INTRODUCTION

Today, most people find out about things by watching video, sometimes on television or at the movie theaters, but more and more on our phones, and now many people are making videos themselves with their phones. But before video, people learned about what was going on in the world by reading, and the Gilded Age was a great time to be a reader or writer. Millions of Americans wanted something to read, and everyone was buying newspapers, magazines and books.

Of course, not everything that was written back then was good to read, just as not everything that is posted online now is good to watch. However, in the same way that our cameras today can show people being bad, the writers of the Gilded Age put pen to paper and tried to help people learn about problems that needed to be fixed.

What do you think? Can writers make the world a better place?

THE PRINT REVOLUTION

In a time before the Internet, smart phones, television and even radio, paper was the way Americans found out what was happening in the world. Even very small towns had at least one newspaper, and large cities had many. Many newspapers printed morning and evening editions and when breaking news happened, they made special extra editions. Hearing the newsboys on the street yelling “extra, extra” was like the alerts we get on our phones today.

Magazines came in the mail and Americans stopped at newsstands and bookstores to find things to read. In a time of reading, publishing was a big business. Some of the richest Americans were publishers.

The linotype machine, invented in 1883, made printing newspapers much faster. With this new technology and plenty of readers, anyone who could buy a printing press could make a newspaper. And it was during the Gilded Age that newspapers started to look like what we know today. Since most people had more time on Sundays, newspapers printed larger Sunday editions, divided into sections, just like we have today. To get more women to buy newspapers, fashion and beauty tips were added. And as more people watched sports for fun, a sports page was added.

Dorothea Dix became the nation’s first advice columnist for the New Orleans Picayune in 1896. Since not everyone cared about politics and world events, Charles Dana of the New York Sun invented the human-interest story. These articles told heart-warming stories about regular people like it was national news. Primary Source: Photograph

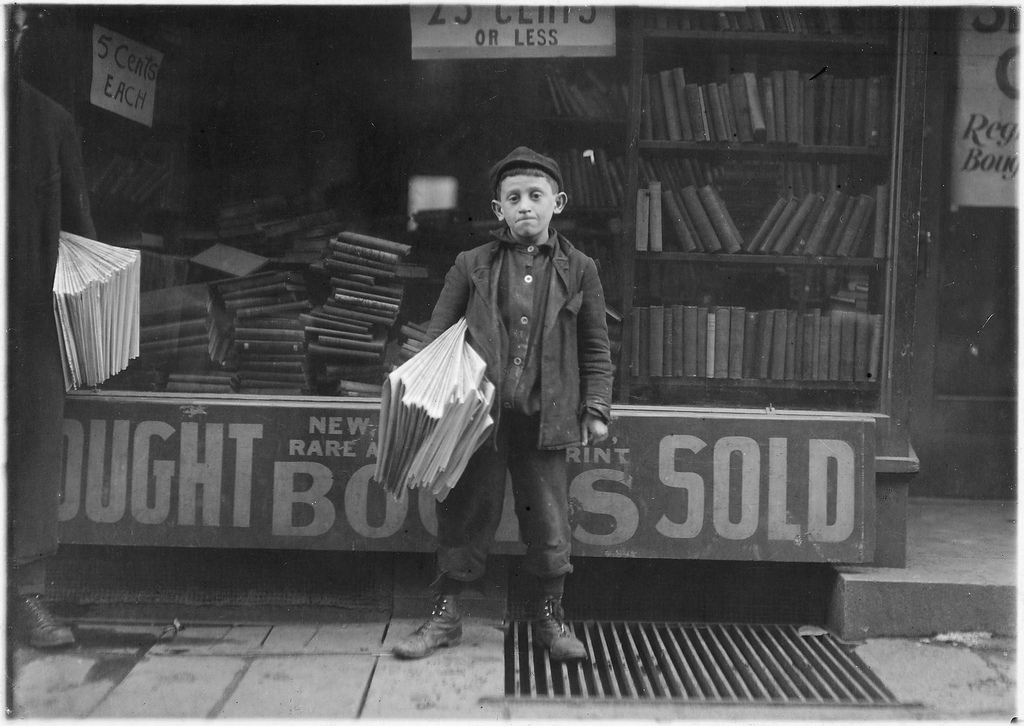

Primary Source: Photograph

One of the many newsboys who hawked newspapers in the cities at the turn of the century. This was a common form of child labor.

THE YELLOW PRESS

Publishers did everything they could to get readers to buy their newspapers, and the fight for readers was hottest in New York. The two leaders of American publishing were Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst. These men stopped at nothing to get people to buy their newspapers. If a news story was too boring, why not twist the facts to make it more interesting? If the truth was not interesting, why not spice it up with some fiction? If all else failed, the printer could always make the titles bigger to make a story seem more important.

Older news reporters thought that this was a bad idea, that it was like making up fake stories and pretending they were real. They called this new style Yellow Journalism, but even though some people criticized it, it was still popular during the Gilded Age because it worked to sell newspapers. Pulitzer increased the daily circulation of his newspaper the Journal from 20,000 to 100,000 in one year. By 1900, it had gone up to over a million.

Joseph Pulitzer bought the New York World in 1883 after making the St. Louis Post-Dispatch the main newspaper in that city. Pulitzer wanted to make the New York World fun to read, and filled his paper with pictures, games and contests that drew in new readers. Crime stories filled many of the pages, with headlines like “Was He a Suicide?” and “Screaming for Mercy.” Also, Pulitzer sold his newspaper only two cents but gave readers eight and sometimes 12 pages of information. The only other two cent paper in the city was never more than four pages long.

While there were many sensational stories in the New York World, there were lots of regular news stories also. Pulitzer thought that newspapers had to make the world a better place, and he used it to try to uncover problems so that they could be fixed.

Just two years after Pulitzer bought it, the World became the bestselling newspaper in New York. Older publishers became jealous of Pulitzer. Charles Dana, owner of the New York Sun, attacked The World and said Pulitzer was “deficient in judgment and in staying power.”

Pulitzer impressed William Randolph Hearst, the rich publisher of the San Francisco Examiner in California. Hearst read the World while studying at Harvard University and decided to make the Examiner like Pulitzer’s paper.

Under his leadership, the Examiner used 24% of its space for crime stories. Hearst added pictures on the front page. A month after Hearst took over the paper, the Examiner ran this story about a hotel fire:

“HUNGRY, FRANTIC FLAMES. They Leap Madly Upon the Splendid Pleasure Palace by the Bay of Monterey, Encircling Del Monte in Their Ravenous Embrace From Pinnacle to Foundation. Leaping Higher, Higher, Higher, With Desperate Desire. Running Madly Riotous Through Cornice, Archway and Facade. Rushing in Upon the Trembling Guests with Savage Fury. Appalled and Panic-Stricken the Breathless Fugitives Gaze Upon the Scene of Terror. The Magnificent Hotel and Its Rich Adornments Now a Smoldering heap of Ashes. The Examiner Sends a Special Train to Monterey to Gather Full Details of the Terrible Disaster. Arrival of the Unfortunate Victims on the Morning’s Train — A History of Hotel del Monte — The Plans for Rebuilding the Celebrated Hostelry — Particulars and Supposed Origin of the Fire.”

It was a great example of the yellow press style. While the fire was surely terrible, the words used to tell the story were meant to catch the reader’s attention and sell copies.

Hearst sometimes went overboard. In one article about a “band of murderers,” he attacked the police for making Examiner reporters to do their work for them. However, the Examiner also added its space for international news, and sent reporters out to find and write about corrupt and lazy city leaders.

Since so many people read newspapers, the writers had the chance to make a difference. In one well-remembered story, Examiner reporter Winifred Black went to a San Francisco hospital and found out that homeless women were treated with “gross cruelty.” The entire hospital staff was fired the morning the article was printed.

After he had made the San Francisco Examiner popular, Hearst bought the New York Journal in 1895. Primary Source: Newspaper

Primary Source: Newspaper

A classic example of the Yellow Press style, featuring bold, sensational headlines.

Big city newspapers started selling ads to department stores in the 1890s and found out that the stores would pay more if they knew the newspaper would sell more copies. So, Hearst set the price for his new New York newspaper, the Journal, at one cent (compared to The World’s two cent price) but still gave as much information as the other newspapers. The strategy worked, and as the Journal’s circulation jumped to 150,000. To keep up, Pulitzer cut the price of his newspaper to a penny also.

In a counterattack, Hearst raided the staff of the World in 1896. Pulitzer was a difficult man to work for and Hearst was willing to pay more money. Many of Pulitzer’s writers left to work for Hearst.

Although the World and the Journal were competitors, the two newspapers were similar. Both wrote stories that supported Democrats, workers, unions and immigrants. Both newspapers had large Sunday editions, which were like weekly magazines.

Their Sunday editions had the first color comic strip pages, and some historians think that the term yellow journalism started there. Hogan’s Alley, a comic strip about a boy in a yellow nightshirt, nicknamed The Yellow Kid, became popular when cartoonist Richard F. Outcault began drawing it in the World in early 1896. When Hearst hired Outcault away, Pulitzer asked artist George Luks to continue the strip with his characters, giving the city two Yellow Kids. The use of yellow journalism to mean over-the-top sensationalism seems to have started with people talking about “the Yellow Kid papers.”

Perhaps ironically, the Pulitzer Prize, which was started by Pulitzer, is given every year to the best news services in categories like Breaking News, Investigative Reporting, and Editorial Cartoons.

MUCKRAKERS

During the Gilded Age, writing letters to elected leaders and hoping that they would pass laws to fix problems was slow and didn’t usually make a difference. Publishing a series of articles could get the job done much quicker. Called muckrakers, a brave group of reporters uncovered and wrote about terrible problems in society.

The first was Lincoln Steffens. In 1902, he published an article in McClure’s magazine called “Tweed Days in St. Louis.” Steffens showed how city leaders used the city’s tax money to make deals with big businesses and stay in power. Steffens continued writing about corruption in city politics and soon put his articles together in a book called The Shame of the Cities. Readers were angry and new laws were passed to clean up the city government.

Ida Tarbell was next. Tarbell also wrote in McClure’s Magazine. She called her series of articles “A History of the Standard Oil Company.” She wrote about the cutthroat business practices behind John Rockefeller’s rise to power. For Tarbell, it was personal. Her own father had been driven out of business by Rockefeller.

The muckrakers uncovered many problems. John Spargo’s 1906 “The Bitter Cry of the Children” showed how hard life was for children who had to work in coal mines. “From the cramped position the boys have to assume,” wrote Spargo, “most of them become more or less deformed and bent-backed like old men”

In 1905, Thomas Lawson brought the inner workings of the stock market to light in “Frenzied Finance.” David Phillips showed that 75 senators were taking money from big businesses in “The Treason of the Senate.” In 1907, William Hard wrote about accidents in the steel industry in his “Making Steel and Killing Men.” Ray Stannard Baker showed how African Americans were being discriminated against in “Following the Color Line” in 1908. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

One of the many photographs taken by Jacob Riis in the slums of New York City. Photographs like this one of three homeless boys helped foster sympathy among middle and upper class Americans and foster the progressive agenda to address the problems faced by the urban poor.

Jacob Riis was an immigrant who moved to New York and worked as a police reporter. He spent much of his time in the slums and tenements of New York’s working poor. What he saw was terrible and he wrote about the life of the poor in his book “How the Other Half Lives”.

Riis was a good storyteller, using drama and photographs to tell his stories of the slums he went to. Riis was also a reformer. He thought that upper and middle-class Americans could and should care about the lives of the poor. In his book, he argued against the immoral landlords and useless laws that allowed dangerous living conditions and high rents. He also said that there should be new, better tenements.

Among the muckrakers was one pioneering female journalist who broke gender stereotypes of the day and became well known for her work finding corruption in business and government in New York City. Nellie Bly first became famous after convincing a judge that she was insane and being sent to the Blackwell’s Island lunatic asylum where she lived through the terrible treatment women there received. Her article in the New York World called “Ten Days in a Mad-House” made her famous and led to changes in the way the mentally ill were treated. She later traveled around the world by ship and train in just 72 days. There had been a popular book about traveling around the world, but no one had actually tried to see how fast the trip could be done.

Perhaps no muckraker made as big a difference as Upton Sinclair. Sinclair hoped to show how bad life was for the workers in Chicago’s meatpacking industry. His book “The Jungle”, talked about workers losing their fingers and nails by working with acid, having their arms accidentally cut off, and getting sick from working in the cold. He hoped the people who read his book would get angry and laws would be passed to make the lives of workers better.

What Americans were upset about was not, however, the hard lives of the workers. Sinclair also had written about the meat coming out of Chicago. Rotten meat was covered with chemicals to hide the smell. Skin, hair, stomach, ears, and nose were ground up and sold as head cheese. Rats climbed over the meat, leaving piles of excrement behind.

Sinclair said that he had hoped to hit America’s heart but hit its stomach instead. Even President Roosevelt, who had come up with the name muckraker, took action. In just a few short months, Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act to clean up the country’s food supply. Because of Sinclair’s book, today the Food and Drug Administration keeps an eye on the country’s food and medications to protect us from the problems Sinclair found.

MAGAZINES

Along with newspapers and books, magazines gave Americans news, information and entertainment during the Gilded Age.

Weekly magazines like Puck, McClure’s, Collier’s and the Saturday Evening Post became popular during the Gilded Age. They were normally about 32-pages long and had a full-color cover, sometimes of a political cartoon. Inside were articles about politics, fashion, human interest stories, humor, pictures, letters, and poetry. They also published novels, one chapter at a time. In this way, McClure’s published such writers as Arthur Conan Doyle, Rudyard Kipling, Jack London, Robert Louis Stevenson, Ray Bradbury, Agatha Christie, William Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Edgar Allan Poe, and Mark Twain. Some of America’s most famous novels were first printed one chapter at a time in the magazines of the Gilded Age.

As we already mentioned, magazines included the work of some of the most famous muckrakers. Primary Source: Magazine Cover

Primary Source: Magazine Cover

The Saturday Evening Post was known for featuring illustrated covers highlighting everyday life.

The Saturday Evening Post was known for featuring illustrated covers highlighting everyday life. Some Post covers became popular and continue to be printed as posters, especially those by Norman Rockwell.

Weekly magazines such as Puck, McClures, Collier’s and The Saturday Evening Post were popular for nearly half a century until the 1950s when Americans turned to a new form of entertainment: television.

CONCLUSION

The printed word in the Gilded Age caught the imagination of America. Sometimes it made us cry, or laugh, or become angry. But whatever the effect, the editors, artists, reporters, and authors of the Gilded Age made a difference. They brought down corrupt politicians and exposed cheating businessmen. They gave us some of America’s great stories.

On the other hand, exaggerated headlines got people angry enough to demand that America go to war and half-truths were sold as news as the publishers tried to get rich.

What do you think? Can writers make the world a better place?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: In the late 1800s, newspaper publishers competing for readers developed the Yellow Press style of sensational headlines and articles. This led to misleading journalism, but also fueled the muckrakers who exposed corruption and scandal in politics and business.

The beginning of the 1900s was a time of growth in the print industry. Before the Internet, radio or television, most people got their news from newspapers, and even small cities had multiple newspapers that were printed twice a day. Two great publishers, Pulitzer and Hearst competed for subscribers and developed a style of sensational journalism that exaggerated the truth and used flashy headlines to catcher potential readers’ attention. Called Yellow Journalism, it was both good and bad.

The Yellow Journalists loved publishing stories that exposed wrongdoing by politicians and business leaders. These muckrakers did America a great service by showing the wrongs of city life, the meat packing industry, robber baron practices, and government corruption. Some of their work led directly to changes in laws that made American better. The best-known example is the connection between Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and the passage of the Meat Inspection and Pure Food and Drug Acts.

This was a time period of growth in magazines as well. Weekly publications such as Puck, McLure’s, Collier’s, and the Saturday Evening Post grew in popularity and remained a staple of American life until after World War II when television replaced reading as a favored pastime.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Journalist: A person who researches, interviews and then writes stories for newspapers, magazines, radio, television, or online publications.

Dorothea Dix: Turn of the century social reformer and journalist. She invented the advice column for newspapers.

Joseph Pulitzer: American newspaper publisher who helped pioneer the style of yellow journalism. His primary rival was William Randolph Hearst.

William Randolph Hearst: American newspaper publisher who helped pioneer the style of yellow journalism. His primary rival was Joseph Pulitzer.

Muckraker: A journalist at the turn of the century who research and published stories and books uncovering political or business scandal. The term was coined by President Theodore Roosevelt.

Lincoln Steffens: Muckraker and author of The Same of the Cities about corruption in city governments.

Ida Tarbell: Muckraker and author of a tell-all book about John D. Rockefeller and the rise of Standard Oil.

Jacob Riis: Muckraker, photographer and author of the book How the Other Half Lives about the life in city slums.

Nellie Bly: Muckraker who wrote about corruption in New York government and business and traveled around the world in 72 days.

Upton Sinclair: Muckraker and author of The Jungle about working and sanitary conditions in meat packing plants in Chicago at the turn of the century.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Human Interest Story: A type of news story that focused on emotional stories rather than breaking news.

Yellow Journalism: A style of newspaper writing pioneered by Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst at the turn of the century featuring bold headlines, images and sensational stories designed to capture readers’ attention and sell papers. This style is generally credited with inflaming public opinion in the lead up to the Spanish-American War.

Pulitzer Prize: An annual award for excellence in journalism, ironically named after one of the trade’s most notorious promoters of the yellow press.

![]()

BOOKS & MAGAZINES

The Shame of the Cities: Lincoln Steffens’ book about corruption in major American cities at the turn of the century.

How the Other Half Lives: Jacob Riis’s book of photographs about life in city slums at the turn of the century.

The Jungle: Upton Sinclair’s book about working and sanitary conditions in meat packing plants in Chicago at the turn of the century.

Puck: Weekly magazine popular at the turn of the century. It was originally published in St. Louis in German.

McClure’s: Weekly magazine popular at the turn of the century that featured literature by famous authors and ran the work of muckrakers including Ida Tarbell’s expose of Standard Oil.

Collier’s: Weekly magazine popular at the turn of the century. It ran numerous stories by muckrakers including The Great American Fraud which exposed abuses in the pharmaceutical industry.

The Saturday Evening Post: Weekly magazine popular at the turn of the century and well into the 1950s. It featured paintings on the cover depicting scenes of daily life, most notably by the artist Norman Rockwell.

![]()

GOVERNMENT AGENCIES

Food and Drug Administration: Organization in the federal government charged with monitoring the food and pharmaceutical industries.

![]()

TECHNOLOGY

Linotype Machine: An 1883 invention that allowed for fast printing of newspapers. It helped lead to a boom in newspaper publishing at the turn of the century.

![]()

LAWS

Pure Food and Drug Act: Law passed in 1906 providing public inspection of food and pharmaceutical production. It was inspired in part by Upton Sinclair’s book The Jungle.

Meat Inspection Act: Law passed in 1906 providing regulation of the meat industry. It was inspired in part by Upton Sinclair’s book The Jungle.