised to last for only ten) as well as the hollow promise of noninterference from westward settlers, Native Americans agreed to stay clear of the path of settlement. Due to government corruption, many annuity payments never reached the tribes, and some who moved to the reservations were left destitute and near starving. In addition, within a decade, as the pace and number of western settlers increased, even designated reservations became prime locations for farms and mining. Rather than negotiating new treaties, settlers, oftentimes backed by local or state militia units, simply attacked the tribes out of fear or to force them from the land. Some Native American groups resisted, only to then face massacres.

THE SIOUX WARS

In 1862, frustrated and angered by the lack of annuity payments and the continuous encroachment on their reservation lands, Sioux in Minnesota rebelled in what became known as the Dakota War, killing the White settlers who moved onto their tribal lands. Over 1,000 White settlers were captured or killed in the attack, before an armed militia regained control. Of the 400 Sioux captured by government troops, 303 were sentenced to death, but President Lincoln intervened, releasing all but 38 of the men. The 38 who were found guilty were hanged in the largest mass execution in the country’s history, and the rest of the tribe was banished.

Settlers in other regions responded to news of this raid with fear and aggression. In Colorado, Arapahoe and Cheyenne tribes fought back against land encroachment. White militias then formed, decimating even some of the tribes that were willing to cooperate. One of the more vicious examples was near Sand Creek, Colorado, where Colonel John Chivington led a militia raid upon a camp in which the leader had already negotiated a peaceful settlement. The camp was flying both the American flag and the white flag of surrender when Chivington’s troops murdered close to one hundred people, the majority of them women and children, in what became known as the Sand Creek Massacre. For the rest of his life, Chivington would proudly display his collection of nearly one hundred scalps from that day. Subsequent investigations by the army condemned Chivington’s tactics and their results. However, the raid served as a model for some settlers who sought any means by which to eradicate the perceived threat from their Native American neighbors.

Hoping to forestall similar uprisings and all-out Indian wars, Congress commissioned a committee to investigate the causes of such incidents. The subsequent report of their findings led to the passage of two additional treaties: the Second Treaty of Fort Laramie and the Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek, both designed to move the remaining tribes to even more remote reservations. The Second Treaty of Fort Laramie moved the remaining Sioux to the Black Hills in the Dakota Territory and the Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek moved the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, and Comanche to Indian Territory, later to become the State of Oklahoma.

The agreements were short-lived, however. With the subsequent discovery of gold in the Black Hills, settlers seeking their fortune began to move upon the newly granted Sioux lands with support from federal cavalry troops. By the middle of 1875, thousands of White prospectors were illegally digging and panning in the area. The Sioux protested the invasion of their territory and the violation of sacred ground. The government offered to lease the Black Hills or to pay $6 million if the Sioux were willing to sell the land.

When the tribes refused, the government imposed what it considered a fair price for the land, ordered the Natives to move, and in the spring of 1876, made ready to force them onto the reservation. In the Battle of Little Bighorn, perhaps the most famous battle of the American West, Sioux chiefs Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse urged neighboring tribes to join in defense of their lands. At the Little Bighorn River, the army’s Seventh Cavalry, led by Colonel George Custer, sought a showdown. Driven by his own personal ambition, on June 25, 1876, Custer foolishly attacked what he thought was a minor Native encampment. Instead, it turned out to be the main Sioux force. The Sioux warriors, nearly 3,000 in strength, surrounded and killed Custer and 262 of his men and support units, in the single greatest loss of government troops to a Native American attack in the era of westward expansion. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Sitting Bull, one of the leaders of the Sioux at the Battle of Little Big Horn.

THE BUFFALO

The modern American bison, or buffalo as it is more commonly known, was a one-stop shop for the Plains tribes. Before the introduction of horses as part of the Columbian Exchange, bison were herded into large chutes made of rocks and willow branches and trapped in a corral called a buffalo pound and then slaughtered or stampeded over cliffs, called buffalo jumps. Both pound and jump archaeological sites are found in several places in the United States and Canada. In the case of a jump, large groups of people would herd the bison for several miles, forcing them into a stampede that drove the herd over a cliff. Horses taken from the Spanish were well-established in the nomadic hunting cultures by the early 1700s, and indigenous groups once living east of the Great Plains moved west to hunt the larger bison population. There, during the 1600s and 1700s, extensive intertribal warfare was waged over access to hunting grounds opened for the first time because of the access to horses.

For the government and White settlers alike, destruction of the great bison herds of the Plains was equivalent to the destruction of the Plains tribes, and the second half of the 1800s saw the near complete extinction of the species. For settlers of the Plains region, bison hunting served as a way to increase their economic stake in the area. Trappers and traders made their living selling buffalo fur. In the winter of 1872–1873, more than 1.5 million buffalo were put onto trains and moved eastward. In addition to the potential profits from buffalo leather, which was commonly used to make machinery belts and army boots, buffalo hunting forced Natives to become dependent on beef from cattle. General Winfield Scott Hancock, for example, reminded several Arapaho chiefs at Fort Dodge in 1867, “You know well that the game is getting very scarce and that you must soon have some other means of living; you should therefore cultivate the friendship of the white man, so that when the game is all gone, they may take care of you if necessary.”

Commercial bison hunters also emerged at this time. Military forts supported hunters, who would use their civilian sources near their military base. Though officers hunted bison for food and sport, professional hunters made a far larger impact in the decline of bison population. Officers stationed in Fort Hays and Wallace even had bets in their “buffalo shooting championship of the world”, between “Medicine Bill” Comstock and “Buffalo Bill” Cody. Some of these hunters would engage in mass bison slaughter in order to make a living.

The army sanctioned and actively endorsed the wholesale slaughter of bison herds. The federal government promoted bison hunting to allow ranchers to range their cattle without competition and primarily to weaken the Native American population. Without the bison, the people of the plains had no choice but to leave the land or starve to death. One of the biggest advocates of this strategy was General William Tecumseh Sherman. On June 26, 1869, the Army Navy Journal reported that, “General Sherman remarked, in conversation the other day, that the quickest way to compel the Indians to settle down to civilized life was to send ten regiments of soldiers to the plains, with orders to shoot buffaloes until they became too scarce to support the redskins.”

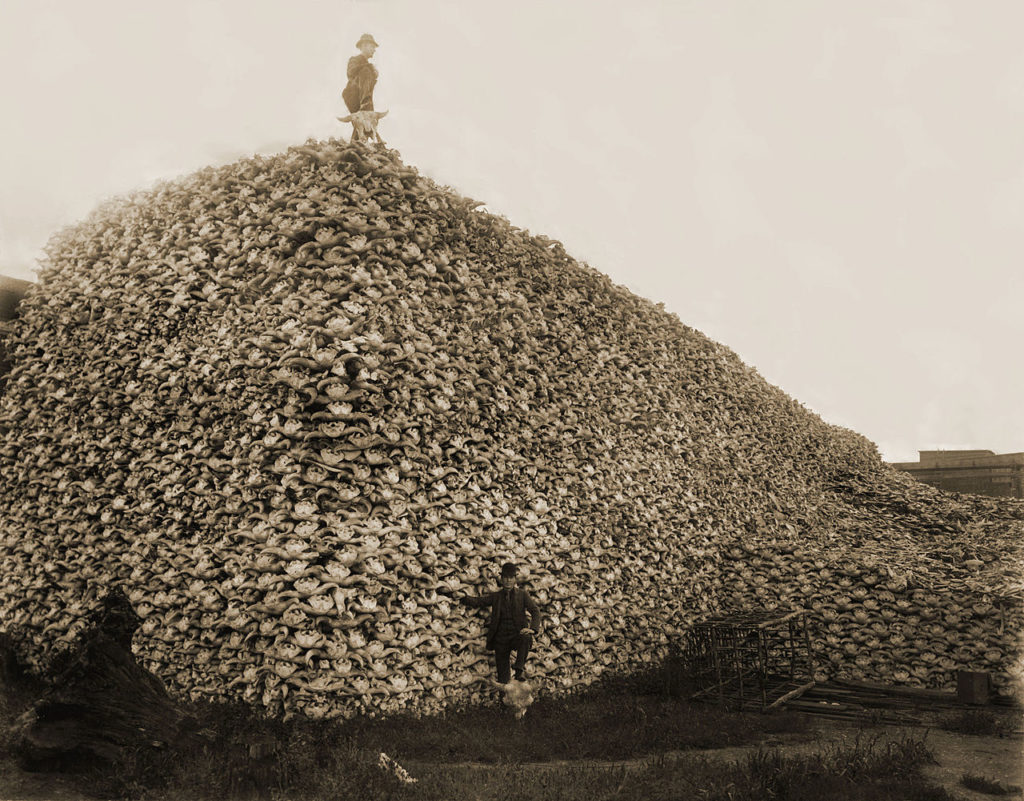

As railroads expanded, military troops and supplies were able to be transported more efficiently to the Great Plains. Some railroads hired commercial hunters to feed their laborers. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, for example, was hired by the Kansas Pacific Railroad for this reason. Hunters began arriving in masses, and trains would slow down so men could climb aboard the roofs of trains or fire shots at herds from outside their windows. As a description of such a hunt from Harper’s Weekly noted, “The train is ‘slowed’ to a rate of speed about equal to that of the herd; the passengers get out fire-arms which are provided for the defense of the train against the Indians, and open from the windows and platforms of the cars a fire that resembles a brisk skirmish.” The railroad industry also wanted bison herds culled or eliminated. Herds of bison on tracks could damage locomotives when the trains failed to stop in time and encounters with bison herds could delay a train for days. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Bison bones, including these sculls, were collected after the great hunts to be used for fertilizer. This photograph gives modern historians a sense of the scope of the slaughter.

The destruction of bison signaled the end of the Indian Wars, and consequently their movement towards reservations where, having no knowledge of agriculture, they become dependent on government rations as source of food. The last Native American bison hunt was in 1882.

When the Texas legislature proposed a bill to protect the bison, General Sheridan disapproved of it, stating, “These men have done more in the last two years, and will do more in the next year, to settle the vexed Indian question, than the entire regular army has done in the last forty years. They are destroying the Indians’ commissary. And it is a well known fact that an army losing its base of supplies is placed at a great disadvantage. Send them powder and lead, if you will; but for a lasting peace, let them kill, skin and sell until the buffaloes are exterminated. Then your prairies can be covered with speckled cattle.”

The mass buffalo slaughter had an ecological impact as well. Unlike cattle, bison were naturally fit to thrive in the Great Plains environment. The bison’s giant heads are naturally fit to drive through snow and make them far more likely to survive harsh winters. Additionally, bison grazing helps to cultivate the prairie, making it ripe for hosting a diverse range of plants. Cattle, on the other hand, eat through vegetation and limit the ecosystem’s ability to support a diverse range of species. Agricultural and residential development of the prairie is estimated to have reduced the prairie to 0.1% of its former area. The plains region has lost nearly one-third of its prime topsoil since the onset of the buffalo slaughter. Cattle are also causing water to be pillaged at rates that are depleting many aquifers of their resources. Research now suggests that the absence of native grasses leads to topsoil erosion which was a main contributor of the dust bowl and black blizzards of the 1930s. Although their strategy of destroying the bison to force Native Americans onto reservation worked to the White’s advantage, it would have been better for them in the end to adapt to the ways of their Native American neighbors and raise bison instead of cattle.

Ultimately, bison were hunted down to roughly 300 individuals before a few ranchers and zoos began working to preserve the species. Today, about 500,000 bison currently exist on private lands and around 30,000 on public lands. Approximately 15,000 bison are considered wild, free-range bison not primarily confined by fencing. Bison is the national mammal, a symbol of the many sides of America and its complicated history.

THE LAST OF THE FREE TRIBES

Despite their success at Little Bighorn, neither the Sioux nor any other Plains tribe followed this battle with any other armed encounter. Perhaps due to the loss of bison, or due to fear of returning troops, most accepted payment for forcible removal from their lands. Sitting Bull himself fled to Canada, although he later returned in 1881 and subsequently worked in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

By the end of the 1880s, a general consensus seem to have been reached among many politicians in Washington that the assimilation of Native Americans into American culture was preferable to slaughter on the battlefield and that it was the time for them to leave behind their tribal landholding, reservations, traditions and ultimately their identities. On February 8, 1887, the Dawes Act was signed into law by President Grover Cleveland in pursuit of these goals.

The Dawes Act divided tribal reservations into plots of land for individual households, which White reformers had hoped would break up tribes as social units, encourage individualism, help convert nomadic Natives into farmers, reducing the cost of administering reservations, and open the remainder of the West to White settlers.

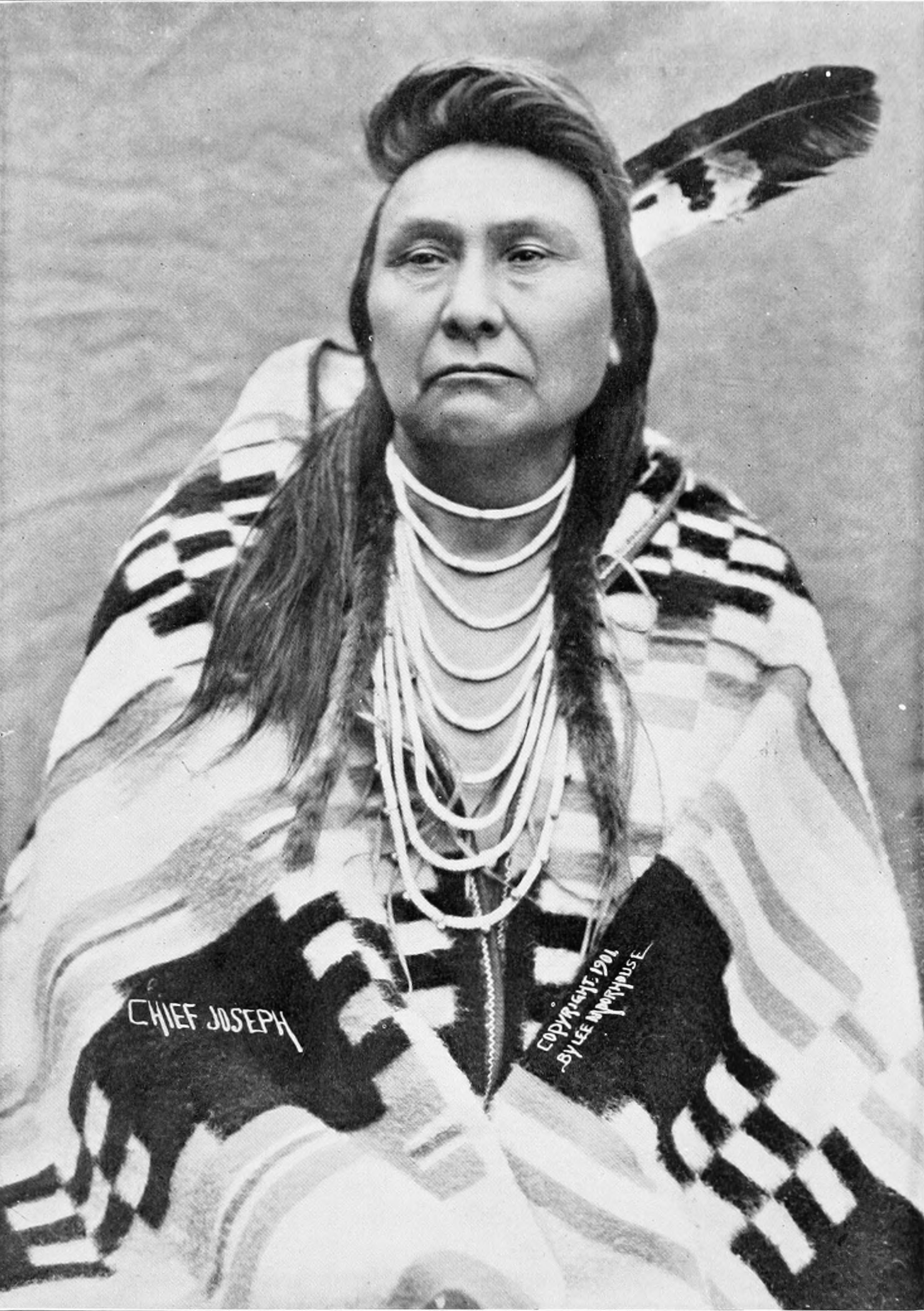

Eligible Native Americans had four years to select their land, but the lands set aside for reservations were not good for farming. In most cases, agreeing to the terms of the Dawes Act was tantamount to agreeing to live off of government handouts forever since the land would never support even a meager living, and so resistance to the reservation policy continued. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Chief Joseph led a group of Nez Perce on a long march to escape to Canada before the army could catch them and escort them to reservations. The quest ultimately failed and he became a symbol of the heroic last push to preserve traditional folkways.

In Montana, the Blackfoot and Crow were forced to leave their tribal lands. In Colorado, the Utes gave up their lands after a brief period of resistance. In Idaho, most of the Nez Perce gave up their lands peacefully, although in an incredible episode, a band of some eight hundred Nez Perce sought to evade government troops and escape into Canada. Chief Joseph, known to his people as “Thunder Traveling to the Loftier Mountain Heights,” hoped to lead the retreat of his people over fifteen hundred miles of mountains and harsh terrain, only to be caught within fifty miles of the Canadian border in late 1877. His speech has remained a poignant and vivid reminder of what the tribe had lost.

“Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before, I have it in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our Chiefs are killed; Looking Glass is dead, Ta Hool Hool Shute is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led on the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets; the little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my Chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.” Chief Joseph, 1877

WOUNDED KNEE

The final episode in the so-called Indian Wars occurred in 1890, at the Massacre of Wounded Knee in South Dakota. On their reservation, the Sioux had begun to perform the Ghost Dance, which told of a Messiah who would deliver the tribe from its hardship, make the Whites disappear and return the world to the way it was before the arrival of the Whites.

Settlers began to worry that the Ghost Dance movement was foretelling an uprising and the militia prepared to round up the Sioux. The tribe, after the death of Sitting Bull, who had been arrested, shot, and killed in 1890, prepared to surrender at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, on December 29, 1890. A detachment of the 7th Cavalry Regiment intercepted Spotted Elk’s band of Miniconjou Lakota and 38 Hunkpapa Lakota and escorted them to Wounded Knee Creek, where they made camp.

On the morning of December 29, the cavalry troops went into the camp to disarm the Lakota. One version of events claims that during the process of disarming the Lakota, a deaf tribesman named Black Coyote was reluctant to give up his rifle, claiming he had paid a lot for it. Simultaneously, an old man was performing a Ghost Dance. Black Coyote’s rifle went off at that point, and the army began shooting at the Native Americans. The disarmed Lakota warriors did their best to fight back. By the time the massacre was over, between 150 and 300 men, women, and children had been killed and 51 were wounded. 25 soldiers also died, and 39 were wounded.

At least 20 soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor at the time, but the event has come to be regarded a massacre on the part of the cavalry, rather than a battle. It does however, mark the last violent conflict on the Great Plains between government troops and Native Americans.

AMERICANIZATION

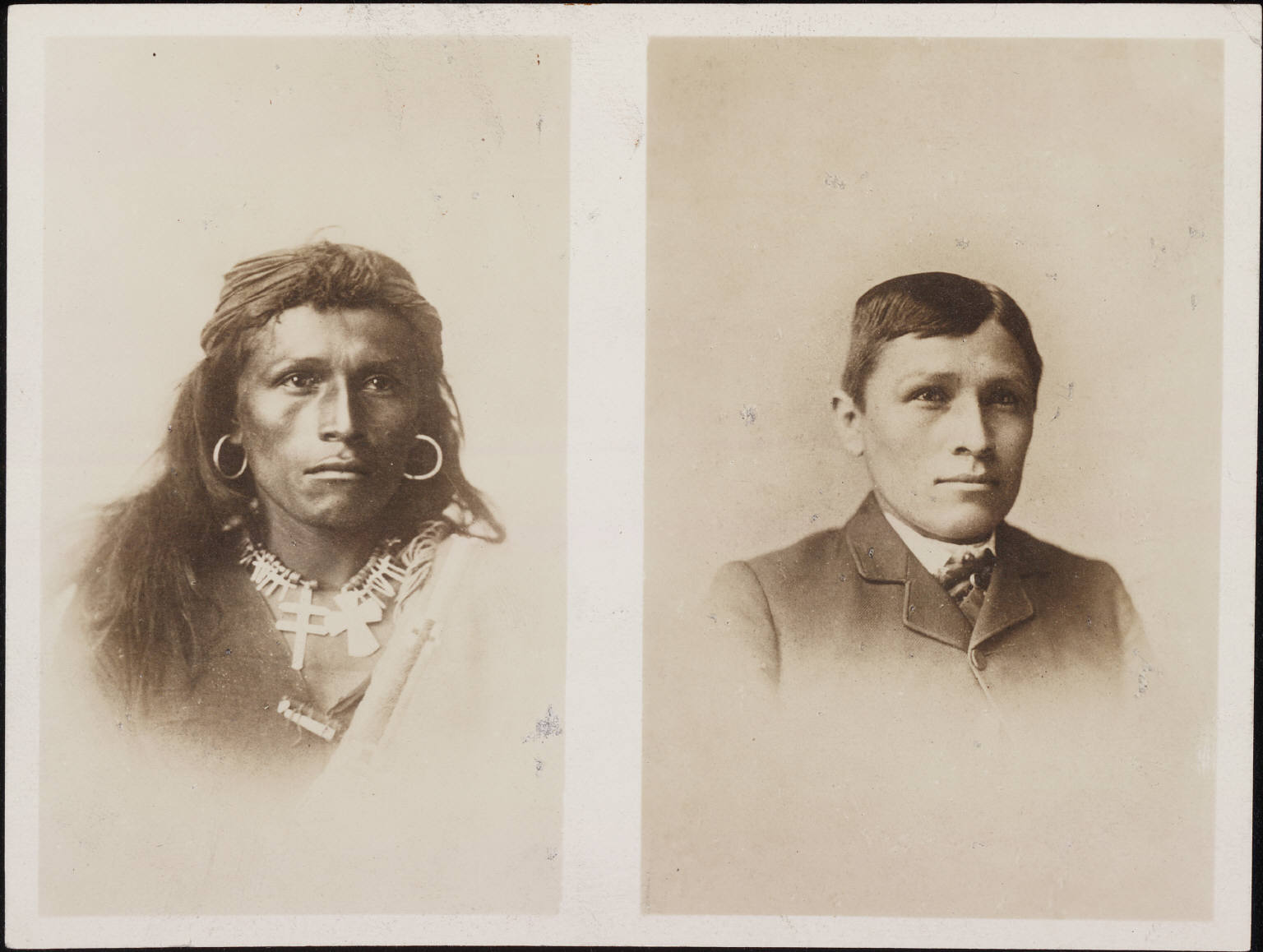

Through the years of the Indian Wars of the 1870s and early 1880s, opinion back East was mixed. There were many who felt, as General Philip Sheridan (appointed in 1867 to pacify the Plains Indians) allegedly said, that “the only good Indian was a dead Indian.” But increasingly, several reformers who would later form the backbone of the Progressive Era had begun to criticize the violence, arguing that the Native Americans should be helped through Americanization to become assimilated into American society.

Individual land ownership, Christian worship, and education for children became the cornerstones of this new, and final, assault on Native American life and culture. Beginning in the 1880s, clergymen, government officials, and social workers all worked to assimilate Natives into American life. The government permitted reformers to remove children from their homes and place them in boarding schools, such as the Carlisle Indian School or the Hampton Institute, where they were taught to abandon their tribal traditions and embrace the tools of American productivity, modesty, and sanctity through total immersion. Such schools not only acculturated Indian boys and girls, but also provided vocational training for males and domestic science classes for females. Adults were targeted by religious reformers, specifically evangelical Protestants as well as a number of Catholics, who sought to convince Native Americans to abandon their language, clothing, and social customs for a White lifestyle. Primary Source: Photographs

Primary Source: Photographs

Tom Torlino, a Navajo who attended the Carlisle Indian School. Before and after photographs such as these were especially popular at the school.

While the concerted effort to assimilate Native Americans into American culture was abandoned officially in the 1930s, integration of Native American tribes and individuals continues to the present day. Non-Native Americans often fail to see that assimilation was never completed.

Since the 1960s, there have been major changes in American society in general, including a broader appreciation for the pluralistic nature of United States and its many ethnic groups, as well as for the special status of Native American nations. More recent legislation to protect Native American religious practices, for instance, points to major changes in government policy. Some tribes have instituted a sort of reverse of the boarding schools of 100 years ago and initiated language immersion schools for children, where a native language is the medium of instruction. For example, the Cherokee Nation instigated a 10-year language preservation plan that involved growing new fluent speakers of the Cherokee language from childhood. The Cherokee Preservation Foundation has invested $3 million into opening schools, training teachers, and developing curricula for language education, as well as initiating community gatherings where the language can be actively used.

Despite efforts to right the wrongs of the past, the nation’s first residents remain its poorest and most oppressed. The United States is home to 3.1 million Native Americans, which accounts for only 0.9% of the entire population. While Native Americans have begun to take more control of their tribal economies, especially through the establishment of casinos, poverty on Reservations is still a major issue. The Census in both 1990 and 2000 found that the poverty rate of Native Americans is 25% and unemployment rates are usually high. For example, the unemployment rate on the Blackfoot Reservation in Montana was 69% at a time when the national unemployment rate was 6.7%. According to the 2000 Census, Native Americans living on reservations have incomes that are less than half of the general population. Alcoholism, mental illness, especially due to fetal alcohol syndrome, and teen suicide all remain problems on America’s Native American reservations.

CONCLUSION

It is hard to look at the history of the Indian Wars and feel anything but shame and sadness for the destruction of lives, cultures, and ecology of the Native American West. Indeed, America’s first citizens are perhaps the ones who lost the most during the course of its history.

So, perhaps the question is easy for us to answer from our perspective in the 21st Century. Of course, the Indian Wars were a tragedy. But, we as historians must remember to look at history through two lenses. Yes, we can view what happened through the perspective we are granted now and judge the past based on our own values. In this way, we can use the Indian Wars, the destruction of the bison, and Americanization as cautionary tales to illustrate messages we wish to tell.

However, we must also consider the past from the perspective of all those who lived through it. Certainly, for some, wasn’t the outcome of the Indian Wars a triumph? Who were these people? Were they evil to have had ideas we judge to be so wrong? What do you think?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The last violent conflicts between Whites and independent Native Americans were in the late 1800s on the Great Plains. Ultimately the army defeated the last of the tribes and forced them to move to reservations where official government policy attempted to destroy Native culture.

As White homesteaders moved into the Great Planes they encountered the last of the free Native American tribes. Some groups moved peacefully. The government promised money and land in the First Treaty of Fort Laramie. In the late 1800s, the army fought a series of wars with the tribes that did not agree to move.

The Sioux were a large confederation of tribes living in what is now the Dakotas and Montana. Violent conflicts between Sioux and White settlers led to the Sand Creek Massacre by the army. Treaties the Natives did sign were often broken. Eventually, the Sioux formed up into a massive fighting force under Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. In 1876, the 7th Cavalry under the command of General Custer lost the Battle of Little Bighorn to this combined Sioux force.

Central to the life of the plains tribes was the buffalo. They used it for its meat, fur, bone, and it was central to their religion as well. Whites understood this and began to slaughter the buffalo on a massive scale. They correctly believed that if there were no buffalo, the Native Americans would not be able to survive and would be forced to move to reservations.

Congress passed the Dawes Act, which sought to make Native Americans live more like White Americans. It divided tribal lands into small portions so that individuals owned property instead of collective ownership by tribes. In most cases, the land set aside for reservations was not good for farming, and these nomads-turned-farmers struggled to survive. They became dependent on the government for supplies of food. Depression and alcoholism developed. The government succeeded in destroying Native cultural practices.

Chief Joseph led his Nez Perce tribe on a desperate trek to cross the border into Canada and escape reservation life. However, he and his people were starving in the cold while pursued by the army and were caught a few miles from the border. His surrender message is famous for its sadness.

The final violent conflict of the Indian Wars happened at Wounded Knee. A new religious movement had swept through Native American societies in the West promising that if they engaged in a Ghost Dance the Whites would disappear and the buffalo would return. A group of mostly women, children and old men engaged in this dance were slaughtered by the army in 1890.

In the following decades, boarding schools were opened where Native Children were taught English and White culture. The Carlisle Indian School was the most famous of these. It was not until the 1940s that this process of forced Americanization ended.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Sioux: Group of related Native American tribes who lived in and around the area that is now North and South Dakota. They mounted some of the last and most fierce resistance to White expansion and the reservation system.

Sitting Bull: Sioux leader during the Indian Wars of the late-1800s. Along with Crazy Horse, he was one of the principle leaders at the Battle of Little Bighorn.

Crazy Horse: Sioux leader during the Indian Wars of the late-1800s. Along with Sitting Bull, he was one of the principle leaders at the Battle of Little Bighorn.

George Custer: Youngest general during the Civil War. He was renowned for his daring cavalry attacks and pursuit of Native Americans in the 1870s. He misjudged the size of the Sioux force at little Bighorn and led his troops into total destruction in 1876.

Chief Joseph: Leader of the Nez Perce in the late-1800s. He led his tribe in a failed attempt to escape across the border into Canada where he believed they would have a better chance of being allowed to continue their traditional way of life. His famous surrender message includes the lines, “My heart is sick and sad” and “I will fight no more forever.”

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Ghost Dance: Religious movement that swept Native American communities in the late-1800s. Led by Wovoka, it promised that if tribes who participated in a special dance, the Whites would disappear and a savior, ancestors and buffalo would return. Whites feared it was a sign up a coming uprising and responded with violence, especially at Wounded Knee.

Americanization: Process of assimilating Native Americans into White society. Well-meaning White leaders believed this would help Native Americans become self-sufficient and opened Indian schools, but it had many negative long-term consequences. The policy was not abandoned until the 1930s.

ANIMALS

Bison/Buffalo: Large land animal that roamed the Great Plains in massive herds and provided the basis for the nomadic lifestyle of the tribes of the plains. They were nearly driven to extinction by Whites who saw their destruction as synonymous with destruction of Native American culture.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Reservations: Areas of land set aside by the federal government for Native American tribes. They are typically located on land that was undesirable for settlement and are more common in the West than the East.

Black Hills: Group of low mountains in South Dakota. They were sacred to some Native American tribes and were the site of an early Sioux reservation until gold was discovered there and the Native Americans were relocated.

Indian Territory: Location of a collection of Native American reservations. The tribes of the Southeast were moved there by Andrew Jackson (including the Cherokee in the Trail of Tears) and tribes of the southern plains such as the Cheyanne, Arapaho and Comanche moved there in the later 1800s. It later became the state of Oklahoma.

Carlisle Indian School: Most famous of the many boarding schools for young Native Americans. These schools were meant to Americanize children by teaching them English and how to participate in White society.

![]()

EVENTS

Sand Creek Massacre: 1864 attack on a Cheyenne village in Colorado by troops under the command of John Chivington. They murdered approximately 100 people, including women and children. Although the army official condemned his actions, the raid served as a model for later attacks and Native American tribes remembered it as a reason not to trust Whites.

Battle of Little Bighorn: 1876 battle between the Sioux nations under the command of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse and the 7th Cavalry under the command of George Custer. It was a rare victory for the Native Americans.

Massacre at Wounded Knee: Last of the violent conflicts between government troops and Native Americans at the end of the 1800s. In December, 1890, the army massacred between 150 and 300 Lakota Sioux who had participated in the Ghost Dance.

![]()

LAWS & TREATIES

First Treaty of Fort Laramie: 1851 agreement between the Federal Government and the tribes of the Great Plains. It set up the reservation system by establishing borders around tribal lands. In return, the government agreed to pay the tribes $50,000/year.

Second Treaty of Fort Laramie: 1868 treaty between the federal government and Sioux in which they agreed to move to the Black Hills area of South Dakota. The treaty was later broken when gold was discovered in the Black Hills.

Treaty of Medicine Lodge: 1867 collection of agreements between the federal government and the tribes of the southern Great Plains that moved them to reservations in exchange for government payouts.

Dawes Act: 1887 law that divided Native American reservations into individually owned plots of land. It was part of the process of assimilation of Native Americans into White culture and accelerated the destruction of traditional native ways of life.