INTRODUCTION

The First World War was a total war. In wars in the 1800s and before, regular people had to help with food and clothes, but because of the Industrial Revolution World War I was very different. Modern communication and technology meant that everyone had to support the armies and navies, or the country would lose for sure. Governments used every type of communication they could think of to spread pro-war propaganda. In the United States, the whole country was changed so that the Allies would win.

During peacetime, businesses buy and sell, invest, make money and fail on their own, and the government does not get involved. That is what has made America’s economy so strong for so long. However, during the war, businesses needed to make the things the army needed, and the country’s farms, trucks, railroads, telegraphs, and telephones all needed to work together to make sure the army had what it needed to win. Victory would only be possible if everyone was working in harmony.

To make this happen, the federal government in Washington, DC took over the job of managing the farms, the railroads, the communications networks, industry, labor relations, and even took on the job of advertiser in order to promote pro-war attitudes among the people. Never before in American history had the government been so powerful.

Was this a good idea? Government control of the economy seemed like a way to increase the country’s chances of winning the war, but it also limited people’s right to make their own decisions. The government even made laws limiting what people could say or write so that there would be 100% support for the war.

What do you think? Are limits on basic freedoms ok in times of crisis?

MOBILIZING THE NATION

Both the Allied and Central Powers had been fighting for years and neither side was winning. Both sides were running out of men and supplies. Wilson knew that the United States needed to get men, money, food, and supplies so that they could make a difference and help the Allies win.

In 1917, when the United States declared war on Germany, the army was only the seventh largest in the world. There were only 200,000 men in the American army. Germany had 4.5 million men when it had started the war back in 1914 and over 11 million more soldiers had joined the German army since then. It if was going to defeat the Central Powers, America would need more soldiers.

To build up the army, Congress passed the Selective Service Act in 1917, which said that all men aged 21 through 30 had to register, or sign up for the draft. In 1918, the act was changed so that all men between 18 and 45 had to register. With the draft, the government could force men into the army even if they did not want to join. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Men lined up to register for the draft early in the war.

Overall, many American men were eager to sign up for the draft. The government did a good job of convincing them that it was a good way to show their love for their country, and they also made it easy to register. Over 10 million men registered for the draft on the very first day. By the war’s end, 22 million men had registered for the draft. Only 5 million of these men were actually drafted into the army. Another 1.5 million volunteered, and over 500,000 men signed up for the navy or marines. In all, 2 million Americans fought in Europe during the First World War. Among the volunteers were also 22,000 women. Most of the women were nurses or worked in office jobs in France supporting the army.

Certainly, many Americans were excited about helping their country. Some of the most eager were New Immigrants from Europe and their children. Serving in the army was a way to show their love for their new country. However, not everyone liked the draft, and almost 350,000 Americans who should have registered for the draft said they would not. About 65,000 were conscientious objectors. They said that they could not serve in the army because of their religion. It was not easy to be a conscientious objector. Sometimes these men were on trial for breaking the draft law. Courts handed down over 200 prison sentences, and 17 death sentences for Americans who would not join the army.

There was a dark side to the overall excitement about the war. Wars seem to bring out the worst prejudices in people, and since many Americans could not tell the difference between Germans in Europe and German Americans at home, many German Americans were attacked. Children got attacked at school, and yellow paint was thrown on front doors. One German American was killed by a mob in Illinois.

Anti-German feelings were so strong in some places it seems silly to students today. Colleges and high schools stopped teaching the German language. The city of Cincinnati made pretzels illegal, and orchestras stopped playing music by German composers. Hamburgers, sauerkraut, and frankfurters became known as liberty meat, liberty cabbage, and hot dogs. Even the temperance movement that was trying to make alcohol illegal received a boost by linking beer drinking with support for Germany.

THE POWER OF GOVERNMENT

World War I led to important changes in the federal government’s relationship with business. Most importantly, the government gave itself more power to tell private businesses what to do.

With the size of the army growing, the government needed to make sure that there were enough supplies, such as food and fuel, for both the soldiers and the people at home. To solve this problem, Congress passed the Food and Fuel Control Act, which gave the president the power to control farms, railroads and trucks, and the price of food during the war. Using this law, Wilson created both a Fuel Administration and a Food Administration. The Fuel Administration came up with the idea of fuel holidays to try to get Americans to support the war by only using gasoline on some days of the week. The Fuel Administration started daylight saving time for the first time in American history. By having everyone move their clocks during the summer, businesses could stay open when the sun was out instead of using electricity. Herbert Hoover coordinated the Food Administration, and he got people to use less. With the slogan “food will win the war,” Hoover came up with “Meatless Mondays,” “Wheatless Wednesdays,” and other ideas to get people to eat less, with the hope of saving food for the army and navy to use. Primary Source: Propaganda Poster

Primary Source: Propaganda Poster

While British, French, German and other European farmers were fighting fighting, American farmers provided the food that save the lives of much of the population of Europe.

Wilson also created the War Industries Board, run by Bernard Baruch, to make sure the army and navy had enough supplies. The War Industries Board had control over raw materials, as well as control over businesses that made things for the government. Baruch offered businesses good deals if they would change their factories to make things for the army or navy. For those businesses that did not want to help, Baruch’s control over raw materials gave him the power to get them to change their minds.

As a way to move all the people and supplies around the country easily, Congress created the U.S. Railroad Administration. This agency had power to control the railroad industry, traffic, terminals, rates, and wages.

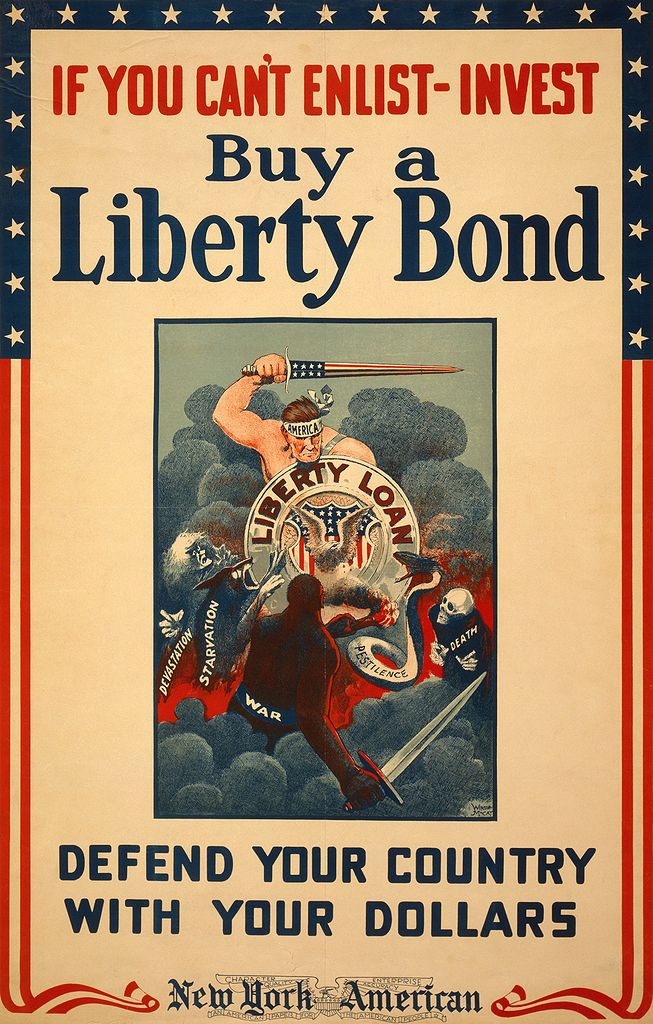

With the whole country set up to fight and win the war, the only thing left was to figure out how to pay for it. The war was going to cost the government a lot of money. In fact, the war cost the government $32 billion in total. To raise this much money, the government sold liberty bonds, telling people to “do their part” to help the war effort and bring the soldiers home. Liberty bonds were a way for the government to borrow money from regular people. People could turn in their bonds five or ten years later and get their money back, plus a little more in interest. The government raised $23 billion by selling liberty bonds. The rest of the money needed for the war came from federal income taxes, which was possible because the Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution had just been passed in 1913. With money in place, the last thing that was needed to make sure America could win the war, was to make sure that everyone supported their government and their soldiers.

LIMITING FREEDOMS

After years of immigration, American leaders were worried that not everyone would be eager to support the war. After all, not everyone had supported the vote to join the war.

Wilson needed to make sure that everyone, even new immigrants who had come from the countries that were fighting against the United States, thought of themselves as American first, and Germans for Austrians second. Wilson created the Committee on Public Information to make propaganda. He chose George Creel to lead this new government agency and to make the propaganda, or advertising needed to get everyone to support the war. Creel organized rallies and parades. He paid popular musicians to write patriotic songs. One song, “Over There” became a hit. Artists made dozens of posters telling Americans to do everything from saving fuel to joining the army. The famous picture of Uncle Sam looking at young American men saying “I Want You for the U.S. Army” was made by Creel’s team during World War I. Movies and plays added to the excitement. The Creel Committee did a good job of getting millions of Americans to support their government and the war effort. Primary Source: Propaganda Poster

Primary Source: Propaganda Poster

Images like these were important elements of the government’s propaganda campaign to convince Americans to support the war effort.

Still there were some people who didn’t want the United States to be a part of the war. The American Socialist Party was one of these groups. Many Irish Americans didn’t like Great Britain, who they saw as an enemy and not an ally. Millions of immigrants from Germany and Austria-Hungary had to support a war that was being fought against their homeland. Even though it was actually just a small number of people who were against the war, the government still tried to stop anti-war talk with a law when Congress passed the Espionage and Sedition Acts of 1917. Anyone found guilty of criticizing the government’s war plans or trying to stop the war effort could be sent to jail. Many cried that this was clearly against the First Amendment’s protection of the right to free speech. But the Supreme Court decided in the Schenck v. United States case that the government could limit a person’s free speech if that person was a “clear and present danger” to others. Schenck had been arrested for trying to stop people from registering for the draft. The Court ruled that this had put thousands of American lives in danger because he had stopped people from becoming soldiers. Another famous person who went to jail for violating the Espionage and Sedition Acts was Socialist Party and union leader Eugene V. Debs.

ORGANIZED LABOR SUPPORTS THE WAR

Even though President Roosevelt had decided that it was the role of government to help unions and business owners work together, presidents had mostly stayed out of these fights. But World War I changed this. The army and navy needed supplies and strikes would hurt the war effort. Samuel Gompers, leader of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), saw the war as a chance to get better pay and working conditions for American workers by getting the government on his side. And, with the government needing so many more supplies, and so many men leaving to join the army, all over America there were factories that needed workers. The result was that the government was ready to step in and make sure that workers were happy with their pay, and that business owners who were selling supplies to the army were making plenty of money.

To make all this happen, President Wilson started the National Labor War Board. Working with Gompers and the AFL, the government got labor unions to promise not to go on strike during the war. In return, the government promised to make sure that workers could join unions and bargain collectively. The federal government kept its promise and helped make the eight-hour workday common. During the war, union membership went up from 2.6 million members in 1916 to 4.1 million in 1919. In short, American workers got better working conditions and pay because of the war. But the war was not all good for workers. Business owners also got rich selling things to the army and navy. And, even though pay went up, so did prices on many things, so workers needed more money to buy things when they went shopping, so they didn’t feel like they had more money.

WOMEN IN WARTIME

The war both helped and hurt women. As men left for the army, many women were able to get jobs that were only held by men before. However, as prices went up, things became more expensive, and this hurt some women and their families. More than one million women started working for the first time because of the war, while more than eight million women who already were working, got better paying jobs, often in factories or on the railroads.

After the war ended and men came home, women were fired from their jobs, and were told to go back to their homes to take care of their families. Also, even when they were doing men’s jobs, women were usually paid less than men, and unions did not usually help women workers. But still, women who went to work during the war got to know a different kind of life from the one they had before. They found out that they didn’t have to stay at home, but that having a job was possible. Twenty years later, World War II would have the same effect on another generation of women, and by the time the granddaughters of the women workers of World War I were old enough to work, the rules about women having to stay home started to break down forever. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Women found jobs open to them during wartime that had never been open before.

One famous group of women who took advantage of these new chances to work was the Women’s Land Army of America. First during World War I, and then again in World War II, these women stepped up to run farms as men left for the war. Known as Farmerettes, some 20,000 women, mostly educated women from the cities, went out to the countryside to join the Land Army. For some, it was a way to serve their country during a time of war. Others hoped to help women win more rights, like the right to vote.

Also, about 30,000 American women served in the army and navy, as well as groups like the Red Cross and YMCA, during the war. Women served as nurses and telephone operators in France. Of this latter group, 230 of them, known as “Hello Girls,” knew more than one language and worked near the front lines helping the American soldiers work with their French Allies. Over 18,000 American women served as Red Cross nurses. Close to 300 nurses died during the war. Many of those who came home kept working in hospitals helping soldiers who had been hurt during the war.

AFRICAN AMERICANS AND THE DOUBLE V CAMPAIGN

African Americans also found that the war led to new opportunities and changes. African Americans made up 13% of the men of the army, with 350,000 men serving. African Americans served in segregated units and often had to do basic or supporting jobs because of racism, which was common.

Some troops saw combat, however, and were given awards for heroism. The 369th Infantry, for example, known as the Harlem Hellfighters, served on the frontline of France for six months, longer than any other American unit. 171 men from that regiment won the Legion of Merit in the war. The regiment marched in a homecoming parade in New York City and was celebrated for bravery. But their experience was different from most African Americans during the war.

On the home front, African Americans, like American women, had new chances to work during the war. Nearly 350,000 African Americans found work in mines, shipbuilding yards, steel and automobile factories. African American women also found new jobs beyond just being housekeepers. Even still, racism still limited jobs African Americans could get in both the North and South. Worried about large numbers of African Americans coming to their cities for factory jobs, several cities in the North made laws to stop African Americans from moving into some neighborhoods. There were more race riots. In 1917 alone, there were race riots in 25 cities, including East Saint Louis, where 39 African Americans were killed. In the South, White business and plantation owners were worried that their workers would move north for factory jobs and used violence to scare African Americans into staying. Lynching went up from 38 in 1917 to 83 in 1919. These numbers did not start to come back down until 1923, when the number of annual lynchings dropped below 35 for the first time since the Civil War. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Members of the 369th Infantry, better known as the Harlem Hellfighters. Like many African American men during the war they were fighting both against the Kaiser’s army on the field in Europe and against prejudice at home.

CONCLUSION

Wars create a lot of change, and even though World War I was not fought in America, it did bring about a lot of change for many Americans. Women and African Americans got new chances to work, and labor unions got help from the government they had not expected.

By far, however, the most important change was the way the government got involved in the lives of regular Americans. Before the war, the only connection most people had with the government was when they went to the post office, or every other year on election day when they went to vote. World War I changed that forever. Because of the war, the government took on the power to control such everyday things as the price of milk, and what you could or could not say to your friends.

Of course, the country had to do what it needed to do to win once it joined the war, but was so much government power a good thing? Were laws such as the Espionage and Sedition Acts or rules about food prices and railroad schedules ok, or is there nothing, not even war, which makes it ok for the government to have so much control over our lives?

What do you think? Are limits on basic freedoms ok in times of crisis?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: World War I had profound impacts on the United States. Although there was never any fighting on American soil, it led to the expansion of the government, new opportunities for women and African Americans, as well as regrettable restrictions of the freedom of speech.

Americans were enthusiastic about joining the army. For many recent immigrants and their children, joining the fight was a way to demonstrate their love for their new country. A draft was implemented. There were a few conscientious objectors.

Anti-German feelings were common. There were many German immigrants and they faced discrimination. Schools stopped teaching German and German foods were renamed at restaurants.

The federal government gained in both size and power during the war. Business leaders and government officials collaborated to set prices and organize railroad schedules in support of the war effort. Future president Herbert Hoover organized the food industry and the United States fed both its own people and the people of Europe during the war.

To pay for the war, the government raised money by selling liberty bonds.

One of the dark sides to World War I were laws passed to limit First Amendment freedoms. The Espionage and Sedition Acts made criticizing the government and the war effort illegal. In the case of Schenck v. United States, the Supreme Court upheld these restrictions.

The war effort was good for organized labor. Labor unions worked closely with government officials who wanted to avoid strikes. It was during the war that the 8-hour workday was implemented. Pay went up as well.

Women took some jobs in factories and supported the war effort as nurses and secretaries.

For African Americans, the war was a chance to demonstrate their bravery in battle. Although they served in segregated units, African Americans were fighting against both Germany and discrimination back home. During the war, the need for factory workers in the North increased and thousands of African American families moved out of the rural South to the cities of the North to find work. This Great Migration significantly changed the racial makeup for the country.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Conscientious Objectors: People who refuse to join the military for personal, moral reasons, such as because of religious beliefs.

Herbert Hoover: Director of the Food Administration during World War I, and later president.

Bernard Baruch: Director of the War Industries Board during World War I.

George Creel: Director of the Committee on Public Information during World War I.

Harlem Hellfighters: Nickname for the 369th Infantry, a segregated unit of African-American soldiers during World War I.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Draft: System in which the government legally compels citizens to join the armed forces.

Daylight Savings Time: System in which clocks are moved forward one hour in the spring, thus allowing for more daylight hours during summer evenings.

Propaganda: Advertising created by the government to encourage citizens to think and act in ways the government wants.

Eight-Hour Day: Traditional work-day that was established during World War I.

![]()

GOVERNMENT AGENCIES

Fuel Administration: Government agency during World War I that managed rationing of gasoline and oil.

Food Administration: Government agency during World War I run by Herbert Hoover that managed rationing of food supplies.

War Industries Board: Government agency during World War I run by Bernard Baruch which directed production, distribution and wages. It is an example of significant government involvement in private industry.

U.S. Railway Administration: Government agency during World War I that managed the nation’s railway networks in order to support the war effort.

Committee on Public Information: Government agency created during World War I and run by George Creel to produce pro-war, pro-government propaganda.

National Labor War Board: Government agency created during World War I to negotiate with labor unions and prevent strikes.

Women’s Land Army: Government agency which employed women on farms to replace men who had joined the army.

![]()

SONGS

Over There: Most popular song during World War I.

![]()

COURT CASES

Schenck v. United States: Supreme Court ruling during World War I upholding the Espionage and Sedition Acts. It introduced the “clean and present danger” doctrine but is not widely considered to be a failure of the Court to preserve individual liberties.

![]()

LAWS

Selective Service Act: 1917 law that established the draft.

Lever Act / Food and Fuel Control Act: Law passed during World War I granting the president power to control production, distribution and price of food.

Liberty Loan Act: Law passed during World War I empowering the government to borrow billions of dollars by issuing war bonds.

Espionage and Sedition Acts: A pair of laws passed during World War I significantly restricting freedom of speech by making anti-war or anti-government speech illegal.