INTRODUCTION

After finishing his eight years as president, George Washington warned Americans not to get involved with other countries. He was worried that the new United States was too new, too weak, and might not be able to handle other countries’ problems. A little less than 100 years later the United States was a very different place. No longer a new country, America had grown. Thousands of new immigrants were working in factories and making the nation strong. The United States now stretched all the way from the Atlantic to the Pacific Oceans.

Many Americans felt that Washington’s ideas no longer applied. They felt sure the United States could use its power around the world to get what it wanted, especially after success in the Spanish-American War.

But how should the country get what it wants from other countries? Three presidents, Theodore Roosevelt, William Taft, and Woodrow Wilson all had different answers to that question. One used threats, one used money, and the last an appeal to morality.

What do you think? How should America project its power around the world?

EUROPEANS IN CHINA

For hundreds of years, Europeans have thought about how to get rich by doing business in China. After the United States beat the Spanish and won control of the Philippines with its ports where ships could refuel, American businesses were ready to make their dreams of trade with China a reality. In the beginning, Americans did very little business in China, but captains of American industry knew that there were millions of Asian customers ready to buy the things American factories were making.

American businesses were not the only ones thinking about how to make money in China. Other countries, including Japan, Russia, Great Britain, France, and Germany also hoped to open trade with China. Already in the 1840s, Great Britain had forced China to let Europeans do business in Chinese ports.

Even though Great Britain had the strongest relationship with China, other western countries started to build their own connections by sending Christian missionaries to China. In 1895, Japan defeated Chinese soldiers in battle and forced China to give up control of Korea. Germany and Russia both forced the Chinese government to let their businesses operate in China. One by one, each country made their own sphere of influence, where they could control business, and make sure they could make money from their own part of the Chinese market.

THE OPEN DOOR POLICY

Americans were worried by how fast other countries were dividing up China into these spheres of influence, and most of all, that they didn’t have their own sphere of influence in China. Unlike the Europeans, however, who each wanted their own area of China, the Americans wanted to be able to trade with people in all of China.

In 1899, Secretary of State John Hay announced the Open Door Policy. This idea was that there would be no more spheres of influence. Instead, any country could do business anywhere in China, including the United States.

On paper, the Open Door Policy seemed like it was going to make everyone equal. But it actually was very good for the United States. Free trade in China would help American businesses because their factories were making better products than anyone else and were more efficient and had lower costs. The United States could flood China with American products that would cost less and be better quality than anyone else could sell. In this way, the Open Door Policy would help the Americans while pushing the Europeans and Japanese out.  Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

Uncle Sam holds the Open Door Policy as he dictates to the European powers who hold scissors ready to divide up China into spheres of influence.

Leaders of the other countries with spheres of influence in China mostly ignored John Hay when he announced the Open Door Policy. They knew it would not be good for them. But Hay announced it anyway and American businesses started selling American products in China even though no one had told them it was ok. At first, the Chinese government welcomed the Americans because the United States had promised not to let any of China be taken away and turned into a colony. If this had happened, American businesses would have been cut out, so the Open Door Policy also protected China’s independence.

A year later, America used force to make sure it would be allowed to do business in China, but it wasn’t the Europeans or Japanese who were the enemy. It was the Chinese. A group who called themselves the Righteous and Harmonious Fists, started an uprising to get rid of all the outsiders who were controlling business in China. Americans and Europeans called them the Boxers, and to stop the Boxer Rebellion the United States, Great Britain and Germany sent 2,000 soldiers to China. This reminded other nations that the Americans were willing to use force to uphold the Open Door Policy. Later, the Open Door Policy would lead to problems between the United States and Japan in the 1930s when the Japanese tried to take control of Manchuria, the northern part of China. Primary Source: Photograph

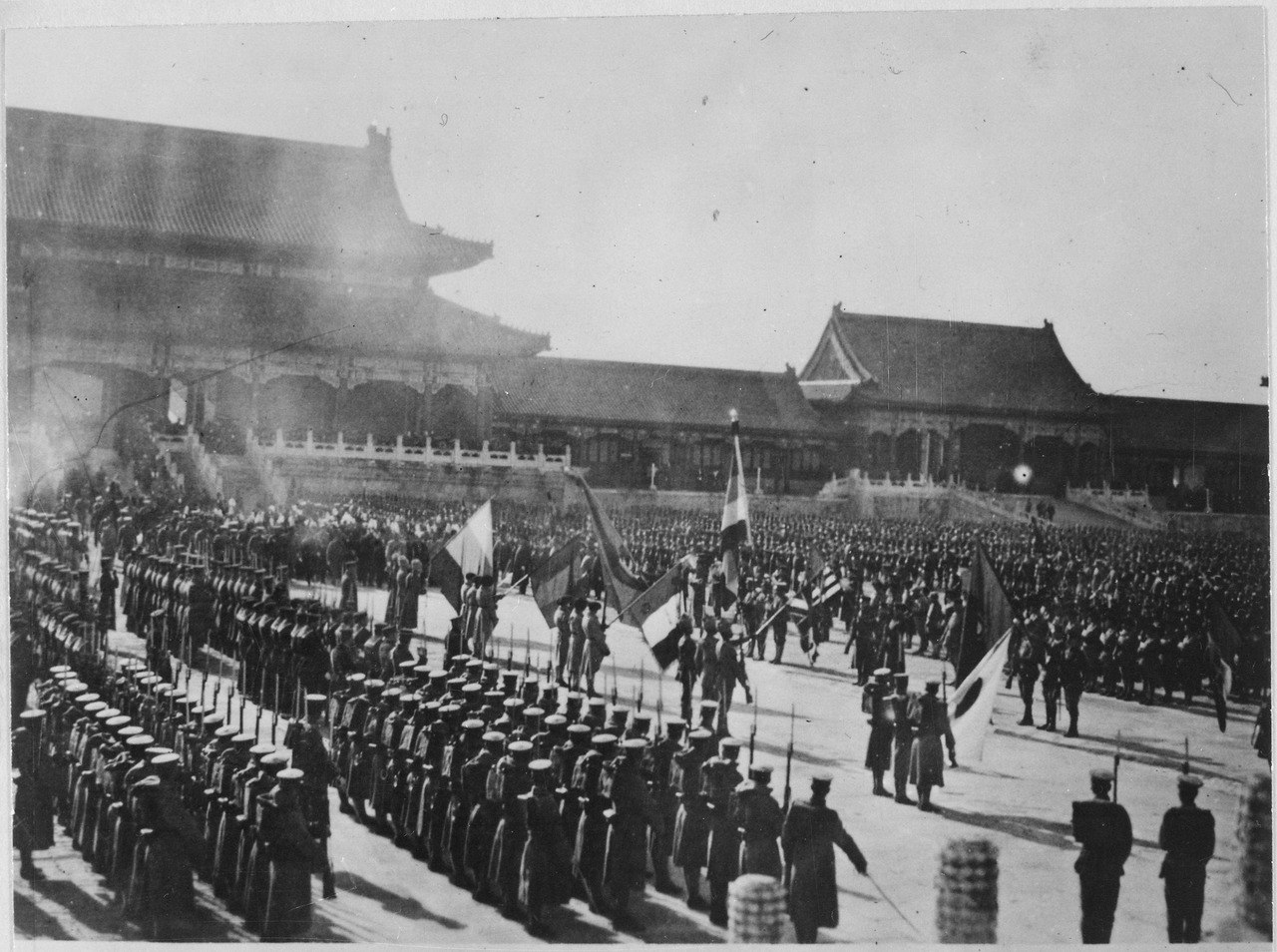

Primary Source: Photograph

International troops stand in the square in front of the Forbidden City in Beijing during the Boxer Rebellion.

ROOSEVELT’S BIG STICK

When Theodore Roosevelt became president, he tried a new way of working with other countries. His idea was based on his favorite African proverb, “speak softly, and carry a big stick, and you will go far.” The key to Roosevelt’s plan was that he would use the army and navy as the “big stick” to threaten other countries. If other people were afraid of what the United States might do, they would choose to do what America wanted.

To show how strong the United States had gotten after the Spanish-American War, Roosevelt sent the navy on a round-the-world trip between 1907 and 1909. To show friendship, the ships were painted white, but the message of the Great White Fleet was clear. America was a powerful country, and Roosevelt could reach anyone, anywhere with the “big stick.” The 16 battleships and many smaller ships made Roosevelt’s point better than any speech ever could.  Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

President Theodore Roosevelt carries his big stick as he stomps around the Caribbean Sea, pulling his navy behind him.

THE PANAMA CANAL

One of the things that had always made traveling and trade around the world hard was that North and South America are connected. The narrow bit of land connecting the two continents, the isthmus of Central America stopped ships from easily going between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The French tried to build a canal in 1881, but their plan failed, mostly because too many of their workers got sick and died from malaria and yellow fever. When he became president in 1901, Roosevelt was sure America could do what France could not. He decided to build what the world now calls the Panama Canal.

The best place to build a canal was across the 50-mile-wide isthmus of Panama, which, at the time belonged to Colombia. Roosevelt tried to get the Colombian government to give the United States permission to dig through their country, but the Columbians kept asking for more money and were taking too long to decide. Roosevelt got tired of waiting.  Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

The massive effort to dig the Panama Canal is evident in this photograph showing rail lines carrying millions of tons of dirt and rock out of the man-made canyons that would eventually be flooded to form the canal.

Roosevelt decided to use the big stick. Roosevelt started saying that the people of Panama should start a revolution to be independent from Colombia. In November 1903, he sent American battleships to the coast of Colombia. Business leaders in Panama who would become rich selling things to the Americans who came to build a canal knew what Roosevelt was telling them: Start a revolt and the American navy would be there to stop Colombia from fighting back. The Colombians also knew what it meant: Roosevelt was going to get what he wanted and there was nothing they could do to stop him.

In less than a week, Roosevelt recognized the new country of Panama and made a deal with the new Panamanian leaders to dig a canal in their country. The United States never fired a shot. It was a clear and successful use of the big stick.

Work on the canal began in 1904. In the beginning the United States worked to build houses, cafeterias, warehouses, machine shops, and support systems the French had not. Most of all, the lives of workers were protected. Dr. Walter Reed had figured out that mosquitoes spread malaria and yellow fever and he distributed mosquito nets to cover beds and got rid of puddles and other places where mosquitoes could breed.

At the same time, American engineers started to plan the canal. They decided to build a lock-system that would carry ships up and over the mountains, but digging the canal was still a huge effort. Excited by the canal project, Roosevelt became the first president to leave the country while in office when he went to Panama to see the work, taking a turn at the steam shovel. The canal opened in 1914, and it has forever changed world trade and the way the navy moves ships from ocean to ocean.

Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Never one to miss a photo opportunity, President Roosevelt took the controls at a steam shovel while touring the Panama Canal during its construction.

THE ROOSEVELT COROLLARY

Once the canal project was started, Roosevelt wanted to send a clear message to the rest of the world, and most of all to the leaders of European countries, that the colonization of the Western Hemisphere had ended, and they should not try to come back.

At the same time, he wanted people in Latin America to know that if there were problems in that region, the United States would send the army or navy to keep the peace. In other words, the United States would be the police office for the Western Hemisphere.

This idea became known as the Roosevelt Corollary. The Roosevelt Corollary was an add on the original Monroe Doctrine from the early 1800s, which warned European countries to stay out of the Americas. In this addition to the Monroe Doctrine, Roosevelt said that the United States would use its army and navy “as an international police power” to fix any “chronic wrongdoing” by any Latin American country. The Monroe Doctrine was about keeping the Europeans out, but the Roosevelt Corollary was the United States giving itself permission to get involved whenever it wanted.

Roosevelt put the new corollary to work and sent American soldiers to Cuba, Panama, the Dominican Republic, and Colombia. Later presidents would use the Roosevelt Corollary to justify American involvement in Haiti, Nicaragua, and other countries.

Even today, Latin Americans dislike what they see as Americans thinking we know best. In the eyes of many of America’s southern neighbors, being rich and strong does not give the United States the right to meddle.

THE RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR

President Roosevelt decided that the best way to get what America wanted in Asia was to keep all the Asian countries in balance with no one clearly the strongest. When a war broke out between Russia and Japan in 1904, Roosevelt set to work making sure that no one would come out much stronger than the other

As Japan’s navy won battle after battle against the Russians, Roosevelt started to worry that Japan might become the strongest country in Asia and, if it did, could take over in China and push American businesses out. Roosevelt figured it was better for America to have Russia and Japan as equals balancing each other out.

Roosevelt arranged for leaders from both countries to attend a secret peace conference. The deal they made ended the war. Russia agreed to give Japan control of Korea, some Russian army bases in northern China, and half of Sakhalin Island. For his part in helping to end the Russo-Japanese War, Roosevelt was given the Nobel Peace Prize, the first American to win this award.

TAFT’S DOLLAR DIPLOMACY

When William Howard Taft became president in 1909, he decided not to use Roosevelt’s Big Stick Diplomacy. Instead, his way of working with other countries was to use money instead of threats. For this reason, it is called Dollar Diplomacy. But Dollar Diplomacy was like Big Stick Diplomacy. In both, America got what it wanted.

THE BANANA REPUBLICS

Out of Taft’s Dollar Diplomacy grew the idea of a banana republic. The name describes a country where foreign businesses are so important that the leaders of foreign businesses have more power than the actual leaders of the country. In the early 1900s, the two best examples were the Central American countries of Honduras and Guatemala. Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

This cartoon depicts Uncle Sam with long, greedy fingers interfering in the affairs of Latin America.

In Honduras in 1910, an American businessman, Sam Zemurra helped to overthrow the government and replace the elected leaders with new people who would be friendly to American businessmen. Back home, the United States didn’t stop this from happening because the new government Zemurra had helped put in place was better for American business.

Over time, these foreign companies began to run more and more things in Honduras. They mostly grew fruits such as bananas and they built and owned the roads, railroads, ports, and telephones in Honduras. If the people, or the government ever tried to take back power from the American businesses, they just threatened to fire workers or shut down the roads. In the end, the people of Honduras voted for their government leaders, but it was American businessmen who ran the country through the power of the dollar.

A similar story played out in Guatemala. Guatemala grew and sold bananas, coffee, and sugar cane, but most people were very poor, and an American business, the United Fruit Company, owned most of the land. In the 1950s, leaders in Guatemala tried to take land from the United Fruit Company and give it to poor Guatemalans. The company leaders got the American presidents at the time to send the Central Intelligence Agency to overthrow the governments and replace them with leaders who would be more friendly to American businesses. Once again, when American dollars were in trouble, the American army was not far behind. The United Fruit Company is still strong today, but now we call it Chiquita Banana.

Another possible example of Dollar Diplomacy was American support for the overthrow of Queen Liliuokalani in Hawaii. Even though it happened before Taft was president, it is another time when the American army helped American business leaders overthrow leaders in a smaller country to make sure they wouldn’t lose money.

WOODROW WILSON’S MORAL DIPLOMACY

When Woodrow Wilson took over as president in 1913, he said that the United States would be a better neighbor. Wilson, like most Americans, thought that the United States was better than the other countries of the world, and that the American government was the best way to run a country. He wanted Americans to be able to do business all around the world. But instead of trying to force other countries to do what he wanted, he said that the United States should try to help people. For example, he liked the idea of independence for the people who lived in colonies. This was called Moral Diplomacy.

Wilson picked William Jennings Bryan to work for him as the Secretary of State. Bryan was a famous anti-imperialist and he tried to solve problems peacefully. With Wilson and Bryan in charge, the United States even agreed to pay $25 million to Colombia to apologize for what Roosevelt had done during the Panamanian Revolution.

Wilson also said he would not use the Roosevelt Corollary, Theodore Roosevelt’s plan to be the police officer in Latin America. However, Wilson found that keeping his promises was not that easy. In the end, Wilson sent the army into Latin American countries more than Taft or Roosevelt. In 1915, when the president of Haiti was murdered and a revolution got started, Wilson sent over 300 soldiers to make sure American banks would not lose money they had given to the Haitian government. One year later, in 1916, Wilson sent soldiers to the Dominican Republic to force their government to pay money they owed to American banks, and in 1917, Wilson sent soldiers to Cuba to protect American-owned sugar plantations. Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

“I’ve had about enough of this,” cries a frustrated Uncle Sam as he jumps the border to chase Pancho Villa into Mexico. As it turned out, Latin Americans had about enough of American incursions as well.

The most famous examples of Wilson breaking his promise of Moral Diplomacy happened during the Mexican Revolution. Wilson said that the fighting between different groups in Mexico had to stop and leaders there needed to let voters peacefully vote for a new government. But in reality, he wanted one side to win and even sent the navy to Mexico to stop a German ship from delivering guns to the side he didn’t like. In 1914 a fight broke out between American and Mexican soldiers and 150 people died.

When one of the Mexican revolutionaries, Pancho Villa led 1,500 of his followers across the border into the United States and attacked and burned the American town of Columbus, New Mexico, Wilson sent General John Pershing and the army into Mexico to find Villa and bring him back to the United States for trial. With over 11,000 soldiers, Pershing marched three hundred miles into Mexico but never found Villa. He did, however, make millions of Mexicans angry that Wilson had broken his promise of Moral Diplomacy once again.

CONCLUSION

After winning the Spanish-American War, American leaders tried different ways of using American power in the world.

First, Theodore Roosevelt said that a strong army and navy were the key to getting what Americans wanted, although if things were done right and the other countries were scared, the big stick would never have to fight.

President Taft talked less about fighting, but he also got what he wanted. His use of the power of American business and used the army and navy if dollars didn’t get the job done first. But for other countries, Taft and Roosevelt were about the same. They still had to do what the Americans said.

The Democrat Wilson talked about doing things differently, but his moral diplomacy ended up looking more like Roosevelt than Roosevelt himself.

Which way was right, or were they all wrong? What do you think? How should America use its power to get what it wants around the world?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: Americans wanted access to markets in China and influence in Latin America. Leaders were willing to use overt military power and economic influence to get their way.

European powers had been interested in having control in China for many years. There were important markets with lots of customers in China. Instead of taking full control and making China a colony, Europeans carved up China into zones. These spheres of influence were places where only businesses from one country could operate. The British controlled Shanghai, for example.

The United States did not like this arrangement. American leaders declared an Open Door Policy. They said that Europeans had to let American companies do business anywhere they wanted.

Some leaders in China objected to the control Europeans and Americans had in their country. In one case, a group called the Boxers launched a rebellion and the Europeans and American had to send 2,000 soldiers to defeat them.

During the early 1900s, three American presidents dealt with issues related to imperialism. The first was Theodore Roosevelt. His approach was nicknamed the Big Stick. He believed that he could use American military power (usually the navy) to intimidate less powerful nations. One example was when he sent the navy to Panama to support the Panamanian Revolution and secure the right to build the Panama Canal.

The Panama Canal was a major undertaking that was initiated by Theodore Roosevelt. The canal connects the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and allows the United States to quickly shift its warships from one ocean to the other. It also serves as an important trade route.

Roosevelt expanded the Monroe Doctrine. President Monroe had declared that the Western Hemisphere was off limits to European nations. Roosevelt added his own Corollary in which he declared that the United States would intervene in Latin American nations when there were problems. The United States has done this multiple times. This American policy has not been particularly popular south of the border.

Theodore Roosevelt won the Nobel Peace Prize for helping to negotiate an end to the Russo-Japanese War.

President Taft followed Dollar Diplomacy. He wanted to use American economic power to influence other nations. This led to the development of the so-called banana republics. One notable example was Honduras where the American United Fruit Company manipulated the government in order to pay lower taxes.

President Wilson believed in Moral Diplomacy. He wanted people to decide on their own government. However, his idealism did not extend to American territories. When Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa attacked an American town, Wilson sent the army into Mexico to try to catch him.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

John Hay: American Secretary of State who introduced the Open Door Policy.

Dr. Walter Reed: Army doctor who led the effort to eradicate mosquitos in Panama and make the area safe for the workers who built the Panama Canal.

Pancho Villa: Mexican revolutionary who led a raid on the town of Columbus in New Mexico leading to President Wilson launching an invasion of Mexico in an unsuccessful attempt to capture him.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Spheres of Influence: Nickname for the regions of China that were controlled by the various European nations. Within these zones, only one European power was permitted to carry out trade.

Banana Republic: A small nation dominated by foreign businesses. This nickname was used especially for Central American nations dominated by fruit growers based in the United States.

![]()

BUSINESSES

United Fruit Company: American company that dominated the economies of Central American nations leading to their being nicknamed Banana Republics. It is now called Chiquita Banana.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Panama Canal: Canal connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. It was an important success of President Theodore Roosevelt.

![]()

EVENTS

Boxer Rebellion: 1899-1901 conflict between Chinese nationalists and Europeans, Japanese and Americans over control of China.

Russo-Japanese War: 1904 conflict between Russian and Japan. Theodore Roosevelt helped negotiate a peace treaty and won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts.

Great White Fleet: American fleet of battleships that sailed around the world between 1907 and 1909 to demonstrate American military might.

![]()

POLICIES

Open Door Policy: American policy at the turn of the century that stated that all of China would be open to trade, essentially ignoring the European spheres of influence.

Big Stick Diplomacy: Theodore Roosevelt’s approach to foreign policy. He emphasized the threat of military force as a way to force other nations to accept American positions.

Roosevelt Corollary: Theodore Roosevelt’s addition to the Monroe Doctrine in which he stated that the United States would act as policeman for the Americas.

Good Neighbor Policy: Policy promoted by Franklin Roosevelt and other presidents that contradicted the Roosevelt Corollary. It stated that the United States would respect the independence of Latin American nations.

Dollar Diplomacy: President Taft’s approach to foreign policy. He emphasized the use of American financial power rather than the threat of military force.

Moral Diplomacy: President Wilson’s approach to foreign policy. He emphasized the use of American power to promote democracy and self-rule.