JUMP TO

TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

It is a common joke that politicians lie, but most of the time we expect our leaders to tell us the truth about what is happening and what they are trying to do. For most of our history, Americans believed what their presidents told them. That is not the case today. Now, we usually don’t trust what they say. And people who report the watch for lies. Some newspapers even keep a list of each time a president tells even a small lie. The Washington Post’s famous fact checkers give Pinocchios to leaders the way reviewers give stars to movies.

How did this change happen? How is it that we came to be so distrusting? And also, does that include other leaders, such as CEOs, generals, superintendents, principals, or even teachers?

This change happened during the 1970s. A simple chart showing how many people trust the president over time drops during those years and learning about what happened back then can give us a good idea as to why this change happened. In the 1970s, we learned that many presidents had been lying about the Vietnam War, a president quit after trying to hide crimes, and all three presidents during the 1970s all were unable to help people who were losing their jobs.

That brings us to our question. The 1970s showed that sometimes our presidents lie, or at least sometimes cannot achieve the goals we wish they could. But does that mean we can’t trust our leaders, or just that we should expect them to earn our trust?

What do you think? Can we trust our country’s leaders?

THE PENTAGON PAPERS

In 1967, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara asked a special group of writers to create an “encyclopedic history of the Vietnam War.” McNamara thought that a good history of what happened in Vietnam might help other presidents avoid making the same mistakes. But McNamara did not tell anyone else about his project.

Instead of using historians that already worked for the Defense Department, McNamara gave the job to his close aides. Thirty-six people worked on the project. To keep their work a secret, they mostly used existing files in the Office of the Secretary of Defense and did not do any interviews. The study was 3,000 pages long and had 4,000 pages of original government documents. It was labeled “Top Secret.”

But the report did not stay a secret. One of the writers, Daniel Ellsberg, was against the war, and he and his friend Anthony Russo made copies of the study in October 1969. They planned to give those copies to people in the news. Ellsberg thought the report showed “unconstitutional behavior” by many presidents as they had lied about what was happening in Vietnam.

In February 1971, Ellsberg gave New York Times reporter Neil Sheehan large numbers of his copies. The lawyers for The New York Times could not agree about printing the report. Some thought it was a bad idea. But in the end, they decided that newspapers had a First Amendment right to print information that was important and would help people know what their government was doing.

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

A 1971 cartoon by Don Wright panning the military and government for their deception during the Vietnam War.

The New York Times began printing the documents on June 13, 1971, in a series titled “Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces Three Decades of Growing US Involvement.” Later, people called it The Pentagon Papers for short.

The Pentagon Papers showed that four presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson had not told the truth about the war in Vietnam. For example, Eisenhower tried to stop the Geneva Accords because communists might have won a free election. Kennedy’s team knew about the plan to kill South Vietnamese leader Ngo Dinh Diem. President Johnson had decided to send more soldiers to Vietnam even though he promised he would not and planned to bomb North Vietnam even before he won the election in 1964. During the campaign, President Johnson had said bombing the North was a bad idea and said that his opponent Barry Goldwater that wanted to bomb North Vietnam.

When he learned about the report, President Nixon thought he did not need to do anything. The report made Kennedy and Johnson look bad, not him. But Henry Kissinger told the president that not trying to stop the New York Times from printing the Pentagon Papers might make other people think giving government secrets to newspapers was ok, and they might tell the newspapers something embarrassing about Nixon. Nixon’s lawyers asked the New York Times to stop printing the papers, but the newspaper’s leaders said no. Then, the Attorney General and Nixon asked a judge to order the Times to stop printing. The newspaper appealed the order, and the case New York Times Co. v. United States went up to the Supreme Court.

Then the Washington Post, which had also gotten parts of the report from Ellsberg, started printing its own articles about the Pentagon Papers. Again, Nixon’s lawyers tried to stop the newspapers in court. In the end, the Supreme Court decided to join the Washington Post case with the New York Times case. It was going to be an important fight between the press and the government about power and freedom.

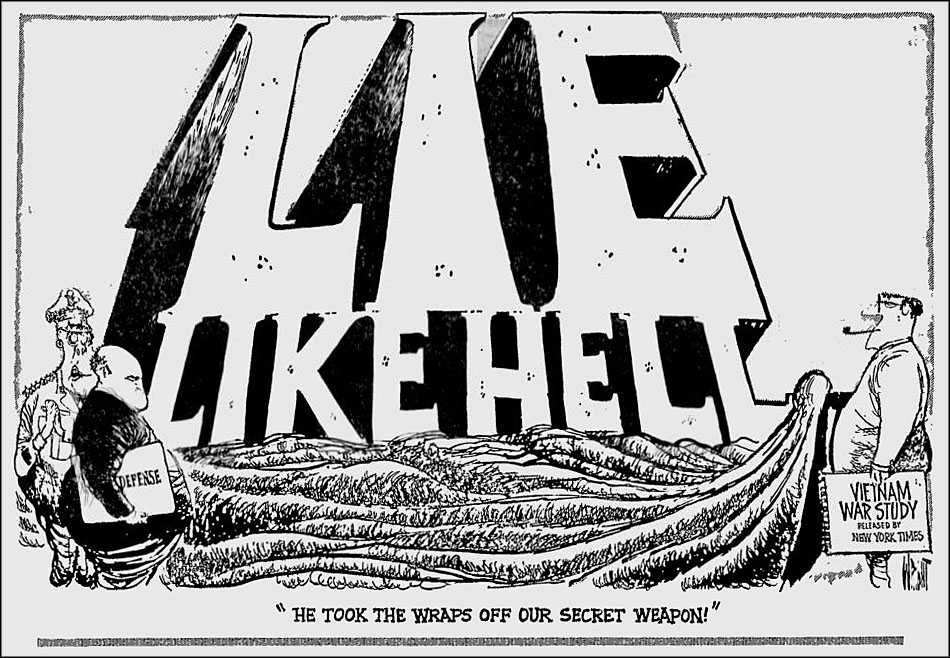

Primary Source: Magazine Cover

Primary Source: Magazine Cover

Many news sources published stories about the Pentagon Papers, including Time Magazine.

On June 30, 1971, the Supreme Court decided, 6-3, that Nixon and the government did not show that the country would be hurt if the newspapers printed the Pentagon Papers. The nine justices each had their own ideas and reasons, but they all agreed on one basic idea: people in the news are important because they protect us from politicians who lie, and we need a free press to help keep us free from bad leaders.

The case was a big win for newspapers, and the media in general. Even today, the New York Times Co. v. United States case protects the right of the press to report what government leaders are doing, even if those leaders don’t want the public to know.

Ellsberg turned himself in and admitted that he had given the report to the newspapers saying he thought it was important for him to show how leaders had been lying and that he knew was hurting people. He was put on trial for stealing and holding secret documents. But Nixon’s lawyers messed up the case. Scared that other people might give secrets to the newspapers, Nixon’s team, called the Plumbers, had tried to embarrass Ellsberg. They had broken into the office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist to look for something that would make him look bad.

Judge William Matthew Byrne, Jr. threw out all the charges against Ellsberg and his partner Russo after he found out what the Plumbers had done. Ellsberg and Russo were set free, and the public began to think that maybe Nixon told as many lies as the presidents before him.

In 2011, the National Archives and Records Administration made the Pentagon Papers public. Today, anyone can read the Pentagon Papers online.

NIXON’S REELECTION

After their disorganized and violent meeting in Chicago in 1968, the Democratic Party changed the rules for its presidential candidate. The new rules gave delegates for each candidate based on how many votes a candidate got in each state primary election. This meant that a candidate who did not win any primaries would not be able to be the party’s nominee, which Hubert Humphrey had done in Chicago.

The new rules gave greater power to voters and took power away from party leaders. This change made America’s government more democratic. That is, the people would have more control over who the president would be. In 1972, Shirley Chisholm, a member of the House of Representatives from New York became the first African American and first woman to win support from the Democratic or Republican Party when she won 156 delegates.

In the end, Democrats picked George McGovern, who was against the Vietnam War. However, many Democrats did not support him. Working-and middle-class voters turned against him after they found out that he might have supported abortion and making drug use legal. Also, people learned that McGovern’s first choice for vice president, Thomas Eagleton had once gotten electroshock treatment for depression. Eagleton quit, but the whole thing made McGovern look like he would make bad choices if he were president.

Nixon and the Republicans were popular from the start. Nixon’s actions, including his visit to China and a good economy helped make him popular with voters. To make sure he won, Republicans tried to make McGovern look like a radical leftist who wanted to forgive people who tried to get out of the draft. In the election, McGovern only won Massachusetts and Washington, DC. Nixon won every other state. It was one of the biggest victories in American history. Unfortunately for Nixon, his downfall had already begun.

THE WATERGATE BREAK-IN

During the election, the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP), which raised money for Nixon, decided to play “dirty tricks” on the Democrats. For example, before the vote in New Hampshire, they wrote a fake letter supposedly written by Edmund Muskie in which he made fun of French Canadians, one of New Hampshire’s largest ethnic groups. Men were sent to spy on both McGovern and Senator Edward Kennedy. Men pretended to work for the Democrats called business to rent or buy things for rallies. The rallies were never held, of course, and Democratic politicians had to pay the bills. CREEP’s most famous operation, however, was its break-in at the offices of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) in the Watergate office building in Washington, DC.

CREEP worked with G. Gordon Liddy, one of Nixon’s helpers in the White House, to make the plan for the break-in. Five men were sent to break into the offices of the DNC, take pictures of documents, and wiretap telephones. The break-in went badly. A security guard found them, and they were arrested by the police.

Breaking the law is always bad for a politician, but Nixon had not broken the law. He didn’t even know what CREEP and Liddy were planning. The problem for Nixon was his paranoia. Nixon always thought that his enemies were smarter than him, and that his friends might turn against him.

The Watergate break-in was exactly the sort of problem Nixon was most scared of. When he found out about the problem, Nixon tried to hide it, so the Democrats would not be able to use it against him.

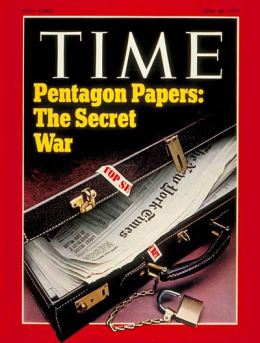

In the weeks following the Watergate break-in, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, young reporters for The Washington Post, started to find out what was going on. They got information from some people who asked that their names not be used, including one person the reporters only called “Deep Throat.” Bernstein and Woodward realized that people in the White House were trying to hide the crime. They began writing articles about what they had learned.

Woodward and Bernstein articles led the Senate to create a special committee to look into the Watergate scandal. In the spring and the long, hot summer of 1973, Americans watched the Senate investigation on television. One by one, the people who worked for Nixon admitted, or denied, their role in the Watergate scandal. The top lawyer at the White House, John Dean said that Nixon was involved in the conspiracy, but Nixon said he was not. In March 1974, the President’s Chief of Staff, H.R. Haldeman, top aide John Ehrlichman, and John Mitchell, the leader of Nixon’s reelection campaign, were charged with conspiracy in court.

Nixon fired Haldeman, Ehrlichman and Dean. Trying to show that he was innocent, he appointed a special prosecutor, Archibald Cox to investigate what happened at Watergate.

Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Reporters Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward in the newsroom of the Washington Post.

THE END OF NIXON’S PRESIDENCY

Without evidence clearly showing that Nixon had tried to hide the break-in, Nixon might have gotten away with it. But then Alexander Butterfield, who worked at the White House, was asked if there were any recordings of Nixon. In fact, Butterfield had helped Nixon set up a recording system that would turn on whenever anyone in the Oval Office talked, or any time the president was on the phone. Nixon wanted the recordings for his own use and kept them secret because he thought people would act strange if they knew they were being taped.

Cox and the Senate asked for the tapes, but Nixon said no. He said there were some things a president did not have to give to investigators. When he said he would give summaries of what was on the tape, Cox said no, and that Nixon had to give him the full recordings. On October 20, 1973, in an event that we now call the Saturday Night Massacre, Nixon told Attorney General Richardson to fire Cox. Richardson said no and quit. So did Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus when Nixon told him to do what Richardson would not. That left Solicitor General Robert Bork in charge of the Justice Department, and he did what Nixon asked.

Primary Source: Newspaper

Primary Source: Newspaper

The front page of the New York Times the day after the Saturday Night Massacre.

The American people were angry about what Nixon had done. It seemed like the president thought he didn’t have to follow the law. Angry letters started arriving at the White House from people who thought Nixon should quit. It was at this time that Nixon gave one of his most famous quotes. He was talking to news reporters and said, “I welcome this kind of examination because people have got to know whether or not their president is a crook. Well, I’m not a crook.” It turned out he was a crook.

When Nixon finally gave investigators the recordings in April of 1974, he gave only edited versions. In July, The Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Nixon that he had to hand over the full versions.

The tapes showed several key conversations between Nixon and his lawyer, John Dean. In the recordings, Dean called the Watergate investigation a “cancer on the presidency.” The men from CREEP that had been caught at the break-in were being paid not to talk and Dean said that Nixon’s top helpers were involved. In the end, Nixon himself gave orders on tape to pay off witnesses.

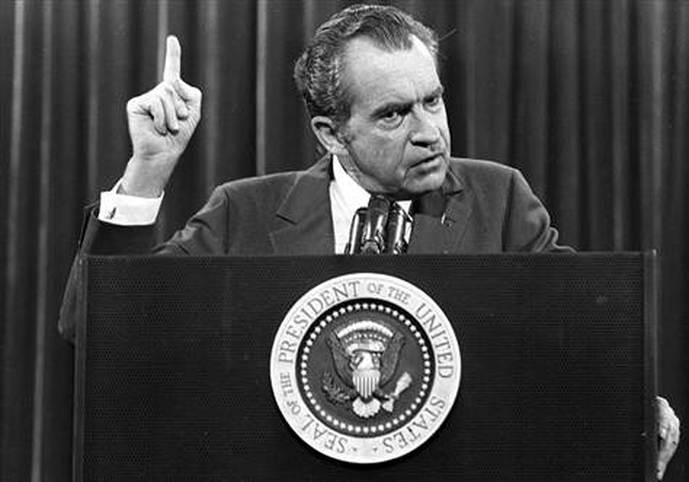

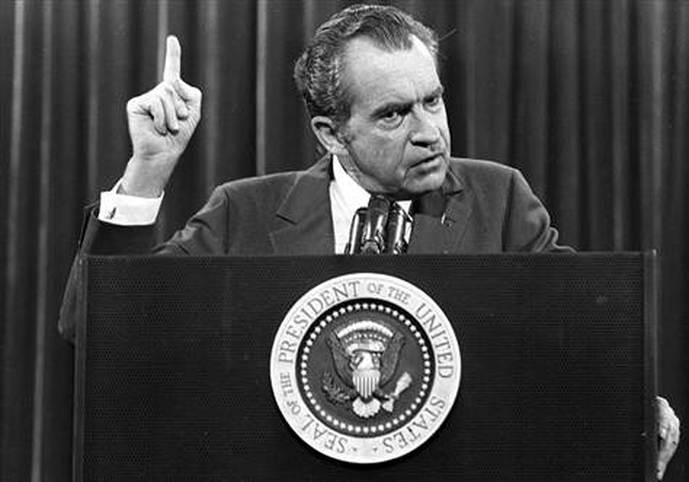

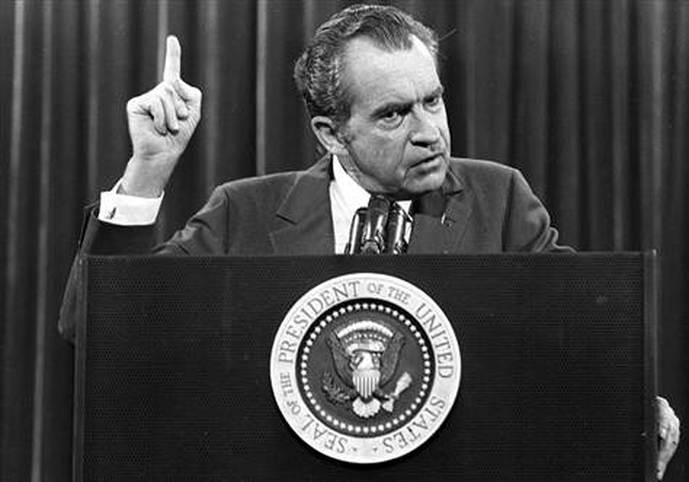

Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Nixon declares that his is “not a crook.”

It was now clear that Nixon himself had tried to hide the crime. Perhaps worst of all, he had tried to obstruct justice, or stop an investigation, by firing the special prosecutor and ordering his helpers to pay hush money to people who knew what had happened.

The release of the tapes was the end of Nixon’s power. The House of Representatives was ready to vote to impeach the president. On the night of August 7, 1974, the Republican leaders of the House and Senate met with Nixon in the Oval Office to tell him that the representatives in Congress would not stand by Nixon. They told him that he would lose his job for sure.

Knowing that he had no chance of staying on as president and that most Americans wanted him out, Nixon decided to resign, or quit. On August 9, he left the White House, the only president ever to quit.

Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Richard Nixon flashes his trademark V for victory one last time before boarding Marine One and leaving the White House after his resignation.

THE EFFECTS OF THE WATERGATE SCANDAL

Nothing like this had ever happened before. The new president, Gerald Ford was the first vice president chosen under the new 25th Amendment, which made a process for choosing a new vice president if a vice president died or quit. Nixon’s first vice president, Spiro Agnew had to quit after people learned he had been taking bribes. Nixon had chosen Ford, a member of the House of Representatives from Michigan to replace Agnew. Ford had been in government for a long time and was known for telling the truth. Ford was also the first vice president to become president after a president quit. Since he had been picked by Nixon to take over as vice president, Ford was also the only president who was never elected either president or vice president.

Ford understood that his most important job was to help people move on past the Watergate scandal. He said that “Our long national nightmare is over. Our great Republic is a government of laws and not of men.” People liked this idea but were less happy when Ford gave Nixon a full pardon, which meant that Nixon would never be put on trial or go to jail for anything he had done. Many Americans were angry. They wanted Nixon to have to pay for what he had done. In 1976 when Ford ran for president, his choice to pardon Nixon is one reason he lost.

Nixon quitting and Ford’s pardon did not make the Watergate scandal go away. Instead, it made Americans trust people in government even less. The events of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers had already shown that politicians could not be trusted. For many, Watergate was proof of what they already thought.

Today, the suffix gate added to a word has come to mean a scandal. News reporters have talked about Apple’s Bendgate and Antennagate, the NFL’s Deflategate and Seatgate, and many bad things politicians have done and called them Bridgegate, Travelgate, Emailgate, Nannygate and Strippergate, to name just a few.

THE IRAN HOSTAGE CRISIS

One of the saddest events of the late 1970s happened because of what America did in the Middle East during the Cold War and created a problem we still have today. It also showed that no matter how strong our military is, there are some things they can’t do. It all happened in Iran.

For years, the United States had helped the king, or shah of Iran because he was anti-communist. The shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi had become king during World War II and had worked hard in his thirty years to improve his country. He wanted to make Iran a modern place and gave rights to women. But Islamic religious leaders thought the Shah’s ideas were against the Quran, the Muslim holy book. In 1979, cleric Ruhollah Khomeini led students in a fight against the Shah. They took control of the American embassy in Tehran, Iran’s capital city. They took 52 Americans at the embassy hostage.

At the time, terrorism was on the rise around the globe. Arab terrorists had shot and killed eleven Israeli weightlifters at the 1972 Olympics in Munich, Germany. The Irish Republican Army (IRA) was using terrorism in their fight to make Northern Ireland free from the United Kingdom and had killed thousands of English and Irish people in car bombings. For Americans, it looked like the world was going crazy. The Iranian Revolution and hostage crisis was just another example of how the world was getting out of control.

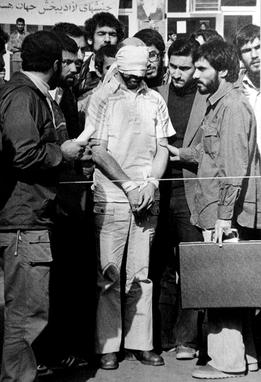

Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Iranian students carrying posters with a photograph of Khomeini climb the gate of the American embassy.

The Shah had gotten away and was in the United States. The revolutionaries said that America had to send him back to Iran in a trade for the hostages. President Carter said no, stating that the United States would “not yield to blackmail.” For 444 days, Americans watched on TV as the Iranians held the hostages. The army tried to rescue the hostages. President Carter ordered Operation Eagle Claw, but it failed in April 1980 when a helicopter and airplane crashed on their way into Iran. Eight Americans and one Iranian died. It was embarrassing for the American army and the President, who took responsibility for the crash.

Because of the hostage crisis, the failure of Operation Eagle Claw, and the bad economy, Carter lost the 1980 election to Ronald Reagan. It was one of the most uneven elections in American history. Most people remember Carter as a bad president. But Carter has worked all the rest of his life to fight for human rights around the world.

In one last insult to Carter, the new Iranian leaders, controlled by the religious leaders, let the hostages go a few minutes after Ronald Reagan became president.

Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

A photograph of American Barry Rosen released by the Iranians during the hostage crisis. Images such as these infuriated the American public who blamed President Carter for his inability to find a way to bring the hostages home.

THREE MILE ISLAND

People’s trust in our leaders went down again in 1979 at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in Pennsylvania.

On March 28, a valve in the cooling system got stuck open which let a lot of nuclear reactor coolant get out. Normally, the coolant would keep the reactor from getting too hot. Without it, the reactor would melt, and let out radioactive material. The valve failure got worse because workers didn’t notice what was happening. They didn’t have enough training and the lights in the control room were confusing. One worker thought that there was too much coolant and turned off the automatic emergency system.

By early the next morning it was clear that things were going wrong. The reactor was way too hot. The station manager announced an emergency. The electric company that owned the plant, Metropolitan Edison (Met Ed) told the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency, which then told the state’s governor, Richard L. Thornburgh. The workers at the plant weren’t sure what was happening and so people who lived near the plant got confusing messages.

Lt. Governor Scranton told the news reporters that there had been a “small release of radiation no increase in normal radiation levels” which didn’t make sense. Another leader and Met Ed both said that no radioactivity had gotten out. In fact, instruments had found that there was a release of radioactivity around the plant, but probably not enough to make people sick.

State leaders were angry that Met Ed was not telling them what was going on and was trying to make the accident look like it wasn’t serious. They turned to the Nuclear Regulatory Agency (NRC), the federal agency that checked on nuclear power plants.

The NRC sent people to Three Mile Island. NRC chairman Joseph Hendrie thought things were not too bad at first. But the NRC also had a hard time getting information and they were not prepared to take care of an accident at a nuclear power plant. Their people didn’t know who to talk to and didn’t have a plan about if they needed people to move away from the plant.

In the end, the United States was lucky. The reactor at Three Mile Island got too hot and melted, but not so much that radioactive material got out. But the Three Mile Island accident showed again that leaders, in business and technology, as well as in politics made mistakes. People learned that they should not trust their leaders to tell them the truth or protect people.

The Three Mile Island accident was also a big change for nuclear power around the world. The accident did stop people from using nuclear energy to make electricity, but it did stop people from building more nuclear power plants. At the time of the accident, electric companies were planning to build 129 new nuclear power plants, but of those, only 53 were built. Clearly, many anti-nuclear activists said, scientists and business leaders were going to take shortcuts and nuclear power was too dangerous to be used to make electricity. Around the world, people stopped building new nuclear power plants after the deadly Chernobyl accident in the Soviet Union in 1986.

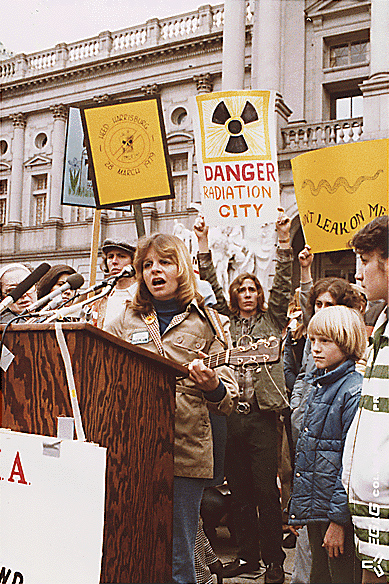

Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Anti-nuclear activists demonstrate outside the Pennsylvania State Capitol building after the Three Mile Island incident.

CONCLUSION

So, we learned from the 1970s that sometimes the people we pick for the most powerful jobs are not perfect. They make bad choices. They try to fix important problems and fail. Sometimes they lie and break the law to hide their lies. After the many sad events of the 1970s, Americans just don’t trust our leaders like we used to.

What do you think? Should we trust our leaders?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The 1970s was a period when Americans lost faith and trust in their leaders. Politicians were exposed as liars. The economy failed and leaders were not able to repair the damage, and the celebrated American industrial economy started to crumble.

The 1970s were a time when some of America’s most important leaders failed. In the case of the Pentagon Papers, reporters revealed that the Presidents of the 1950s and 1960s had lied to the American people about their real reasons for fighting the war in Vietnam, and about how the war was progressing.

President Nixon was forced to resign in 1974 when it became clear that he had abused his authority in an attempt to hide crimes committed by his supporters. The Watergate Scandal, named after the Watergate Hotel and Office Complex, along with the Pentagon Papers, marked a change in America. After the early 1970s, many fewer Americans trust presidents and other powerful leaders.

In the later decade, President Carter faced his own challenges. Although he was not corrupt like Nixon, he was unable to solve significant problems. Most embarrassingly, revolutionaries in Iran held 52 Americans hostage. Carter could not negotiate their release and a military rescue mission failed.

A meltdown at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant showed Americans that its top scientists, engineers and business leaders were also imperfect.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo: Analysts who helped write the Pentagon Papers report and released it to the press.

The Plumbers: A group of criminals that worked for the Nixon reelection team. They tried to prevent leaks of secret information that might hurt the president, but their ineptitude ultimately led to Nixon’s resignation.

George McGovern: Democratic candidate for president in 1972. He was anti-war, but lost in one of the most lopsided elections in American history.

Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP): Group that worked to fundraise for Nixon’s reelection campaign and used underhanded and illegal methods to hurt his opponents.

G. Gordon Liddy: Lawyer for CREEP and aid in the Nixon White House. He planned the Watergate break in.

Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein: Young reporters working for the Washington Post who uncovered much of the Watergate cover-up.

Deep Throat: Pseudonym for Mark Felt, Associate FBI Director who met secretly with Woodward and Bernstein and gave them information about the Watergate cover-up.

John Dean, H.R. Halderman, John Ehrlichman and John Mitchell: Aids to Nixon who lost their jobs and went to jail because of their involvement in the Watergate cover-up.

Archibald Cox: Special prosecutor appointed by Nixon to investigate the Watergate affair.

Alexander Butterfield: Minor White House official who revealed that there were secret recordings of Nixon’s conversations and telephone calls.

Gerald Ford: Vice President who became president after Nixon Resigned in 1974. He lost the 1976 presidential election to Jimmy Carter.

Ayatollah Ruholla Khomeini: Religious leader who led the Iranian Revolution and became the first leader of the theocracy.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Impeachment: The Constitutional process of removing an elected official or judge. In the case of a president, the House of Representatives serves as the prosecutors and the Senate as the jury.

Obstruction of Justice: Charge that an official uses his or her authority to prevent investigation of a crime.

Theocracy: A system of government based on a particular religion in which religious leaders hold power in government.

Anti-Nuclear Movement: A movement to end the use of nuclear power for electricity production. Despite the fact that nuclear power produces almost no pollution, activists feared the potential for catastrophic accidents.

![]()

DOCUMENTS

The Pentagon Papers: Nickname for at secret report about the Vietnam War. It was released to the public and showed that the government and military had deceived the public about the progress of the war.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Watergate Complex: Office complex and hotel in Washington, DC. It was the location of the Democratic National Committee’s offices during the 1972 presidential election.

Three Mile Island: Nuclear power plant in Pennsylvania, and site of a nuclear meltdown in 1979.

Chernobyl: Nuclear power plant in the Soviet Union (Ukraine) that melted down in 1986, released large amounts of nuclear radiation.

![]()

EVENTS

Watergate Scandal: The name for all of the crimes, investigations and ultimate resignation of President Nixon associated with the Watergate break-in and subsequent cover-up.

Watergate Hearings: Hearings in 1973 in which the Senate tried to uncover the extent of the Watergate cover-up.

Saturday Night Massacre: Nickname for the day Nixon forced the resignation of his Attorney General and the firing of Archibald Cox. The event led many Americans to believe that Nixon was trying to hide his own wrongdoing.

Nixon’s Resignation: Nixon resigned the presidency on August 9, 1974. He was replaced by Vice President Gerald Ford.

Pardon of Nixon: President Gerald Ford pardoned Nixon for any and all crimes associated with the Watergate Scandal. This ended the possibility of an investigation and trial of the former president.

Iranian Revolution: Overthrow of the Shah of Iran in 1979 and establishment of the Islamic Republic.

Iranian Hostage Crisis: The 444-day holding of 52 Americans by the new revolutionary government of Iran.

Operation Eagle Claw: Failed attempt to rescue the American hostages from Iran. The mission embarrassed the military and President Carter.

![]()

SPEECHES

“I’m not a crook”: Famous claim by Nixon to the press during the Watergate Scandal.United States v. Nixon: 1974 Supreme Court case in which the court decided that the president could not claim executive privilege to hide evidence such as the recordings of his conversations.

![]()

COURT CASES & LAWS

New York Times Co. v. United States: 1971 Supreme Court case that granted the press wide latitude in publishing classified documents with the purpose of informing the public about government activities.

United States v. Nixon: 1974 Supreme Court case in which the court decided that the president could not claim executive privilege to hide evidence such as the recordings of his conversations.

25th Amendment: Constitutional amendment providing a method for replacing the Vice President.