TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

THE RAILROADS

The Pacific Railway Acts were pivotal in helping settlers move west more quickly, as well as move their farm products, and later cattle and mining deposits, back east. The first of many railway initiatives, these acts commissioned the Union Pacific Railroad to build new track west from Omaha, Nebraska, while the Central Pacific Railroad moved east from Sacramento, California. The law provided each company with ownership of all public lands within two hundred feet on either side of the track laid, as well as additional land grants and payment through load bonds, prorated on the difficulty of the terrain it crossed. Because of these provisions, both companies made a significant profit, whether they were crossing hundreds of miles of open plains, or working their way through the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California. As a result the nation’s first transcontinental railroad was completed when the two companies connected their tracks at Promontory Point, Utah, in the spring of 1869. Other tracks, including lines radiating from this original one, subsequently created a network that linked all corners of the nation.

THE FORTS

In addition to legislation designed to facilitate western settlement, the government assumed an active role on the ground, building numerous forts throughout the West to protect and assist settlers during their migration. Forts such as Fort Laramie, built in 1834 in Wyoming and Fort Apache in Arizona served as protection from nearby Native Americans as well as maintained peace between potential warring tribes. Others located throughout Colorado and Wyoming became important trading posts for miners and fur trappers. Those built in Kansas, Nebraska, and the Dakotas served primarily to provide relief for pioneers along the trails west or for farmers during times of drought or related hardships. Forts constructed along the California coastline provided protection in the wake of the Mexican-American War as well as during the American Civil War.

HOMESTEADERS

In the 1800s, as today, it took money to relocate and start a new life. Due to the initial cost of relocation, land, and supplies, as well as months of preparing the soil, planting, and subsequent harvesting before any produce was ready for market, the original wave of western settlers along the Oregon Trail in the 1840s and 1850s consisted of moderately prosperous, White, native-born farming families of the East. But the completion of the first transcontinental railroad and passage of the Homestead Act meant that, by 1870, the possibility of western migration was opened to Americans of more modest means.

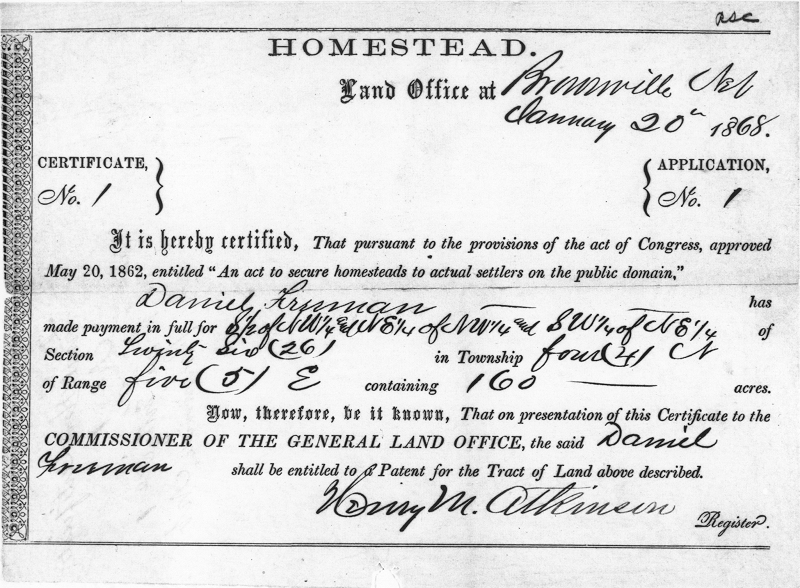

The Homestead Act allowed any head of household, or individual over the age of twenty-one, including unmarried women, to receive a parcel of 160 acres of land for only a nominal filing fee. All that recipients were required to do in exchange was to “improve the land” within a period of five years of taking possession. The standards for improvement were minimal. Owners could clear a few acres, build small houses or barns, or maintain livestock. Under this act, the government transferred over 270 million acres of public domain land to private citizens. Primary Source: Government Document

Primary Source: Government Document

A dead for a homestead in Nebraska from 1868.

What started as a trickle became a steady flow of migration that would last until the end of the century. Nearly 400,000 settlers had made the trek westward by the height of the movement in 1870. The vast majority were men, although families also migrated, despite incredible hardships for women with young children. More recent immigrants also migrated west, with the largest numbers coming from Northern Europe and Canada. Germans, Scandinavians, and Irish were among the most common. These ethnic groups tended to settle close together, creating strong rural communities that mirrored the way of life they had left behind. According to Census Bureau records, the number of Scandinavians living in the United States during the second half of the nineteenth century exploded, from barely 18,000 in 1850 to over 1.1 million in 1900. During that same time period, the German-born population in the United States grew from 584,000 to nearly 2.7 million and the Irish-born population grew from 961,000 to 1.6 million. As they moved westward, several thousand immigrants established homesteads in the Midwest, primarily in Minnesota and Wisconsin, where, as of 1900, over one-third of the population was foreign-born, and in North Dakota, whose immigrant population stood at 45% at the turn of the century.

In addition to a significant European migration westward, several thousand African Americans migrated west following the Civil War, as much to escape the racism and violence of the Old South as to find new economic opportunities. They were known as Exodusters, referencing the biblical flight from Egypt, because they fled the racism of the South, with most of them headed to Kansas from Kentucky, Tennessee, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. Over twenty-five thousand Exodusters arrived in Kansas in 1879–1880 alone. By 1890, over 500,000 African Americans lived west of the Mississippi River. Although the majority of Black migrants became farmers, approximately 12,000 worked as cowboys during the Texas cattle drives. Some joined the army in the wars against the last of the Native American tribes. The Natives equated their black, curly hair with that of the buffalo and they were nicknamed Buffalo Soldiers. Many had served in the Union army in the Civil War and were now organized into six, all black cavalry and infantry units whose primary duties were to protect settlers from Indian attacks during the westward migration, as well as to assist in building the infrastructure required to support western settlement.

As settlers and homesteaders moved westward to improve the land given to them through the Homestead Act, they faced a difficult and often insurmountable challenge. The land was difficult to farm, there were few building materials, and harsh weather, insects, and inexperience led to frequent setbacks. The prohibitive prices charged by the first railroad lines made it expensive to ship crops to market or have goods sent out. Although many farms failed, some survived and grew into large bonanza farms that hired additional labor and were able to benefit enough from economies of scale to grow profitable. Still, small family farms, and the settlers who worked them, were hard-pressed to do more than scrape out a living in an unforgiving environment that comprised arid land, violent weather, and other challenges.

THE LIFE OF THE HOMESTEADER

Of the hundreds of thousands of settlers who moved west, the vast majority were homesteaders. These pioneers, like the Ingalls family of Little House on the Prairie book and television fame, were seeking land and opportunity. Popularly known as sodbusters since they cut the thick prairie grass, these men and women in the Midwest faced a difficult life on the frontier. They settled throughout the land that now makes up the Midwestern states of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Kansas, Nebraska, and the Dakotas. The weather and environment were bleak, and settlers struggled to eke out a living.

A few unseasonably rainy years had led would-be settlers to believe that the great desert was no more, but the region’s typically low rainfall and harsh temperatures made crop cultivation hard. Irrigation was a requirement, but finding water and building adequate systems proved too difficult and expensive for many farmers. It was not until 1902 and the passage of the Newlands Reclamation Act that a system finally existed to set aside funds from the sale of public lands to build dams for subsequent irrigation efforts. Prior to that, farmers across the Great Plains relied primarily on dry-farming techniques to grow corn, wheat, and sorghum, a practice that many continued in later years. A few also began to employ windmill technology to draw water, although both the drilling and construction of windmills became an added expense that few farmers could afford.

The first houses built by western settlers were typically made of mud and sod with thatch roofs, as there was little timber for building. Rain, when it arrived, presented constant problems for these sod houses, with mud falling into food, and vermin, most notably lice, scampering across bedding. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

A sod house, made out of “bricks” of cut sod, the thick prairie grass.

Weather patterns not only left the fields dry, they also brought tornadoes, droughts, blizzards, and insect swarms. Tales of swarms of locusts were commonplace, and the crop-eating insects would at times cover the ground six to twelve inches deep. One frequently quoted Kansas newspaper reported a locust swarm in 1878 during which the insects devoured “everything green, stripping the foliage off the bark and from the tender twigs of the fruit trees, destroying every plant that is good for food or pleasant to the eye, that man has planted.”

Farmers also faced the ever-present threat of debt and farm foreclosure by the banks. While land was essentially free under the Homestead Act, all other farm necessities cost money and were difficult to obtain in the newly settled parts of the country where market economies did not yet fully reach. Horses, livestock, wagons, wells, fencing, seed, and fertilizer were all critical to survival, but often hard to come by as the population remained sparsely settled across vast tracts of land. Railroads charged notoriously high rates for farm equipment and livestock, making it difficult to procure goods or make a profit on anything sent back east. Banks also charged high interest rates, and, in a cycle that replayed itself year after year, farmers would borrow from the bank with the intention of repaying their debt after the harvest. As the number of farmers moving westward increased and harvest yields correspondingly increased, the market price of their produce steadily declined, even as the value of the actual land increased. Each year, hard-working farmers produced ever larger crops, flooding the markets and subsequently driving prices down even further. Although some understood the economics of supply and demand, none could overtly control such forces.

Eventually, the arrival of a more extensive railroad network aided farmers, mostly by bringing much needed supplies such as lumber for construction and new farm machinery. While John Deere sold a steel-faced plow as early as 1838, it was James Oliver’s improvements to the device in the late 1860s that transformed life for homesteaders. His new, less expensive “chilled plow” was better equipped to cut through the shallow grass roots of the Midwestern terrain, as well as withstand damage from rocks just below the surface. Similar advancements in hay mowers, manure spreaders, and threshing machines greatly improved farm production for those who could afford them. Where capital expense became a significant factor, larger commercial farms, known as bonanza farms, began to develop. Farmers in Minnesota, North Dakota, and South Dakota hired migrant farmers to grow wheat on farms in excess of twenty thousand acres each. These large farms were succeeding by the end of the century, but small family farms continued to suffer. Many would-be landowners lured westward by the promise of cheap land became migrant farmers instead, working other peoples’ land for a wage. The frustration of small farmers grew, ultimately leading to the creation of an entirely new political movement. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

A homesteading family in Nebraska in 1866.

Although the West was numerically a male-dominated society, homesteading in particular encouraged the presence of women, families, and a domestic lifestyle, even if such a life was not an easy one. Women faced all the physical hardships that men encountered in terms of weather, illness, and danger, with the added complication of childbirth. Often, there was no doctor or midwife providing assistance, and many women died from treatable complications, as did their newborns. While some women could find employment in the newly settled towns as teachers, cooks, or seamstresses, for the vast majority of women, their work was not in towns for money, but on the farm. As late as 1900, a typical farm wife could expect to devote nine hours per day to chores such as cleaning, sewing, laundering, and preparing food. Two additional hours per day were spent cleaning the barn and chicken coop, milking the cows, caring for the chickens, and tending the family garden. One wife commented in 1879, “[We are] not much better than slaves. It is a weary, monotonous round of cooking and washing and mending and as a result the insane asylum is a third filled with wives of farmers.”

Despite this grim image, the challenges of farm life eventually empowered women to break through some legal and social barriers. Many lived more equitably as partners with their husbands than did their eastern counterparts, helping each other through both hard times and good. If widowed, a wife typically took over responsibility for the farm, a level of management that was very rare back East, where the farm would fall to a son or other male relation. Pioneer women made important decisions and were considered by their husbands to be more equal partners in the success of the homestead, due to the necessity that all members had to work hard and contribute to the farming enterprise for it to succeed.

The cult of domesticity that defined gender roles in the industrial East did not have the same sway in the West. Therefore, it is not surprising that the first states to grant women’s rights, including the right to vote, were those in the Pacific Northwest and Upper Midwest, where women pioneers worked the land side by side with men. Some women seemed to be well suited to the challenges that frontier life presented them. Writing to her Aunt Martha from their homestead in Minnesota in 1873, Mary Carpenter refused to complain about the hardships of farm life, saying, “I try to trust in God’s promises, but we can’t expect him to work miracles nowadays. Nevertheless, all that is expected of us is to do the best we can, and that we shall certainly endeavor to do. Even if we do freeze and starve in the way of duty, it will not be a dishonorable death.”

Although the homesteaders lived far from centers of commerce, they were not entirely isolated. Because of advances in communication and transportation, especially with the expansion of railroad networks, innovative retailers were able to bring the products of the city to the citizens of the prairies and rural South. Aaron Montgomery Ward, Richard Warren Sears and Alvah Curtis Roebuck developed mail order catalog companies that distributed well-known books listing their products – everything from sewing machines, to doll houses, to tractors and event cars and kits to build houses. Until it was surpassed by Walmart in 1989, Sears was the largest retailer in the nation. Not surprisingly, both Sears and Montgomery Ward were based in Chicago, the hub of the rail networks in the Midwest.

While most stories of the West focus on cowboys and gunslingers, the lives of the homesteaders were made famous by Laura Ingalls Wilder. Originally published in the 1930s and 1940s, Ingalls’s book The Little House on the Prairie, and its many sequels have been in print continuously since. The television show, Little House on the Prairie, ran for over a decade and was hugely successful. The books, although fictional, were based on her own childhood as she travelled west with her family via covered wagon, stopping in Kansas, Wisconsin, South Dakota, and beyond. Wilder wrote of her stories, “As you read my stories of long ago I hope you will remember that the things that are truly worthwhile and that will give you happiness are the same now as they were then. Courage and kindness, loyalty, truth, and helpfulness are always the same and always needed.” While Ingalls makes the point that her stories underscore traditional values that remain the same over time, this is not necessarily the only thing that made these books so popular. Perhaps part of their appeal is that they are adventure stories, with wild weather, wild animals, and Native Americans all playing a role.

HISPANICS

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican-American War in 1848, promised American citizenship to the nearly 75,000 Hispanics living in the American Southwest. Approximately 90% accepted the offer and chose to stay in the United States despite their immediate relegation to second-class citizenship status. Relative to the rest of Mexico, these lands were sparsely populated and had been so ever since Mexico had achieved its freedom from Spain in 1821. In fact, New Mexico, not Texas or California, was the center of settlement in the region in the years immediately preceding the war with the United States, containing nearly 50,000 Mexicans. However, those who did settle the area were proud of their heritage and ability to develop ranches of great size and success.

Despite promises made in the treaty, they quickly lost their land to White settlers who simply displaced the rightful landowners, by force when necessary. Repeated efforts at legal redress mostly fell upon deaf ears. In some instances, judges and lawyers would permit the legal cases to proceed through an expensive legal process only to the point where Hispanic landowners who insisted on holding their ground were rendered penniless for their efforts. Much like Chinese immigrants, Hispanic citizens were relegated to the worst-paying jobs under the most terrible working conditions. They worked as peóns (manual laborers similar to slaves), vaqueros (cattle herders), and cartmen (transporting food and supplies) on the cattle ranches that White landowners possessed, or undertook the most hazardous mining tasks.

In a few instances, frustrated Hispanic citizens fought back against the White settlers who dispossessed them of their belongings. In 1889–1890 in New Mexico, several hundred Mexican Americans formed las Gorras Blancas (the White Caps) to try to reclaim their land and intimidate White Americans, preventing further land seizures. White Caps conducted raids of White farms, burning homes, barns, and crops to express their growing anger and frustration. However, their actions never resulted in any fundamental changes. Several White Caps were captured, beaten, and imprisoned, whereas others eventually gave up, fearing harsh reprisals against their families.

Some White Caps adopted a more political strategy, gaining election to local offices throughout New Mexico in the early 1890s, but growing concerns over the potential impact upon the territory’s quest for statehood led several citizens to heighten their repression of the movement. Other laws passed in the United States intended to deprive Mexican Americans of their heritage as much as their lands. Sunday Laws prohibited “noisy amusements” such as bullfights, cockfights, and other cultural gatherings common to Hispanic communities at the time. Greaser Laws permitted the imprisonment of any unemployed Mexican American on charges of vagrancy. Although Hispanic Americans held tightly to their cultural heritage as their remaining form of self-identity, such laws took a toll on the community’s sense of self-worth and pride.

In California and throughout the Southwest, the massive influx of White settlers simply overran the Hispanic populations that had been living and thriving there for generations. Despite being American citizens with full rights, Hispanics found themselves outnumbered, outvoted, and, ultimately, outcast. Corrupt state and local governments favored Whites in land disputes, and mining companies and cattle barons discriminated against them, as with the Chinese workers, in terms of pay and working conditions. In growing urban areas such as Los Angeles, barrios, or clusters of working-class homes, grew more isolated from the White American centers. Hispanic Americans, like the Native Americans and Chinese, suffered the fallout of the White settlers’ relentless push west.

CHINESE

The initial arrival of Chinese immigrants to the United States began as a slow trickle in the 1820s, with barely 650 living in the United States at the end of 1849. However, as gold fever swept the country, Chinese immigrants, too, were attracted to the notion of quick fortunes. By 1852, over 25,000 Chinese immigrants had arrived, and by 1880, over 300,000 Chinese lived in the United States, most in California. While they had dreams of finding gold, many instead found employment building the first transcontinental railroad. Some even traveled as far east as the former cotton plantations of the Old South, which they helped to farm after the Civil War. Several thousand of these immigrants booked their passage to the United States using a credit-ticket, in which their passage was paid in advance by American businessmen to whom the immigrants were then indebted for a period of work, much like the indentured servants of the Colonial Era. Most arrivals were men. Few wives or children ever traveled to the United States. As late as 1890, less than 5% of the Chinese population in the United States was female. Regardless of gender, few Chinese immigrants intended to stay permanently although many were reluctantly forced to do so, as they lacked the financial resources to return home.

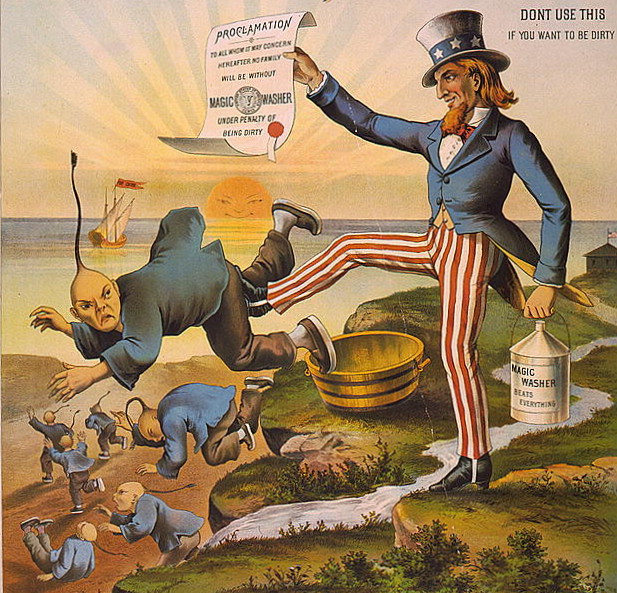

Prohibited by law since 1790 from obtaining citizenship through naturalization, Chinese immigrants faced harsh discrimination and violence from White settlers in the West. Despite hardships like the special tax that Chinese miners had to pay to take part in the Gold Rush, or their subsequent forced relocation into Chinese districts, these immigrants continued to arrive in the United States seeking a better life for the families they left behind. Only when the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 forbade further immigration from China for a ten-year period did the flow stop. Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

Uncle Sam kicks Chinese immigrants out of the United States. Such attitudes were widespread among the White population in California and the nation in general.

The Chinese community banded together in an effort to create social and cultural centers in cities such as San Francisco. There, they sought to provide services ranging from social aid to education, places of worship, health facilities, and more to their fellow Chinese immigrants through the creation of benevolent societies. Only Native Americans suffered greater discrimination and racial violence, legally sanctioned by the federal government, than did Chinese immigrants at this juncture in American history. As Chinese workers began competing with White Americans for jobs in California cities, the latter began a system of built in discrimination. In the 1870s, white Americans formed anti-coolie clubs. Coolie was a racial slur directed towards people of any Asian descent, through which they organized boycotts of Chinese produced products and lobbied for anti-Chinese laws. Some protests turned violent, as in 1885 in Rock Springs, Wyoming, where tensions between White and Chinese immigrant miners erupted in a riot, resulting in over two dozen Chinese immigrants being murdered and many more injured.

Slowly, racism and discrimination became law, and the history of Chinese immigrants to the United States remained largely one of deprivation and hardship well into the twentieth century.

CONCLUSION

Real people settled the West. Miners, homesteaders, Chinese railroad laborers, children growing up on the prairie – they were all real people. But now, 100 years later, they have become something more than that. The Founding Fathers are glorified, but they are still real people to us.

Not so with the people of the West. For us, the cowboys, outlaws, miners and brave pioneers who cut the sod and tamed the West have been divorced from their true selves. Television, dime novels, and Hollywood have made them into something else entirely. They are now part of the American myth. They define us. We are them. We seek to embody their ethos, their values, the traits we think made them successful, and live our lives as if we were them.

What do you think? How have the real people, and mythologized people of the West shaped our national identity?

And perhaps more importantly, how have the stories of those people, shaped your own identity?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: There were many groups of people who defined the character of the West. Some of these people have become mythologized.

Railroads eventually stretched across the West. The first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869. The western side was built mostly by Chinese immigrants. Other railroads soon followed.

The army built forts in the West. These served as trading hubs and stopping points for pioneers crossing the plains. The Homestead Act gave inexpensive land to anyone who could stay and survive as farmers in the West. This last group of people to move West were the ones who stayed and truly settled the West, because they came as families. Some were Exodusters, former slaves who struck out to make a new life on the prairie. Life on the plains was hard, and some didn’t make it. Over time, farmers sold their land to bonanza farms and farming started to consolidate the same way industry was consolidating in the East. With the expansion of railroads, homesteaders could buy things from the East. Mail order catalogue companies such as Sears, grew up to provide for them.

Hispanics who found themselves in the United States after the Mexican-American War often lost their land to Whites. Some fought back, but they generally lost out as Whites pushed west.

Chinese immigrants who arrived in California for the gold rush, also lost out. Whites did not want to share claims to land and Chinese immigrants ended up working in industries that supported the miners, or on the railroads. The Chinese Exclusion Act ended all immigration from China in 1882.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Mountain Men: The White explorers who travelled throughout the Rocky Mountains and West in the early and mid-1800s. They were essential in the early years of westward expansion because they discovered passes, rivers, and later served as guides for miners, the army, and pioneer who settled the region.

John Colter: First of the mountain men. He was a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and was the first White person to see Yellowstone.

Jim Beckwourth: Famous African American mountain man. He lived with the Crow tribe and discovered a pass through the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California.

Jim Bridger: Mountain man who was the first to see the Great Salt Lake in Utah. He was well known as a story teller.

Jedediah Smith: Important mountain man who explored much of California and Nevada. He was a successful businessman and a partner in the Rocky Mountain Fur Company.

Kit Carson: Prototypical mountain man. He helped Fremont explore California, married into two different Native American tribes and was a national hero.

Prospectors: People who search for gold or other precious metals.

Forty-Niners: Nickname for the prospectors who travelled to California during the Gold Rush. Their name is derived from the first year of the migration of such miners.

Levi Strauss: Co-founder of the Levi’s company and inventor of jeans. He had gone to California to sell tents to Forty-Niners but found that he could use the canvas he brought to create durable pants that were in greater demand.

Joseph G. McCoy: Businessman who purchased cattle in Kansas and shipped it to consumers in the East. He helped make the cattle drives and Americans’ love for beef possible.

Gunslingers: Nickname for the lawmen and criminals of the West, based on the fact that many carried handguns and some were legendary for their supposed abilities with these pistols.

Wyatt Earp: Famous lawman of the Wild West. He and his brothers were participants in the Showdown at the OK Corral in Tombstone, Arizona in 1881.

Outlaws: Criminals of the Wild West. Many had been Confederate soldiers during the Civil War who continued fighting in the 1870s and 1880s. Jesse James, Billy the Kid and Butch Cassidy are famous examples.

James-Younger Gang: Gang of famous outlaws of the Wild West. They had been confederate soldiers during the Civil War from Missouri and later robbed banks, trains and stagecoaches in many states. Their failed raid on a bank in Northfield, Minnesota proved to be their undoing.

Jesse James: Famous outlaw who led the James-Younger Gang. He was eventually killed by a member of his own gang.

Billy the Kid: Famous young outlaw in New Mexico and Arizona who was wanted for multiple murders. He was killed by sheriffs when he was only 21.

Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch: One of many outlaw gangs in Wyoming in the 1890s. They robbed trains the gang was made up of men with colorful nicknames who epitomized the Wild West.

Exodusters: Nickname for former slaves who moved west as pioneers after the Civil War.

Buffalo Soldiers: Nickname for African American soldiers who participated in the Indian Wars of the late 1800s.

Sodbusters: Nickname for the pioneers who settled in the Great Plains and struggled with harsh weather to farm the thick soil.

Laura Ingalls Wilder: Pioneer writer of autobiographical stories of life on the Frontier. Her many books are still hugely popular.

Peons: Name for the manual laborers in the Southwest. Such jobs were some of the only positions available to Hispanics after the region was absorbed into the United States after the Mexican-American War.

Vaqueros: Spanish name for cowboys. Many of the cowboys of the West were Hispanic.

Gorras Blancas: Group of Hispanics who raided White-owned farms in New Mexico around 1890. Their brief period of violent resistance was born of frustration about the treatment of Hispanics as Whites moved into and took over power in the region.

Anti-Coolie Clubs: Nativist organizations formed by White Americans in the 1870s in California to promote anti-Chinese policies. Some of these groups also carried out violent attacks on Chinese communities.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Wild West: A term that refers to the West during the early years of settlement when there was little formal government, and few women.

Frontier Myth: Romanticized idea of what the West was like before it was fully settled. This idea contains such concepts as lawmen who stood up for justice against evil outlaws, noble cowboys braving the elements to drive cattle north, and independent miners struggling against nature to win their reward. Values such as independence, justice, and freedom are part of this idea which is still celebrated in America today.

BUSINESS

Union Pacific Railroad: Company that built the Transcontinental Railroad from Iowa to Utah.

Central Pacific Railroad: Company that built the Transcontinental Railroad from California to Utah.

Mail Order Catalog: A book offering items for purchase that became popular in the late-1800s. They were especially aimed at rural customers and were made possible by the development of the railroad. Sears was one of the first to capitalize on this opportunity.

SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY

Panning: A process of searching for gold by sifting through the gravel at the bottom of a stream.

Longhorn: A type of cow descended from the cattle released by Spanish explorers in Texas. The famous cattle drives of the 1860s and 1870s involved driving these cows north to railheads. They are symbol associated with Texas.

Barbed Wire: Invention that allowed ranchers and farmers to quickly build miles of fences that cows would not penetrate, thus bringing an end to the days of the cattle drives.

Transcontinental Railroad: First railroad connecting the East with California. It was built by two companies, the Union Pacific in the East and the Central Pacific in the West. The two tracks eventually met at Promontory Point in Utah in 1869.

Little House on the Prairie: First of the many autobiographical books by Laura Ingalls Wilder about her family’s life as pioneers on the Great Plains in the late-1800s.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Sutter’s Mill: Location gold was discovered in California in 1848.

Comstock Lode: Major discovery of gold in Nevada. Found in 1859, it was eventually mined with hundreds of tunnels dug deep into the mountain.

Ghost Town: A town that was abandoned in the West, leaving behind homes, shops, etc., usually when a mine ran out and residents moved on to other prospective digs.

Chisholm Trail: Famous route of the cattle drives of the 1860s and 1870s. It runs from Texas, through Oklahoma to Kansas.

Cow Town: Nickname for any one of the towns at the ends of the railroad lines in Kansas that were the destinations of the cattle drives of the 1860s and 1870s. Abilene, Wichita and Dodge City were famous examples.

Promontory Point, Utah: Spot where the tracks being laid by the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads finally met in 1869 and the golden spike was driven in, thus completing the first transcontinental railroad.

Fort Laramie: Important army fort and trading post along the Oregon Trail in Wyoming.

Bonanza Farm: Large commercial farms made up of many smaller homesteads in the Great Plains that developed in the late-1800s. They developed as individuals realized that it was inefficient to try to raise grain in small amounts and sold out to wealthier neighbors. This process mirrored the industrial consolidation happening in the East at the same time.

Barrios: Hispanic neighborhoods in the growing cities of the West. They developed as White migrants took over political and economic power in the late-1800s and early-1900s.

![]()

EVENTS

Rendezvous: Annual meetings of mountain men held between 1820 and 1840 where furs were traded. They were important economic and social events.

California Gold Rush: Major migration of people to California beginning in 1849 to search for gold.

Cattle Drive: Movement of longhorn cows rounded up in Texas and driven by cowboys north to railheads in Kansas. They were common in only the 1860s and 1870s before the extension of railroads further west, but are emblematic of the West in general.

Showdown at High Noon: Legendary event in which two men faced off to settle a dispute by dueling in the days of the Wild West. Such events were actually rare but are an important part of the myth of the West and feature in many stories and movies.

Showdown at the OK Corral: An actual duel that happened between Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday and other lawmen and outlaws in 1881 in the town of Tombstone, Arizona. It is the most famous gunfight of the Wild West.

![]()

LAWS

Pacific Railway Acts: Series of laws passed in 1862 that granted public land to railway companies in order to construct the Transcontinental Railroad. It was one of many times the federal government official supported the railroad industry in order to spur development.

Homestead Act: 1862 law that granted pioneers land in the West if they could survive and farm it. It was an important driver of migration from the East as well as inspiration for foreign immigrates seeking a better life as farmers in America.

Sunday Laws: A series of laws that were passed by Whites in New Mexico in the 1890s aimed at restricting Hispanic culture. They banned such practices as bullfights.

Greaser Laws: Laws passed in New Mexico in the 1890s that allowed White authorities to imprison unemployed Hispanics.

Chinese Exclusion Act: Law passed in 1882 that ended all immigration from China and prevented any Chinese person already in the United States from becoming a citizen.