JUMP TO

TRANSLATE

OTHER VERSIONS OF THIS READING

INTRODUCTION

We can think about the story of American women as times of lots of activity separated by times when very little was going on, and the Progressive Era was a time when a lot was changing for women. Many of the progressive reformers were women, and many of the things the progressives worked on were important to women. Mostly White, upper-middle-class women, many had gone to college and felt like they needed to put their skills to use. About half of these women never married, choosing independence instead.

For women who did not go to college, life was much different. Many single, middle-class women took jobs in the new cities. Office jobs opened as typewriters became common in businesses. Telephone systems needed operators to connect calls and the new department stores needed salespeople.

For others, life was not as exciting. Wives of immigrants often took extra tenants called boarders into their already crowded tenement homes. By giving food and doing laundry, they could make a little extra money for the families. Many also did housework for middle class families to make extra money.

Of all the changes Progressive women won, probably the most important was the right to vote. Women had been fighting for suffrage for over 100 years and when the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920, over 100 years of hard work finally paid off.

But did women have to win the right to vote in order to make their lives better? What do you think?

VICTORIAN VALUES

The 1800s are often called the Victorian Age, named after Queen Victoria of Great Britain, who was queen from 1837 to 1901. The time was one of conservative social rules, especially for women. The social rules in America were similar to the rules of Europe, and people in both places thought that men and women should have different jobs in life. The male sphere included paid work outside the home and politics, while the female sphere was all the things done inside the home like cleaning, cooking and raising children. In the United States, historians call this idea the Cult of Domesticity.

Industrialization and urbanization challenged Victorian ideas. Men got tired of working long hours and wanted to enjoy some of the new chances to relax that were becoming popular. More women were going to school, but after graduation they found that there was almost no place that would hire them. Also, many immigrants had never learned about the old Victorian way of thinking about men and women.

The leaders of this new change were the young, single, middle-class women who worked in the cities. People were starting to think differently, but almost no one was brave enough to talk about it.

Almost no one except Victoria Woodhull. In 1871, she said that she had the right to love whoever she wanted. She called this free love.

Woodhull’s support of free love probably started after she found out that her first husband was cheating. Women who got married in the United States during the 1800s were stuck. Divorce was usually illegal and women who could get divorced were social outcasts. Victoria Woodhull decided that women should have the choice to leave unhappy marriages.

Woodhull thought that monogamous relationships were best, but she also said she had the right to change her mind. In her view, the choice to have sex or not was, in every case, the woman’s choice, since this would make her equal to the man.

Woodhull said of free love, “Yes, I am a Free Lover. I have an inalienable, constitutional and natural right to love whom I may, to love as long or as short a period as I can; to change that love every day if I please, and with that right neither you nor any law you can frame have any right to interfere.”

To be sure, not everyone agreed.  Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Victoria Woodhall, Champion of Free Love

Woodhull was angry that many people put up with men who had affairs when they were married, but said she was wrong for believing in free love. In 1872, Woodhull attacked a popular minister, Henry Ward Beecher. Beecher had an affair with one of the women who attended his church, and the scandal was written about in the country’s newspapers. But in the end, Woodhull was put on trial for attacking Beecher in her writings.

Woodhull didn’t like it that men controlled everything in politics, so she ran for President in 1872. She was the first American woman to do so, and it was in a time before women could even vote. Since she was already famous for criticizing Beecher and being put on trial, the newspapers wrote a lot about her run for president. Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

“Get thee behind me, Satan!” In this 1872 cartoon by Thomas Nast, a wife carrying a heavy burden of children and a drunk husband, admonishes Satan (Victoria Woodhull), “I’d rather travel the hardest path of matrimony than follow your footsteps.” Mrs. Satan’s sign reads, “Be saved by free love.”

BIRTH CONTROL

For many women reformers of the Gilded Age, legalizing birth control, or contraception, was a main way they thought women could get equal rights to men. In the 1800s, contraception was often under attack from church groups. These anti-contraception groups thought birth control was wrong and that it would lead to prostitution and venereal disease. Anthony Comstock, a postal inspector and leader of the anti-contraception movement got Congress to pass the Comstock Act 1873. This law made it illegal to mail anything that would help someone with birth control or abortion, or even to send information about birth control. After the Comstock Law was passed, women who supported birth control had to be secretive about their work. Drugstores still sold condoms and cervical caps but called them “rubber goods” and “womb supporters.”

By 1900, a group of women decided it was time to get rid of the Comstock Act and laws like it that made talking about contraception illegal. Many of these women lived near one another in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City, and the most influential was Margaret Sanger. In 1913, Sanger was working with poor women who had severe medical problems that were the result of giving birth and being pregnant often. Some of the women Sanger worked with also had medical problems from abortions they had tried to do themselves. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Margaret Sanger surrounded by her supporters as she exits a New York courthouse after one of her multiple encounters with the anti-contraception legal system.

Sanger decided that the Comstock Acts were wrong because they limited her freedom of speech. In 1914, she started The Woman Rebel, an eight-page monthly newsletter that promoted contraception using the slogan, “No Gods, No Masters.” Sanger said that each woman should be in control of her own body. She is the one who came up with the term birth control, which was first used in her newsletter. Sanger’s goal of challenging the Comstock Law finally happened in August 1914 when she was put on trial. However, the government lawyers focused on articles Sanger had written about marriage and not those about contraception. Afraid that she might be sent to jail without a chance to argue for birth control in court, Sanger escaped to England. While she was in Europe, Sanger’s husband continued her work, and he was also arrested.

New York state law made it illegal to share information about birth control, but Sanger hoped to get around that rule because the law also gave doctors permission to share information about stopping the spread of disease. On October 16, 1916, she opened the Brownsville Clinic in Brooklyn, New York. It was a success, with more than 100 women visiting on the first day. A few days after the clinic opened, an undercover police woman bought a cervical cap at the clinic, and Sanger was arrested. Refusing to walk, Sanger and a coworker were dragged out of the clinic by police officers. The clinic was shut down, and no other birth-control clinics were opened in the United States until the 1920s. However, the newspapers wrote about Sanger’s trial and many people thought that what Sanger was doing was a good idea. By the end of 1917, more than 30 new pro-birth-control groups had been started in the United States.

After Sanger’s trial, the birth-control movement began to grow. It wasn’t just a few radical women in New York anymore. Now, progressive women all over the country were starting to think about how birth control might help women have healthier and better lives. Sanger’s organization grew, changed names, and today is called Planned Parenthood. All over the country, Planned Parenthood centers help women learn about birth control options, take care of help problems, and also provide abortions.

The birth-control movement got an unexpected boost during World War I, when hundreds of soldiers got sick with syphilis or gonorrhea while in Europe. The army tried to teach soldiers how to avoid these sexually transmitted diseases, but their lessons focused on abstinence, and it didn’t make much of a difference. Unlike in America, soldiers could buy rubber condoms easily in drugstores in Europe, and this started to limit the spread of STDs. When they came back home after the war, these men wanted to keep using condoms for birth control.

The army’s fight against STDs was a big turning point for the birth control movement. It was the first time the government had started a long-term, public discussion about something related to sex. Also, it changed birth control from a discussion of what was morally right or wrong, to a question of public health.

Although Sanger and supporters of birth control didn’t get rid of the Comstock Laws in the early-1900s, their work got things started and made it possible for women’s rights groups in the 1960s and 1970s to make birth control, especially birth control pills, a legal and normal part of American life.

MULLER V. OREGON

In 1909, the Supreme Court decided an important case about working women. The state of Oregon had passed a law limiting the number of hours women were allowed to work outside the home. Legislators at the time thought that women needed to be protected, especially women who were at an age where they might be having and raising young children. Curt Muller, the owner of a laundry business, was put on trial for violating the Oregon law. He had made one of his female employees work more than ten hours in a day.

In the case Muller v. Oregon, the Supreme Court found that Oregon’s limit on the working hours of women was constitutional because, the Court said, the government had a good reason to protect women who might be raising children.

The main question of the Muller case was if women were equal to men when it came to deciding how much they wanted to work. The Oregon law was not meant to hurt women, but in the thinking at the time, to protect them, even though it made the law unequal since there were no restrictions on how many hours men were allowed to work.

The case included a few quotes that help us understand the way people in the Gilded Age thought about gender roles. The court wrote, “woman has always been dependent upon man,” and “in the struggle for subsistence she is not an equal competitor with her brother.” And, perhaps most of all, the case showed that Americans still thought that the most important thing women could do was to have and raise children.

The case divided feminists at the time. Some thought the law did protect women and they supported it, but others thought that any law that treated women differently from men was a bad idea. Since the Muller case, new laws have gotten rid of the restrictions on working hours for women, but women are still not guaranteed equality under the Constitution.

SUFFRAGE

Women’s suffrage, or the right of women to vote in the United States, happened little by little over many years. At first, some states gave women the right to vote, and finally in 1920, the Constitution was changed to give women everywhere in the country the right to vote.

Women first started organizing to ask for suffrage in the 1840s. This was one of the results of the Seneca Falls Convention, the first ever women’s rights convention.

At the end of the Civil War in 1865, women who wanted suffrage thought that their time had finally come. With the end of slavery, there was going to be a change to the Constitution to allow African Americans to vote. But many reformers at that time were afraid that linking women’s suffrage to African American suffrage would mean that too many people would reject the 15th Amendment. So, the 15th Amendment was passed, and the Civil War resulted only in suffrage for men of all races, a step in the right direction to be sure, but still, half of all Americans were still outside the political process.

Primary Source: Drawing

Primary Source: Drawing

Susan B. Anthony, one of the first advocates for women’s suffrage. Anthony was instrumental in the movement in the 1800s but passed away before the final push for the ratification of the 19th Amendment.

The first national suffrage organizations were started in 1869 after the disappointment of the 15th Amendment. Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lucy Stone were leaders of these early organizations and in 1890 they came together to start the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

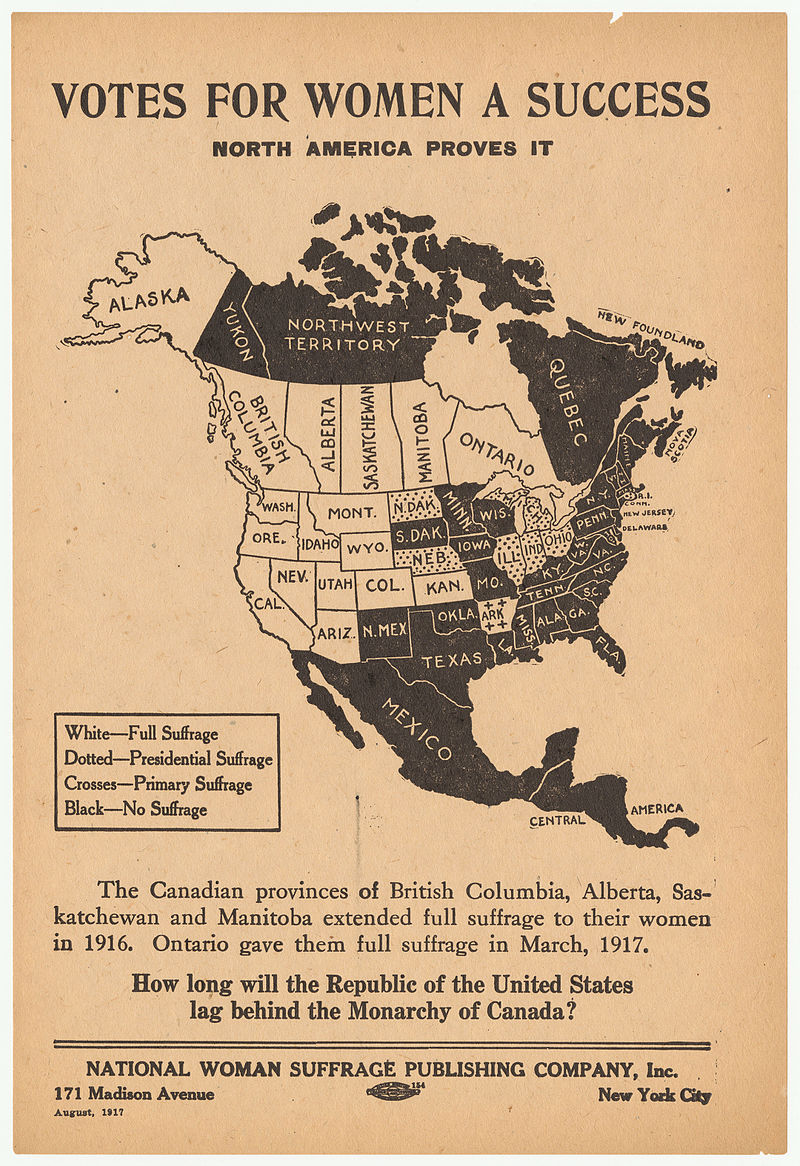

Many suffragists hoped that the Supreme Court would rule that since the Constitution guaranteed “equal protection under the law” to all Americans, women had a right to vote. So, suffragists tried to vote in the early 1870s and then filed lawsuits when they were turned away. Susan B. Anthony actually was able to vote in 1872 but was arrested. Unfortunately for the suffragists, the Supreme Court ruled against them in 1875 saying that the Constitution did not imply that women had an equal right to vote. So, the suffrage groups began the hard work of adding an amendment to the Constitution that would explicitly give women the right to vote. However, in the beginning, they mostly worked state-by-state to get each state to give women the right to vote. Primary Source: Flier

Primary Source: Flier

This map, published by the National Woman Suffrage Publishing Company shows the states that enacted laws granting women’s suffrage as of 1916. The states and Canadian provinces in white allowed full suffrage. Clearly, western states were ahead of the trend.

Progressive reformers in the beginning of the 1900s helped the suffrage movement. Many Progressives saw women’s suffrage as another Progressive goal, and they thought that if women could vote, it might help them reach some of their other goals.

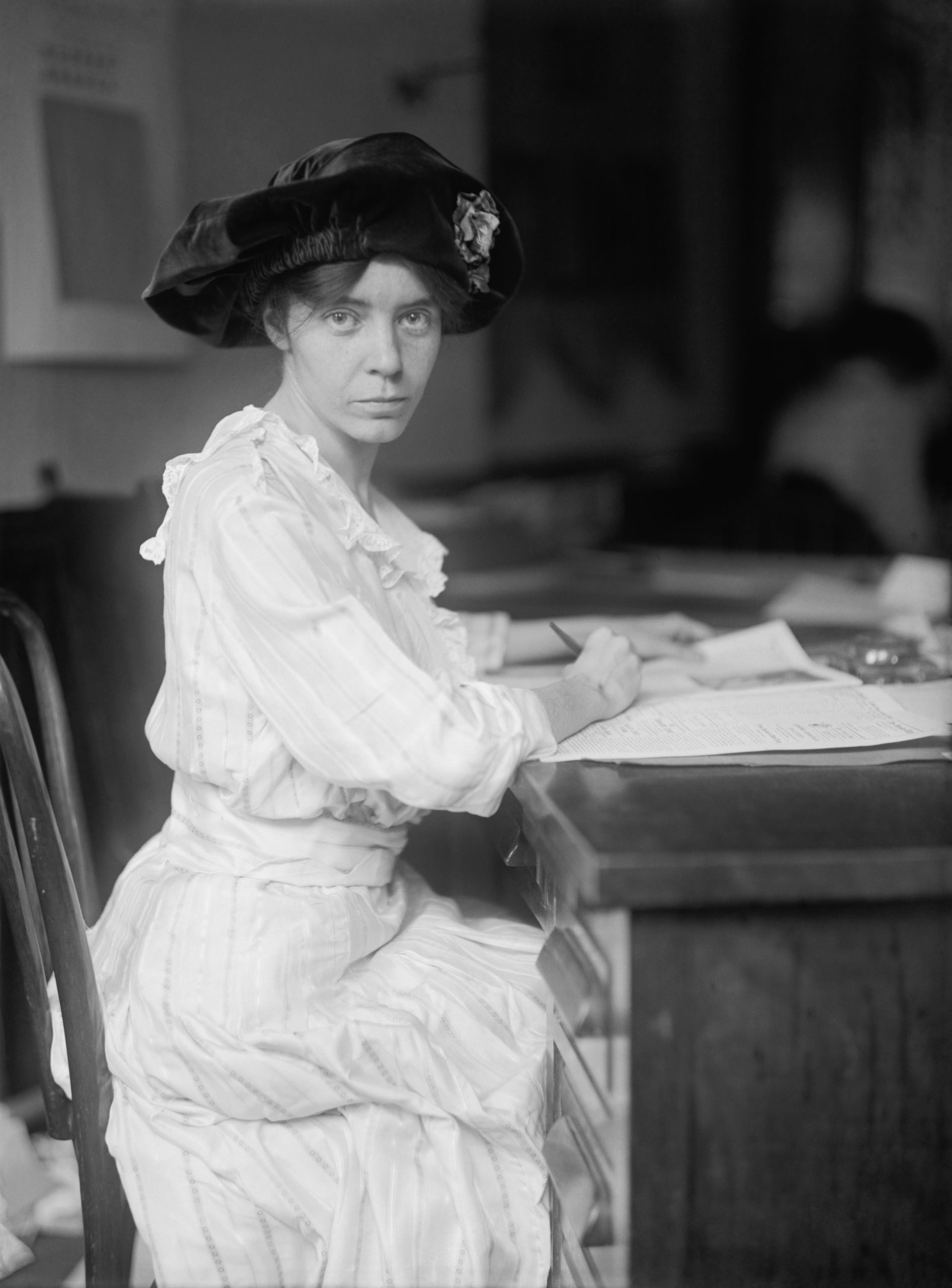

By 1916, the original organizers of the women’s suffrage organizations were gone, and a new generation of women took over. Alice Paul started the National Woman’s Party (NWP). Paul thought that women needed to show how unfair things were by taking direct action. More than 200 NWP supporters, known as the “Silent Sentinels,” were arrested in 1917 while marching at the White House. Some of the protestors went on a hunger strike and endured forced feeding after being sent to prison. The larger NAWSA that had been started in the 1800s stuck to a less dramatic strategy under the leadership of Carrie Chapman Catt but still worked hard to get an amendment to the Constitution passed.

There were many Americans who didn’t want women to vote. Brewers and distillers opposed women’s suffrage. They were afraid that women voters would vote to make alcohol illegal. Many of the New Immigrant families were used to paternalistic families in which the husband made decisions for the family about politics.

Some other businesses, such as Southern cotton mills, opposed suffrage because they were afraid that women voters would vote to end child labor. Political machines, like Tammany Hall in New York City, were afraid that the female voters would make it harder for them to keep control and stay in power.  Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Alice Paul at the time of the fight for the passage of the 19th Amendment.

At the same time Susan B. Anthony and other suffrages were starting their groups, the Women’s Anti-Suffrage Association was getting started. Known as the “antis,” they were active in 20 states. In 1911, the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage was started. They claimed to have 350,000 members. The antis said that woman suffrage, “would reduce the special protections and routes of influence available to women, destroy the family, and increase the number of socialist-leaning voters.”

Many upper-class women were against suffrage for women. They were married to or knew many powerful men and were afraid that if all women could vote, they might have less influence.

Most often the “antis” believed that politics was dirty and that women were naturally pure and should stay out of it. They worried that dividing women between political parties would hurt society overall.

Even though there were plenty of people who didn’t think women should vote, the movement for suffrage grew, especially in the West. Because states manage elections, individual states began passing laws giving women the right to vote. Many western states, which had just been settled, were just creating their suffrage laws and didn’t have a tradition of only men voting. Pioneer women who had walked the trails west and worked under the sun with their husbands, brothers, fathers and sons were in no mood to take a back seat to them when it came to politics. Eastern states, with hundreds of years of tradition, were slower to change.

Paul, Catt and the leaders of the suffragists finally got Congress to pass an amendment giving women the right to vote. And, after fighting to get enough state legislatures to ratify it, the 19th Amendment became part of the Constitution in 1920. It reads, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

When the Founding Fathers were writing the Declaration of Independence, Abigail Adams had written to her husband telling them to “remember the ladies” in their new government. Sadly, the Founding Fathers did not, and it took another 144 years and the work of thousands of women before both men and women had the right to vote.

CONCLUSION

The passage of the 19th Amendment has been rightly celebrated throughout history as an important step toward equality between men and women. In a land where the Declaration of Independence says that “all men are created equal,” it was a chance to include women in that idea.

But suffrage did not suddenly change the lives of women. It didn’t suddenly make all jobs open to women, for example. Nearly 100 years later, women are doing much more than they could before, but we still have not elected a woman president. Which leads us to our question. Could women have gotten all they did without the right to vote? Could they have opened doors of opportunity in education, health and business if the 19th Amendment had never been ratified?

What do you think? Was suffrage essential to make the lives of women better?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: Women had one of their greatest successes in 1920 when the 19th Amendment was ratified, guaranteeing them the right to vote. Women at this time had less success in their efforts to win workplace equality and access to birth control.

During the 1800s, Americans were very conservative about the roles of men and women and especially about how women could behave and dress. In the 1870s, Victoria Woodhull challenged these beliefs. She championed free love, the idea that she could love whoever she wanted and change her mind as much as she wanted. Her ideas were controversial, but she was an important early challenger to social restrictions.

Margaret Sanger believed that women couldn’t be free if they had no control over how many children they would have. She challenged the Comstock Act which prohibited the promotion of birth control. She went to jail multiple times for sending information about birth control through the mail and for opening a birth control clinic in New York City. Her organization grew and is now called Planned Parenthood. Although she wasn’t successfully able to change the law at the time, the government did become concerned about promoting reproductive health during World War I when American troops started contracting STDs. After the war, Americans continued to use condoms they had learned about while in the army.

Women suffered a legal setback in their quest for equality in the Muller v. Oregon Supreme Court Case when the Court ruled that laws that limited the number of hours women could work were constitutional. They reasoned that the primary role women played in society was to be mothers and that allowing women to work as much as they wanted might hurt society.

Women finally won the right to vote in 1920 with the passage of the 19th Amendment. Women had been working for this right since the early 1800s, but Alice Paul and Carrie Chapman Catt succeeded in convincing men in government to approve the amendment. Many western states had already granted women the right to vote in state elections.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Victoria Woodhull: Women’s rights advocate in the late 1800s. She was most famously a champion of free love.

Henry Ward Beecher: Famous preacher in the late 1800s in Brooklyn, NY. He had an affair with a married petitioner whose husband sued him. The trial was a nationally publicized public scandal. Victoria Woodhull used the case to argue for free love.

Emma Goldman: Famous socialist activist at the turn of the century. She advocated for labor and women’s rights, but lost credibility due to her connection to the Haymarket Square riot and President McKinley’s assassin.

Margaret Sanger: Champion of birth control in the early 1900s.

Planned Parenthood: Modern organization originally founded by Margaret Sanger. They provide health services and information to women, and most controversially, abortions.

Susan B. Anthony: Early champion of women’s suffrage. She headed the NAWSA. She was honored when a silver dollar coin was minted in 1979 with her likeness.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Early champion of women’s suffrage. She cofounded a group with Susan B. Anthony.

Lucy Stone: Early champion of women’s suffrage. Her organization merged with that of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Stanton’s to form the NAWSA.

National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA): Major organization working for women’s suffrage. It was led first by Susan B. Anthony and later by Carrie Chapman Catt.

Alice Paul: Advocate for women’s suffrage in the early 1900s. She founded the National Women’s Party and used more aggressive tactics to publicize the movement.

National Woman’s Party (NWP): Organization founded by Alice Paul in 1916 to work for women’s suffrage. They used more aggressive tactics to spread their message.

Carrie Chapman Catt: Leader of the NAWSA in the early 1900s. She succeeded Susan B. Anthony and saw the ratification of the 19th Amendment.

National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage: Organization in the early 1900s which fought against the passage of the 19th Amendment.

![]()

KEY IDEAS

Cult of Domesticity: Idea that men should leave home to work and earn money while women stayed at home to cook, clean and raise children. It developed in the early 1800s with the onset of the industrial revolution.

Free Love: The idea that women should be able to love whomever they want for however long they wanted, and change their mind as many times as they wanted. It was championed by Victoria Woodhull in the late 1800s.

Contraception: Any form of birth control.

Birth Control: Any form of contraception. The term was coined by Margaret Sanger.

Suffrage: The right to vote.

![]()

LOCATIONS

Brownsville Clinic: Clinic opened in Brooklyn, NY by Margaret Sanger to provide birth control. It was closed down and Sanger was arrested for violation of the Comstock Act.

![]()

LAWS & COURT CASES

Comstock Act: Law passed in 1873 the prohibited the distribution of birth control and any material promoting birth control. It was used to prosecute Margaret Sanger.

Muller v. Oregon: 1909 Supreme Court case that upheld a law limiting the number of hours women could work outside the home.

19th Amendment: Constitutional amendment ratified in 1920 granting women the right to vote.