TRANSLATE

[google-translator]

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

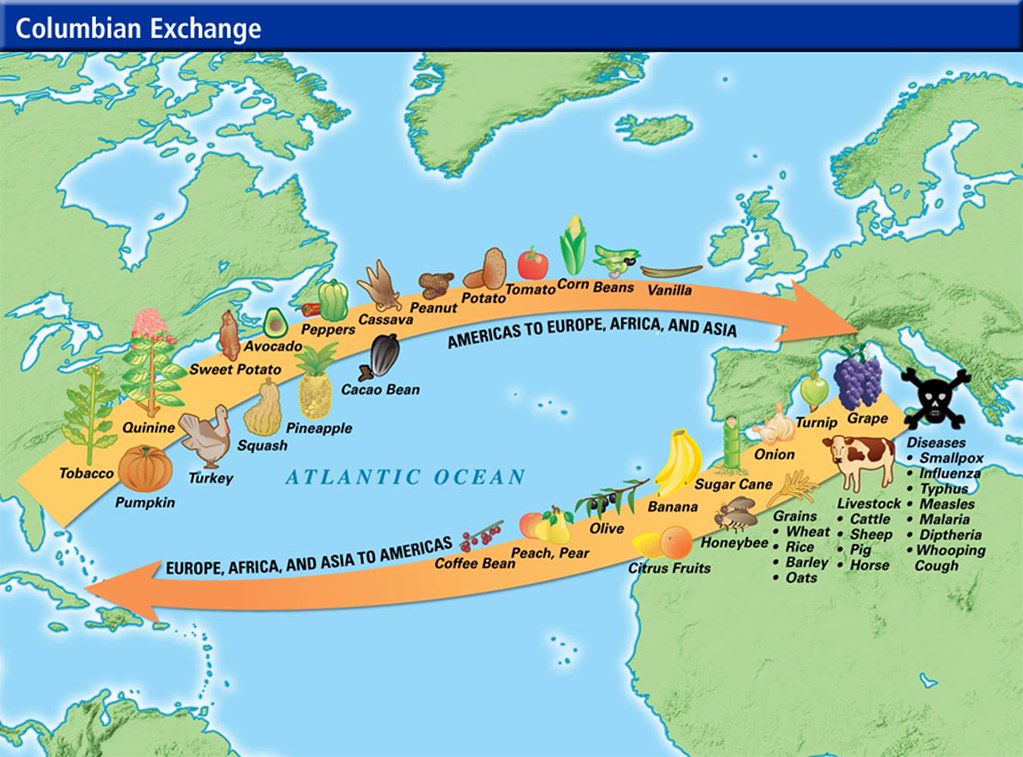

The Columbian Exchange is the name historians have given to the movement of people, plants, animals, microbes and ideas between the Old World and New after the landfall of Columbus in 1492. Although the Europeans did not intentionally remake the world, their journeys had an enormous impact.

New crops introduced to Europe and Africa from the Americas such as potatoes and corn resulted in an explosion in the population as agriculture could feed more people. Conversely, Old World diseases such as smallpox decimated Native American populations. Horses, an Old World animal were brought to America, escaped, were captured by Native Americans, and eventually formed the basis for the nomadic societies of the Great Plains.

Gold from the New World enriched colonial nations, but eventually led to inflation and remade the economic systems and brought about an end to feudalism.

Religions spread, as did language, art, music and literature. So did slavery.

The changes brought about by the Columbian Exchange were both positive and negative, but what do you think? Was the Columbian Exchange a net benefit for humanity?

FLORA

As Europeans traversed the Atlantic, they brought with them plants, animals, and diseases that changed lives and landscapes on both sides of the ocean. These two-way exchanges between the Americas and Europe/Africa are known collectively as the Columbian Exchange.

Of all the commodities in the Atlantic World, sugar proved to be the most important. Indeed, sugar carried the same economic importance as oil does today. European rivals raced to create sugar plantations in the Americas and fought wars for control of some of the best sugar production areas. Although refined sugar was available in the Old World, Europe’s harsher climate made sugarcane difficult to grow, and it was not plentiful. Columbus brought sugar to Hispaniola in 1493, and the new crop was growing there by the end of the 1490s. By the first decades of the 1500s, the Spanish were building sugar mills on the island. Over the next century of colonization, the Caribbean islands and most other tropical areas became centers of sugar production.

Though of secondary importance to sugar, tobacco achieved great value for Europeans as a cash crop as well. Native peoples had been growing it for medicinal and ritual purposes for centuries before European contact, smoking it in pipes or powdering it to use as snuff. They believed tobacco could improve concentration and enhance wisdom. To some, its use meant achieving an entranced, altered, or divine state; entering a spiritual place.

Tobacco was unknown in Europe before 1492, and it carried a negative stigma at first. The early Spanish explorers considered natives’ use of tobacco to be proof of their savagery and, because of the fire and smoke produced in the consumption of tobacco, evidence of the Devil’s sway in the New World. Gradually, however, European colonists became accustomed to and even took up the habit of smoking, and they brought it across the Atlantic. As did the Natives, Europeans ascribed medicinal properties to tobacco, claiming that it could cure headaches and skin irritations. Even so, Europeans did not import tobacco in great quantities until the 1590s. At that time, it became the first truly global commodity; English, French, Dutch, Spanish, and Portuguese colonists all grew it for the world market. Maya illustration of people eating and drinking chocolate

Maya illustration of people eating and drinking chocolate

Native peoples also introduced Europeans to chocolate, made from cacao seeds and used by the Aztec in Mesoamerica as currency. Mesoamerican Indians consumed unsweetened chocolate in a drink with chili peppers, vanilla, and a spice called achiote. This chocolate drink, called xocolatl by the Aztec, was part of ritual ceremonies like marriage and an everyday item for those who could afford it. Chocolate contains theobromine, a stimulant, which may be why native people believed it brought them closer to the sacred world.

Spaniards in the New World considered drinking chocolate a vile practice. One even called chocolate “the Devil’s vomit.” In time, however, they introduced the beverage to Spain. At first, chocolate was available only in the Spanish court, where the elite mixed it with sugar and other spices. Later, as its availability spread, chocolate gained a reputation as a love potion.

The crossing of the Atlantic by plants like cacao and tobacco illustrates the ways in which the discovery of the New World changed the habits and behaviors of Europeans. Europeans changed the New World in turn, not least by bringing Old World animals to the Americas. On his second voyage, Christopher Columbus brought pigs, horses, cows, and chickens to the islands of the Caribbean. Later explorers followed suit, introducing new animals or reintroducing ones that had died out (like horses). With less vulnerability to disease, these animals often fared better than humans in their new home, thriving both in the wild and in domestication.

FAUNA

Europeans encountered New World animals as well. Because European Christians understood the world as a place of warfare between God and Satan, many believed the Americas, which lacked Christianity, were home to the Devil and his minions. The exotic, sometimes bizarre, appearances and habits of animals in the Americas that were previously unknown to Europeans, such as manatees, sloths, and poisonous snakes, confirmed this association. Over time, however, they began to rely more on observation of the natural world than solely on scripture. This shift from seeing the Bible as the source of all received wisdom to trusting observation or empiricism is one of the major outcomes of the era of early globalization.

Initially, at least, the Columbian exchange of animals largely went through one route, from Europe to the New World, as the Eurasian regions had domesticated many more animals. Horses, donkeys, mules, pigs, cattle, sheep, goats, chickens, large dogs, cats and bees were rapidly adopted by native peoples for transport, food, and other uses. One of the first European exports to the Americas, the horse, changed the lives of many Native American tribes in the mountains. They shifted to a nomadic lifestyle, as opposed to agriculture, based on hunting bison on horseback and moved down to the Great Plains. The existing Plains tribes expanded their territories with horses, and the animals were considered so valuable that horse herds became a measure of wealth.

Still, the effects of the introduction of European livestock on the environments and peoples of the New World were not always positive. In the Caribbean, the proliferation of European animals had large effects on native fauna and undergrowth and damaged conucos, plots managed by indigenous peoples for subsistence.

Often overlooked, even small animals had enormous effects on the Americas. Earthworms, for example, were brought in the soil of plants and transformed American forests. Earthworms are decomposers and can significantly change the pH of soil, resulting in changes to the native plants that can survive. As earthworms spread, whole landscapes changed. A time traveler might not recognize the forests of pre-Columbian America, nor realize that the forests we know today were so affected by this seemingly insignificant part of the Columbian Exchange.

MICROBES

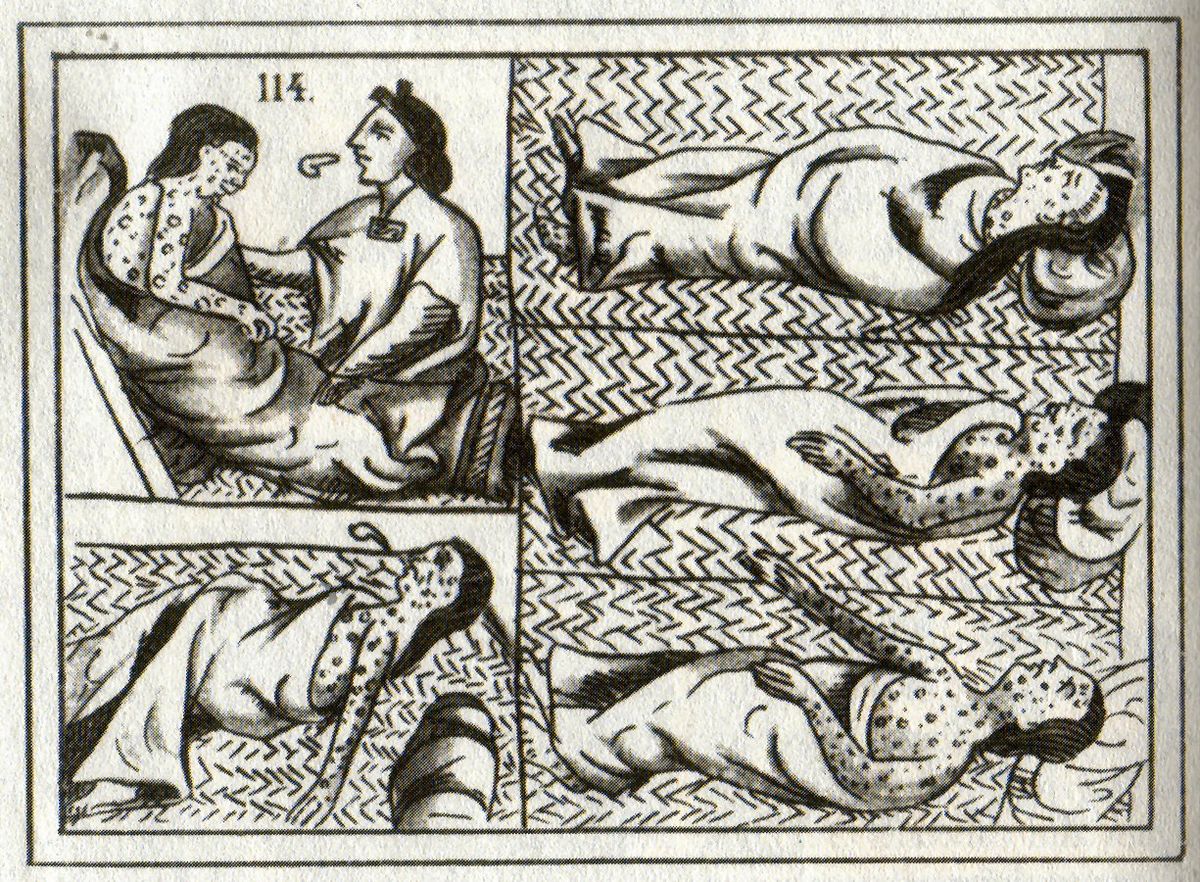

Travelers between the Americas, Africa, and Europe also included microbes: silent, invisible life forms that had profound and devastating consequences. Native peoples had no immunity to diseases from across the Atlantic, to which they had never been exposed. European explorers unwittingly brought with them chickenpox, measles, mumps, and smallpox, which ravaged native peoples despite their attempts to treat the diseases, decimating some populations and wholly destroying others. Of all the diseases brought from the Old World, smallpox was by far the greatest killer. Some researchers estimate that 90% of Native Americans died from this disease. A page from an Aztec codex depicting Native people dying from Smallpox, a disease that that was unknown in the Americas before the Columbian Exchange

A page from an Aztec codex depicting Native people dying from Smallpox, a disease that that was unknown in the Americas before the Columbian Exchange

In eastern North America, some native peoples interpreted death from disease as a hostile act. Some groups, including the Iroquois, engaged in raids or “mourning wars,” taking enemy prisoners in order to assuage their grief and replace the departed. In a special ritual, the prisoners were “requickened”—assigned the identity of a dead person—and adopted by the bereaved family to take the place of their dead. As the toll from disease rose, mourning wars intensified and expanded.

PEOPLE

A debate is currently raging among historians between those who argue for what is known as the “large count,” and those who espouse a “low count” of the pre-Columbian population of the Americas. Since evidence is poor, historians must do their best interpretations of the little there is to estimate how many Native Americans there actually were when Columbus arrived. This is not a purely academic question. Those who argue the high count side, are by extension arguing that many millions more Native Americans perished from disease than those who favor a low count. This raises many important ethical questions and questions identity, power, and justice that spill over into modern politics, especially in some countries where divisions between the native and non-native populations are pronounced.

We do know many Native American societies were swept with devastating diseases even when Europeans were not there to witness it. For example, the Spanish travelled up the Mississippi River in the early 1500s and reported seeing many villages. Roughly 100 years later when French explorers traversed the same route, they reported none. It does not make sense that thousands of people would have abandoned their existence along an important waterway. What does make sense is that their lives were upended as microbes left behind by those first Spanish explorers wreaked havoc.

Countless people from the Old World eventually travelled to the Americas, but very few went in the other direction. Along with Europeans who came by choice, millions of Africans were brought to the New World as slaves.

The Spanish were the first Europeans to use enslaved Africans in the New World on islands such as Cuba and Hispaniola. The alarming death rate experienced by the indigenous population had spurred the first royal Spanish laws protecting them, and consequently, the first enslaved Africans arrived in Hispaniola in 1501.

Increasing penetration into the Americas by the Portuguese created more demand for labor in Brazil—primarily for farming and mining. Slave-based economies quickly spread to the Caribbean and the southern portion of what is today the United States. There, Dutch traders brought the first enslaved Africans in 1619. These areas all developed an insatiable demand for slaves.

As European nations grew more powerful, especially Portugal, Spain, France, Great Britain, and the Netherlands, they began vying for control of the African slave trade, with little effect on local African and Arab trading. Great Britain’s existing colonies in the Lesser Antilles, and its effective naval control of the Mid-Atlantic, forced other countries to abandon their enterprises due to inefficiency in cost. The English crown provided a charter giving the Royal African Company monopoly over the African slave routes until 1712.

The Atlantic slave trade peaked in the late 18th century, when the largest number of slaves was captured on raiding expeditions into the interior of West Africa. The expansion of European colonial powers to the New World increased the demand for slaves and made the slave trade much more lucrative to many West African powers, leading to the establishment of a number of West African empires that thrived on the slave trade. A contemporary image of the sugar-growing region of Portuguese Brazil

A contemporary image of the sugar-growing region of Portuguese Brazil

CONCLUSION

It is easy to point out the negative effects of the meeting of the Old and New Worlds, but we should not overlook the enormous positive changes that have resulted. It may seem like a small thing, but consider this: without the Columbian Exchange, we would not have pizza – flour for the dough is from the Old World and tomatoes are from the New.

When it comes to the Columbian Exchange, blame seems like a frivolous exercise. The Europeans whose actions brought on the exchange had no idea what they were unleashing. They did not have any understanding of invasive species and had not invented science, let alone discovered microbes or come to understand the true causes of disease.

So, a more appropriate question is to consider the effects of the exchange in terms of the course of world history. It certainly resulted in irreversible change. But what do you think?

Was the Columbian Exchange a net benefit for humanity? A simple graphic shows some of the wide variety of plants, animals, and microbes shared between the Old World and New World as a result of the Columbian Exchange.

A simple graphic shows some of the wide variety of plants, animals, and microbes shared between the Old World and New World as a result of the Columbian Exchange.

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The conquest of the Americans led to a major change in world history as plants, animals, microbes, people and ideas were exchanged.

The Columbian Exchange is the name historians give to all the plants, animals, diseases, people and ideas shared between the Old World of Europe, Asia and Africa and the New World of the Americas after first contact was made by Christopher Columbus in 1492. Since this exchange was enormously influential, 1492 is an important turning point in world history.

Sugar and rice were brought from the Old World to the New. Tobacco, potatoes, tomatoes and chocolate were New World crops brought to the Old World.

Domesticated animals such as horses, pigs, cows, sheep, goats and chickens were brought to America. Europeans also brought earthworms, which transformed the forests and fields of the Americas.

Most significantly for Native Americans was the exchange of diseases. Smallpox came from Europe and devastated Native American populations. It is estimated that 90% of Native Americans died from introduced diseases.

People were also part of the Columbian Exchange. Some came by choice, such as the Spanish, French and eventually the British colonists. Others did not come by choice, such as the African slaves. Once in America, some remained racially segregated whereas in other colonies they intermarried. The Spanish developed a caste system based on the purity of one’s heritage, with those of pure Spanish ancestry at the top, and those of pure African ancestry at the bottom.

VOCABULARY

![]()

KEY CONCEPTS

Columbian Exchange: Name given to the mixing of animals, plants, microbes, people and ideas between the Old World and New World after Columbus’s first voyage in 1492.